Help via Ko-Fi

IT often happens that some of the great advantages that men expect to gain by gathering together in large cities turn out finally to be boomerangs. People collect into communities of hundreds of thousands and millions to take advantage of mutual economic and social advantages; and give up their own identity so that they may have the strength of the whole group. They are thus better protected against disease and poverty. These of course are the assumptions. But when trouble does come to a large city, it comes as a great disaster. Epidemics of diseases, great fires, outbursts of crime, etc. are all prices that we must pay to enjoy city life.

Think how easy it would be to spread abroad in our great cities a contagious germ to decimate thousands! Or how easy it might be to poison our water supply. Suppose theta great evil force wished to strike at our national life, and he started with the large cities. How might he go about it? Dr. Keller answers this question in this story full of his un-tragedy!

"THERE was a Chinaman in town today," announced William Buzzard, the Recorder of Deeds of Monroe County. He slowly placed his feet on top of his desk and started to blow smoke rings through the dead air of the closed office.

The County Treasurer laughed at him.

"What are you trying to do, Bill? Kid me? Think I never took my collars to the laundryman? Long as I can remember there has always been a Chink in town."

"This was not that kind of a Chinaman," slowly retorted Buzzard, talking out of one corner of his mouth.

"That's news to me. Is there more than one kind of Chink?"

"You would think so if you ever saw a real one. This one today was only a yellow boy, but, believe me, Han-kins, he had class. He drove here in a swell car and he had on the very latest in New York haberdashery, and I ought to know, because I just had a chance to read an article called, What the well dressed man will wear in 1935. He gave me this elegant piece of tobacco I am smoking.

"You will observe from the smell that it is no cheap five center. And then, to show you that I know what I am talking about when I say that he had class, he had me record a deed for him which shows that he had just paid four hundred thousand dollars for the four thousand acres of land around Resica."

"I'm dreaming! Wake me up!" murmured the County Treasurer. "You don't mean to tell me that the New York people have finally unloaded that Resica land?"

"I do. And I remember when I could have bought that land for five dollars an acre."

"All I have to say," remarked Peter Han-kins, "is that they must have put the deal over when the Chink was asleep. I thought those yellow boys were smart."

"They are smart," nodded Buzzard. "Smart as the Old Boy himself. I have read about them and seen moving pictures about them until I almost feel that they are smarter than the average white man. I bet that this Chinaman had some reason for wanting that land at Resica. Perhaps he would have been willing to give more if the New Yorkers had held off a while. You will find out some day. He has something up his sleeve about that land. He knows something about it that makes him want to own it—oil or something like that. And I could have bought that land for five an acre."

A few days after the deed for the Resica land bad been recorded a well-dressed Chinaman wandered casually into the main offices of the Highway Department in Harrisburg, Pa. There was a slight difficulty in finding the correct official to talk to, but at last he was in conference with a politician, who was smoking as fine a cigar as it had ever been his good fortune to light. With such a present in his mouth, it was impossible to be anything but polite to the donor; so, he asked, in his best manner, as he gazed at the visiting card in his hand:

"What can I do for you, Mr. Wand Foo?"

"I trust that my request is a very simple one," began the Chinaman, opening a map and spreading it out on the table. "Condescend to gaze upon this map of Monroe County. Here is a little place called Marshall Falls. From it a road runs through a thinly populated country and finally it ends up in Pike County, in what is called the deer country. This road runs—through a four thousand acre tract of land, recently purchased by my associates. We regret the existence of this road, and desire your honor able aid in closing it."

The politician looked at the map closely.

"Where's your land?" he demanded.

"Around a place called Resica."

"Hemmm! There is a good iron bridge there."

"Exactly. The existence of the bridge annoys us."

"Well, it's there, isn't it?" asked the politician sharply. He was beginning to be slightly annoyed. "You knew that the road was there and you knew the bridge was there when you bought the land, didn't you? We cannot close roads and tear down bridges just to please people. How do you suppose the hunters would get up to the deer country?"

"If you look at the road carefully, you will see that there is another road that could be used. That road could be improved, and I am sure that it's immaterial to the deer hunters as to the specific road they use, so long as they finally arrive at the hunting ground."

"It cannot be done!" declared the Highway Official, with an air of finality.

A PECULIAR smile played over the Oriental's face. He slowly pulled a red leather wallet from his inside coat pocket. Opening it, he took out a pile of bills, one of which he handed to the politician.

"Have you ever seen one of these?" he asked.

The Pennsylvanian looked at it, picked it up, looked at it again, and handed it back.

"It's a grand!" he murmured at last.

"It is. At least, I presume you call a thousand dollars in your currency by that name. Now, watch me. I am placing these bills, one at a time, before your honored eyes. When you feel that your Department could close that road and permit us to enjoy the privacy we desire, please indicate your willingness to cooperate with us. I presume you are sure of privacy? It would be so annoying to have visitors—while I am placing the bills in front of you."

The Highway Official hastily left his desk. He did not return till his office door was locked and the window shades drawn. Then and only then did he seat himself and whisper, "You can start your argument." There was a slight trembling to his voice.

The Oriental took the sheaf of bills in his hand and, with a gesture that was almost grandiose, placed one of them in front of the politician. There was a slight pause, and then another bill was placed on top of the first, and then a third bill followed. Silently they fell like autumn leaves, only with a more definite regularity, as far as their landing was concerned.

The Official simply looked at the bills, trying to realize that each was worth a thousand dollars and that if he did not say "STOP" at the right time, he might fail to win one of them. Twenty-five—twenty-six—twenty-seven. What was the Chinaman up to? What did he want to close the road for? Why? Thirty-nine—fifty-three—Was it the same wallet? Or had he taken another one from another pocket? Was that last one sixty-nine or seventy-three. Hell! He had lost count. Something snapped, and he heard the Chinaman speaking to him.

"I am afraid that you are no longer interested. Perhaps I had better take my money and leave. There are other pieces of land that we can buy besides Resica. We do not have to have Resica for our purposes."

"Oh! I am interested, all right," insisted the politician. "Just a little hot in here and I lost count. How many are there in that pile?"

"I am laying them down, not counting them," whispered the yellow man gravely. "Still, if you wish to, I will lay down some more. No doubt the money will have to be divided, and you will have to keep a little for yourself."

"If you only knew, Mr. Foofoo, how hard a thing like this was to put over, you would turn your pockets inside out."

"My name is Wand Foo and not Foofoo," explained the Chinaman. "Now, suppose we ask your honored attention while I continue to place the pieces of paper you think so much of on the pile in front of you."

Once again the gesture of placing the bills, one at a time, began. At last the official held up his hand.

"That will do," he sighed.

"And you will close the road?"

"Yes. Of course, it will take a little time. I shall have to see some of the boys, and talk the matter over with them."

The visitor arose, and bowed courteously.

"I thank you for your attention. I neglected to say that when the road is closed and all the details attended to, I will see that you have a sum equal to the small pittance I have placed within your worthy hands. I might add that if you fail, or try in any way to evade the terms of our gentleman's contract, your lovely wife will become your lovely widow."

Without A Gate!

JAMES Johnson was a hardened politician, but his hands trembled as he gathered up the paper money and jammed it in a tight wad into his pocket.

"Not trying to scare me, are you?" he sneered, as he started toward the door.

"I never try to do anything," murmured Mr. Wand Foo, as he sauntered towards that door. "At least I never try to do anything without succeeding. I shall expect the road closed, Mr. Johnson; either closed or the cash returned, and I am sure you do not want to return it."

The official slammed the door on his visitor and locked it. Back at his desk, he started to count the money. One hundred and twenty thousand! And the Chink had said that there would be as much more when the road was closed. How much would he give the other boys? And what did the yellow fool want the road closed for, anyway? Two times a hundred and twenty thousand made a quarter of a million. That was a lot of cash to pay for an old road. Well, he had better get to work. That was a mean thing to say about what would happen if he failed. He ought to have slapped the Chink in the mouth.

But a quarter of a million was a lot of money, even if a part of it had to be split off to other interested parties; so James Johnson lost no time in starting the strictly legal proceedings necessary for the abandonment of the road leading through the Resica property. Of course, the affair caused some comment, ‘but relatively few persons were interested, and Johnson saw to it that the local newspapers made no great objections.

There followed a number of busy months at Resica. The road was not only closed; it was torn up. Several deep ravines were filled with the debris, which was in turn covered with several feet of rich earth and planted with laurel and rhododendron from the Stroudshurg Nursery. The road bed was also planted.

Soon there was but little proof that a hard-surfaced road had ever bisected the Resica tract. Then something more unusual happened. A contractor from New York appeared on the scene and started to run a fence around the four thousand acres. It was not an ordinary fence! The old people in Monroe County had been accustomed to fences of stone, of split rail, of barb wire, and even of roots of pine trees, but this fence was a novelty to them. It was of wrought iron, twelve feet high, the tops ending in lance points of needle-like sharpness. Woe betide the man or animal who, attempting to climb that fence, slipped on the top!

Another peculiar feature of the fence, which was not noticed till it was finished and then observed by only one person was the fact that the fence had no gate! There was no place of entrance or egress! Work had been finished, all the construction material taken away, even the nearest neighbors had ceased to be interested in the strange behavior of the rich fools in Resica, before a single person realized that the fence had no gate.

CHAPTER II

The Story of Resica

LUKE Hoofer, East Stroudsburg philanthropist, was drowsing idly on his front gallery one hot afternoon in August, 1936. He was not an old man, but his lire had been a busy one and he had reached the time when he appreciated long periods of relaxation. He had been born on Dutch Hill without a cent in his pockets, in fact without any pockets; and had attained wealth and some degree of local fame solely through his own efforts. He 'was somewhat surprised when he was aroused by the unexpected appearance of a nephew whom he had not seen for years. It was not to be wondered, that the first question he asked the young man was what he was doing in Monroe County.

"I am doing a little loafing, Uncle Luke," was Abe Summers' reply.

"Rather young for that, aren't you?" was the caustic answer. "When I was your age, I never loafed."

" Well, you know how to do it now. Seriously, I am up here on a little mission for the Government."

"That so? Seems I did hear the girls say that you had some kind of a Government job."

"That is about right. That is one—reason why I came to see you. What do you know about Resica Falls?"

"I know I could have bought it once for a few dollars an acre."

"I don't mean that. What kind of a place is it? Were you ever there?"

"I have been there several times," Hoofer replied. "First time when I was a little lad. I went up there and stayed all night. That was in 1880. When I was full grown I used to see it now and then when I was deer hunt. Lately one of my partners had a summer shack near the falls, and we used to go up there for Sunday dinner."

"Then you know about the place? Tell me about it?"

"In a way there is not much to tell. Way back in the last century some men from New York bought a large tract of land around a place called Moonshine Falls. There was a fifty-foot drop of Marshall's Creek at that place, and they figured that a lot of horsepower could be developed from the water falls. There was a fine grade of building stone there, and no grist mill for many a mile, so it seemed like a fine location.

"They were city people and must have put the cart before the horse, because they figured that if there was a mill, people would grow grain to take to the mill. I understand it was their plan to make flour and haul it to the Delaware and send it to Philadelphia by Durham boats.

"They dug the mill race and built the mill, and that was some mill, Abe. At least two hundred feet by sixty, with three-foot walls and as fine windows as I have ever seen. All the woodwork handmade and nailed together with hand-forged spikes. They built over twenty-five stone houses for the working men and a mansion: for the Boss, and when they finished they had a real town. Just then news came north that the States had won the battle of La Resica in Mexico. You see, we were fighting the Mexicans then, and that was big news, just like the battle of Gettysburg, Manila Bay and Belleau Woods were later on. So, they had a big time and free eats and the New Yorkers decided to name the new town Resica instead of Moonshine.

"I don't know what happened to the town. I suppose they ran the mill for some time, and perhaps they never had grain enough to make it pay. At least, the place was abandoned by the time the Civil War was over; and when I first saw it, it had already decayed. Everybody moved away. There seemed to be some kind of a curse on the place; no one wanted to live there, and yet I never could find out why. And when the land was offered for sale, four thousand acres of as nice woodland as you ever saw, but no one wanted to buy it. I understand that it has been bought lately by some foreigners."

"SO, it is Marshall's Creek that makes the falls?"

"Exactly. The same creek that makes Marshall's Falls lower down, before it empties into the Delaware. You see, Marshall was one of the men hired by the proprietors to make the celebrated Indian Walk, the time the Indians were robbed of the Shawnee Flats. Right up there was where the walk ended. The Indians were never satisfied over that business deal, and I guess they were robbed in good fashion."

"Let me tell you something, Uncle Luke," said the young man in a low voice. "I was sent up here to look into the Resica business, and there are some peculiar details about it. I have just been up there, on foot. In fact, I walked around the outside of the four thousand acres. They have a fence around the whole place."

"I have heard about the fence."

"It is there, all right, and it is a real fence, too. I walked around it. Tied my handkerchief on one of the iron rods and kept on walking till I came to the handkerchief again. It is one of the finest fences I ever saw and must have cost some money-but there is-not a sign of a gate."

"What's that?"

"There is no gate. I thought that there might be I removable section serving for I gate, but I do not think so. There is just a fence; no way to go in and no way to go out except by airplane, and the place is all woods; so, there would be no place to land."

"That is rather odd," commented the old man, "but let me tell you this, Abe Summers. That is not the only peculiar thing about that place. First is the price they paid—four hundred thousand dollars, and it is not worth it. Then there was the matter of the road. They had the road closed and the bridge torn down. I don't know what it cost them, but I believe some of the county bosses made a good thing out of it, and no doubt the highway people at Harrisburg were in on it. Anyway, the road was closed. Course you know about the fence, more than I do, because I have not been interested enough in it to drive up to see it. From what I hear, those people have put about a million dollars into that investment, and that is a lot of money to pay just for land."

"What do they want it for?"

"How should I know? Summer resort? Lumber? Electric power? No. Nothing like that. Did you examine the deed?"

"Yes; but that does not tell anything. Just gives the price and the description and the parties concerned."

"It tells one thing, Abe," remarked the old man slowly, "and it seems to me that that one thing is the most peculiar thing that has happened at Resica for a number of years, and enough strange things have happened there. That place was bought by a Chinaman, by the name of Wand Foo. Anytime a Chinaman buys four thousand acres of land in the deer country of Monroe County and puts an iron fence around it, why, that is a matter of real importance. I am not working for the government, but if I were, I would keep the Chinaman in mind."

"I will do that, Uncle. Guess I better be going. Say hello to the folks for me."

"Where are you going, Abe?"

"Back to Resica. I am going to find some way to go through that fence, or over it."

"You will find that Marshall's Creek goes under it," whispered East Stroudsburg philanthropist, as he shut his eyes and went back to sleep. The young Government employe heard and remembered the remark.

The next morning he slowly walked up the road from Marshall's Falls. It was early in the morning but already hot, one of those days without wind, when the grasshoppers whirr through the air and the upper sky of deep blue is dotted here and there with dragon flies, darting like miniature warring planes after impotent foes. It was just hot, without a breath of moving air. Summers took things easy and at noon came to the end of the road, an abrupt pause emphasized by the tall iron fence. There was no sign of a road on the other side of the fence, just a forest of fern, shrub and trees. Turning to the left Summers followed the fence.

Under the Creek!

IT was growing dark when the sound of running water warned him that he was near Marshall's Creek. It was running at the bottom of a heavily wooded ravine, and he was tired from his all-day walk. He made a hasty supper of chocolate bars and peanut butter sandwiches, washed it all down with water almost as cold as ice, made a bed from some ferns, and had no difficulty in going to sleep. He was only thirty years old, but he had slept on the sands of the Sahara, the muddy shores of the Amazon, and the snow-clad mountains of Alaska. The fern bed alongside of Marshall's Creek was real comfort, compared with some of his couches.

The next morning he was ready for some more Chocolate bars. The water was still cold, too cold to use for shaving with comfort, yet, true to his training, he simply had to shave before starting on the day's work. His belt was pulled up an extra hole, and he was ready.

"And I hope," he said to himself, "that I get something to eat before another day passes."

From close up the fence looked more formidable than ever. It ran down into the ravine, over the creek, and up the other side. It looked as though the iron bars went down into the bottom of the creek bed. Previous experimenting had shown Summers that the bars of the fence went several feet into the ground and were connected there by many strands of heavy barbed wire. It all seemed very difficult; in fact, impossible to get through. In order to obtain a better view of the top of the fence, he lay back on his bed of ferns. Just then he heard a squirrel scold and a blue-jay cry. Across the ravine he heard a twig snap. Raising his head cautiously, he saw a man at the top of the hill, on the other side, and that man was walking down into the ravine, along the inside of the fence. Summers hardly breathed. He was glad that the ferns and shrubs around him were so thick. Even after the man had gone for fifteen minutes, he still lay there. Then he cautiously sat up.

"That was a sentry," he exclaimed. "Those people are patrolling the fence. And unless I was dreaming it was an Indian, and what is an Indian doing inside the fence? An Indian working for a Chinaman! Some combination! But now is the time to cross the fence. Wonder how cold that water is?"

Rapidly undressing, he tied his clothes into a bundle and threw it over the fence. Then he dived into the creek. The plunge took him to the bottom of the creek bed. He was hunting for something that he was not sure existed, an opening under the fence, made by the swirling water in the spring freshets. The first time under brought no results except to show him that the bottoms of the bars were as sharply pointed as were the tops and that there was a lot of barbed wire in between. Again and again he went under, each time at different places until at last he found what he was looking for, a place where he could go under.

It was a chance and a rather desperate one, but one worth taking. He came out on the other side, fighting for air, and shivering from cold, his back badly cut by the barbed wire. The warm air felt good after the cold water. His clothes felt good. He was hungry and tired and sore, but the important thing was that he was inside the fence.

The next thing was to go to the falls. Resica Falls, where the mill race was, where the grist mill and the village of twenty-five houses had been built during the Mexican War. Resica, the mysterious! There he hoped to find a Chinaman and an Indian, and there he hoped to find an answer to the mystery of Resica.

HE followed the course of the creek, satisfied that it would lead him to Resica Falls. At or near the falls he was sure that he would find the new owners of the property. His course was slow, not only because of the necessity of caution, but also because he was held back by berry briars, large rock, and rhododendrons so thick that the place well deserved the name given it years before by the early settlers of Devil's Hell. It was hot in the woods, and he was tired and very hungry by the time he heard the sound of falling tormented water, which announced his proximity to the falls.

To his surprise, he saw a small bungalow ahead of him, and remembered his Uncle's saying that one of his partners used to have a summer camp at that part of the property, just on the other side of the iron bridge. The bridge was gone, but the little house remained, and was, no doubt, in use.

Abe Summers belonged to the now school of detectives, who believed that a straight line was the shortest distance between two points. At times their code is a dangerous one, often it results in the unpleasant death of the operator, but always there is a gamble in it that makes life worth living and more often than not it brings results.

The old style detector of crime would have secreted himself in the woods, spied on the house and the inhabitants for some days, formed conclusions as to their activity which way have been right, but just as possibly wrong, and would have avoided any contact with the parties being observed.

Summers was hungry and tired; he had accomplished one of the objectives of his program and had reached Resica Falls. Now he walked up to the door of the little house in the woods and knocked. No answer coming to his summons, he opened the door and walked in, through the little rooms—No one there; but there was a comfortable chair, and on the table in the back room a meal, apparently served for one per-son.

"And that person is Abe Summers," acknowledged the detective to himself. "I admit that it is not the act of a perfect gentleman to eat without being invited, but I am hungry. Besides, there are certain features about this house and this meal which makes me wonder if I was not expected. A man who spends a million to insure privacy has, no doubt, a very efficient secret service of his own. And there was the Indian. Not surprising to see an Indian, but it was a thrill to see him roam through the primitive woods, dressed m the costume of his ancestors."

He ate slowly and then cleaned up and washed the dishes when he was through. After that he walked leisurely through the house, examining everything thoroughly but disturbing and touching nothing. He spent over an hour studying a large map of New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania. It took him a long time to grasp the meaning of it, but at last he began to smile and relaxed in the comfortable Morris chair, which seemed to be provided for his special comfort.

"Very clever," he acknowledged to himself. "Remarkably clever. That explains the absence of a gate. Now that I am warm and fed and a part of my curiosity satisfied I think that I will take a little well earned sleep."

CHAPTER III

Wand Foo Explains

IT was late when he awoke. Candles in a silver candelabra were burning on the center table. On the other side of the table a man sat, his fingers interlaced, his gaze directed into vacancy. Summers took out his watch, looked at the time, wound it and replaced it in his pocket.

"I fear that I overslept myself," he stated simply.

"When I saw-that you were asleep, I did not wish to didurb your honorable person, Mr. Summers."

"You know me?"

"How could I forget an antagonist of years past! Surely you recall your activities in China, when you gathered details concerning our Russian friends? How can you forget Wand Foo?"

"I have not forgotten him," confessed Summers.

"I am so glad," purred the Chinaman. "Ever since you blocked my game in China, I have had you on my mind. When we came to America, I hoped that you would be selected by the Secret Service to investigate our activities. Not that it made any difference, you understand, but I felt that it would add to my pleasure to have you interested in our plans. Everything worked out nicely, and now you are our guest. I am sure you will be pleased to meet some of our compatriots, strange bedfellows in a way, but united by a common bond of hatred."

He clapped his hands and two men came from the doorways of the room where they had been concealed in the shadows. The Oriental introduced them.

"This swarthy gentleman is Georgius Sergiov. You can call him George for short. It will be so intimate and informal. He represents the great Russian republic, and comes to America, thoroughly committed to aid us in every way possible. When the time is ripe, his countrymen will come to the United States and reorganize the country according to their own ideas of equality and fraternity. At present this is a rich land, but when we finish it will simply be a province of a new nation yet to he organized; when the time comes, however, for this to happen, the directing force of that new world empire will be in Russia."

"And not in China?" interrogated Summers.

"Ah! The question of a cunning diplomat in trouble; and starting at once to raise discord among his enemies. Why should China crave power? We were cultured gentlemen when the Slav was a painted savage and the Anglo-Saxon a skin-clothed animal. We were writing and using gunpowder when the other world nations were in the stone age. Our history was lost in antiquity when Egypt was in her swaddling clothes. China can wait. China has always been able to wait. Four hundred million population and dying like flies, but hack of those yellow flies a national consciousness of world supremacy. We are willing to allow Russia to occupy America.

"This other gentleman has a rather difficult name to pronounce, but in English it means Troubled Water. He is a full-blooded Indian and as such is more entitled to the name American than you or any of your people. His being here has a singular history. He is a lineal descendant of the Indian tribes who once owned all this land. They were cheated out of it, badly deceived at the time of the Indian Walk. His family lived here at Resica. Naturally, they never forgot the treatment accorded them by the white race. For four generations they have been made to live on the western reservations, but always they remembered their home. When the time came, they returned to it—not all of them, of course, yet all who were left of the family.

"But Troubled Waters retained the traditions of his family and their knowledge of Resica and the falls. After he became rich from the sale of his Oklahoma oil lands, he traveled and I met him in China, and after we talked matters over we became friends. He told me about the falls and the tunnel, and I saw possibilities enough in the idea to propose a certain plan to the Russian government. So we three are here, just the three of us, and now you have joined us."

"AND that makes four," commented Summers.

"And I am sure that you will be interested in our plans, Mr. Summers, because you have always had such a flair for being interested in other people's business. Briefly speaking, we are going to conquer the United States. Just the three of us. Is not that interesting? Of course, our armies, later on will come into the country and mop up the place, but the main work will be done by the three of us."

"But I thought there were four of us?" asked Summers.

"You are going to be just an interested spectator. Remember that we did not invite you. Since you are here, however, we intend to have you stay. Here is our plan. Centuries ago a race, who lived here before the Indians, built a tunnel from Resica Falls to the ocean. At the far end we have a very pretty summer home built, and no one, not even the clever Mr. Summers, would suspect that one could walk from the cellar of that home to Resica Falls. Our precious supplies are being carried from there. Someday Government officials may come to our iron fence and demand admission and we will very gladly let them in and show them everything, but at the end they will have learned nothing.

"Our machinery is very simple. At the top of the falls, at one side, in a cave, we place the barrels. One at a time these are connected with a little silver pipe which empties the contents of the barrel, a drop at a time, into the water just as it dashes over the falls to mingle with the Troubled Waters. That is the part of our Indian friend so very much enjoys. He sits there and watches the drops disappearing so evenly over the falling water. His race died that way, one at a time, like dropping water, or falling leaves in autumn. Now, as he watches the medicine falling into the water, he sees the doom of the descendants of the people who destroyed his ancestors and robbed them of their homes.

"That is our modern method of making war. Did you know your nation was at war? No doubt you are ignorant, but war has begun. We have started now—the drops are falling, sixty a minute, and thirty-six hundred in the hour. Soon we will have results in Philadelphia, and the smaller cities around Philadelphia. Then we will do the same thing to New York, and New Orleans, and Los Angeles. And when the morale of the people is destroyed, when fear covers the land like a panic, then our troops will move in, how—you need not know. But it means the end of the war."

"That is very interesting, but I am not sure of your conclusions," said Summers. "I cannot see how three of you can accomplish all that disturbance."

"You weary me with your arguments and objections," answered the Oriental with an air of finality. "Friends, suppose you show him the pipe and the barrels and then place him in the tunnel and lock the iron gate. I might say, Mr. Summers, that the tunnel is many miles long and you can wander through it as you wish. At the other end you will also find a gate; so, you can stay there and think, and while you are doing it, your nation will begin to die."

The detective saw that resistance was useless. These three men were not in any way ordinary beings. Life to them was a commonplace, murder a banality. For some reason they did not kill him at once, but he knew that they would change their mind in a split second if he showed resistance. He allowed them to search him, and followed them into the twilight.

The last rays of a setting sun were turning the boiling water of the falls into a fairy land of fantasy. The three of them, the Russian, the Indian and the young American, walked through the wood till they came to a little shining pipe which seemed to come out of the rock on one side of the falls. The free end hung over the falling water.

"The barrels are in a cave over there," growled Sergiov. "The Chinaman said we were to show you the barrels, but what's the use! I think he must be foolish to even let you live."

"If I had my way," commented the Indian, "I would take him out on that rock and slit his throat and let his blood join the medicine. Still, orders are orders, and I suppose we might as well carry them out. But what the idea is, is too much for me. Come along with you. Have you the key, Sergiov?"

"I have the key, and here we are," announced the Russian. "Orders were to turn him loose in the tunnel, but nothing said as to how." With that he struck the detective a crushing blow on the head with a blackjack.

It was hours before Summers really knew what had happened to him.

The Great Epidemic

THE events of the next two weeks will always remain as one of the great tragedies in American history. There had been previous disasters by war, fire, flood and tornado. Cities like San Francisco had been leveled by earthquakes. Other cities like Chicago razed to the ground by fire. But never before had two million people gradually gone to sleep and kept on sleeping.

The first cases were so scattered, and so unconnected that the real peril of the situation was not realized. Here a few and there a few of the people of the lower Delaware Valley went to sleep and could not be aroused. The next day there were hundreds more of the sleepers, but even then the symptoms were so mild, the sleep was so natural, that there was no realization on the part of the authorities as to the meaning of it all. In fact, it was not until the epidemic had taken thousands into the arms of Morpheus that real apprehension began.

It was thought at first that it was a widespread epidemic of lethargic encephalitis.1 But certain symptoms of that disease were uniformly absent. In fact there was no symptom except a natural sleep, perhaps heavier than usual. The women and children seemed to be the first affected, and they, simply feeling drowsy, went to their beds. The men, because of a greater resistance, were the last to be overcome. Inside of a week, over two million persons were asleep.

1: A variety of brain fever known as "sleeping sickness."

It meant an end of all activities in the great city. Transportation stopped, the production of power ceased. Commerce, the ordinary relation between people, came to an end. The waitress in the restaurant, the mechanic at his bench, the broker at his desk, the surgeon operating on his patient—one and all became sleepy and yielded to their desire to rest.

It did not take long for the great medical minds of the nation to realize that something terrible, menacing, deadly, was at work in Philadelphia. Two things had to be done. One was to take proper care of the victims, the other was to determine just what was causing the sleeping epidemic.

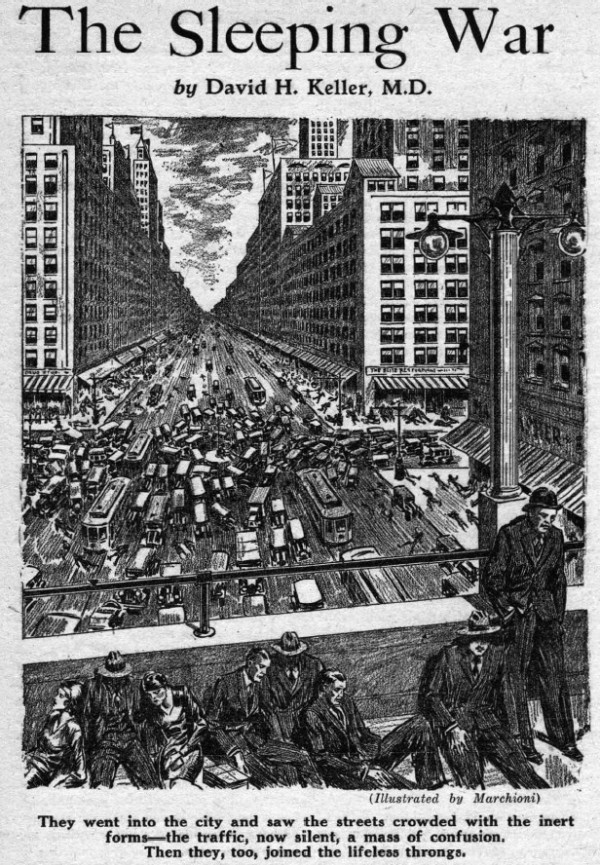

It is to the credit of the medical fraternity that at this time there was no end of volunteers who went into the doomed city to care for those who lay in a deathlike trance. The greatest medical minds of the nation volunteered to determine, in spite of the obvious danger, the cause of the epidemic. They went into the city, saw the streets crowded with the inert forms—the traffic, now silent, a mass of confusion. Then they too joined the lifeless throngs. Few returned to tell the story.

The thought of a great city, devoid of all protection, helpless to the last degree, stirred the imagination of the underworld. At once a small army of degenerates, reckless to the last degree, gamblers all, moved like a devastating army towards the city of the sleeping people. They went to rob and they remained to sleep. On the streets, with their bundles of loot beside them they fell down to their tortured dreams, victims of the same dire fate that stilled the activities of their intended victims.

It was felt that in spite of the best intentions little could he done for those already suffering from the weird disease. The Government threw a line of soldiers around the city and finally forbade either entrance or egress. Ships evaded Delaware Bay. A silence, greater than even the silence of the dead, hung over the dreaming metropolis.

A nation trembling from sympathy exerted all its mental resources to solve the problem that had destroyed the consciousness of one of its great cities. The world, apparently a unit in sympathy, offered any resource at its command. Philadelphia, long jeered at as the sleepy city, was remembered at a thousand altars in prayers as earnest as they were impotent.

And then a message came from the Soviets, the Red Nation of the World. It suggested that other American cities in addition to Philadelphia might fall asleep; and offered as an alternative submission to a peaceful conquest by Russia and China.

THE message was delivered secretly to the President of the United States. Whatever his motives, his decision was to keep it secret. There is no doubt that had he done otherwise, a national panic might have resulted. Millions of men were still out of work, the classes were disturbed over the Philadelphia situation, the masses were ripe for revolt. Rightly or wrongly, the President decided to allow a few days to lapse before arriving at a decision.

Meanwhile, the Coast Guard of New Jersey had taken an unconscious part in the course of world politics. They had had under observation for some months a very ornate, but isolated summer home. It was, according to their conclusions, the headquarters of an aristocratic set of bootleggers. Now and then a ship steamed in and unloaded a number of small barrels which were carried via boat and wheelbarrow to the summer bungalow. In spite of their closest watch, they had failed to see any of it leave the house for distribution.

A wild night had been selected for the unloading of the next lot of kegs. The Revenue Officers were on hand and the attack on the house was a perfect success. The Russian crew were captured, and in the cellar of the house two Chinamen escaped a similar fate by committing suicide. The Guards were just leaving the cellar when they heard a call for help. Following the sound, they came to an iron gate hid behind some empty kegs. A hoarse, feverish voice cried to them desperately and explained to them that the keys to the gate might be obtained from one of the dead Chinamen.

A few minutes later Abe Summers staggered out into the cellar and collapsed on the floor. The first thing that he did on recovering his consciousness was to go to the telephone and tell Mr. Wand Foo, in very excellent Chinese, that the ship had just come in and had succeeded in landing thirty-seven kegs of the drug.

Summers had not been very happy. The days spent in the tunnel, with an iron gate at each end, had been tortured years. He had found water in abundance and a few living things, like salamanders, and toads. He had groped his way through the dark all the distance from Resica to the shore of the Atlantic Ocean, only to find another gate. His life had been an adventuresome one, but never before had he come so close to the consciousness of death. And his sufferings were made all the more horrible by his realization of an unknown danger which, in some way, was threatening the people of the Delaware Valley and which danger he was unable to prevent.

Now, for a wonder, Fate had not only saved his life but had placed him in control of one end of the tunnel. First, he made the effort to keep the three conspirators in ignorance of the fact that the outlet to their fortress in Resica was in the hands of their enemies. The next thing was to find what had happened to the people of Philadelphia during the long, tedious, tormenting days he had wandered, a hungry desperate man, in his tunnel prison.

It did not take long for the Coast Guards to answer his eager questions. The people of Philadelphia and the vicinity had fallen asleep, victims of a peculiar and terrible epidemic that, up to the present time, had not even been given a name. That was it! That was the explanation of the liquid dropping through the silver pipe into Resica Falls! Even though greatly diluted, it had drugged the city. It must have taken so little to produce such mighty results; and there were many barrels left. Thirty-seven had been landed that night. Enough, if properly distributed, to numb the sensibilities of the nation, certainly enough to so stagnate the life of the great cities so that the conquest of the United States by the Soviets would be simply a matter of time.

Summers sat in a chair in the summer bungalow and thought it all out. The Russian and the Indian were just pawns in the game. Wand Foo was the real brains. It was the Chinaman who had formulated the attack. It was his shrewd brain that had determined just what drug to be used. It was, no doubt, something that was unknown to the Occidental pharmacist. The yellow man had boasted of the superior knowledge of his countrymen.

Summers was a detective, not a physician, but it did not take a medical mind to leap across the picture puzzle and arrive at the next step in the solution. If Wand Foo knew the poison, he also knew the antidote. There was only one thing to do. Get the man and make him tell!

CHAPTER IV

Tracks of Mud!

THE detective slowly ate crackers and water, sweetened with sugar. He was weak, but, gradually, as the sugar began to circulate through him, he began to think more clearly. The only way the Chinaman could be taken alive was by surprise. Even if Resica was captured, there still remained the long, dark primitive tunnel, a bad place to capture a man in, especially if the man was desperate.

Summers felt peculiarly alone. He had been sent out by the Secret Service with the instructions to clear up the Resica mystery. The final statement made to him was that in no emergency was he to do anything that would cause publicity. It was to be a one-man game. And more than ever did the detective see the wisdom of this advice. If the peoples of the United States learned the real facts, war could not be prevented and war with Russia, China and Mexico would mean war also with Japan. It might be a successful war and, no doubt, it might be a popular one; but it would mean the loss of millions of lives. It would rock the peace of the world.

Meantime, the Coast Guards were growing more curious. They felt the air of mystery, and were anxiously awaiting the time when they could ask a thousand questions. It had been useless to question the Russian prisoners, but who the starved white man was who had shown them his Secret Service badge, and what interest he had in the bootleg game they did not know. Whom had he telephoned to? Summers could not satisfy their curiosity.

"You'll have to consult my Chief," he explained. "But I will say that these men caught me and nearly starved me. Lucky for me you raided the place when you did. Better be careful of that liquor: Not ordinary stuff, by any means. Give me a gun and let me watch these foreigners while you go and report the affair to your Headquarters."

He spoke with an air of authority, and they believed what he said. "Then they came back, they found two dead Russians. There was a note pinned to one of them with the simple explanation that they had tried to escape. The detective was gone. It was not till some minutes later that some one suggested that they look in the cellar. When they did so, they found that the iron gate was locked. Outside the house they found the muddy tracks of a motorcycle—leading to the cellar door.

They were members of the Coast Guard, but they were also very human men. The statement made to them that the liquor in the barrels was no ordinary stuff interested them. They tried some. When the relief Guards came, they found two dead Chinamen in the cellar, two dead Russians in the parlor and three sleeping Americans in the kitchen. There was no one left to tell the story of the starved man in the tunnel.

* * *

Wand Foo was rather happy. He had every reason to believe that the morale of the nation was badly undermined by the calamity in Philadelphia. Thirty-seven more barrels of the drug had been successfully landed in the summer home which secreted the other end of the tunnel. Summers, who had done him great harm in past years, was slowly starving to death in the tunnel. Perhaps it would have been best to take the Russian's advice and killed him at once, but it certainly was pleasant to think of his slowly dying, with ever-increasing hunger gnawing at him like a fox. Everything was working out nicely, but there was one thing that worried him and, try as he would, he was unable to determine what it was.

He wondered if he was growing old, losing his cunning? In the meantime, he formulated plans for the attack on New York City, an assault that would end in the sleeping death of eight million persons. Perhaps after that the President of the United States would realize that it was best to answer letters from foreign nations.

SUMMERS had had one experience with the prehistoric tunnel. Bleeding from the scalp wound from the terrific blow of the Russian, he had recovered consciousness in that tunnel and had staggered under the Delaware River and under the width of New Jersey only to find at the end of a wild delirious, staggering walk there was an iron gate at the other end. During those days of starvation, hope had remained in his heart for no other reason than the fact that he was an Anglo-Saxon, fighting for the very life of his country.

For the second time he entered the tunnel, but this time he went in voluntarily, wheeling a somewhat muddy but serviceable motorcycle with an excellent head lamp to light his way on the wild ride back to Resica. He had locked the gate behind him, because he did not want any interference with his plans. He had also two automatics and plenty of ammunition, several packages of crackers, a can of sardines, and unlimited hope. He was not sure that the key to one gate would unlock the other one, but he hoped so.

Back of his anxiety to return to the Falls was a curious interest in the tunnel. He had been told that it was very old. Now, with the light guiding his way, his hands gripped about the handlebars and the roar of the machine filling the cave, he was able to confirm this statement. The floor was worn smooth by the millions of feet that long centuries ago had walked from the Ocean to the Falls. On the walls were rude carvings of animals who ruled America when the Gulf of Mexico began at St. Louis and who now remained only as rock pictures and fossil bones. Summers determined that he must not be the last one to travel through that tunnel. When this "little affair" was cleaned up, he must make the existence of the tunnel known to the Smithsonian institution.

He chugged on and on with the regularity of a machine. There were short periods of rest to be rid of the deafening roar of the machine; and scant periods for eating. At last, with a sigh he saw cracks of daylight at the other end of the tunnel and heard the thunder of the falls beyond the gate. Daylight indeed, but little more, for once again in his mind he saw Resica at the close of the day, at the crimson purpling of a sunset.

Now for the key! Would it open the gate? It did. Summers took that as an omen. From now on it was to be a poker game, but the cards were stacked. One man against the representatives of three great nations, two living and one dead; and the one man held all the aces.

He locked the gate behind him. His first thought was to stop the constant dropping of the drug into the water. After that was done he would attend to the Russian and the Indian. He was no longer a calm, methodical detective. He had become, from necessity, a killer.

Lady Luck was with him. Troubled Waters was lonesome and a trifle bored. There had been long periods of complete inactivity and a gradual deepening of the feeling that the Chinaman did not consider him a vital factor in the program prepared for the conquest of America. He was not even confident that if those plans were carried out successfully, the-remnant of his nation would be happier or more prosperous. He had seen something of the Russian temperament in the last few months, and he was not sure that the Russian would he as kind a ruler as the Saxon had been.

He had hoped some day to he able to live at Resica, but who was there to live with? His race was almost gone. There was not a pure blooded Indian maiden in his tribe, and the half breeds would rather live in New York than amid the solitude of Resica. He sat cross-legged on the rocks at one side of the Falls and thought over these matters. The thunder of the water lulled his caution, while the shimmering sheen of the sun in his eyes hypnotised him into a twilight sleep. He awoke for a second with the crash of a bullet in his brain, died as he plunged downward over the falls and went to sleep eternally in the dark green of the whirlpool below.

"And now for the Russian," whispered Summers, as he started to walk to the little bungalow. Luck was again with him. The two men he was blunting for were in the living room, laying their plans to leave Resica the next morning. They were seated on opposite sides of a table, and the Russian was facing the window.

A Lesson in Torture

"I HAVE it now!" cried the Chinaman, with a complete departure from his usual suave manner. "Something has been troubling me, and now I know what it is. We will not wait till tomorrow to go to the cottage by the ocean. We will go tonight. Listen to me and learn how the little things of life are of the greatest importance. My servant telephoned. to me that thirty-seven kegs of the poison had been successfully landed and were stored in the cellar. But that servant is a well-educated man. He has the blood of Mandarins in him and was educated in England. He spoke to me in Chinese, but one phrase he used was not inflected in exactly the manner of a Mandarin. I heard that phrase, but my mind slept. Now it is awake. Georgiov, that was not, my servant who spoke to me over the telephone."

"Then who was it?" asked the Russian, somewhat annoyed at the sudden garrulous behavior of the Oriental.

"That was none other than my friend, Abe Summers."

Just then a shot filled the silence of the room. The Russian slumped in his chair and dropped to the floor. Once again the killer, fighting for the security of his country and not willing to take a single chance, had spoken.

"And do not make a single false move, Wand Foo," commanded Summers, "and you better keep your hands up till I frisk you. I do not want to kill you, but I may have to, if you don't behave."

Had the Chinaman been dealing with a stranger, he would have taken a chance, but he had come in contact with Summers once before. He felt that for the present he was in a precarious position. At any moment he expected the Indian to come, and then, even with the Russian dead, there would be two to one. Summers might be persuaded to talk; the white man might be bluffed, outwitted. Wand Foo hoped for the best, but at the same time, obeyed the command and raised his hands.

The detective tied those hands with the Oriental's own sash. He tied his feet and body, to the chair with a rope he had carried with him from the seaside bungalow. When he finished, the Chinaman was trussed in no uncertain manner. The dead Russian was dragged into the next room, the center table pulled to one side, and then Summers started to talk.

"No use to spill a lot of words, Wand Foo. I know what you tried to do to my country. In spite of your efforts I lived on, though I nearly starved in the tunnel. Now I am back, and I hold all the aces in this poker game. Poor Troubled Waters is dead at the bottom of Resica Falls. Your Russian friend is dead. So are your people on the Atlantic Coast. Just you and I left, and you are rather helpless.

"Now, I know that you are no fool. You know a lot more than I do—about some-things. You know all about this sleeping drug you have put into Resica Falls and from there into. the Delaware River. But you know another thing about that dope; you know the antidote. And you are going to tell me.

"Of course you will refuse. You, think that I will kill you and then you can save your face, and join your honorable ancestors. I would not think of killing you, not all at one time. But when you had me in your power in China some years ago, you gave me some personal lessons in torture. Do you remember? Well, I am going to pay you back—teach you the same lessons, and maybe show you some new tricks; but just as soon as you tell me how to save those unfortunate sleepers in Philadelphia, I will stop the education. Now do you understand?"

"You cannot torture me, Mr. Summers," announced the yellow man with a smile. "You are a white man, and white men do not use those methods. You would kill me, but you would not torture me."

"Is that so? Well, all I can say is that you better watch me for the next hour. You are going to tell me what I want to know, and I know that you are going to. In the meantime, I will build a fire in that fireplace and start to work."

HALF an hour later Wand Foo agreed to come across with the information. He was not at all happy, for various reasons, but the part that hurt the worst was the consciousness that he had made a mistake in estimating the character of an Anglo-Saxon who was aroused.

Both men were sweating. No one will ever know what Abe did to Wand Foo, but it was sufficient to break the determination of the Oriental to die rather than surrender the information.

"Enough!" he cried. "Stop! The remedy is simple. A few drops of a ten percent solution of sodium bicarbonate injected by hypodermic under the skin will wake the sleeper."

"Wait a minute till I write that down. That is the truth, is it?"

"Absolutely."

‘ "Have you any in this house?" "Yes, in that table drawer. I always have some hypodermim loaded—in case of accident."

Summers confirmed the statement, placed a hypodermic syringe on the table, and left the house. Twenty minutes later he returned, and explained his absence.

"I went to get some of that poison. You lied to me in the past and you might do it again. I am going to make you drink some of this stuff, and then, after you fall asleep, I am going to give you the antidote. If it works, you will awaken. Now, open your mouth. Oh! Yes, you will. Want some more persuasion? Here, drink this. I am going to give you a big dose, and then I am going to find something to eat and take a little sleep myself."

He enjoyed that meal, but before it was over he heard the Oriental call him.

"Ah! Mr. Summers, a little matter I forgot—in the excitement of the last hour. There is a little vial of tablets in the drawer. I am not sure of their Latin name, but I am sure that your chemists will be able to identify it. One of them has to be dissolved in the sodium bicarbonate before it is effective. I thought that you should know that."

"I thought there was something like that," answered the detective with a grin. "Now you just go to sleep, and when you start to snore I will shoot you with the needle and wake you from bye-bye-baby land. I hope you have a happy dream."

Summers did not mean to sleep so long, but he was completely tired, and it was daylight before he awoke. There was no doubt about the sleep of the Chinaman; it was a narcosis from which no amount of yelling, shaking or pinching could arouse him. The detective fixed the antidote, injected it and then started to eat breakfast. In an hour the Chinaman was awake.

"It worked," agreed Summers. "Now you and I are going to Washington, just as fast as we can, to tell our story there."

"I cannot walk through the tunnel," said Wand Foo, decisively. "Not with my feet the way you left them."

"We are not going through the tunnel. We are going through the fence. You will walk with your hands bound and I will ride behind you with a very muddy motorcycle until we get an automobile."

"There is no gate to that fence."

"Think that I do not know that? But you know how to get out. Secret panel or something, and you are going to show it to me; either that, or I am going to hoist you up on top and stick one of those iron points through you. You are positively the hardest man to handle I ever argued with. You do not seem to understand that I mean business."

Six hours later Luke Hoofer received a call from his nephew. The young man did not even have time to leave the automobile, but called the old man out to the street.

"Just how bad are things in Philadelphia, Uncle?"

"Bad enough, Abe. Millions of people asleep, and the whole district quarantined. Where have you been?"

"To hell and back again. By the way! Uncle, let me introduce Mr. Wand Foo, the owner of the Resica Falls property. The place is for sale, and the price is low, and I have half a notion you could buy it."

The East Stroudsburg philanthropist looked at the Oriental in a very interested manner.

"You have him all tied up, Abe?"

"Sure. He has a habit of arguing, and I want to be sure that I always come out on top—of the argument."

* * *

The President of the United States was closeted with two of the greatest physicians in America. They had come at his request to tell him the latest developments in the Philadelphia epidemic. To their chagrin, they were forced to admit that so far both the cause and the cure of the disease were unknown to them. The sleepers were still asleep and the weaker of them had wasted away; even the stoutest of them would soon die of malnutrition.

In came the private secretary. There were whispered conferences. At last the President yielded, and the secretary left the room, to return instantly followed by the Chief of the Secret Service, a weary looking detective and, between them, a Chinaman in soiled clothes securely tied in every possible direction.

"Mr. President," began the Chief. "This is Mr. Abe Summers, one of our men, and he has a story to tell you about this Chinaman. I though you would be interested."

Summers told the tale from start to finish. Parts he glossed over and he never did explain why the Chinaman could not walk. He ended by placing a bottle of the sleep producing drug on the table, and alongside he placed the bottle of little tablets and several ten cubic centimeter syringes filled with the sodium bicarbonate solution.

When he finished, a physician sighed:

"I wish we had thought of that. It sounds plausible. The story explains why certain portions of the Philadelphia community were not affected like other parts. Some of the reservoirs are filled from the Schuylkill instead of from the Delaware. With the drugs in our hands, we should have no trouble in identifying them, and then it is only a question of time before we can inject the sleepers. Those who are not too far gone can still be saved. The country owes you a vote of thanks, Mr. Summers."

"You can pay me best by keeping out of it. I just did what I was ordered by the Chief to do. But there are two things I want to do. I like the Resica Falls property, and if I can be made owner of it in some way, it will please me immensely; and then I have been carting Mr. Wand Foo around a long time, and I wish some one would take him off my hands. Ha needs hospital care and after that he should be kept safe. He is really not a pleasant man to have loose."

THE END