Help via Ko-Fi

SCIENTISTS admit that we are now on the verge of great discoveries in biology We are Just learn any what we human beings are and what the forces are that control us. Why are some men small and others tall; why are some witty, clever, strong and successful and others dull, stupid and apparently without purpose or energy in life? The answer of the biologist is: Glands-little reservoirs of strange fluids, the fluids that course through our blood and determine our destiny. This seems almost magical—that for example a few drops of an unknown fluid can determine a man's entire destiny. Yet it has been proved to be true.

What a world we will have then when we finally discover how to control these glands and make them do for us what we will! We may have a nation of supermen or a nation of strong, stupid, slavish servants. It will all depend on who controls the glands. The author of this exciting tale was a professor of medicine himself and his science is not only exact but his story most thrilling.

An Army of Merciless, Inhuman Creatures were ready, . . . Under the Master's hand they armed for action . . . then Nature entered the play . . .

TO many who read my account of our amazing adventure on the island of the Gland Men, it will serve as just another illustration of how devious is the path of science. It will illustrate also how, from the darkness that girds it round, terrible possibilities loom black and menacing, terrifying those daring enough to wander from the beaten track.

Another, and I fear greater section of my readers may harbour no such sentiments, labelling the whole as a tissue of preposterous lies, but to those who condemn me, I say this. Take the facts—meagre, garbled—as they appeared in the newspapers and attempt to account for them in any other way. There is only one answer. It is impossible.

The intimate details were far too terrifying and astounding to permit of the facts being published verbatim, and it was mainly due to the newspaper's reticence that something bordering on a worldwide panic was averted.

Doctor Bruce Clovelly, DD., F. R. C. S., will, of course, need no introduction, for his recent surgical triumphs in glanding have made his name almost a by-word, and it is with Guy Follanshee that we must concern ourselves. Follansbee, as I knew him in my days as laboratory assistant to the doctor—one of those singularly fortunate individuals who know exactly what they want and how to got it without offending a single soul—inclined to be cynical, yet straight as the proverbial string. He had inherited from his father an insatiable desire for adventure and an income that ran into I forget how many figures. Being a man of somewhat simple philosophy, he used the latter to appease the former.

It had taken our combined arguments, practised often and over long periods, to make the doctor even consider such a thing as recreation and I had experienced the hardest task of my life in getting him from his chambers in Cower Street, to which he clung like Diogenes to his wooden cavern. Even after his actual transplanting on to his opulent friend's yacht, the Silver Lady, he took his enforced holiday like a small boy takes his medicine, but as the illimitable miles of sparkling water grew between our vessel and his stuffy chambers, he turned about to enjoy himself.

We were midway between the Solomons and Santa Cruz islands when the queer affair began. The morning had been oppressively calm and Follansbee, the doctor and myself had taken the electric launch to examine the rock fauna that flourished so prolifically hereabouts. It was characteristic of the doctor that he could, when required, produce inexhaustible stores of unexpected knowledge on the most out-of-the-way subjects; and though I had never before heard him mention marine growths, here he was expounding in his most didactic manner to his slightly amused companion.

Having little taste in such matters, I was reclining upon the collapsible canvas chair, smoking a cigarette, and occasionally dipping my hand into the water, in order to convince myself that it would not emerge dyed blue. Whether, rocked by the gentle motion of the boat, I fell into a semi-doze or whether the change swept down so quickly that its coming was unnoticed, I cannot say. But I remember that I suddenly jumped to my feet and called my companions' attention to the unpleasant condition of the weather.

In the east, the sun, flattened lo a disc of unhealthy brown, was gradually giving way to a dense bank of cloud that rushed down with the rapidity of a drop curtain. The water had lost its turquoise hue and undulated in a long oily swell that was strangely suggestive of hidden power underneath. Everywhere a heavy, pall-like silence hung over the face of Nature, fraught with an indescribable sensation of impending danger. Now and again there sounded, very faint and far-off, a curious humming sob, no of some gigantic beast in an agony of torture.

"Without the slightest intention of being a first class Jonah," it was Follansbee's first remark as he boarded the launch. "I should say that we were in for something extra in the way of dirty weather."

Doctor Clovelly shrugged his shoulders. "I should have expected something like this to happen," he said irritably. "We should have never left the yacht. What are our chances worth if it catches as in the open sea?"

The explorer snapped finger and thumb. "Just that," he said grimly. "The only thing possible is to cut for the nearest island. With the weather like this the storm may be on us in five minutes, but on the other hand it may hang off for hours." He swung the wheel as he spoke and the launch cut thru the swell with a curious sticking motion. "But the Lord help us," it was Follansbee speaking again, "if it brings typhoon in its wake."

I LEANED over the side and glanced at the approaching is-laud. Through the haze, I discerned the woods that flanked the shining stretch of silver sand, unsullied by mark or impression, the thick vegetation that grew, tangled and luxurious, down to the water's edge. Here was a tumbledown native hut, raising its battered head above the mass of tropic greenery, there a sturdy giant palm, the trunk hidden from view by the enveloping folds of some flaming parasite. As we neared the beach, I saw that the land sloped sharply into rolling hillocks, cut and serried by deep gullies whose black, forbidding extremities were lost beneath the shadow of the higher mountains.

I turned to our host. "Does it possess a name?" I queried.

He shook his head. "Probably one of the numerous islands that stud the Polynesia like stars in the Milky Way. They are here today and gone tomorrow, thrust up by some I volcanic eruption, sucked under the sea by a tidal wave or some similar undersea disturbance."

"I sincerely hope that it remains stable during our occupation," I remarked. Then the launch grounded on the shore and I jumped out to aid Follansbee to beach it high and dry. This done, we took our first close look at the island, our enforced landing place.

As we stood on the clean fringe of sand, the hush of the elements was even more apparent. Not a leaf moved in the thick humid heat, not a bird flew or animal moved. It seemed as though all Nature was waiting breathlessly for the opening of the cataclysm. But for the low rumble of the breakers, we might have trod another planet, some long dead world; and the thick sand, deadening our footsteps, gave us a peculiar disembodied sensation that was unpleasant in the extreme. It was Follansbee who broke the silence. "No good cooling our heels on this beach." he said. "Under the circumstances, I think it would be worth our while to do a little exploring. That track through the trees seems to suggest unlimited possibilities." He broke off and pointed to where a worn track wound its way through the undergrowth.

"At least," remarked the doctor, as we made our way toward it, "we cannot claim to be true Crusoes. Someone has used this path pretty frequently—and not so long ago, if we are to judge by its appearance."

"Animals—?" I suggested.

"Much too narrow," interjected Follansbee. "Then again, the beasts have no object in coming here; there is no water to drink, nothing to est and from my experience of animals, they generally shun the seabeach," he glanced at the dry rotted grass. "No, my sonny, that track was made by one thing only—a number of men walking in single file."

I looked blankly at the waste of matted undergrowth and stunted trees, "But where on earth did they go?" I asked.

"That," was the reply, "is what we are going to find out."

In single file we followed the circuitous path for over a mile, Follansbee leading, his grey eyes gleaming, the doctor next and I bringing up the rear. Through virgin greenery that walled us on either side, so thick that one seemed to be treading some matted corridor we went on; beneath wild and tangled growth through which the sickly light scarcely penetrated, over young lush leafage that overlay and half disguised the dank rottenness of the older vegetation, through which loathsome creeping things scuttled as we approached. things hideous and detestable to look upon.

The last portion of our journey was terrible. Here a fair-sized stream had become bogged by matted reeds and the spread of water was rapidly turning the surrounding country into a poisonous swamp. Clouds of insects hung over the black evil-smelling pools, some huge as wasps, with bodies of every conceivable hue and blend, some whose sting was death, others bred in the fever areas, carrying with them their dread legacy. The sibilant hum was disownable quite a distance away, and it sounded eerily out of place in that region of silence and decay.

Suddenly, with the abruptness that was almost startling, the forest ended and we saw ahead of us a flat plain. We were just about to step out on to the wide clearing, when Follansbee, who was leading, uttered a cry of amazement, stiffened and stood stock still. He was staring at some scene below him on the plain, and as we approached, he turned and finger on lip, pointed. Stepping quietly, we drew alongside him and I choked down the gasp that rose in my throat.

We were looking on a wide barren area of land, in the centre of which was a cluster of iron buildings. That they were tenanted was obvious by the thin trail of smoke that curled its way from the chimneys. One edifice, slightly isolated from the rest, was surrounded by a high wooden stockade, pierced at intervals by loopholes.

The Creatures of the Island

AS we watched, thunderstruck by our discovery, from one side of the stockade came a troupe of figures. There seemed no doubt that they were men. but such men as I have never before set eyes upon. They were of enormous stature, most of them being over eight feet in height. They moved with a peculiar lumbering gait, that was vaguely suggestive of something that I could not place. Their arms, swinging at their sides seemed absurdly out of proportion to their bodies, and the great hands clasped tightly upon an object that, at the distance looked like an axe.

Each wore a kind of khaki shirt and breaches, with leather leggings that reached from instep to knee. A sun helmet took the place of a hat and as one turned away from us, I noticed a peculiar irregular blotch upon the back of the shirt. At first, I took this to be some personal damage, but a further glance showed me that each wore a similar adornment. At the distance, however, it was impossible to distinguish the outline.

"By Gad," exclaimed Follansbee, as he unslung his glasses. "We seem to have stumbled on a modern Brobdingnag. Thank Heaven for that storm."

The Doctor was already examining the monsters, so after a scrutiny, the explorer passed his glasses to me. I adjusted the powerful lens to my sight, and the approaching creatures leapt into my field of vision.

If, at a distance, these creatures looked unprepossessing, they seemed doubly so at close quarters. The lens picked out every detail with horrifying clearness, the broad, hunched shoulders, the long muscular arms, covered with coarse black hair, the slouching movement. caused, I now perceived, by the ridiculously short handy legs. As one stopped to converse with his neighbour, he turned and the ragged blotch on his shirt took definite shape. I started again, thinking that my eyes were playing me tricks.

The shape was that of a five-clawed dragon, reared in the act of striking. It was either stamped or sewn on in black cloth.

But it was the features that drew the eye and held it in sheer horror, so hideously repulsive were they. The tiny head. with its wide slobbering mouth, the wicked red eyes and the flat coarse nostrils inspired one with a thrill of disgust and loathing. The low receding forehead and the forward position of the ears showed that, were they humans, they were of a very low scale of civilization.

"My God!" I heard Clovelly gasp. "Are they man or beast?"

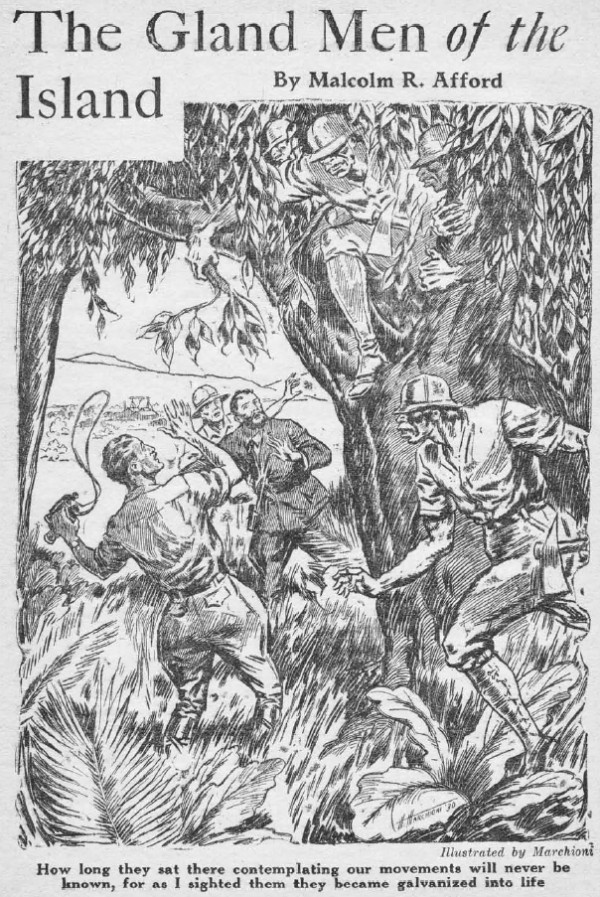

I opened my mouth to answer, when from behind there came a rustle of disturbed undergrowth. I swung around, but there was nothing to account for the sound, when, acting on some unknown impulse, I glanced up into the tangle of branches above. A cry of horror burst from my lips, for there above us, silent and motionless as the surrounding forest, crouched four of those hideous creatures that we had been watching. How long they had sat there, their bloodshot eyes contemplating our movements, will never be known, for as I sighted them, they became galvanized into life. With guttural screams they sprang upon us, and I was just about to run for my life, when one gathered me beneath his arm like a bundle of hay, and, with a curious wabbling stride, made for the walled-in building.

CHAPTER II

A Place of Terror

IN an incredibly short space of time, we had reached the high partition. Here the creatures paused and shouting something in the guttural tongue, pointed to the gate, then to his companions in the rear. In my awkward position, I was unable to glimpse the one to whom he spoke, but it was obviously the guardian of the portal, for even as I screwed my neck to breaking point, the obstacle swung hack, and we passed through.

I judged, by the stamp of the feet behind, that my colleagues were likewise captives, and by the sounds of struggle, that they were not submitting so tamely as I. Perhaps I was unfortunate in possessing a particularly irascible gaoler, for my puny efforts at escape had resulted in nothing more than a cuff across the face that nearly took my head off. Maybe it was just a gentle reminder that he would stand for no nonsense, but it served to quiet me beyond further resistance.

We traversed a slight dip and breasting the slope, came to the main residence. It was much more pretentious than the outbuildings, with neatly laid paths and flowerbeds. though the blooms could not be called healthy. Across the roof were looped slender wires, standing clear against the coppery sky, terminating in twin aerial poles. It strengthened my conviction that we had reached the headquarters of this amazing island.

Four wooden steps led us into a wide hall way, carpeted with rush mats, that strewed the floor at regular intervals. A number of doors, dimly discernible in the uncertain light, opened off this passage, whose extremity was lost in the prevailing gloom.

It was here that my guard at last set me down and turning, signed to his companions to do likewise. I smoothed my rumpled apparel into something approaching order and turning, beheld Follansbee, as imperturbable as ever, in the act of lighting a cigarette. Clovelly, seemed still stunned with amazement and he looked at me with eyes that hinted a thousand questions.

Before he had time to utter a word, one of the creatures wheeled around and disappeared into one of the rooms. As he opened the door, I became aware of a peculiar odor—sweet, sickly—that emanated from behind it. For just a second it eluded me, then as it grew stronger, I recognized it immediately—chloroform.

I glanced at Clovelly, and smiled wryly. He was sniffing the air like a thoroughbred, his professional instincts aroused. I noticed the slender white fingers quiver like the antennae of some giant insect, itching for the scalpel or the forceps.

Seeing my interest, he opened his mouth to speak, but what he meant to say will never be known. Suddenly, tearing jaggedly across the stillness, there came a horrifying shriek of some poor soul in mortal agony. Higher and higher it rose, in shrill cadence, then at the highest note it ceased abruptly, to die away in a gurgling mumble, then silence—thick—enveloping—sinister—

I am not easily frightened, but an icy horror gripped my heart. Clovelly was white to the lips and even Follansbee was shaken out of his customary equanimity. Our huge guardians seemed absolutely unmoved by the horrid experience, not an emotion was discernable upon their animal countenances, they were as devoid of expression as a rubber doll.

At that moment the door reopened and our guide appeared. Taking advantage of the diversion, I crossed to the half open door and essayed to peep inside. I was almost there when one of the creatures sprang forward and with an angry grunt, grasped my arm and with such force that I cried out. Our huge guide turned quickly and looking questioningly at his subordinate (as I took the other to be) fired a volley of unintelligible jargon at him. Suddenly the creature released me as though I had become red-hot and a look of something akin to deference crossed the bestial face. But I hardly noticed this, for my head was buzzing with a new discovery. The opening and shutting of the door had afforded me a momentary glimpse beyond—a fleeting vision of a modern operating theatre, the tables, instruments and assistants showing spotlessly clean in the bright artificial light.

One of the creatures crossed to a portion of the wall opposite the door and pressing on it, moved his hands in a curious circular manner.

The reason for this was plainly obvious the next moment, for there came the sound of a metallic click and a section of the wall swung back to reveal a door, set flush in the woodwork. With more haste than ceremony, we were thrust through this door, it clicked behind us—and for the first time since our capture, we were left alone.

BUT we had no desire to converse. We were struck silent by the extraordinary appearance of the singular apartment in which we found ourselves. I can close my eyes now, and recall every feature of that bizarre apartment as though it were yesterday, so indelibly are the details engraven on my mind.

It was circular in shape and lined with books from floor to ceiling, the reds and golds of the bindings reflecting the light from the mosaic shaded lamp that hung in the center of the room. Beneath this was a huge bowl of roses, the colours shading from one extreme to the other. Some there were so dark as to appear almost black, to vivid scarlet and flaming yellow, to others so delicately tinted as to truly rival the shy blush of the maiden. They filled the room with a heavy, exotic perfume and as I gazed, one of the flowers, fullblown in that superheated atmosphere, burst slowly and the creamy petals drifted slowly—one by one—lightly as thistledown—onto the rich red carpet on the floor.

Behind this great bouquet was a square block of perfectly grained black marble, flanked on either side by fantastically wrought incense burners. Poised on the marble base was a five-clawed dragon, in the act of striking, carved from solid ivory with the meticulous care that characterizes the oriental artist. So cleverly was it wrought that the object seemed to possess a personality that was both fascinating, yet repellent. It was wickedly beautiful in its own way, and it recalled to me similar emotions when I had first handled a Renaissance stiletto.

Directly opposite the carving, the books ended abruptly, to recommence at an interval of about three feet wide. Across the aperture was hung a heavy plush curtain, crimson with golden edging, and worked with poppies and roses. It fell in heavy folds that hung motionless in the still air, exuding an influence of the obscene and the unmentionable.

I turned and something caused me to rub my eyes. Of the door we had entered, there was no sign. Save for the curtained aperture, the book-lined walls continued in an unbroken line around the room. Hardly able to believe the evidence of my own eyes, I walked up and ran my fingers over them. My hand encountered bindings—red—gold—that winked mockingly in the vari-coloured radiance.

The choice of hooks in themselves was remarkable. The titles covered a wide range from the transcendental and metaphysical and all manner of works on the processes and oddities of the human thought seemed to be assembled there. They ranged from the days of black magic to psycho-therapeutics of the modern analytical school. There were volumes by Zaasman and Jung, together with other foreign scientists on the morbid phenomena of the brain.

Interested in spite of myself, I took down one book in German, a tongue with which I am fairly conversant, but after a hurried glance returned it hastily to its position.

It was a study of Dementia Praecox and its plates of naked German lunatics almost turned my stomach, quite unused as I was to the German scientific treatment 'of the more repellent disorders of life.

At the end of the highest row were a number of volumes touching on the influence of suggestion on the human mind. They ranged from the early investigations of Bertrand and of James Braid to the more recent studies of auto-suggestion by Coue and other modern French writers in this line of thought.

"By Jove, Follansbee," the doctor's softly spoken remark brought me round like a shot. "You wanted adventure, you craved something different — well, you've got it, with a vengeance."

A Narrow Escape

THE big explorer shrugged his shoulders. "There are more things in Heaven and Earth, my dear Horatio—," he quoted. "We seem to have stumbled fairly into the latest six shilling sensationalism." He glanced at the watch on his wrist, "By the Lord Harry, it's almost ten o'clock. I could tackle the proverbial leg of an iron pot, I'm that peckish. I sincerely hope someone puts in an appearance shortly," he broke off and glanced round the room. "Who owns this musical comedy apartment, anyway?"

The doctor paced the room, his hands locked behind his back. "Do you know," he said, as he drew abreast of us, "I rather fancy that we are on the eve of a momentous discovery. Taking the curious events in their sequence, we have the finding of the Islands, the well-worn path through the woods of an apparently uninhabited island and our discovery of the giant creatures that eventually captured us. Add to that the fact that there is installed here something in the form of an operating theatre—so much is plain by the use of chloroform—and we are left to arrive at only one conclusion."

"Why," I broke in, "Behind that door from whence the ether fumes emanated, is an operating theatre, up-to-date and modern in every respect. Though I caught just a glimpse as the door opened, I recognized the Newington naphtha flares, and they have yet to be installed in the Prince's Hospital. Evidently, whoever uses the room insists on every known appliance."

Clovelly nodded absently. "Exactly. It bears out my theory that before we leave this island, we are going to learn that science, in the hands of the unscrupulous, can do quite so much harm as it can do good." He turned to me, "You, Huxley, with your medical knowledge, can you not glimpse at what is taking place here?"

I shook my head and coloured slightly. "I can perceive nothing more than is apparent to all of us. In some manner, the ruler or owner of this island has possessed himself of some secret formula for the making of supermen. This he does by some delicate operation, for the elaborately equipped operating room and the modern Blood Filter are both necessary in the course of the metamorphosis."

"And have you no idea of how this transformation is effected?"

"Not the slightest, but I know enough to be aware that he has a tremendous power for good or ill. Just how he intends to use it is a matter for conjecture."

The doctor turned to Follansbee. but that gentleman was gazing intently at the curtained-off aperture. He closed his eyes tight and shook his head. "Either I'm going clean blind batty or my eyes have developed the shakes, but I'm certain that I saw that curtain move. I was just standing here when—look, there now, do you see it?" be broke off abruptly and pointed a finger at the gentle moving cloth.

We stared as if fascinated at the slowly writhing folds, as it twisted and coiled itself into thick pleats, to belly out like a sail in the sea breeze and then resolve into tiny undulations that rippled across the crimson surface. But' the culmination came when from behind it there arose a peculiar coughing grunt, followed by a gasp of someone or something struggling for breath.

"What fresh deviltry is this?" muttered the explorer uneasily. He raised his voice.

"Anyone there?" he called.

There was no answer, but I for one was hardly surprised. It was not enough for Follansbee, though. He squared his broad shoulders and clenched his fists. "I say," he called again, "is anyone there behind that curtain?"

But the silence of the weird circular chamber was unbroken. The curtains were motionless now. Another rose bloom, a flower almost dead black, fell to pieces. Almost mechanically, I counted the falling petals—ones—two—three.

The big watcher paused just one second, then with chin jutting ominously, he strode toward the aperture. I could not but admire the stark courage of the man, facing unarmed a danger, increased a thousandfold because of its indefinable quality. Though my heart beat suspiciously fast, I stepped up beside him and we were almost to the curtain when an unlooked-for contingency occurred.

"I would advise you, gentlemen, to leave things that do not concern you, untouched. The consequences of spying are sometimes painful in the extreme."

THE voice was suave and modulated, but it possessed the quality of a revolver shot, it could not have startled us more. We whirled as if stung and gazed with wide eyes at the author.

He was standing a little in rear of Dr. Clovelly, and his manner of entry was a matter for conjecture. Certainly none of us had heard him, but as he was standing where I presumed the secret entrance to be situated. I judged that he had achieved egress in like manner.

It needed only a second's scrutiny to place the man as an Oriental, but he was clothed in a neat fitting grey suit and shod with smart, square-toed patent shoes. His skin was smooth and butter-yellow and a pair of large tortoise-shell glasses bridge his nose, the huge pebbles making the eyes absurdly out of proportion with the rest of the countenance. He wore his hair long and brushed back off a high intellectual forehead. He spoke with just a slightest trace of accent, a metallic emunciation of the consonant "r"—a trait which characterises even the most educated of Chinamen.

"I trust, gentlemen, that you will excuse the somewhat rough handling. Strangers are not welcome on the island of Ho Ming, especially white strangers."

As the insolent voice ceased, a thin ironical smile curved the thin lips, revealing two rows of yellow teeth. But there was no humour in the narrow-lidded, purple-black eyes, for in their inky depths there lurked the cruel passionless look of one who had gazed too lung on agony and suffering to feel the sorrow and pity of it all. They reminded me of the loathsome orbs of a hooded cobra.

Follansbee was first to recover from his surprise. "If we are not asking too much," he asked quietly, "May I enquire just where we are and what relation you bear to all this," he waved his hand around the bizarre apartment.

With all the slow dignity of his race, the Chinaman raised his hand. "I will explain in my own time," he said blandly. "It is I who give orders now and you will obey—" He smiled at the angry Follansbee—"No! Then steps will be taken to make you obey. We of Hankow have many methods of curing obstinancy."

Dr. Clovelly started forward. "We are British subjects," he cried. "If you harm us in any manner, the government will blow your island to Glory and you will end your career with a rope around your neck."

The Chinaman bowed and spread his hands. "If it eases you to entertain such delusions, Dr. Clovelly, by all means do so. But you have evidently forgotten the necessity of communicating your unfortunate position to your Government."

"How do you know my name?"

"I know many things, for I am the chosen ruler of the People of the Ming Dragon. You have arrived at a most opportune moment—" the Oriental broke off abruptly— "Gentleman, I have a proposition to put before you."

He walked over to the black marble dais and seated himself thereon. For a moment he sat thus, seeming deep in thought, then he raised his eyes and glanced at each of as in turn.

"Now," he began, "I want you to hold no delusions as to your position on this island. You are my prisoners, for me to do with you as I whim. But you are all men who have achieved some fame in your respective professions and I have no desire to rob the world of your talents. So—I offer this truce."

He turned in his seat and directed a long slender finger at the doctor. "I know you, Clovelly, as one of the greatest of living authorities on the gland-grafting treatment. Your studies with Steinach in Vienna, when you unearthed the Cod Bone method proved to me that you had the business of glanding and rejuvenation at your fingertips. Mr. James Huxley, your assistant, needs no introduction to me, nor does your friend, Mr. Follansbee.

"You have, no doubt, been rightfully bewildered over the strange creatures that inhabit this place, hesitating to categorise them as either man or beast. Let me set your mind at rest, and inform you that they are neither and yet both. That is to say, they possess the characteristics both animal and human, because they are of a scale of civilization that is intermediate. They eat. walk, talk and work, possess the strength of ten men, live to an almost prodigious age, and lastly, possess a certain immunity from sickness and disease. They are my Gland Men and are the latest triumph of modern science."

The monotonous tones ceased and the speaker, taking from his pocket an inlaid case. extracted a cigarette. I blinked my eyes and breathed hard, thoroughly convinced that I was mad or dreaming. The coloured shade stained the floor with its dancing hues, the rose-scented air seemed charged with the dominant personality of the owner. The scratch of a match recalled me and I saw the smoke curl through the nostrils of the Oriental, as he lay back and surveyed us with his narrow oblique eyes lowered to mere slits.

CHAPTER III

A Gigantic Scheme

"NOW, gentlemen, behind this is a story of patience and attention to detail that can only be achieved by one in search of an ideal. Up on the slopes of the White Headed Mountain, on the Western border of Tibet, there stands a Lamasery known as the 'Brothers of the Golden Khan'. It is the holy of holies, this desolate edifice, for in its sacred precincts there dwells the Most Illustrious Deity, the Grand Lama Dalai. He is a beautiful youth, with skin as soft as a maiden and limbs muscular and symmetrical. Though he has attained the distinguished age of two hundred years, he has the appearance of an unsullied youth, a fit spectacle for the thousands of devout Chinamen who yearly visited the shrine, leaving it richer by gifts and money.

"Now, my father entered that Lamasery as a youth, not because of any religious urgings, but because he regarded the permanent youth of their Deity to he nothing more than a gigantic hoax to attract money and notoriety to their shrine. He knew that the priests must possess some miraculous secret of preserving eternal youth and he meant to obtain that formula, cost what it may. That the task was no sinecure was obvious, but he had the patience and perseverance that only one of the East can inherit.

"For forty long years, my father lived with the priests, and he was just on the point of achieving his life's desire. when he was betrayed by' a treacherous servant. He was caught and after a year of endless torture eventually made his escape. He fled to Hankow, where I was studying surgery and delivered into my hands the sacred tomes containing the great secret formula. Further information I could not receive, for amongst other things, the Lama priests had torn my father's tongue from his mouth, thus making him dumb forever.

"Then followed a reign of terror for us. My father and I flew from plane to place, but nowhere could we escape the watchful eye of the vengeful priests, who, by that time, had discovered the missing volumes. At length, I evolved n plan by which we would be free from further persecution. I personally sought an interview with the Great Emperor Dragon, the great Shem Sing, and laid my plans before him. He was delighted with the idea, and not only gave orders that I should be protected, but also agreed to finance the scheme in view.

"One of the chapters in the book dealt extensively with that branch of anatomy known as the Endocrine Glands. As you gentlemen are aware, this is but a newly discovered phase of surgery, but to the Holy Brothers, it had been old knowledge. There is nothing in this earth so strange and fantastic as the history of those obscure bodily organs that mean more than life to us.

"Amongst other things, the two most frequently mentioned were the thyroid, that shield-like gland astride our Adam's apple and the pituitary, hanging from the base of our brain by a hollow stem. The pituitary controls our growth, but the thyroid controls everything that makes our life worth while.

"Children with deficient thyroids—from atrophy, removal or injury—become things horrible to look upon, glibbering idiotic dwarfs—heavy featured and twisted in body. Cretins they are called, for they never metamorphose into normal adults. Hence the importance of the obscure organ.

"But the Brethren experimented on aquatic larvae. They caught a tadpole and removed its thyroid. It never became a frog, but remained a tadpole for the remainder of its existence. On the other hand, they gorged a tadpole with thyroxin, and almost immediately it changed to a frog. I say changed, gentlemen, not grew— because the tadpole did not grow. The frog, fully developed, remained only as large as a tadpole. Thyroxin feeding produces two results, it hastens metamorphosis, but retards growth.

"With this information, my father and myself started out upon our momentous scheme. We obtained the thyroid from an ape and transferred it to that of a three-months-old baby. Almost immediately the child began to exhibit simian characteristics—then the body began to alter shape. But the child grew no larger than the day the gland was transferred and it was to overcome this difficulty that we set ourselves.

"Now the growth, or pituitary gland is not a vital organ, but a normal gland is essential to normal life. An operation on the pituitary is enormously difficult—for one thing, it is only as big as the tip of the little finger and it is so near the centre of the head that it is next to impossible to localize. But we finally overcame this difficulty and all was ready for the final experiment.

"THIS was the scheme in mind. If a grafted thyroid could transform a child to an ape, would it not be possible to transplant the glands of an anthropoid to that of a growing human? An operation on the pituitary would overcome the difference in growth and the finished product would possess the strength and power of an anthropoid and the intelligence and appearance of a human being.

"Such was the scheme that occurred to me. Luckily I was possessed of twelve sisters, and each, in turn gave their lives for science. Still we were unsuccessful, the creatures of our experiments being things hideous and fearful to look upon, that were killed as soon as tested. Then our faithful servants professed themselves willing to give their lives. Three there were and by a strange freak of Fate, it was the last attempt that was successful. We achieved a huge beast, such as you see here today, and it was this creature that we took to the Emperor as proof of our good faith. Then we outlined to him our momentous scheme.

"What a great thing it would he for our decadent empire could we but manufacture an army of these Gland Men. They would he immune from hurts and outlive the strongest of soldiers. Again, they would seek for nothing in return, fighting but to appease their brutal instincts. With an army such as these, we could wipe the entire White Race from the world and restore China to her rightful position as Mistress of the World. The magnificence of the scheme fairly dazzled me, such prodigious possibilities did it possess.

"Here you see the great scheme in embryo. Thanks to the magnificent generosity of the Emperor, we have unlimited facilities for the great scheme in progress."

Once more he paused, and the hard black eyes. alight with the fire of fanaticism, gleamed and sparkled like wet anthracite coal. He leaned forward and waved a thin yellow hand in our direction.

"White men," he said, "Here is an undoubted truth. In a decade this colony will be a serious menace to your white civilization—and in fifty years we will sweep you off the earth. China will return to her rightful position, and the world will bow down to the despised Chinaman."

"Really," Follanshee's coolness was superb, "And if we whites are considered such a nonentity, why expound to such a length to us?"

The light died out of the Oriental's countenance and the eyes narrowed perceptibly. He inhaled deeply on his cigarette and as the smoke curled through the flat nostrils, the pungent odour hung in wisps on the heavily scented air.

"My Gland Men," he murmured, so softly that the purring voice was scarcely heard, "lack but two things. One—the method of human speech, and the other—of paramount importance—is their sexlessness. It is upon you gentlemen that I rely for the rectification of those surgical errors."

Dr. Clovelly took a step forward. "And if we refuse?"

The Oriental shrugged his shoulders. "I have just attended to two operations this morning," he replied meaningly, "and in the advent of your refusal, I will attend three more tomorrow morning."

"Do you mean that you operate here?"

"Certainly. Why not? We have every facility of modern science, and a laboratory that is the last word in the up-to-date."

"But—but—" babbled Dr. Clovelly, amazedly, "Your supplies—and chemicals."

Ho Ming gave an upward gesture of his hands. "Wireless," he explained. "A call to our base will bring a ship load of supplies within a few days. That is what has cut that path through the undergrowth."

"But your—er—patients do not recover immediately. You must have a hospital, or something of the kind?"

"If you consent to my proposition, Dr. Clovelly, I will make arrangements for you to be shown over my island as soon as it is possible."

CLOVELLY spread his hands helplessly. "Under the circumstances," he acquiesced, "we can do nothing but submit. But you must promise that we meet with no treachery."

The Chinaman inclined his head. "Have no fear of that," he assured us. "And now I shall show you around. You shall see that this is no wild dream of mine. It has taken years to accrue the knowledge and effects, but it is all to the one purpose."

With his quick, silent walk, he crossed over to the crimson curtain and pausing before it, spoke for some moments in the pure liquid Ho Man dialect. From inside there came a rustle of silken garments and suddenly, as we listened, there arose again that evil voiceless murmuring that we had heard on the previous occasion. Ho Ming turned to and waved a hand in the direction of the curtained aperture.

"My illustrious Father—The Great Bald One—The Learned Wong K'tai, who first wrested the priceless formula from the Lama pigs and to whose patience and saintly perseverance, this island owes its existence."

So that was the solution of the peculiar sounds, and I was about to pace forward, when Ho Ming, with a peculiar smile held out a restraining arm. He then picked up a slim ivory wand, and with a quick movement stabbed it at the curtain. Immediately there came a Szz and a bright flash as something shot through the air. but so quick—so unexpected—was the whole action that I did not have time to glimpse the object. The next moment the Chinaman, with a bland smile, moved forward and held aside the curtains.

The room into which we looked could not have been more than six foot square, but screened on all sides as it was by rich hangings, it gave the illusion of depths that was very cleverly carried out. The black velvet hangings were worked with a be-wildering array of birds and flowers, in colours both rare and wonderful. Scarlet parrots, blue peacocks were entwined will! crimson poppies and roses of every shade and hue. Gaudy though it undoubtedly was, there was nothing in it to offend the eye, for the colours were blended with the skill of an expert.

In the center of the room, in a huge chair that almost enveloped the slight form, sat the oldest Chinaman I have ever set eyes on. He was thin to emaciation and the rich purple robe he wore hung in folds about his skinny frame. His head, bowed slightly with the weight of years, was as bald as an egg and the long beard that hung from his chin was white as the driven snow. The face was seamed with a thousand wrinkles and only the beady eyes, sunk deep in the lined countenance, gave a hint of vitality. He sat motionless, like some grotesque idol, a fit parent to this place of sinister secrets.

Ho Ming entered the room and pausing before the chair, fell upon his knees. For some moments, there was a silence, then slowly, like one in a trance, one claw-like hand, yellow as ivory, was raised in salute. For a second it remained poised, then, as though its owner lacked strength to hold it in place, it fell limply back onto the chair. Ho Ming rose to his feet.

"The great One salutes you, and wishes you well. Gentlemen, you may consider yourselves doubly honoured."

He recrossed the room and as he made his way through the doorway, the curtain dropped behind him. Synonymous with it came the swish and the flash, and the Oriental with quick movement touched a portion of the woodwork. immediately the object came to rest and for the first time we saw it. It was a blade, some six inches wide and the width of the doorway, a blade razor-edged and weighted at the top. It ran down between the doorposts on a concealed wire, very much on the principle of the French device, the guillotine, at an almost incredible speed. The Oriental released it, and it disappeared into a slot in the floor.

"Quite Chinese," he purred. "Borrowed from the palaces of the Emperors. By the way," he turned to Follansbee, "It was as well that I arrived when I did, this morning, for had you stepped across the threshold, you would have been cleft in half." He walked to the book-lined wall and moved his hands in the circular manner we had noticed before. With a click of concealed machinery, the section swung back, and we filed into the dimly lit passage. "Now," our guide cautioned us, "Keep close to me and offer no resistance, no matter what happens."

CHAPTER IV

Awaiting the Storm

THE contrast between the brightly lit room and the semidarkness of the passage was so great that for some moments I could perceive nothing, far less distinguish any objects. The luminous dial of my watch told me that it was just past the noon hour and I could not but help reflecting that we had certainly spent a crowded hour. It seemed incredible that all our strange adventures had been compassed in such a short space of time; already we seemed to have spent months on the island, and England and Prince Alfred's Hospital seemed very far away.

Gradually, as my eyes became accustomed to the light, I made out the various doors leading from the strange apartment. The Oriental Ho Ming took the lead and we others trailed behind him. At the end of the passage he paused before a door.

"This," our guide explained with a gesture, "is the laboratory. Here it is that the serum is compounded that speeds up our workers and helps them to overcome the laziness that they inherit from the anthropoid side of their nature. Adrenin, obtained as you know, from the adrenals near the kidneys, forms a large percentage of the serum. Adrenin is the greatest and most natural stimulant known to mankind."

He threw open the door and we surveyed a long low room, with wooden benches running the entire length. Upon these were placed a heterogeneous collection of scientific instruments—microscopes, galvanometers and centrifuges. Everything was scrupulously clean and three assistants in spotless overalls hovered silently about the room. Ho Ming gave a sharp order and immediately one of the men crossed to the bench and procured a lest tube half-lull of some dirty brown liquid. This he placed in his caster's hand.

"This is the inoculation serum," explained the Chinaman. "You must understand that the ape-glands are incredibly strong and that if left to themselves, must ultimately reduce their owner to a stale of bestial idiocy. To prevent this, an injection of the serum is necessary at least once a week. The result of the adrenin in the blood is at once apparent. It speeds up the sluggish heart beat, drives fatigue from the muscles, and prepares the body for emergency function. A very simple formula", he returned the tube to its place as he spoke, "I discovered it something like two years ago."

He closed the door and we retraced our steps along the passage. "Removal of the thyroids and parathyroids necessitates cutting away certain portions of the larynx" he was explaining to the doctor. We tried cutting through the windpipe into the cricoid cartilage—" and he rambled away into the realms of surgery with Clovelly listening delighted and entranced.

I took advantage of his immersion to drop back with Follansbee. "What do you think of it all, anyway?" I muttered.

He surveyed me for a moment, his grey eyes lighted humorously. "Two things strike me with perturbing force. One is that our Oriental friend is a loyal fanatic and means every word he says. The other is that we are in the very devil of a hole and I don't mind telling you young fellow, that just at present, I tail to see the tiniest loophole of escape."

"Do you think the man is mad?" I murmured, having digested the somewhat disturbing statement of the other.

Follansbee shrugged his shoulders—"He may be", he assented. "There is no doubt that he is clever—and cleverness and insanity often go hand in hand."

I glanced to where the two men were holding excited converse. "I do believe that Dr. Clovelly is really enjoying himself," I remarked softly. "He's hanging on to the Chinaman's words as though they were pearls of great price."

The other man smiled, a trifle grimly. "I think that the doctor will be quite safe," he returned. "It's little us that's worrying this child. You see, we may be guests of honor for as long as the childish vanity of our hosts continues, but one day, they'll run short of raw material, and then—" he made an expressive gesture.

I was about to reply, when the Chinaman paused with his hand on another door. He regarded us suspiciously as we walked up together and his voice was as sweet as honey as he observed.

"Do not linger behind, my friends," he glanced over his shoulder as he spoke. "There are many strange things in the abode of Ho Ming. Fingers that claw and grasp, hands that tear and break. It is very foolish to stray behind."

WITH that he pushed the door and as it swung open, We glimpsed a well-lighted apartment, with twin rows of beds running along either side. Around two of the nearest, white screens were placed and from behind one of these a faint moaning emanated. The air was charged with the acrid tang of carbolic and as before, everything spoke of scrupulous attention to detail.

"My hospital," it was explained. "My patients come here from the operating tables and from here they emerge to the outbuildings, to do their allotted share among their fellows. There is no intervening period, which we know as convalescence. A week in hospital is long enough for the newly grafted gland to function. Then sunlight, fresh air and hard work do the rest. It is amazingly simple."

"But," I interpolated, "Where do you get your material to work on? It must come rather hard to find men willing to sacrifice themselves to this sort of Roman holiday."

"Convicts from the State Prisons furnish us with much work," was the cold reply. "Murderers, servants, and occasionally a few are pressed into service by my assistants, who form a modern equivalent to your old-time press-gang."

I grinned a trifle rudely. "Bang goes your dream of world revolution," I returned, "if that is how you progress. After weeding your prisons clear of undesirable characters the magnum opus will languish and finally die of insufficient means of support.

Ho Ming turned his unfathomable black eyes upon me. "Presumptous fool," he said, coldly. "China now possesses an army of six thousand men, drilled and perfect in the art of war. As soon as circumstances will allow sufficient serum will be despatched and under the treatment of my assistants, every soldier will become a Gland Man. After that every man who enters the army will be likewise glanded, and in time we shall possess an entire army of these supermen."

I raised no more questions, for if the Oriental was insane, there was assuredly method in his madness. In fact the gigantic scheme was too complete, and for the first time, the true meaning of this man's insane dream chilled me with its appalling possibilities. The doctor's voice broke in on my reflections.

"And are all your operations successful?" he asked. "In such a delicate business as this, one would think the failures outweighed the successes."

Ho Ming looked at the speaker, his eyes alight with a peculiar gleam. "Ya," he said, slowly, "we do have failures, in spite of our precautions. Before you see them, I warn you—they are not pretty to look upon."

He led the way through a side door and we found ourselves once more in the day light. The weather had changed completely since our sojourn inside. The sky, brassy before, was now almost clear, the hard blue sullied by a thick band of black clouds that spread themselves like some ebon canopy across the eastern sky. Little puffs of wind stirred the dust and dried leaves at our feet, whirling them into the blue. The atmosphere was thick and heavy, so heavy indeed, that some difficulty was experienced in breathing, and the sun poured down with a fierce heat that was almost unbearable. The silence was broken intermittently by a low sibilant hum.

Follansbee glanced curiously around him. "It's coming," he said appreciatively, "it's coming, and by Heaven, I pity this place if it strikes it."

We skirted the main building and passed through the high wooden stockade till we reached the outbuildings. Some little way further on, we could perceive a number of the queer inhabitants engaged in erecting a new structure. They swung the huge tree-trunks as though they were light sticks and in an amazingly short time, the central framework was raised.

We passed a long building, constructed of rough hewn timbers, containing a number of small cubicles. Each separate room had its neatly folded mattress and shining eating utensils. The place contained no comforts whatever—just the bare necessities of living, and was obviously the domestic quarters of the strange beings that Ho Ming called his Gland Men.

The Revenge of Nature

A PECULIAR smell win predominant here increasing in strength as we made our way onward. Everyone is 'familiar with the loathsome. animal smell, that is prevalent wherever beasts are incarcerated. It emanated from a tiny hillock, built over an underground cellar. A gate led us down about a dozen steps cut in the earth and brought us up before a massive iron door, with a barred grating set in the top. The snapping and snarling of animals came clearly to our ears, and the words of the Oriental "they are not good to look upon" took on fresh significance.

The Chinaman, who was in the lead, stepped forward and sliding back the grating motioned me up. I peered in, scarcely knowing what to expect, and hardly had I taken one brief glimpse when I recoiled was a gap of horror. Even Dante, in hid journey through the innermost Hells, could scarcely have viewed such horrible creatures as haunted that underground pit.

There must have been over a dozen of them—loathsome—terrible. Some twisted beyond any semblance of recognition, others with stunted bodies and bloated appendages growing on various parts of their anatomy. They stood silent as I glimpsed them, looking at me mildly with their bloodshot eyes, gesticulating with their crooked, shrunken limbs. But the crowning horror was the undeniable fact that once these things had been men, even as you and I, living—listing—breathing.

As I stumbled up the stairs, sick with horror. I was joined by the Oriental, who stood watching me with a sardonic smile on his lips. I did not speak, but stood there, drinking in the thick air in thirsty gulps. And then suddenly it happened.

It began by the sunlight fading, and glancing up, I saw that the monstrous black cloud had overshadowed almost all the sky, leaving only a portion over the sea, that glowed eerily with an uncanny elfin radiance. The low intermittent humming had risen in cadence and was coming nearer every second. A patter of feet made me swing round, and there, his face white with terror, was one of the overalled assistants. He stepped up to the Chinaman and poured forth a string of incoherent language, that for a moment. eluded even his countryman. Then I saw Ho Ming's face turn a sickly green, his eyes protruded. and he barked back a question into the other's face, and I distinctly heard the name K'tai. Then without a word, Ho Ming turned on his heel and, side by side, the two raced for the main building as fast as they could move, leaving me standing wide-eyed with amazement.

A moment later I was joined by my companions, and to them I explained the sudden departure of the Chinaman. As I spoke, several big drops of rain commenced to fall, and Dr. Clovelly glanced anxiously at the sky. "Hallo!" he ejaculated, "Here's that storm that you promised us, Follansbee."

But that gentleman jumped to his feet as though he had been stung. "Storm be damned," he exclaimed, "That 'storm' is a number one size typhoon, and it is heading this way. I give it five seconds to strike the island."

THE terrific upheaval of Nature lasted three hours, and to us adventurers, crouched in the groaning swaying forest, it was the final denouncment of our astounding adventures on the Island of the Gland Men. Towards evening the hurricane dropped, but the rain poured down with unbridled fury, sweeping and lashing the vegetation before it. Such a deluge it is almost impossible to describe, rather it was as though the skies had opened and the seven seas poured their waters through the gap. Even in the thick of the matted vegetation, we were drenched to the skin, and it was almost dark when we eventually crawled forth from our shelter and took our last look at the island. The downpour had abated somewhat, but it still swept in our faces with the sting of a whip-lash, and at length, Wet, half-blinded and weighed down by the weight of our sodden garments, we gazed at what had once been the realization of a fanatic's dream.

Such a scene of destruction and chaos beggars description. The sturdy buildings had been swept away like match boxes before a summer breeze. The heaps of wood and iron were still faintly smouldering and when I remembered the volatile chemicals that were ranged along the shelves, I perceived that combustion must have wrecked quite as many of the edifices as the howling typhoon.

There was the hall-erected framework, now splintered and scattered. There loo, the poor dumb beasts that had once been men. The cataclysm had burst upon them before their bestial minds had time to realize its significance. The rain swept mercilessly down on the inanimate hairy bodies, as though gloating in its power over mere mortals.

The high stockade was, by some miracle, still standing in places. In other places it gaped open, showing the destruction within the walls. Here the bodies were piled, corpses torn, scratched and bitten, telling of the panic that must have enveloped the community, as it fought for freedom. I wondered if any of the hideous denizens of the underground pit had escaped, but a glance assured me. The ruins of the main building were piled feet high over the vault of horror.

Of Ho Ming there was no sign. It was impossible that he had lived through the chaos that had enveloped the Island, but it was hardly probable that everyone was dead. We. to be sure, only owed our lives to our sheltered positions, but there might have been others.

The Island must have been situated in the very centre of the catastrophe, otherwise there was no manner of accounting for the terrible amount of damage. It seemed strange—ironical—that the toil and labour of a decade should thus be destroyed in a few hours. The Chinaman's scheme had been a marvel of completeness, but the best-laid plans-.

We retraced our steps in silence, each one a little chastened by the tragedy that we had passed through. We were nearly to the beach when I put the question.

"What made the Chinaman rush away like he did?" I asked Follansbee. "He turned a sickly colour and went for his life."

"Didn't you say that you heard his father's name mentioned?" the big man asked. "Well, ills obvious that the servant told him of the coming storm and he rushed off to comfort and protect his lather. The paternal reverence is very strongly developed in the Oriental races, and he evidently cared for nothing as long as his father was safe. Recollect that all he had was made possible by the sacrifice of his parents."

We had reached the electric launch, beached high and dry where we had left it. As we swung it round, I voiced the unspoken question of the trio.

"Will anyone believe us?" I ruminated, "when we tell them where we have been and what we have seen? I very much doubt that I would, were a person to recount to me the—"

I broke off suddenly. The ground beneath our feet was shivering and heaving, and for a moment, I doubted the evidence of my eyes. The next moment it was still again, and I was about to ridicule the idea when Follansbee grasped me by the arm.

"Did you feel that?" he said, "For God's sake, get that launch on the water. There is going to be a lot of funny things happen here before long. Come on."

In less than twenty minutes we were in sight of the ship once more and then it was that Follansbee made the final remark.

"Not a word about our adventures," he warned, "I'll get Sparks to radio Port Moresby for a destroyer to clean up that Island. I suppose that it will be necessary to give them a bare outline."

And I turned to see the foreshore of the Island, still brooding and sinister, disappearing into the tropical night.

There is but one incident worth while recording, however, and it tool: the form of a radiogram that Follansbee received after his detailing the story to the Naval Authorities at Port Moresby.

"Searched water for some time in latitude given. Find no trace of Island. Suspect some elaborate hoax. Am temporarily dropping matter."

What is the explanation of that message. Can it be, as Follansbee informed me, that Ho Ming made his headquarters on one of these roving islands that are never in the same place for any length of time? Were the mysterious tremors we felt forerunners of another upheaval?

And if that is so, I often pause to think of the misguided genius that lies fathoms deep in the ocean and the terrible formula that must remain a secret till the sea gives up its dead.

THE END