Help via Ko-Fi

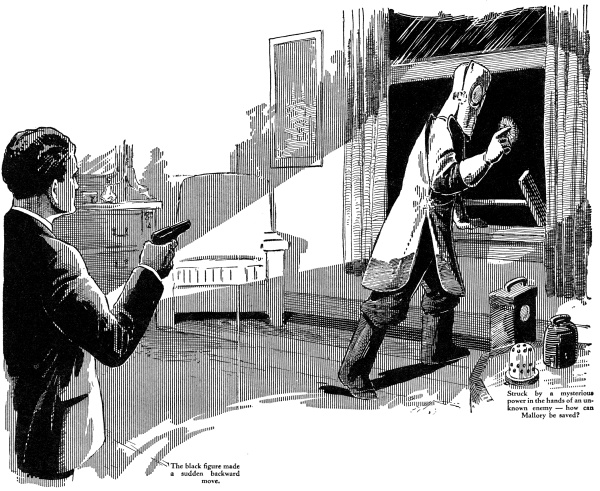

Science clashes with science in this swiftly moving tale, crowded with breathless action. Try to identify the man in the black mask!

WHEN will the world realize that guns and bombs as weapons of murder are being superseded by instruments twice as deadly, and ten times as difficult to defend oneself against?

We read in the daily press, that scientists have proved the theory of atomic destruction of matter. Yet only a few years ago, science teachers taught us that matter was indestructible. Do we realize that each new accomplishment of science, besides helping mankind, also gives the educated criminal a new armory to war against unprotected civilization? And that, in order to combat these new perils, science must come to the aid of the detective, guiding and assisting him in the detection of crime, and the conviction o the criminal?

Radium, for instance! A boon to the sick, yet at the same time, a terrible menace in the hands of an evildoer. In this story Mr. Curry, who is a writer too well known to need introduction to our readers, develops an extraordinary plot, full of sound, practical and every-day science.

RAYS OF DEATH

By Tom Curry

CHAPTER I

Lawson Is Called Back

DETECTIVE MORAN'S steel-grey eyes looked straight ahead as he climbed the flight of stairs which led to the lighted door. Various odors, strange to him and lumped by the detective under the descriptive name of "stinks", reached his nostrils. He squared his broad shoulders and took the derby from his bullet head, displaying short-clipped brown hair.

"Lawson!" he called.

"Here! Is that you, Moran?"

Young Lawson, a research chemist who had formerly been a member of the police organization, but was now working for a private company, held out a hand stained yellow and brown by chemicals and sat his visitor down in a nearby chair.

"Gosh, Lawson!" exclaimed the detective. "We surely miss you. Too bad the red tape put you out."

It was red tape alone which had caused the department to oust Lawson. The great chemist had been working at a small salary, but with unlimited facilities, in his own laboratory in police headquarters. But, since he had no regular duties but simply came and Went as he pleased, the ire of some hard-boiled official was aroused, and he had been discharged. The work of the department was done by city chemists and doctors; liquor analyses, forensic medicine and bacteriology being outside of the realm of the common detective. The inspector who had brought the valuable Lawson into the organization, and allowed him free run of the city's facilities, had been reprimanded.

Moran admired the quality of Lawson's mind too much to allow the chemist to drop out of his busy life. He visited Lawson whenever possible and, though the chemist was often irritable and refused to be disturbed while he was working, Moran did not take it amiss. He knew Lawson liked him.

The scientist was pale, with an acid scar under his right eye; a slender man, with delicate, long fingers and light blue eyes. His head was large, and his brown hair in a state of perpetual disorder.

"I've come on business," said Moran delicately: "I know we have no call on you any more, Lawson—it was a dirty trick to let you out that way—but I thought, if you weren't too busy—"

Moran stopped, evidently embarrassed. Lawson laughed: "Go on, Moran! You know I don't care about that. I had a good time while I was with you and enjoyed the work we did together. While I wouldn't care to be bothered here by most of your colleagues—I'm too busy for that-you're welcome to come and take a chance any time if I can be of assistance and can spare the time."

"Yes, I thought you'd feel that way. I'm out of my depth now, and I hate to admit it to the chief. You know, when you were helping me, I solved two or three chemical cases. That's why they put me on this one."

"What's happened, then? A poisoning?"

The detective's brow corrugated in thick lines:

"No. It might almost be an accident. I've been out there all day. Was put on special detail. The local police are working on it, but headquarters sent me to see what I could do. Have you ever heard of radium?"

Lawson laughed: "I should say so!"

"I mean, do you know much about it? Is it inflammable?"

"Scarcely that. It burns itself up. The chemistry of the radium elements is magnificent, Moran. You see, the metal is decomposing itself, but the action cannot be hurried or retarded. Radium salts—the metal itself is scarcely known—give off three rays: the alpha ray, which consists of positively charged helium1—that's used in dirigibles now instead of hydrogen; the beta rays, negatively-charged electrons or units of electricity; and the gamma rays, which are very similar to X-rays. The alpha rays will illuminate a zinc-sulphide screen—which is how we make our luminous watch and clock dials. In 1898—"

1: Helium is one of the elements first discovered in other planets or stars. As early as 1868, the presence and existence of helium was discovered in the sun by spectroscopic examination of the suns light. It is to this fact it owes its name; helios being the Greek word meaning sun. Its atomic weight is 4.0, as compared to hydrogens 1.008: but its lower efficiency as a for dirigibles is offset by non-inflammableness. It was finally isolated by Ramsey in 1895.

"Cut it out!" begged Moran, mopping his brow: "I'll talk and you can figure it out in your own head. Do you read the papers?"

A Curious Explosion

LAWSON shook his head: "Not every day. I've been up here now for three days and haven't been out. My food is brought in to me and I take a nap on the couch once in a while. Why?"

"Because you must have seen the account of the terrific explosion. The Malloradium Company's plant blew up like a leaky still at two A. M. Monday night, and the whole building was demolished. Luckily, the plant stands off by itself in a large field, or there would have been a lot more damage done. The fire has been extinguished after a hard fight. Two watchmen inside were killed, and two who were patrolling the grounds were knocked for a goal. They're able to talk now, and I had a word with them. Do you know what they say?"

"No. Moran, you seem excited?"

"Sure I am. The watchmen say they couldn't see well Monday night because of the fog!" Lawson, smoking a cigaret, watched his friend's face. Moran half smiled, half frowned: "Listen, Lawson. There was no fog on Monday night! It was clear, moonlight, stars shining as pretty as could be. Everybody in the neighborhood says the same thing."

"Maybe the watchmen were raving."

"No. They both claim the same thing. Whoever blew up the plant—and no doubt it was blown up—got in under cover of the fog and entered the building. The two watchmen inside were taken care of, bound and left to be blown to hell. We found some parts of the poor fellows."

"But where does the radium come in?"

"I'll tell you something about the company. There's a man named William Keating out there, almost crazy, picking over the ruins. He thinks the explosion might have been accidental, spontaneous combustion or something like that, and that his precious radium may be lying in there somewhere. There was an ounce of the stuff in the company's safe, in the basement. Well, this Keating has been trying to dig out the safe and has got burned and made himself a nuisance to the firemen. The owner of the works, Byfield Mallory, has been out there, too, raging around. D' you know how much he says that little bit of white powder is worth?"

"About two million dollars," said Lawson, after' a rapid calculation: "Radium's selling at $70,000 a gram—or was, the last time I heard. But I thought the Belge concern had a monopoly on the stuff? Didn't know the Americans were making any just now."

"I couldn't tell you about that. But two million dollars for a few pinches of stuff seems like a Chinaman's dream to me. Could it be true?"

"Surely. It takes some nine hundred processes to get a few milligrams of radium out of several tons of uranium ore, either pitchblende or carnotite. Pitchblende is found in Europe, the carnotite found in the American West."

Moran held up his hands: "You can see how I feel. Keating and Mallory are just about crazy, and I can't get much out of them. Keating won't believe the radium actually is stolen. He keeps saying no one could sell it without being caught."

"That's true. Anybody who turned up with an ounce of radium would be investigated at once. Only hospitals, research laboratories and, perhaps, a few factories which manufacture such things as airplane struts or luminous dials could have any use for radium. Doctors usually borrow it from radium banks."

"Well—I hate to quit on this case. It would be a feather in my cap if I could find that radium. I've got men searching the ruins now; but the fog the watchmen mention made me wonder if there wasn't something more to it than there seems to be. By the way—the experts claim that the explosion looks like T.N.T. had been used."

"Trinitrotoluol?2 Possibly. Now, I'm working on something, but am at a phase where I can leave it for a few days. I'll meet you here tomorrow morning, and we'll go out and take a look. Where's the factory—-or what's left of it?"

2: Trinitotoluol (or toluene). A high explosive made by treating toluene with nitric acid—thus forming the chemical compound CH3C6H2 (NO2)3. This substance, generally referred to as T.N.T., is used for filling high explosive shells: for it melts readily (at 81.5° Centigrade) and can be poured from one vessel to another rapidly and in safety.

"Out in Queens. As I told you, Mallory owns a tract of flat land out there, and it was there the radium plant was built."

"All right, then. I'll see you tomorrow. S'long."

Moran took his leave, to go home and snatch a few hours sleep. Hope was in his heart, hope that he might be the one to solve the case. He had been assigned to it on special detail, and wished to keep his reputation clear as a solver of chemical mysteries. In this, Lawson was his chief aid. Moran would place the facilities of the great organization at the chemist's call, and Lawson would direct the inquiry through the detective.

CHAPTER II

$2,000,000.00 GONE

THE spring sun shone brightly, as Detective Moran, escorting his friend Lawson, stepped up to the wire gate of what had been the Malloradium Company's plant. A railroad switch ran in from the nearby main line; and two or three cars, which had come from the West with the carnotite ore from which the radium was extracted, were lying as they had fallen from the force of the explosion.

Piles of brick, plaster, and burned material, vats, furnaces and broken glassware were strewn about in profusion. The amount of labor necessary to obtain the radium was so immense, and the chemicals so numerous, that it was actually cheaper to transport the heavy ore from the West than to take the chemicals to the uranium deposits. To produce a single gram of radium bromide, five hundred tons of ore had to be treated with some five hundred tons of chemicals and a Niagara of distilled water.

Moran was admitted at once, Lawson trailing after him. Firemen and police stood about; and inside the inclosure were several cars, among them a black limousine.

"That car belongs to Mallory, the owner," said Moran, indicating the limousine: "There he is, himself, over by those tubs. That's Keating with him, the smaller fellow."

Lawson looked at them. Mallory, the owner of the demolished factory, was a huge, bluff man, with iron-gray hair and a red face. The chemist, watching him, could see the temper which Mallory was venting on his manager. Keating, black of hair, was of slighter build; just now he wore a worried look.

The detective and his friend made their way past the cars towards the group by the ruins. As Lawson, picking his way among the bits of brick and wood which had been placed there by the terrible hand of the explosion, passed the limousine, he glanced up.

The chauffeur was on the seat, but Lawson did not look at the driver. He caught sight of the white face of a girl who was staring at the ruins.

She was beautiful. Her face, though pale, was exquisite in appearance, and her great dark eyes lighted her countenance. She was slight of figure, but clothed with a simplicity which was elegant. Lawson, whose heart had began to leap, stopped beside the car. He saw dark curls under her small hat.

For a moment, the chemist, usually so businesslike, stared at the girl with what might have been rudeness, had it not been for the honest admiration in his gaze.

Moran had gone on. He was talking, thinking Lawson was still at his side. The girl, seeing the detective speaking to empty air, looked round and caught sight of the chemist, struck dumb by her beauty. For a moment, a surprised little smile appeared on her red lips; then she flushed and turned away.

The detective discovered Lawson's absence, and turned to see where the chemist was. But Lawson was already running after him.

They stopped for a few: moments at the edge of the ruins.

"Some job, eh?" said Moran, almost proudly. Keating, the manager, perceiving Moran, hurried over to him.

"Mr. Mallory's here," he said: "I've been hoping against hope to find the radium in the vault. But the vault has been smashed, too. The men have just reached it. Thirty grams of it-imagine! Worth over two million dollars."

Moran strode over to where the big bluff owner of the works stood frowning at the debris. Mallory gave the detective but a short nod, and then turned on Keating, as the manager returned to his side. Lawson was at his heels.

"What about the bank at the new hospital, eh?" roared Mallory. "Where's my $100,000 guarantee that I'll have the stuff delivered, purified, ready for use, next Wednesday?"

"Mr. Mallory, it must be in there somewhere! The safe is on its face; it looks smashed, but once we get it turned over, we may find the radium. I've sent for more tools. Let's hope it's there."

"And suppose it isn't?" growled Mallory: "What a fool you are, Keating! You may be a good chemist, but you're a rotten executive."

Keating hung his head: "If the worse comes to the worst, sir," he said, "we can get ten grams of radium chloride, enough to fill the hospital order, from Dr. Leopold of the Belge Company. He has been in touch with us before. You remember he sold us five grams two years ago. He'll let us have a commission, I'm sure."

"Curse it," exploded Mallory, unappeased: "Some carelessness of yours has caused this."

Keating shook his head despairingly. "I'm sure we'll find it in there somewhere," he said: "Who would steal radium? It could not be marketed. It would be useless to anyone."

But Mallory only grew angrier and angrier. The ruthlessness of the big man was evident in his face, the ruthlessness which had brought him from the ranks of life to the top.

Byfield Mallory was a mineralogist by training, but a roving disposition in his youth had kept him moving. He had prospected for some time, in the Bad Lands of the West. With a man named James Tholl, who had perished in the desert, he had discovered carnotite ores of high radium content, and he had fought tooth and nail against anyone who had tried to interfere with him. He had left all behind; and now, some twenty years later, he was owner of his own company and his own ore deposits.

The big man paid no attention to Moran and Lawson, after the contemptuous short nod to the detective. He stormed at Keating; and at last his anger grew out of bounds, and he shook his fist in the frightened manager's face.

Then Lawson, watching the rage of the man, heard a soft voice at his elbow.

"Father!"

It was the girl who had been in the car. She gave Lawson a fleeting glance. And then, veiling her dark eyes with those long lashes, she stepped past the chemist and Moran and placed her hand on her father's arm.

"Yes, Edith. Just a minute."

"Don't lose your temper, father. Mr. Keating is not to blame, I'm sure. If the radium's in the ruins, he'll get it out."

"He's a fool," growled Mallory.

But his daughter pulled at his sleeve, until the big fellow! turned and accompanied her to the limousine. The motor was started, and they were driven away. Lawson, looking after her, saw Edith's face framed in the rear window for a moment, before she turned back to the task of placating her father.

CHAPTER III

The Mysterious Fog

"WHEW!"

Keating turned to Moran: "What a hell of a temper the boss has!"

"You said it," replied the detective: "Why don't you slam him one on the kisser?"

Keating smiled, as though he might have enjoyed doing so; but then, he froze suddenly, and the worried look reappeared on his face. A workman was coming towards him.

"Well?" asked Keating eagerly.

"Got it turned over, Mr. Keating."

The manager shot away in a flash. Moran and Lawson followed to the edge of the ruins, and climbed over the foundations. The smell of chemicals was very strong.

Keating, in the midst of a group of workmen, was rummaging in the debris. Lawson and Moran picked their way towards him.

They were in the hole which had once been the basement of the factory. The workmen had unearthed the safe which had been used as a storage space for the radium-worth a fabulous sum and yet of such small amount that a man could hold it in the palm of his hand. But one would not hold it in the hand, by any means, if he valued his skin.

"It'll be in a round lead box," Keating was crying to the men: "Look, damn you, look! It may be anywhere around here. It's not in the safe."

The doors of the safe had been blown off and, though there were many papers and various things of value within the twisted steel box, still Keating did not find what he was after. The radium was gone.

"Somebody blew hell out of it, before they let the factory have it," said Moran, looking at the safe with an expert eye.

"If it was burglars," said Lawson, "they'll be damn sorry if they carry that radium around! It'll burn them to bits. Unless expert chemists did it."

"They couldn't sell it, I tell you," cried Keating frantically: "It would be worthless to anyone l" Lawson was silenced.

"What about this phoney fog?" asked Moran: "There was no fog that night, but the watchmen say fog kept them from seeing who came in and blew up the works. They heard a dull explosion inside, they say, and started to the factory to investigate it. They were on the outskirts of the ground, patrolling. Luckily, for them, before they got too near, the whole business went up. The burglars must have planted their T.N.T. and then blown the safe. When they got the radium, if that was what they were after, they slipped out under cover of the so-called mist, and set off the big charge by battery, blowing everything to hell."

But Keating was too perturbed to take in much of the detective's explanation.

"I've got to go and tell him I can't find the stuff. It must have been stolen—but I can hardly believe common burglars would take radium, unless through ignorance, of course. He'll be angry. But I'll have to go and tell him I can't find it."

"We'll go with you," said Lawson suddenly. Moran nodded. The two followed the manager to his car, and were soon driving out into Long Island, where the mansion of Mallory, the Radium King, stood on his great estate.

The Radium King

THE Mallory place consisted of some thirty acres of landscaped grounds. The mansion was of stone, low and massive, surrounded by large trees and fence hedge. Winding gravel drives and paths, running off in every direction from the house, were well kept. The main entrance was through an iron gate where stood the lodge of the gate-keeper, and led under an archway of huge elms. The grounds touched the Sound at their northern extremity.

Moran was somewhat struck by the richness of all this. Keating had seen it before and it had become commonplace to him. What he worried about was, not so much the house, but the man inside it. "He'll be very angry," he kept saying nervously; until Moran growled something about "Telling him to go to hell!"

"Is Mrs. Mallory alive?" asked Lawson, as the manager of the Malloradium Company swung his car around the vast circle before the porte cochère.

"No. The boss is a widower. His wife died eight years ago. Miss Edith keeps house and has charge of the servants. And she knows her business, too. The household is well run. Nobody else except the servants—there's ten of them—lives here. None of Mallory's relations can stand him, he's got too hard a temper. But the girl knows how to manage him. He's not so bad in a way—though he could be a lot better."

Keating drew his car up before the steps. He rang a bell, and a butler opened the door. Lawson and Moran followed the manager; the detective with his matter-of-fact air, though the usual look of abstraction of the chemist was strangely absent as Lawson took his seat in the great reception room.

Lawson seemed to be watching for something, or someone. Moran found it necessary to nudge him; for the chemist did not move, even after the butler returned to lead the way to the second floor.

Keating stepped inside the study—for they were being received in Mallory's apartments.

The Radium King was seated in a dark-blue armchair, his heavy head bowed on his chest, waiting like a lion in his den for his victim. He glared at the three, singling out Keating.

"Well?" growled the big fellow.

Moran twiddled his thumbs, watching keenly but failing to catch Mallory's eye. Lawson, whose abstraction had returned to him, waited.

"I must admit, Mr. Mallory, that the radium bromide seems to have been stolen. There is little doubt left in my mind, though I hate to admit it, that burglars entered the factory, cracked the safe and stole the lead box containing the radium salts.; then blew up the factory to cover their tracks. I have searched over every foot of the debris, but the container is not there. It might have melted down in the heat, of course; but some trace of it would have been found. Anyway, it is obvious that the safe was blown open."

"And what do you expect to do now, my fine manager?" gritted the radium king.

Lawson, who had a sense of humor, could scarcely restrain a smile as he saw Keating's wince of terror.

"Why, there's only one thing to do: allow Detective Moran, and the private agencies, to search for the radium."

"And do you suppose such numbskulls can find such a thing and would know it if they did?" Moran fiushed to the roots of his short-cropped hair. Lawson smiled with his eyes.

"We must be patient," said Keating, swallowing.

Mallory rose and towered over the three. "Curse it," he cried, "curse it! Two years, Keating, two years of work and investment! Fifteen thousand tons of ore, fifteen thousand tons of expensive chemicals, a hundred thousand tons of distilled water, to obtain that pinch of salt! I've mortgaged everything I've got, to beat out the Belge Company.

A Secret Process

"THE new Mallory process, my secret process which made it possible to compete with the foreign monopoly: where's it all now? Damn you! And am I to sit here and twiddle my thumbs, while a few fools look for radium burglars? How about my hundred-thousand dollar guarantee and only four days to deliver ten grams of bromide, purified, to the new Boston hospital? What are you going to do?"

The Radium King stormed up and down the room, cursing, shaking his great fists, his face red with rage.

"I've fought them all," he bellowed: "I've beaten them all; And now—this!"

A light knock sounded on the door. Lawson, nearest it, froze suddenly in an attitude of listening, to shut out the mighty curses of Mallory and hear who might be outside.

"Father!" It was the gentle but firm voice of Edith Mallory. She turned the knob, and stood there, clad in white, Lawson, looking at her expectantly, was delighted to receive a look of recognition. But then she passed him, and went to her father.

"You mustn't go off into these terrible rages," she admonished: "Sit down in your chair and talk quietly."

He obeyed, grumbling. "Fools," he muttered.

Moran stepped forward, clearing his throat. He was taking charge of the situation.

"Well, Mr. Mallory. I'd like to ask you a few questions. Sometimes we're not as stupid as we seem. If I can get some idea of the situation from you—you may be able to give me a lead to work on. First, have you any enemies?"

Mallory glared at the big detective. "Thousands," he growled at last.

Moran was nonplussed. He scratched his head. The girl's laugh tinkled and Moran flushed.

"Do you think such a man as I can go through life and make no enemies?" went on Mallory: "Do you think a man attains my present position without leaving strewn behind him those who have opposed him? Do you think wealth comes to a man because he's kind and polite and lets the other fellow trample on him?"

"No!"

It was Lawson who answered. He stepped into the breach, left by the perplexed Moran.

"Mr. Mallory," he said gravely, "what you say is quite true, but it does not assist us in our investigation. If you want Detective Moran and his organization behind you in your search, you must help us. Can you think of anyone who might have done this to revenge himself upon you? In this question, Moran is quite right. He must have some lines along which to work. As Mr. Keating says, it is highly improbable that any common burglar would steal radium. For where would he sell it?"

Lawson's air of command, and the girl's appeasing presence, calmed the Radium King.

"I had forty chemists and fifty workmen in the plant," said Mallory slowly: "Keating can tell you their names. All the American competitors are out of the field. They were forced out three years ago, as I was, when the Belge Company entered the market. The Belge Company has a practical monopoly at present, because of some high-grade pitchblende uncovered in Africa. It was only through the discovery of the new Mallory process -which is secret—that I was enabled, two years ago, to begin production once again. This process cuts out what were processes number 765 to 853, and 878 to 901. As these were extremely expensive parts of the extraction, I have been able to put radium on the market at the same price as the Belge Company, seventy thousand dollars a gram."

"Then the Belge Company would profit if by chance your supply of radium was lost?"

"Yes! Undoubtedly! But while such an act is possible, it is not probable. Dr. Felix Leopold, who represents the Belge Company in this country, does not like me personally—and I don't like him—but I don't believe he would stoop to such a thing. He is an agent, pure and simple; the Belge Company is well known throughout the world, and is an honorable concern. Besides, if they wanted to fight me, they could undersell me. In all my years of manufacture, even when I was racing tooth and nail with six other companies for supremacy, no such act has ever been perpetrated."

"Then you believe it may be an act of private revenge?"

Mallory shrugged: "How can I say? My mind has been shocked by the disaster. I can think of many who might wish me bad luck, but not one who would do such a thing. As you may have gathered, I have contracted to furnish the new Boston Hospital with ten grams of radium bromide. It is to be delivered Wednesday. I have a hundred-thousand dollar guarantee posted that it will be ready." The Radium King had little more to say. Keating, the manager, had the names of the employes of the company and these were people whom Moran might investigate.

"Shall I get ten grams of radium chloride from Leopold, then?" asked Keating, as they took their eave.

"Yes," said Mallory w'earily, closing his eyes: "Yes. You can get it in shape by Wednesday. The X-Lab will let you have a table and facilities. The other orders are farther in the future, and can wait. Perhaps the stuff will turn up. Offer $25,000 reward for the return of the radium intact."

The three left the big man then, and entered Keating's car.

CHAPTER IV

Dr. Leopold Enters the Case

"WHAT was this secret process Mr. Mallory spoke of?" asked Lawson.

"Oh," said Keating, "I meant to tell you about that! When you mentioned the fact that someone might have blown the factory up for a grudge, and we were talking it over with the boss, there came to my mind the facts of the new Mallory process. Well, one of our young research chemists, a man named Charles Sommers, invented it. He stumbled on it while working with radium salts. Mallory kept him at research work, as he did several of us, including myself. Sommers is brilliant, a great Worker. He has been under contract with Mallory for five years now.

"Here's the point: Sommers' contract called for only fifty dollars a week, as he was just out of the University and might not be of any account. He discovered this process and had to turn it over to Mallory. It became of vast importance to us. Mallory took the process, gave it his own name, and started manufacturing again. Sommers was still working for us at fifty a week. Mallory did not raise his salary or give him any reward. Sommers, naturally, must have been angry and hurt. But he has worked along with us just the same. He did not stand out in my mind as a possible—but no, you'd not think Sommers would do such a thing. He's a scientist, pure and simple, and would never become a murderer and thief. No!"

"Well—let me have his address," said Moran: "Here, when we get to where we're going, you can give me a list of your employes and I'll investigate them."

"By the way," said Lawson, "where are we going now?"

Keating was crossing the Fifty-ninth Street Bridge. "I'm going to see Leopold, of the Belge Company," he said.

"That's another bird we want to see," said Moran. "Ain't he the representative of the company that has had a monopoly on the stuff?"

"Yes. His offices are on Forty-sixth Street."

Dr. Leopold was a nervous little man, with a scraggy moustache. He spoke with a slight French accent. He smiled cordially at Keating, and acknowledged the introductions to Moran and Lawson. He held the latter's hand for a moment, and looked at him keenly.

"Not the Dr. Lawson who published such a competent treatise on 'Gold Colloids and their Behavior in Magnetic Fields'?"

Lawson nodded. Moran's eyes opened. He knew that Lawson had a name in the chemical world; but it was not often that anyone knew enough about chemistry to appreciate his work.

Keating was surprised, too. "I never connected you with that, Dr. Lawson," he said: "I suppose my mind's been off key since the calamity at the works. You heard of that, of course, Dr. Leopold?"

Leopold nodded gravely. "Come inside."

There were two or three stenographers and an office boy in the ante-room, and the doctor led the way into his own sanctum, a room filled with charts, technical books and a chemical bench in one corner, covered with apparatus and small vials of chemicals.

"I still play with chemistry," said Leopold, smiling as his visitors viewed the bench, "though I am little more now than a high-powered salesman. You know, Dr. Lawson, it is necessary to educate our limited clientele as to the uses of radium."

The four were seated. Moran took out a cigar, bit off the end, and settled himself to listen to long names which to him were so much Greek.

"Dr. Leopold," said Keating, "you have heard of the blowing up of our plant. It was done with trinitrotoluol, we believe. Two watchmen were killed. We hoped to locate our radium bromide in the safe; but when we dug it out of the ruins, we found that the safe had been blown open and the radium bromide extracted. The new Boston hospital has ordered ten grams from us. Our plant is demolished, our radium gone; we must fill our order in Boston, however, or lose one hundred thousand dollars. Now, the market for radium bromide is seventy dollars a milligram, is it not?"

Sommers Says "No!"

LEOPOLD nodded gravely: "Yes. But, if you take ten grams from us, we will let you have it at sixty-five dollars per milligram. That will be a brokerage profit of fifty thousand dollars on the ten grams."

"That is quite fair. Mr. Mallory has authorized me to deal with you."

Dr. Leopold rose. "Tell Mr. Mallory how sorry we were to hear of the disaster, will you not?" he said: "One of our executives, Mr. Stephen Tollerman, is here on a visit. He is in the next room, and I will be glad to call him. He would be pleased to meet you, Mr. Keating, and you also, Dr. Lawson. Perhaps he can help us arrange the details of the order."

Tollerman was introduced. He was a tall man, with grey-streaked hair, blue eyes and brown cheeks.

"Mr. Tollerman was one of the discoverers of the pitchblende ores in Africa," said Leopold.

"Well—how soon do you think I can have the radium?" asked Keating, after the amenities of the introductions had passed: "Is it chloride you have?"

"Yes. You know, it is easier to extract the metal in the form of chloride from pitchblende; while the bromide is naturally obtained from carnotite. At present I have no supply on hand; but I can get you as much as twenty grams within eight days. I must send to our bank in Belgium for it."

"Eight days!" cried Keating: "Why, Dr. Leopold, by Wednesday next, we must deliver ten grams to the new Boston Hospital or we lose a hundred thousand dollars! That's our guarantee which is posted to insure delivery of the radium."

Leopold looked at his colleague, Tollerman. The latter shook his head. "The metal can be rushed here by the first boat," he said: "Unfortunately, there are no airplanes to carry it. It will be Saturday next before we can get it. It is unfortunate."

"Mr. Tollerman is right," said Leopold: "Had I anticipated anything of this sort, I would have sent at once for metal, on hearing of the explosion in your plant but we were certain you would locate your radium bromide in the safe."

"But you offered us, on brokerage terms, ten grams of radium chloride not a month ago," wailed Keating: "Where is that?"

Tollerman and Leopold exchanged glances again. Then Leopold spoke.

"It has been rented, Mr. Keating. A research chemist came in and offered us five thousand dollars for the use of our ten grams of salt for two weeks. He said he was in the midst of an experiment. I rented the radium to him, and he has it now."

"What was his name? Where is he?" cried Keating.

"His name is Charles Sommers. He said he had worked for you. He came in only yesterday, and I delivered the metal to him this morning. I asked him about the explosion. He said he hoped you would find your radium bromide in the safe."

"Sommers!"

"Don't you think the Boston people would give you a few days leeway?" asked Tollerman: "We'd like to make the sale to you very much."

Keating shook his head dismally: "The man in charge up there doesn't like Mr. Mallory. He'd be only too glad to make us pay the forfeit. But I can scarcely believe Sommers could have—what did he look like?"

" "He's a personable young man," said Leopold: Of medium height, with fair hair and blue eyes."

"That's Sommers," cried Keating. "The dog!"

Telephone calls—one by Leopold to Charles Sommers, the discoverer of the secret Mallory process, and one by Keating to Mallory, who exploded over the wire—found Keating with permission to deal with the young chemist, and Sommers in Leopold's office, looking cool and collected.

"Sommers," said Keating sternly, "you have ten grams of radium chloride leased from Dr. Leopold. I ask you, for the good of the firm, to turn it back and allow us to fill our order at the new Boston Hospital, where a bank is to be established. This you knew as well as I. What a coincidence that you should come here and rent the only purchasable radium at hand l"

Keating's sarcasm did not touch Sommers. He coolly returned the manager's gaze. "I'm working on something now, in my own laboratory," he said: "To give up the radium now would throw all my experiments off."

Keating grew angry. He stormed at the chemist who had formerly taken his orders. But Sommers was obdurate, he would not give up the radium.

"We stand to lose a hundred thousand dollars," cried Keating, again and again.

At last, Sommers said: "I'll tell you what I'll do, Keating. Give me fifty thousand dollars for my trouble, and I'll deliver the radium back here, and you can buy it!"

Keating, after some argument, called Mallory again. His ear burned as he heard the Radium King's opinion of the matter, but Mallory finally gave his consent.

"We'll just break even on it," wailed Keating. "We save our guarantee, but we lose our percentage for the sale. Sommers gets that."

So the matter was arranged. Sommers promised to return the radium by Monday, and Keating, as a parting shot, angry and frustrated, formally discharged the chemist.

"But my contract," grinned Sommers: "You'll have to pay me fifty a week for the next year anyway."

"All right," shouted Keating: "We'll see! You've held us up, Sommers, but you can't get away with it l"

"Don't forget to bring a certified check Monday," said Sommers mockingly: "And give the boss my love."

CHAPTER V

Clues to Spare

DETECTIVE Moran and Young Lawson, the chemist, sat together in the quiet restaurant, having a belated supper. They talked of the radium theft, and of the many leads which Moran saw with his detective's eye.

"This Sommers now," said the detective, over his steak, "he seems sore as hell at Mallory."

"And no wonder," said Lawson: "But you must watch him, Moran."

"I've got all these fellows listed, who worked there. Some one of them ought to lead us to the thief or thieves."

"The radium should turn up," said Lawson: "Moran, at first, I saw nothing in this case; but I am willing to stay with you now."

"I thought you might be interested," said Moran.

The detective did not guess Lawson's eagerness in the case. He, busy with his work, had failed to catch the young chemist's look at Edith Mallory. But Lawson, whose heart sang strangely for him, had a vision of the young woman before him.

And now, picking at his food, he contemplated ways and means of seeing her again. As Moran's side partner, he might have access to the Mallory home.

The case had not yet shaped itself in his mind. There were too many clues to follow, all vague.

"Radium must turn up, Moran," he repeated, time and again: "No one could have any use for it that I can think of. Save perhaps a research chemist, who could not afford to get it. But that's a wild hypothesis! Take Sommers, for instance. Have you set men on him?"

"Yes, And I've sent shadows to keep tabs on the movements of the whole damn personnel of the factory!"

"The radium should turn up," said Lawson again: "It is only a small inch of white powder, Moran; but if you were to hold it in your hand for any length of time, it would cause your internal organs to alter, and would burn you with ulcers, fatally in the end. Your blood would become anemic, for it attacks the corpuscles and burns good flesh as well as foul. In the hands of a skilled worker, the rays are of immense value in treating malignant growth, cancer, tumors and goiters. Small tubes of glass, with a tiny amount of radium salt, are placed in a wound or on it; the dead tissues are destroyed. But the worker must be protected. Lead-impregnated rubber gloves, a lead screen of some centimeters in thickness, must be used. The gamma rays, which are powerful X-rays in effect, will plow through centimeters of lead. Yes, it is dangerous stuff for a common thief to carry around with him. The stolen radium was in a round lead box, five centimeters thick. In the block of lead were small holes, into which the glass tubes, each containing a gram of the salt, were placed. The cover fitted tightly over the bottom, and the whole was placed in a leather case. The radium could not escape."

Moran shook his head. "It's wonderful stuff," he said: "Somehow, I hope, when I find it, it's still safe in that lead box!"

"Moran," said Lawson, leaning across the table, "a skilled chemist took that radium! I'll bet you a nickel I'm right. It would take such a man to handle it. And someone with a grudge, too, or he would not have destroyed the plant!"

"Enemies? Sure!" Moran grinned: "Thousands! Far as I can make out, everybody dislikes old Mallory. He's a son-of-a-gun! Don't like him myself."

"It might have been Sommers, of course," said Lawson: "And then again, it might have been any of the others who worked for him. But watch Sommers carefully."

"And what about Leopold?"

Lawson was silent: "I don't know. As the thief, he seems actually impossible to me. I don't think the Belge Company would go to such extremes to ruin Mallory. Besides, if they knew the radium was gone, they would have had some at hand to fill the order."

"Maybe they're in league with Sommers."

"Possible. But not probable, because why should a man like Leopold bother to shake Mallory down that way? He could easily have raised the price a little, if he wanted some for himself. That's all. But better keep your eye on Leopold as well."

"It's some job," said Moran, shaking his head. "There's too many clues; but none of them, except perhaps Sommers, points anywhere. However, I fill get to work right away."

"How about the fog?" asked Lawson.

Moran threw down his napkin with a curse: "I'm going crazy, trying to get a start on this business!"

The Marauder

YOUNG Lawson, research chemist of the Margeaer Society, stood with one test tube held over another. It was the middle of a busy day. Outside, in the general laboratory, the rank and file of the chemists worked on milk cultures and general analysis. Lawson, in his own room, a privileged being with a free hand to experiment as he would, was strangely disturbed.

And, for the first time, it was not the atoms and electrons which held his interest; no, he was upset that he could not concentrate on them as he should.

The radium case, on which he had promised to help Moran, had baffled him; for there was no way to get a start at working.

However, Lawson, whose single passion had been chemistry, found the science less absorbing than formerly. Between the retorts and reactions had interposed the face of a woman. Lawson, supposedly hard at work, was idling his time away in dreams of Edith Mallory.

He had seen her but twice. For three days now—it seemed three eternities to him-he had not had a glimpse of her.

Detective Moran had been out working, directing the search for the radium thieves. Lawson had had no word from him; for, when last they had met, Moran had said he would call on Lawson when he got a workable clue. And no word had come.

The chemist poured slowly from one tube to another. Red turned to green, then to deep blue. He cursed and threw both tubes in his waste barrel. A graduated tube, in which was a pink liquid, with a rubber hose clipped shut at the bottom, occupied him for a few moments, but he was restless. His hand trembled, and too much liquid entered the beaker.

"No use," he muttered. He stood for a time in revery; then he evidently came to some decision.

Taking his hat and top coat, he left the laboratories, and went out into the sunshine. He sighed deeply, and started towards the river. For the rest of the afternoon, he alternately walked and sat on benches, thinking of the girl.

Towards seven o'clock, he remembered he had not eaten all day; so he dropped into a restaurant and drank coffee. A phone booth in the place invited him to call Moran—for Moran might have some news of Her. But Moran was not in; had been out all day, according to the sergeant who answered.

Darkness had fallen when Lawson, the man of science, finally walked with faltering steps to the Pennsylvania station. A Long Island train took him to the town on the outskirts of which was Mallory's estate.

He hoped to have a glimpse of the girl. Perhaps, his heart said, she would appear at a window, might even come out, and, seeing him, speak to him. He sighed. His brain called him a fool; but he could not resist his desire at least to see the house in which the idol of his dreams lived.

It was some time before he could muster up his courage to go by the grounds of the estate. There was a light in the lodge, at the big gate, and the chemist shunned this place. But there were smaller side gates in several spots, and Lawson, taking his courage in hand, slipped into the grounds.

The big mansion, set back among the trees, was lighted in several of the downstairs rooms. Mallory's apartments, in the rear, were dark.

He crossed the lawn stealthily, ashamed of himself, his heart beating hard. He had no right there, he knew.

Would she appear? A glimpse of her at the window and he would have felt rewarded.

He stood within fifty yards of the mansion, and tried to muster up courage to go and ring the front door bell.

So absorbed was the chemist in his thoughts, that he did not see the stealthy dark figures which crept towards him across the lawn skulking in the shadows of shrubbery, crawling almost on their bellies across the open spaces.

Suddenly, he was leaped upon from behind, and with a stifled cry, he felt himself borne to the grass and held in a grip of iron.

The Gunman

"KEEP still, you," growled a heavy voice, and the muzzle of a gun was jammed into his ribs.

They searched him professionally, but found no weapons. Lawson, chagrined, at the mercy of the men who had leaped on him, found all his natural fear of the attack submerged in the ignominy of his position.

More figures were running across the lawn. Lawson, with infinite relief, heard a familiar voice.

"What have you got?"

It was Detective Moran. The sturdy figure stood over the prostrate Lawson, as flashlights illuminated the chemist's face and form.

"Well, for the love of heaven!"

Moran stared at his friend for several seconds. "Get out of here," he snarled at his men, who had brought the chemist down: "Don't you know Dr. Lawson?"

The others retired. Moran pulled Lawson to his feet and brushed off his clothing. "Fools!" he repeated.

Lawson laughed: "I'm the fool, Moran. I did not know you were out here. What's up?"

"We got a call last night that marauders were around the estate," said Moran. "Mallory asked for police protection. I thought we'd caught something when we got you."

"Marauders?"

"Yes. Mallory and his daughter were out. They sometimes go to the city together, to a show. One of the servants, who happened to be in the front of the house to answer the telephone, heard noises outside. He looked out, but could see nothing because of a fog that had come up."

"A fog, Moran?"

"Yes. I thought maybe, being near the water, there'd been one here; but nobody in the neighborhood saw any fog. However, this footman says there was a fog and he couldn't see anyone outside. He went through the house downstairs, but found nothing. He returned to the servants' quarters and got the butler and a couple of other fellows, and the four of them went outside, and they all claim they were in a thick mist. Finally, they went upstairs. They came to Mallory's quarters, and found distinct signs of an intruder having been there. A window was unlocked—a window which gives out onto that low balcony you can see at the rear of the house. But they didn't catch anybody. They reported the incident to Mallory when he returned, and he called me and asked me to send some men out."

"Was it burglars, do you think?"

Moran shook his head slowly: "They didn't steal anything, if it was. Of course, they may have been frightened off."

"And then," said Lawson, "there's the matter of that fog, eh? Strange it should happen twice!"

Moran nodded gloomily: "You said it. It's got me."

"Anything else?"

"No. I haven't got the full reports in yet. I've got men on the whole shebang. But tell me—how is it you're out here?"

The detective looked searchingly at his friend. But the light was dim, and the detective missed the flush which Lawson could not restrain.

"Oh—I came out to have a look around."

"I hoped maybe you had something and were looking for me."

"No." Lawson came to a sudden decision: "Moran," he said, "appoint me a shadow, will you? Let me keep my eye on the mansion. I'll work for you out here."

"Huh? Why should you waste your time fiddling around here?"

"I'd like to, that's all."

"Well—if it'll give you any pleasure, stick around. I'll not be out much. Was just getting the boys set. We'll watch for a few days and then, if we don't catch anybody, we'll figure it as burglars."

"Did you find any footprints?" asked Lawson.

"Oh, a couple, in the grass below the balcony. But whoever it was traveled on the gravel paths. He left no trail."

CHAPTER VI

The Lead Box

"SUBJECT came out at 8:45 A.M. Walked to bakery, where he purchased ten cents' worth of rolls. Returned home. Greeted by wife, blonde, about twenty-six. Remained indoors all day, in the rear of house, where he has a chemical laboratory. At six P.M., appeared with wife; and the two went to supper, both in high spirits. Then to theater, a musical comedy. Went home and retired. Met no one. Nothing unusual from regular routine."

"Can you beat that?" said Detective Moran, despairingly, handing the sheet to his friend Lawson.

Lawson looked over the operator's report. Four of Moran's best shadows, man-hunters who missed nothing that went on, had been set on Charles Sommers, the young research chemist who had shaken down the Malloradium Company for fifty thousand dollars. For ten days, he had lived quietly at home; experimenting in a small laboratory of his own in the attic of his suburban home; going out occasionally, but acting in no way suspiciously. Likewise, the other employes who had worked for Mallory had been shadowed. It had taken a hundred men to investigate them; and of all these possibilities not one had proved of value.

Nothing had come of the watch outside Mallory's home. Lawson had spent most of his waking time on the grounds. He had been rewarded several times by a sight of the young woman, Edith Mallory. Once she had seen him, during the day, and had smiled on him.

But, now, he no longer had any excuse to visit there, for Moran had called off his shadows in disgust. The marauder had failed to walk into the trap set by the police.

"And Leopold?" asked Lawson, who was seated on Moran's desk, swinging his legs as he watched the lines of worry on his friend's brow.

"Hell," exclaimed Moran: "Nothing there, either. Leopold has not stirred from his regular life. Sommers went and got his check Monday from Keating. He met Leopold and Tollerman and Keating. I was hidden, to observe them. Sommers laughed in Keating's face. Now, plenty of employes of Mallory have been moving around. One chemist, named Smythe, went all the way to Buffalo, and I thought we would get going; but he was only after a new job. It was the way with all of them; they were after a new place to work. That was natural enough, since they were thrown out by the wrecking of Mallory's plant."

The radium bought from the Belge Company and obtained from Sommers, had been delivered on time to the new Boston bank, at the hospital; so that Mallory had saved the forfeit money.

"What's Keating been doing lately?" asked Lawson.

Moran grinned: "Still looking for that radium in the ruins. Guess he's been over them fifty times! He'll never find it."

Just then the phone rang at Moran's elbow. The detective picked up the receiver. He listened for some time.

"Well, for the love of heaven!" He hung up and turned to Lawson. "They've found the radium! Keating just called me to tell me he discovered the box within a few yards of where the blown safe was."

Two hours after the news from Keating of the finding of the radium, Moran, accompanied by Lawson, stepped from their car to the front door of the Mallory home. They were taken upstairs to Mallory's apartments.

The Radium King was strangely subdued. He was almost polite to his visitors; if a quiet voice and a disposition to listen without interrupting can be termed politeness.

Keating, radiant and happy, was there. In his hand he carried a round leather case. Inside the case was a heavy lead box, with walls some two inches in thickness, and inside the box were holes into which fitted small glass tubes containing amounts of white salt.

"Boss, it was wonderful," he cried: "I swear I looked there a hundred times before! But today, I was poking around as usual, and I happened to turn over a burned board; and there, lying right in front of me, was the case!"

"I'm very glad," said Mallory: "I've not been well lately, Keating. The loss of that radium would have just about ruined me. Now we can fill our other orders. Do you think there's any chance of the Belge Company buying the extra ten grams from us?"

"I'll see. They might help us out."

"Let's hope so." Mallory turned to Moran: "I'm very much obliged to you for your assistance. I'm sure you've done everything possible to help us. As there were no thieves to catch, it's no wonder you didn't do it."

"I'm happy to have been of assistance," said Moran, "and glad you've recovered the radium. We'll call our men off now. Any time we can help you out again, let us know."

Lawson, standing quietly behind his friend, had a sinking of the heart. While he tried to rejoice that the radium had been found, still he knew that he would no longer have any excuse to see Edith Mallory.

The girl came into the room, as the three were about to leave. Mallory, who had, on the previous occasion when they met there, been too wrought up to remember small things like the social amenities, introduced his daughter Edith to Moran and Lawson.

CHAPTER VII

A Fresh Stimulus

THE chemist took the small hand she graciously held out to him, and a thrill passed through him.

"I'm happy to know you," she said.

Words, which could express so little! Lawson mumbled incoherently. He found courage to look into her eyes. He caught the kind gleam of them, and the recognition of himself.

"Come along, Lawson," called Moran, from the doorway.

Keating was jubilant. "Everything's O.K. now," said the manager: "The boss will have to admit I was right, and so will you, gentlemen. I knew no one would steal radium."

"Well," said Moran, "it sure looked like it for a while. It's still a puzzle to me."

"What are you going to do now?" asked Lawson. "I'm going to put this radium bromide in a safe place," said Keating: "In the thickest, best-guarded vault I can find. Then I'm going to go and see Leopold and find out if he'll refund us our money on the stuff we bought from him. I think he will. The Belge Company has always been every decent in its dealings, and will hardly refuse my request. I hope the boss gives me that $25,000 reward."

Lawson was sad. He had met Edith Mallory, only to lose his opportunity of seeing her again. He had no excuse now to go to the mansion, and there was little chance that he would ever meet her in the natural course of events.

Then the chemist, about to enter Moran's car, had an idea. Keating! He would become friendly with the manager, and in that way, he might be able to establish contact with Edith Mallory.

"I'll see you again soon, Moran," he said, hurriedly.

The surprised detective watched Lawson as the latter spoke a few words to Keating and then climbed in the manager's car.

"He's been acting funny lately," thought Moran. But cases had been piling up and the detective knew there was plenty of work awaiting him at headquarters. He started off, waving goodbye to the two behind him.

Keating, talking rapidly, well pleased with himself, drove into the city, and stopped at a bank vault, where he deposited the lead box. Lawson, tagging after him, accompanied him next to the offices of the Belge Company.

Leopold was there, and when Keating and Lawson were shown in, he received them cordially.

"We've found our radium," said the manager.

"That's good news. I thought you would." Leopold was glad: "It's an unlikely thing for anyone to steal. But how can I help you now?"

"I've come to see about getting a refund, selling you ten grams of our stuff," said Keating.

"H'm. It's disappointing to lose a sale; but I think it would only be ethical for us to consider it. I will have to cable abroad and confer with Tollerman about it. I think it can be arranged. That is, we will take ten grams off your hands. Naturally, you lose your commission."

"That's fair enough. Let me know what the result is as soon as possible."

"Yes, surely."

Keating was a busy man. Lawson was forced to leave him soon after, for the manager was oblivious to the chemist's desire to become better acquainted.

Lawson returned sadly to his rooms.

He was again called from his laboratory, two days after his introduction to, and what he feared would be his last sight of, Edith Mallory.

"Hello, Lawson, 's Moran."

"Yes? What's the trouble?"

"Plenty! Keating was just here."

"Well?"

"Can you come over? I'm at the office."

"Yes. I'll be right there."

In Moran's office, the detective grinned at his friend the chemist:

"We were right, after all. That radium was stolen."

"I thought it was found?"

"So did everybody. Keating did, Mallory did, I did and you did! D' you know what happened? Keating gets the Belge people, Leopold and Tollerman, to say they'll take back ten grams to make up for what Mallory had to buy from 'em. So he delivers the ten grams this afternoon; and he calls me to report that on analysis the salt in the lead case was nothing but salt!"

"You mean common salt?"

"Yeh!"

"Sodium chloride!" Lawson passed his hand over his brow: "Heavens, Moran; what do you make of that?"

"Don't know. Can you figure it? It wasn't possible for the Belge Company to crook Keating, because he himself was right there while they looked over the stuff!"

A Cruel Trick

LAWSON, with knitted brow, rose and paced up and down the room. "This will be a blow to him-and to her," he murmured.

"Eh?" said Moran.

"Nothing."

For several minutes, the chemist ruminated: "Weren't there men watching the ruins?" he asked.

"Yes. A couple of guards."

"And did they have anything to say?"

"Keating never questioned them after he found the radium—or thought he had found the radium. But today, I went and located them. D' you know what they said?"

"Yes," said Lawson suddenly: "They said that the night before Keating discovered the radium, there was a thick fog over the ruins. And there was no fog, anywhere else."

"You're right."

Lawson ruminated for some minutes. Then he turned on Moran. "Moran," he said, in a grave voice, "there is an evil spirit operating in this case. What a cruel trick that was, to plant the radium case with common salt! It is consistent, however, with the operations of this unknown person, who all along has played his hand well. Moran, I'm going to find him."

"That's the way to talk," applauded the detective: "I'm putting men back again on Sommers and the rest. "Only—well, if Sommers had planted that stuff, we'd have trailed him to the works and caught him red-handed! See? This only throws us out of gear all the more."

"I will find him," said Lawson. Then he added, under his breath, "for her!"

* * * * * *

It was late afternoon. The red sun was sinking behind the trees of the Mallory estate as Young Lawson, in a hired cab, drove up to the great gate and was admitted by the lodge keeper. A few moments later, and he was inside the reception room, waiting with strangely beating heart.

A light step sounded from the corridor, and then Edith Mallory stood before him.

"Hello, Dr. Lawson."

She held out her hand and smiled on him. He could not speak for a moment as he looked at her. It was her air of quiet assurance that had charmed the chemist as much as her beauty; that, and an attraction towards her which amounted to magnetism.

She sat down, and he took a chair near her. She waited, after a conventional remark or two on the weather. Lawson at once came to the object of his visit.

"Miss Mallory," he said, trying to be as businesslike as possible, "I don't know whether you know just who I am or not."

"Mr. Keating told me something about your work and reputation," she said. Then she added, smiling, "I asked him about you."

Lawson flushed with pleasure; but he strove to stick to facts. "I have come to help your father and you in this business of the stolen radium," he said: "I want to get all the facts possible from your father. Now that the thief or thieves, whoever they were, have appeared again, it is obvious that some malignant entity is working against your father. Anyway, I am sure we have to do with a man who knows chemistry, and knows your father and hates him. The first, I believe because of the way the radium has disappeared, and the planting of common salt in the lead box. What use, beyond the fact that the loss of the radium bromide might ruin your father financially, the thief intends to put the radium to, I cannot even guess. It can't be sold, that's certain. It's value is too fabulous for the thief to realize even a fraction of its worth. He is evidently an enemy of your father, for the spite of returning to plant the sodium chloride; raising your father's hope and then dashing it to the ground, and the fact that marauders have been upon the estate, point to this."

The girl listened gravely.

"I fear the same thing," she said: "Some person wishes to ruin father. But why did the marauders come here? The theft of the radium is enough to cause bankruptcy, the expense of its extraction is so great. What I fear now, is that this enemy may have come to kill father!"

Her fists were clenched. She was nervous, under her forced calm. Lawson—who had thought of the same thing, but had not wished to alarm her to too great an extent by telling her that he believed the marauders had come to kill her father and been disappointed because Mallory was out—could only nod.

"Well," he said, reassuringly, "the thing to do is to set guards about the house again. Do you think I might speak with your father now?"

The girl shook her head: "Father is not well. The worry and anxiety about the radium has, I believe, made him ill. So our physician, Dr. Morse, thinks, too. He has dermatitis and has grown so irritable that I'm the only one who can talk to him."

"The radium should turn up some time," said Lawson. "The burglar could scarcely use it."

She nodded. She rang a bell and ordered tea. The two chatted of this and that, and the young man was pleased to discover that Edith Mallory knew a great deal of chemistry. She had taken a course in the university in science.

Two hours passed so quickly, that Lawson was amazed to realize that it was dark, and his wrist watch said seven o'clock.

"I am going to begin my own investigation," he said: "You see, while I work for a private company, Moran lets me assist him sometimes. I have solved a case or two for him."

But he had already told her the history of his eventful chemical life. She smiled on him as he shook her hand.

"If I can help you, at any time, don't hesitate to call me," he begged: "Here are my office and home phone numbers. I'll be glad to assist you at anytime."

She thanked him, and accompanied him to the door. The chemist walked down the gravel drive which led to the gate, with wings on his feet, and a song in his heart.

CHAPTER VIII

More Guards

THE chemist went to Moran's office, and waited until the detective came in.

"What's up?" asked Moran.

"I was going to ask you the same thing," said Lawson smiling: "Moran, my theory is that the man or men who were out there that night on the Mallory place, came to kill him. I don't believe you ought to leave it unguarded. There is Mallory's own staff around, but you know they can't watch a place the way your shadows can. Send out Harte and Ulman."

The detective was unconvinced: "I figure it was just some second-story man," he said. "I've got Harte and Ulman on young Sommers. You know, we've sent out warning to all the possible places where radium might be sold, to let us know if any which can't be checked turns up."

"That's right. But better send your two best shadows out to Mallory's. I want them there."

Moran scratched his head. "You been out there?"

"Yes. Two hours."

"Did you see Mallory?"

The chemist flushed slightly. "No, Moran. I was talking with Miss Mallory."

It was a long time before the detective spoke. Lawson sat under the light, and Moran, after looking at him for some seconds with a puzzled face, began to smile. The smile started with his eyes, then spread to the cheeks, then to the lips, and finally became a broad grin.

He slapped his leg, and drew back his head. "Now I've got you," he cried delightedly: "By golly, it's funny I didn't guess it before!"

"What?" said Lawson testily.

"Go on! You can't kid your old friend Moran. You're sweet on that girl!"

Lawson was irritated, but he knew that to allow Moran to see it would only please the detective. He waited until Moran's mirth had subsided.

"Whether that's true or not, Moran," he said, "we're got to find the radium."

"All right," said Moran. "You've helped me plenty, and now I'll help you. I'll send Harte and Ulman out there tonight. No one shall touch a hair of her head if I can help it."

So the two shadowers were dispatched to the Mallory estate.

* * * * * *

"Now, listen, Moran," said Lawson: "Somebody is trying to get Mallory. That's almost obvious. They have broken him by stealing this radium, and now I think they want to kill him. They were disappointed when they got out there and found him not home."

"None of these fellows we're watching was out there," said Moran.

"Then it was not one of them. But it might have been an accomplice."

"What do you suppose all the talk about fog was?" asked Moran.

"That is the simplest thing in the whole mystery," said the chemist: "Why, Moran, what do you do when you have a criminal bottled up in a building and want to get him out without exposing yourselves?"

Moran slapped his knee. "Why, of course! You mean it was just a smoke screen?"

"Yes, that's it. That's another reason I say a chemist is at work. But we must not let anything slip, Moran. There are only a few works where such gases are made. Look them up, and see if you have any luck that way. But, personally, I believe the criminal manufactures the stuff himself. It's easy enough. Silicon tetrachloride, for instance, is a colorless liquid, but when it comes into contact with air, it gives off thick white fumes. The water in the air decomposes it, forming silicon hydroxide, a white substance, and hydrochloric acid. Also, if dry ammonia is mixed with the silicon tetrachloride, more white clouds will be formed; because the hydrochloric acid unites with the ammonia to become ammonium chloride. This and titanium tetrachloride were much used in the war to lay smoke screens, Moran; the smoke screen is also used by you fellows to protect yourselves in the open against desperate bandits. What would prevent the bandit turning about and using it to protect himself?"

"Makes no explosion when it starts, either," said Moran: "Well, that's that. I'll look around and see if I can locate anybody who's been buying smoke."

"Probably the thief makes it himself. As I said, I believe we have to do with a man familiar with chemistry."

The Call

SEVERAL days had passed. Moran had reported no luck with his investigations. Harte and Ulman had not been able to catch any trespassers on the estate, but, acting under orders, they alternated with another pair of shadows who watched during the day.

Lawson had been in touch with Keating. He had requested the manager to rack his brains, in the effort to think of someone who might be so bitter an enemy of Mallory as to plot destruction and death for the Radium King.

It was the absence of a visible motive which blocked the investigators at every turn. There were plenty of men, like Charles Sommers, who might wish Mallory bad luck; but no one could be traced who would go to such lengths to get revenge.

Lawson had promised to find the stolen radium; he had told Edith Mallory that he would do so. He had been out to the estate twice again to search for traces; but the ground had been trampled by many feet, and nothing remained, even if there had been anything in the first place. He had spoken with Miss Mallory on both occasions, but her father had been growing worse.

'Lawson sat in his bachelor quarters that night, his feet on his desk, slumped down in an armchair. His head rested on his breast. His thoughts reviewed the radium theft, but always returned to the girl.

It was about eight o'clock. The phone bell rang, and Lawson, picking it up from its stand, answered. His heart leaped when he heard the voice of Edith Mallory.

"Dr. Lawson?"

"Yes. Miss Mallory?"

"Yes. Dr. Lawson—" there were tears in the voice—"I—I am calling to ask your help. Father is worse. The physicians say he may die. I—I don't know what to do. He has growing sores on his body and his heart is in terrible condition. I don't know where to turn for help. You told me to call you if I needed you."

"Yes, of course. Will you allow me to come out there?"

"I wish you would."

"Is your father delirious?"

"Yes, he is at times."

"I will come at once."

The chemist packed a bag, and caught a train. He arrived at nine o'clock, and was admitted by the gate keeper. He was aware that shadows, watched him and knew that Moran's faithful bloodhounds were on the job.

The young woman greeted him with tear-strained face. "Father is in his apartment," she said: "He has been in bed now for several days. He cannot eat, and is growing weaker."

Lawson's heart was torn, by the sight of the girl's grief. He tried to comfort her but she loved her father and her inability to help him made her frantic.

"Something must be done! Something can be done," she cried. "Oh, help me!"

"May I talk with the physicians?"

"Dr. Morse is here. There are two skin specialists, but they come in the morning."

Dr. Morse was a heavy-set man, with clean-shaven face and black eyes. He seemed rather to resent the intrusion of Lawson, whose degree was Ph.D. But he came out into the hall at Miss Mallory's call, and answered Lawson's questions.

The Evil Attack

"YOU say ulcers have appeared, after dermatitis?" asked Lawson.

"Yes. And the internal organs are deranged. The heart and stomach are not functioning properly. Also, a blood test shows pernicious anemia."

"Well, then, Dr. Morse," said the chemist, "this points to exposure to radium. Do you realize that?"

The doctor shrugged: "My dear fellow, we have diagnosed it as such. We are treating the burns with scarlet red and zinc oxide. To keep them clean and prevent their spreading is the most we can do. What baffles us is that the patient shows no improvement, but grows steadily worse. It is easy to see how he might have been burned at some time during the course of his work with radium. The burns may not appear for as long as two years, and, again, they may show in ten days."

Lawson nodded. From the other room, a shriek went up, an eerie cry which penetrated the flesh and caused the girl to scream in terror and sob violently.

"Oh, poor father!"

"Hush," ordered Lawson, gripping her arm. The chemist stepped into the sickroom, lighted by a single lamp. A white-clad nurse hovered near the patient.

Mallory heaved on the great bed.

"Fire," he cried: "Fire! I see fire! Oh, God, my eyes!"

The Radium King, a broken, pitiful creature now, writhed in agony.

"James—Nora—Edith. My eyes! Curse the luck."

The chemist's high brow was corrugated with heavy wrinkles. Outside the door, he could hear the sobs of his sweetheart, crying for her parent's pain. Lawson stepped outside the room.

"Doctor," he said gravely, "do his words mean nothing to you?"

"Eh?" said the surprised Morse. "They are ravings, that's all."

"Perhaps they are. But they have a significance. Now, I want to investigate the room. Please tell the nurse that I am to be allowed the run of the place."

Morse hesitated. He did not like this interference with his authority. "Of course, doctor," said Edith Mallory, "allow Dr. Lawson to do as he likes. He is a friend and a famous scientist."

The doctor stepped aside. Lawson entered the sickroom again, closing the door after him.

Fifteen minutes later, he came out, his eyes grave.

"Dr. Morse, you must move Mr. Mallory at once. Do not allow anyone to enter the room again, or the bed to be used."

"The patient should not be moved," said Morse, "in his present condition."

"He must be moved. I will move him myself if you do not. He is burned by radium, and he is being burned more. I don't want anything disturbed in the room, but Mr. Mallory is to be taken to another bed."

"On whose authority do you issue these orders?" asked Morse coldly.

"On my authority," said the girl, her eyes flashing.

Morse obeyed, grumbling. Ten minutes later, and the sick room was empty. Mallory had been carried down the hall, and placed in a guest room.

Then the three, Morse, Lawson and the girl, went downstairs. The nurse was left in charge of the patient.

"I'm going outside for a minute," said Lawson. He went to the front door, and stepped out into the night. "Ulman, Harte," he called softly.

A moment later, and a dark figure stepped up to him: "It's Detective Ulman. How are you, Dr. Lawson?"

"Very well. But I want you and Harte to watch Mr. Mallory's former room very carefully. It's the fourth window from this side, in the rear, where the balcony is."

"Harte is there now."

"Very well. Don't let it out of your sight for an instant. Keep under cover yourselves, so you will not frighten anyone away, do you understand? If anyone comes, let him get into the house; but do not let him out."

"Yes, sir."

Lawson returned to the hall, where he found Morse about to take his leave. "I'll be here in the morning," said the doctor: "If he grows worse during the night, call me at once."

The girl and Lawson were left alone.

"Why did you have father's room changed?" asked the woman.

Lawson's eyes were grave. "Because, Miss Mallory, from your father's words, uttered in delirium it is true, but significant to me, I became almost certain that he was being exposed to radium. It makes the eyeballs luminous—not so that it can be seen by an observer—but the exposed person's eyes gleam under the lids so that, when the eyes are closed, there is a glow which is maddening. This is but a temporary effect of radium; it would have passed off instead of growing worse, had your father been burned at any previous time. That and the fact that he is only getting worse, made me sure that he must be under the influence of radium while he lay in bed.

The Deadly Enemy

The girl gasped: "Then you think—"

"I think there is a cruel and deadly mind with which we have to deal," he said: "It is for this reason I do not wish anything to be disturbed. Have the reporters been calling you at all Miss Mallory?"

"Yes. Every day, to ask how father is. It is known he's ill. All our acquaintances inquire, too."

"Well, when they next call, tell them that he is much better and will get well. Tell them that he has been removed to another room, but do not give the real reason. This is important. Will you do that?"

"Why, of course. But do you think he will recover?"

"Yes, I think he will get well. Now that he is out of the radium's vicinity, he ought to improve rapidly if correctly treated. But report it as already accomplished, will you not! Tell the doctors to do so, as well. It is important."

She sobbed with relief, as he repeated that he was sure her father would recover. He could not resist taking her hand in his.

"Oh," she cried, "I knew that you would help me! I felt it, Dr. Lawson."

"Call me Young," he begged.

"Yes, of course I will. And you'll call me Edith, won't you? It's been hard, to have no one to call on, no one to depend on. Father and I have always been close together. In spite of his temper, and many bad points, I adore him. He's always been good to me."

"I love him for that, then," said Lawson, in a low voice.

The girl grew calm as the chemist talked to her soothingly.

"Will you stay here?" she asked: "You can have a suite."

"Yes. I thought I might be needed, so I brought a bag. I have been growing steadily suspicious concerning the proximity of radium to your father; and I wish to see if I cannot trap the thief. I will tell you that I have located the radium stolen from your father, of that I am almost certain."

"Oh," she murmured, "I think you're wonderful!"

"I have in my bag a spinthariscope, an instrument used in identifying radium emanation. It is formed of a zinc-sulphide screen, which glows when the alpha particles strike it There is a magnifying glass which helps to identify the glow. You know, it is thus that the luminous paints used on clock dials are made."

She accompanied him to the door of the bedroom which her father had formerly occupied. Lawson ordered her to remain outside.

"It is dangerous to enter the room," he said. "I will not be surprised if the nurses and physicians develop burns."

"But you," she cried. "If it is dangerous for me, it is for you!"

She held him back, and would not allow him to make the test for /radium then. He promised to wait until the next day, when he would be able to go to the city and obtain lead impregnated gloves and a screen behind which to work.