Help via Ko-Fi

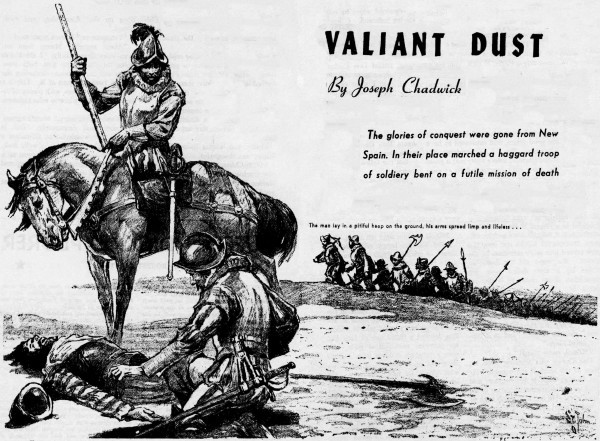

GONE now was the great show of pageantry. The banners no longer ?uttered proudly in the blazing sun of New Spain, and the armored soldiers of Charles T had lost their great air of bravado. The raw land had reached up to smite the conquistadors, and the glory of the Spanish Crown dragged in the dust. Coronado had said, "We fear not for our lives, for the arm of the true God is over us." But it seemed to every man, from mounted cavalier to lowly foot soldier, that only the dark spirit, El Diablo, traveled with them.

The advance patrol of Don Carlos de Hernandez, who was as fanatical as Coronado himself, wasted itself upon the unknown desert and, if this madness continued, was surely doomed.

"Me thinks," even Don Carlos began to say, "that this heathen devil of an India lies."

His doubt was confided only to his nephew, Don Miguel Cordova, a very young man who was fresh from Spain and upon his virgin adventure. But Don Miguel was not surprised. He too had suspicions of the native guide, a cunning fellow who talked a few words of the white man's tongue, learned from the good friars. and professed to be a Christian. But . . . a wondrous city rolled Quivira, where there was a great tree hung with countless bells of pure gold—where every native possessed dishes of the same bright metal, as well as jugs and images and all manner of ornaments? To even so young and inexperienced a man as Don Miguel, it seemed beyond belief. Yet it was Quivira that the conquistadors sought.

"Don Miguel . . ."

The cry came from an agonized throat. Don Miguel turned his gaunted mount about and saw that yet another man had fallen. The eighth in two days. Madre de Dior! thought Miguel, and felt pity in his heart. That he too might die here in this empty land seemed a certainty, yet his heart could go out to these other wretched humans.

He saw how the foot soldiers—only the two caballeros were mounted—straggled in a ragged line. They were crossbowmen, arquebusiers and swordsmen, transported across the seas and now turned into sorry creatures by the desert. No longer did the dream of riches lay in their dulled eyes. No fanaticism drove them, as it did the fierce Don Carlos. But the Indian bearers, who came last, moved steadily under their burdens and were untouched by blazing sun and scorching heat. "They are the children of this land," thought Miguel, "and so it cannot harm them."

"Miguel, come along!"

Don Carlos was shouting from his place at the head of the column. He was looking back at his nephew, and the fires of hell seemed to glitter in his black eyes. He had a hawkish beak of a nose, a cruel traplike mouth. Don Carlos was one of Coronado's most trusted captains. There was no mercy in him, no sympathy for the weak. If a man fell, he remained where he fell. Again Don Carlos bellowed, "Miguel, come along!"

But the fallen man cried out, "Have mercy—!"

Miguel was swayed. He ignored his uncle's command, risked Don Carlos' temper. He rode back and dismounted. He took the goatskin waterbag from his saddle, and he knelt—with an effort because of his armor—to give the soldier water. The goatskin was more than half empty when the man ended his greedy gulping. "Gracias, Don Miguel . . . you are a good man."

"You must get to your feet, Mateo."

"I cannot."

"I will help you, my friend. And you will ride my horse."

That was unthinkable, a mere crossbowman riding while a Castillian don walked; the soldier shook his head. "Leave me," he said, but Miguel's arms were already about him, already lifting him.

Miguel got him onto the horse, then handed him his heavy crossbow, and sheath of arrows. They went on, and a life had been saved. For how long, Miguel did not know.

THEY made night camp by a great arroyo. Tana had promised that there would be life-giving water in the creek bed, and there was none at all. The Indian was a squat man of middle age; he had a bland sort of face, but his darkeyes were full of guile. He wore a religious emblem from a chain about his neck, the gift of the friars with whom he had associated. He showed chagrin as Don Carlos, in a black temper, questioned him about their failure to find water. But it seemed to the watching young Miguel that Tana was not at all put out; it seemed that the Indian had known from the start that his promise of water would not be fulfilled.

"One day's march," Tana now said, in his bad Spanish. "We come then to the land of the humped cibolo—cattle bigger than those of the white men. And there is Quivira."

Quivira!

The name fell from the Indian's lips with a magic sound. And perhaps he believed in it. But Miguel knew, without understanding why, that there was no such wondrous city. Tana lied, whether he knew it or not, and he was leading the patrol to its death. Miguel looked at his uncle. Don Carlos had removed his flanged helmet; he sat upon a rock, a big man with pointed beard and bristling mustaches. He stared at Tana with a cruel smile, and he said. "One day's march. . . . Then it is either Quivira or I will have your tongue out!"

Miguel saw Tana's ready answering smile, and he turned away in disgust. He had lost faith; what was to have been 'a glorious adventure, a quest to add land and wealth to the Spanish Crown, had degenerated into a shabby effort of a band of men to stand off a creeping death. There was no glory, nothing but greed motivated Don Carlos . . . for Miguel knew that his uncle was impoverished and was seeking to find riches for himself—so that he might retire comfortably to Spain—rather than to raise the banner of Spain over a fabulous city. Greed was Don Carlos' fanaticism, his madness.

The campfires glowed red, pushed back the eerie desert night. The Spaniards hunkered down, munching their half-rotted food and sipping their wine—when what they really needed was a bellyful of water. They talked in low, uneasy voices; they stayed close to the brush fires, like children afraid of the dark. The Indian bearers, actually slaves, kept apart from the white men and talked among themselves in their unintelligible tongue. Miguel went beyond the camp and peered into the darkness, almost as though hoping to see something of what the Indian guide promised—a fine city, wells full of crystal clear water, the great humped cattle, gold that did not need to be mined. . . . He believed none of it. but in his heart he still faintly hoped.

He stepped by a growth of jagged cactus, heard a rattling sound. and drew his sword while his heart for an instant stood still. A creature slithered toward him; a snake struck at his leg, fangs against the steel greave protecting the leg. Miguel struck down with the sword, then withdrew back to the camp. He was a man greatly shaken.

A DARK figure loomed, a man coming to meet Miguel. It was Mateo, the crossbowman, now somewhat recovered from his weakness of mid-day.

"Something is wrong, Don Miguel?"

Miguel saw that the soldier had his crossbow loaded and ready. He said, "Nothing Mateo. Nothing but a snake."

Mateo shuddered. "This land is lost to the devil," he whispered. "Only hell could be so bad. The men are say-in. . . ."

"Saying what, friend?"

Mateo hesitated, as though afraid his words would bring him trouble. But then: "They are saying that the Indian is leading us deeper and deeper across this barrens, so that we will die terribly. They say he hates all men whose faces are white. And Don Carlos—"

"They are saying Don Carlos is mad?" Miguel prompted as the soldier broke off. "It may well be . . . I will talk again to my uncle."

He walked through the camp and found Don Carlos still perched upon the boulder, like a man enthroned, but now wrapped in his once proud but now shabby cassock. One thing about Don Carlos, Miguel realized, was his courage. He had the heart of a lion, and he feared nothing on earth. He was proud and arrogant, and he would go on even though he lost every man of the patrol.

A lanky, hatchet-faced soldier sat cross-legged on the ground before the don. He was the patrol's scribe, and in the glow of a fire he was writing upon parchment with a quill dipped in ink. Don Carlos was dictating in a low voice, and finally he said, "Now I will make my mark and affix my seal."

Quill and parchment were handed to Don Carlos, and he made his mark. The scribe heated wax, dabbed some upon the parchment, and Don Carlos pressed his signet ring upon the seal. He looked up at Miguel with a friendly smile that was a rare thing.

"I am making ready for the event of my death, my nephew," he said. He rolled the parchment and handed it to Miguel. "Should I not live out this adventure, then you shall inherit the de Hernandez estate in Spain." He lifted his hand as though to halt any protest Miguel might utter. "No; it must be so. You and I, Miguel, are all the remain of our family. It is good that my property should go to you."

"I am overwhelmed," said Miguel, yet he knew that all that remained to Don Carlos' estate was a farm of little worth. "But what if I do not live, uncle?"

"You should make some disposal of the rich lands you inherited from your father, Miguel," said Don Carlos. "You might have made such a document as this one I have given you—in my name. Although, you are young and strong and will surely live to see Spain again . . ." He looked at Miguel with his bright eyes oddly veiled. "But it is a matter for you to decide."

Miguel nodded. He saw that there was wisdom in his uncle. It would be a good thing to make sure that the Cordova estate did not pass out of the family in the event that he, Don Miguel, lost his life. He feared Don Carlos, yet he respected him. And who could say that blood was not a strong tie? Miguel said, "I will sign such a document, Don Carlos," and so had the scribe write out the testament. Unlike his uncle, Miguel had learned to read and write. He signed the parchment with a steady hand, then gave it to Don Carlos.

"But we must not die here," he said. "I ask you, my uncle, to turn back before it is too late."

The friendliness went out of the older man's manner, and now his face darkened with quick rage. "I ask no sniveling boy for advice," he all but shouted.

And Miguel then knew for a certainty that Don Carlos had no real doubts about the existence of a golden city called Quivira.

THAT night Miguel nearly died. He awoke and was suffocating. Some heavy cloth had been thrown over his face; it was his own velvet cassock. The cassock was held in place, to smother his breath and his voice, by strong hands that were also closed hard about his throat. Terror gripped his mind, and for an instant he could not fight back. Blackness seeped into his brain. His lungs seemed ready to burst for want of air. But then he managed to get a dagger from its sheath and into his hand. He raised the weapon and struck blindly. The blade struck against his assailant's breastplate, and slid off. He thrust again and again, trying to strike flesh. He was squirming, fighting, now with a wildness. Then the throttling hands left his throat. The weight of his attacker was lifted from his weakening body.

Miguel lay gasping, still feebly striking out with the dagger. But his attacker was gone, and he was safe . . . at the very moment when he would have lost consciousness. He was too shaken in his mind to throw the smothering cassock from his face, but now that the choking pressure was gone he could get enough air even through the heavy cloth. His throat ached, was swollen thick, and there was a numbness all through him.

Finally some of the weakness left him. He flung aside the cassock. He sucked in great gulps of air. He saw the night sky, the stars. He pushed himself up on his elbows and looked about. The camp seemed asleep in its entirety. No lurking figure moved about in flight. Men lay sprawled, unmoving. Miguel looked toward where Don Carlos slept . . . His uncle lay nearest him, not more than ten paces off; but Miguel could hear the rattly snore of Don Carlos' breathing, and it seemed that he must be asleep. Yet someone had tried to murder him; Miguel had only to feel of his throat to know that it had not been a mere nightmare.

He rose, reaching for his waterbag. He drank and his mind seemed to clear. He stood thinking, knowing . . . It had been Don Carlos. The soldiers had nothing against him, so they had no reason to want him dead. But that document he had signed and given to Don Carlos! It was reason enough for murder, to a greed-mad man. Despair, if not hatred, filled the heart of Miguel. He moved toward his uncle, the dagger still in his hand. He stood over Don Carlos, a wild desire to kill in him—- a urgent need to get back that document gripping him.

But Miguel hesitated. He could not kill Don Carlos!

He shuddered and went back to his bed-place, but he did not close his eyes in sleep during the remainder of the night.

THE sun climbed into the brassy sky. Against the desert's distant rim, a heat haze shimmered in constant waves. The pathetic column moved on, heading northward once more, driven by Don Carlos' mocking voice. The morning ration of water had been parcelled out; so much for Don Carlos, a little less to Don Miguel Cordova, a smaller amount to each foot soldier, and even less to the Indians. Tana, the fool, had taken his in an earthenware bowl and then had deliberately spilled it to the dust. He had grinned wolfishly at the watching white men, had mocked them. "Agua," he had said. "Water—end of day's march."

Miguel thought of that as he rode along behind Don Carlos. It had been a crazy thing, throwing away water that was worth all the gold that was supposed to be at Quivira. Or was it crazy? wondered Miguel. It might be that Tana was merely baiting the Spaniards on.

Miguel's horse was dying under him. Miguel himself was in bad shape, perhaps out of the fear forced upon him by last night's attempt upon his life. His throat still hurt, proof enough of how close a call it had been. He watched his uncle, sought guilt in the man, but Don Carlos was not a person to reveal his hidden thoughts. Even now, Don Carlos said, "Miguel, you are silent this day? Has the desert sickness gotten you?"

They rode side by side, the failing horses slowed to an uncertain walk. Miguel said, "I was nearly murdered in my sleep in the night."

"Murdered?" said Don Carlos, and swore a round oath. "My nephew set upon by a murderer? Who was the blackguard? Name him, Miguel, and I will cut his heart out!"

Miguel had hoped to startle the older man into some sign of guilt. But Don Carlos was a fox as well as a lion, and. as Miguel made no answer, he said, "One of the natives, I swear!"

Miguel's horse stopped, quivering in every muscle. Its eyes had a wild look. Miguel dismounted, and none too soon. The animal collapsed, a victim of its thirst. Miguel removed the waterbag from the saddle, and there was nothing more to salvage. He looked up and found Don Carlos watching him with a thin smile. "Ah, well," said the older man, "you are young and strong."

Tana too had stopped to watch. His eyes were malignant.

Miguel learned the agony of being afoot on the endless desert. He removed the steel greaves from his legs, threw them away . . . and later relieved himself of the weight of his breastplate. His helmet be retained as protection against the sun; he kept too his sword and his dagger, for a soldier must not abandon his arms.

The sun climbed overhead, began the descent westward. The partol lost two more of its men; they fell and the scant portion of water that could be afforded them was no help at all. The survivors complained with despairing mutters, but Don Carlos was too much their master for mutiny to ?are. The madness continued, and now there seemed no escape at all. To turn back meant death, for now even that chance was gone.

THE sun arced downward, a fiery red ball at the desert's rim. Don Carlos called a halt. He was by some miracle still mounted, and the man showed little strain. But then Don Carlos had had the lion's share of the precious water. He called up two of the arquebusiers and ordered them to lay down their firearms. He pointed to Tana.

"Seize the heathen," he ordered.

The Indian guide was roughly seized, and Don Carlos said, "Stake him out."

The order was quickly obeyed, and the Indian soon lay spread-eagled and helpless on the ground. A fire of brush was built up, a knife blade heated to a glowing red. Dismounted now, Don Carlos received the blade and walked to the Indian. This was a game a conquistador really understood!

"A liar and a fool are one," said Don Carlos. "Heathen, you will talk. You will tell us how to reach Quivira!"

"Mañana," said Tana.

"No, not tomorrow, heathen. Now—"

Miguel had to turn away. He heard the Indian's wild scream. His nostrils caught the odor of burning flesh. He was sickened, and his whole nature revolted. It went on and on until Miguel could stand no more. He swung around, shouting, "Enough, Don Carlos. I, for one, can stand no more!"

Don Carlos looked up. "Ah? You cross me, nephew?"

"You are the fool!" Miguel said wildly. "You should know there is no place like this Quivira. This Indian for some secret reason hates us Spaniards—perhaps for some wrong done him or his people. He has lied, but he is no fool. He has baited us into this devil's den, and now we are lost—just as he wanted. But I will have no more of this madness!"

"Mutiny!" said Don Carlos, rising.

He flung away the torture knife. He was smiling with some evil thought, as though this was a thing he found to his liking. And to Miguel it was suddenly very clear; Don Carlos had failed to murder him in the night, but now he had his victim in an even better trap. Don Carlos would never find the golden city of Quivira, but he was hoping to escape from the desert—to return to Spain and claim for himself the rich Cordova estate. He would have Miguel die, here, now. It was a thought alive in the glittering black eyes.

"Seize this mutineer," ordered Don Carlos.

The haggard, dull-eyed soldiers stared and were unmoving. A kindness occasionally given now repaid Don Miguel Cordova. Don Carlos saw that here was more mutiny, and he swore with a great blasphemy. He drew his great sword with a flourish.

"Be my witnesses," he said. "I punish a mutineer!"

He lunged at Miguel, whose armor had that day been discarded. Miguel dodged the first deadly blow, then drew his own sword. The naked blades glinted dully in the fading light. The two men fought with savage strokes, with lightning thrusts. Don Carlos drew first blood, a stab to Miguel's left arm. The soldiers made way for them. The Indian stared with dull fascination. The tortured Tana forgot his own pain to strain in his bounds and watch. Miguel's blade glanced off Don Carlos' armor. He was beaten back and back. But he could move more quickly. And now he swung a great stroke. The blades clashed, and Don Carlos' weapon was knocked from his hand. Miguel held his point to his uncle's throat.

"I SHOULD kill you," he said, gasping for breath. "But I let you live because you are of my own blood. You will harken, Don Carlos—I am taking command. We shall forget Quivira, and try to find our way out of this death trap. Mutiny? Well enough. I shall stand before Coronado, if we live."

He turned from Don Carlos, and had his slight arm wound bandaged by one of the soldiers. Then he went to Tana. "Mateo," he ordered, "release this poor devil."

He could see that the Indian was dying. Don Carlos' torture had not loosened a tongue but it had taken a life. A sip of water was given to Tana, and then he talked to the Indian bearers. He talked long, and the others nodded. Finally Tana turned his dulling eyes toward Miguel.

"It is good to find one a man with a clean heart among the Spaniards," he said in his awkward Spanish. His voice was weak, a mere whisper. "I have told my people to take you out of the desert, amigo. Water is not so far. You will be safe—" A shudder swept over him. Then: "There is no Quivira. . . ."

Miguel rose from kneeling beside the dying Indian. Then he heard the soldier Mateo cry out some warning. He turned and saw Don Carlos lunging at him, almost on him, a dagger striking down. Fear clutched at Miguel. He tried to jump backward, but he tripped and fell. Don Carlos bent over him, his black eyes full of a look of triumph. But the knife blade missed Miguel's throat by a scant margin. A crossbow had twanged. An arrow drove through the neck of Don Carlos. The don fell. He died hard. . . .

THE sun was gone. A purplish haze lay over the desert. The Indian bearers were already setting out, to lead the way to water as Tana had ordered them. Two shallow graves had been opened, and were now filled in. Rocks were gathered. A cairn was raised. The small, pathetic band of conquistadors stood by the burying-place. The crossbowman, Mateo, was pale and shaken. He had killed a Spanish don, one of Coronado's captains, and that meant punishment.

Miguel read Mateo's unspoken fears. He stooped and picked the arrow which had been withdrawn from the dead man's neck. He snapped it in two across his knee. He threw the broken pieces to the dust.

"Don Carlos de Hernandez died," he said, "of the desert sickness."

He turned and walked after the Indians, followed by his sorry band. And what would tell, if men did not, the secrets of the trail to Quivira?

THE END