Help via Ko-Fi

ALMOST IMMORTAL

By AUSTIN HALL

Author of "The Man Who Saved the Earth." etc.; Co-author of "The Blind Spot"

The snatcher of souls had chosen his victim. How could he be outwitted?

CHAPTER I

ROBINSON's DECISION

THERE were three of us: Robinson, Hendricks, and myself.

Robinson had had a varied career, soldier, policeman, lawyer, and several other professions which he never divulged, but which kept continually cropping out in his conversation.

I have an idea he had been a sailor and had sailed over all the seven seas. There was no country which he had not visited, no people nor race nor tribe of which he knew not the characteristics, nor any institution with whose history and development he had not an intimate knowledge.

Indeed, it was on the historical side that he was the most remarkable. I have never seen such a man. The scope of his intellect seemed to embrace everything. From the Chaldeans down, all was to him an open book. He appeared to know as much about Nebuchadnezzar as about me.

All the great lights of history were to him as men living and present; he would tell of their foibles and greatness, their manners and personal appearance with as much vividness and distinctness as if they and not I were seated by his side for portrayal. Then he would lapse off into gibbering of a kind which I could not and would not understand, into tongues obsolete and forgotten, which he chose to call Chaldaic, Sanscrit, and what not.

Again he would drift off into anecdote and speak of an incident wherein Caesar and Pompey, and another character I knew not of, were the principals. He knew anecdotes by the million; there seemed to be no limit to the supply with which he amused me from day to day; nor do I ever remember his relating the same one twice.

Big and little, large and small, people and kings, he appeared to have them all at his fingers' ends. I wondered sometimes that he did not write history, he who knew more than all the historians put together. Once I asked him, but he only shrugged his shoulders.

"I have no time," he laughed. "I am a loafer. Besides, I know too much. Were I to tell the truth I would be called a liar."

The other man, Hendricks, was a friend of Robinson's, an attorney who had come up to the mountains to recuperate. It seems that he and Robinson had just been through some terrible ordeal, which had played havoc with them, both mentally and physically.

He had not the wonderfully retentive memory of his friend, nor his marvelous command of language, though he did appear to have a fair smattering of the law, and a very fair education. Most of the time he spent as I did, in loitering about and in listening to the everlasting eloquence of Robinson.

As for myself, I was purely passive.

It was our custom to come out on the veranda at night and to discuss books under the fragrance of a good cigar.

I had on this day been reading a novel of the very cheap and sensational order, one that had to do with a plot of the purely imaginative type, wherein the characters were taken out of the life of ordinary reality and transplanted into the realm of the grotesque and the terrible.

I held that all works of true literary merit should contain, as a basic feature, the elements of real life, and that in' their ramifications they should hold by all means to life as it is, and to avoid transgressing the regions of the impossible. For the work at hand I had but little use, and I criticized it severely as a thing absurd and ridiculous.

It was moonlight, and for some moments after I had finished my tirade, we sat watching the shadows among the hills. Robinson was usually loquacious, but tonight he was strangely quiet. Undoubtedly he was thinking. He scarcely noticed my talk at all; but sat there working his cigar at both ends, chewing and smoking, dreaming, and apparently in the land of far away, until the moon, passing behind a cloud, and the flood of mellow light ceasing, he turned to his friend.

"Hendricks," he said, "how long has it been since I escaped from that beast?"

"Third of January, and this is the third of May," answered Hendricks. "Exactly four months. Why?"

"Oh, nothing much. Only our friend here is skeptical, and believes only in the commonplace; he is like all the rest of mankind, only I think we can cure him. I propose that we relate to him our own experience, and prove to him how one man managed to live for ten thousand years in the enjoyment of youth and vigor, and how I came to be devoured alive, and how it happens that I am living tonight to tell the tale."

"Tell him, if you wish," answered Hendricks. "I'll corroborate you as long as you stick by the truth."

Robinson moved his chair closer to mine and sat so that I could get a full and a perfect view of his whole person.

"Do you see any marks on me?" he began; "any tooth marks or anything like that? No? Yet would you believe me were I to tell you that I have been devoured alive. Not only that, but digested and enjoyed."

"I certainly would not," I answered.

"Of course not," he replied, "and really I don't much blame you. Time was, and not so many years ago at that, when I would have said the same thing. Nevertheless, what I am about to tell you is the gospel truth, as you will learn from my friend Hendricks."

And Robinson plunged instantly into the following story.

ABOUT six years ago, after some time spent in the islands, I returned in a practically penniless state to San Francisco. Besides my baggage and wearing apparel I could not have possessed much more than forty dollars.

One day, after I had tramped over a great portion of the city, climbing skyscrapers, invading factories, and I know not what in my never-ceasing search for employment, I struck a crowd surging up Montgomery, and like a chip in the tide, drifted along with it.

In my despair and half-heartedness I little dreamed of the strange and marvelous existence of which I was soon to become a part. Of an existence which was to reward me with a learning which I think has never before been attained by mortal man, and a wealth of such proportions that the human mind can scarce conceive of its vastness.

Both sides of the street on which I walked were lined by office buildings on whose serried windows were hung, painted and gilded, the signs and placards of numerous lawyers, doctors, corporations, and insurance companies. Among them my attention was attracted to a particular attorney's sign, whose reading in gold letters had on me a strange and gladdening effect. It read:

W. E. HENDRICKS

Attorney at Law

I had known a W. E. Hendricks before going to the islands. We had been classmates and roommates while at college, and I remembered now, with a flash of eager hope, that it had always been his desire to build up a practice in some Western State, preferably in California. I can hardly tell you how happy and excited that hope made me.

A MOMENT later I was in the office, all trembling with eagerness over the voice which came from the adjoining room. Sure enough it was Hendricks—Bill Hendricks, the one man whom above all others, under my present indigent circumstances, I would have chosen to meet.

Naturally I moved my belongings to the quarters of Hendricks, where, under the spur of poverty, I lived on his bounty while seeking employment.

One morning, about a month later, I entered the office and found Hendricks, as usual, deep in the intricacies of his profession. Scattered over and about his desk were his everlasting law books, legal papers, and documents, an evening paper, and to one side an early edition of the San Francisco Mercury, which, without looking up, he passed over to me for perusal.

"You will find," he said, "an advertisement in the help-wanted column which it may be to your advantage to look up."

The advertisement was marked with a blue pencil, and I had but little trouble in locating it. It was for a companion, and I must say it was the most peculiar advertisement of its kind that I had ever read. It was worded something like this:

WANTED—A companion for an elderly gentleman; applicant must be about twenty-six years of age. exactly five feet eleven inches in height and must weigh between one hundred and eighty and eighty-five pounds. He must possess a small knowledge of the law; also he must be a good conversationalist and be able to give proofs as to his perfect health and vigor. No applicant with any symptom of disease or any infirmity whatsoever will be considered. Anyone answering these qualifications can procure immediate and lucrative employment by calling, et cetera.

The address of a Dr. Runson on Rubic Avenue followed.

Strange to say, although the conditions were so peculiar and various, and so impossible of filling for the ordinary man, they fitted me to a nicety.

It was almost as if I had received a special order to report for duty. I was exactly five feet eleven inches in height, and had weighed only the day before, one hundred and eighty-three pounds, so that I had a leeway of two pounds in one direction and three in the other. Besides, I possessed a college education and knew considerable about the law. If I had any weakness or infirmity of any kind I had not as yet noticed it. On top of this, I was a very fair conversationalist; at least had always been considered so by my friends.

The position seemed made for me, and I decided to apply for it immediately.

CHAPTER II

DR. RUNSON

AN hour later I had made my way to Rubic Avenue, where I found the rendezvous to be a most comfortable old two-story house with large, deep, easy-looking verandas, a splendid lawn, and green-shuttered windows.

In response to my knock a neat little woman of some fifty summers—or rather winters, for the quiet, troubled look of her face, and the gray of her hair reminded one more of that season than any other —appeared at the door.

She was trim and neat, and apparently expecting me, for she quietly opened the door and bade me, in a kind, motherly voice which I noticed at once, to enter, and without another word pressed a button beside her and disappeared, leaving me in the hall alone and waiting. In another moment a door opened above and a voice came down the stairs—a musical voice, but masculine and full of vigor.

"Is that you, Mr. Robinson? Just step up this way, please."

Naturally I had expected to meet a stranger, and was not a little surprised at hearing the sound of my own name spoken from above.

"It is," I answered. And I remember wondering how in the world he could know it, and who in the world he could be.

"I am glad to see you, Mr. Robinson," he greeted me when I reached the landing. "Exceedingly glad. I was expecting you. Step right in."

He opened the door and led me into a study, or rather a sitting-room, or still better, a combination of the two.

"Sit down and we will talk business," he said.

A total stranger I was sure. I had never seen him before. Of my own height; but sixty; hair turned gray; of my own features, and might have been my twin brother but for thirty years or so; hands white and immaculate, slender and deft like a gambler's; neat, dressed in black, clean shaved, and a gentleman.

All this I took in at a glance as you would take in a photograph. Nothing uncommon, nothing extraordinary, everything, barring the resemblance to myself which I might have had perfect reason to expect. Then our eyes met.

Someone has said that the eyes are the gateway to the soul. This was an archway. The idea of the common vanished and in its place was the extraordinary, the magnificent. I will condense it all by my own flash of feeling—the eyes of a multitude.

You could not look into his eyes without the feeling, instinctive, but always present, that you were not looking into those of one man, but the eyes of a thousand. However, it was not an unpleasant feeling, more of strength, of power; the impression of an indomitable will which not all the world could change. Nevertheless they were pleasant, with a kindness and a jovialty which danced and fascinated you.

"Now, Mr. Robinson," he began, when we were seated, "let us proceed. I shall talk first, for it is my nature. I am always first. You will be surprised at what I tell you; but do not wonder at that, as I am, I will admit, an extraordinary character. Though you will most likely find me common enough for a few months.

"Now, I decided yesterday to advertise for a companion, and in looking over the available candidates I found you the most desirable. I knew you could easily be reached through the papers, therefore the advertisement. Your name is john Robinson, you are twenty-six years of age. Your height is five feet eleven inches. You weighed yesterday one hundred and eighty-three pounds. You have a smattering of the law and a splendid education; you have a will of your own and are handsome, you are a good conversationalist and enjoy the most perfect health. You have traveled and have but lately returned from the islands; you have but very little money, almost broke, in fact, and you need work. Is not all this true?"

"Most true, doctor," I returned. "I had no idea you knew me, or perhaps—Hendricks?"

"No," he broke in. "Neither. I never dreamed of your existence until yesterday. Didn't know Hendricks was living. Furthermore, just for the fun of it, when you dressed this morning you were minus one sock and did not find it until after you had searched for it for fully ten minutes."

I laughed, for he was telling the truth, though how he came to know I couldn't make out.

"You surely have got me, unless you are another Sherlock Holmes and a past-master of deduction."

The doctor raised his hands imploringly. "Please don't," he said. "Please don't. Not that. It's too puerile, too common. I have read Sherlock and admire the work; but I am, I hope, far above that. I have powers, Mr. Robinson, I will admit; but I am no detective. I never use deduction. Leave that to the mortals."

As he spoke he drew himself up in a proud, isolated sort of way. and I could not help but admire him, though his manner was mystic and his words, to me, rather confusing.

"That is very good flesh, sir. Very good flesh!" He stepped over to my side and to my wonderment began pinching my arm severely. I don't know why, but I drew away with much the same feeling as a fat chicken might have, and was not a little angry.

"It is," I answered, reddening. "Perhaps I had better be going."

"Oh, no! Mr. Robinson. Not at all. Please don't be offended. I meant no harm. I was just wondering how it seemed to be young. You are so vigorous and so full of life that I envied you. But I meant no harm, sir. I assure you I meant no harm."

I sat down again and accepted his apology.

"And about this position?" I asked. "You know that is the object of my visit."

"To be sure!" said the doctor. "To be sure. Well, let me see. How would twenty dollars and your board and room, sound?"

"Sounds all right," I replied; "depending, though, a great deal on how I earn it."

The old man's eyes twinkled and he smiled. "You will earn it, sit, by doing nothing. Absolutely nothing."

"Rather easy," I answered. "But there must be something for me to do. Even sleep is work when you are paid for it and you've got it to do whether or no."

"To be sure! To be sure! Well, we'll amend that. There will be work and it will consist in playing cards, reading, and conversation. You see I'm lonely, I'm getting old. I need a companion and intend to have one. I am wealthy and can afford it. It's merely a whim, sir, merely a whim."

He took an eraser from the table and began tossing it in his hand.

It all looked good to me. He was a character beyond doubt, and his personality attracted me. I foresaw that I would enjoy myself in his company. Here was someone to observe, someone to study; and perhaps a little risk. He was a man with some power, unknown perhaps, and might bear watching. That, however, was an attraction, rather than an obstacle. I would have had it just so. Therefore, we quickly came to an understanding and I agreed to remain.

CHAPTER III

THE CASE OF ALLEN DOREEN

MY POSITION turned out to be an excellent one. There was practically no work, merely to listen to the old gentleman, a task which I found not only interesting but agreeable. In the morning, usually between seven and eight, we had breakfast, after which we read and discussed the newspapers. About ten we would go for a short walk and make a few purchases until noon, when we had lunch.

From that time until three my time was my own, while the doctor retired to his laboratory, or sanctum, into which I was never invited, and none was allowed to go. This was something easily accounted for. I figured that anyone who would willingly devote his life to disease, drugs, and chemicals had all the license in the world to be queer and particular in his habits, and let it go at that.

About three the doctor reappeared, tired and nervous, and ready for a game of cards, Always at this time of day I noticed a hungry, longing look in his eyes; but this I took to be merely the effect of some strain on his mind, some scientific fact sought for but not attained and in no way connected it with myself. From three until dark it was the same thing day after day; cards, conversation, and reading. Rather a snap, don't you think?

So the days went by one after another. Each week my check was in hand and each week my savings mounted higher. One day during a walk the doctor and I ran across Hendricks. Of course, I had to introduce them. The doctor seemed pleased to meet him and he to meet the doctor.

I noticed when they shook hands that they gazed squarely into each other's eyes and laughed; they seemed to see clear through each other and to take pleasure in the accomplishment. Just before we separated Hendricks took me by the arm.

"Rob," he said, "can you come down to the office? I must see you."

"Certainly," I answered. "This afternoon if you like. What's it about, Hen?"

The doctor had been studying a window display; but just then he happened to turn and once again he and Hendricks gazed full into each other's eyes, and once again they laughed.

"Well!" snapped Hendricks. "Here's my car. I must be going. Glad to have met you, doctor. So long Rob."

And a moment later from the platform of the car he shouted back through his hands: "Important!"

We stood for some moments on the curb watching the car jolting down the street, until the fog settling in, we were left alone in the blanket of mist, gloomy and silent. Somehow I felt like the weather, cold and monotonous and dreary; my life was without sunshine.

"That man," said the doctor at length, "is dangerous."

"What man!" I snapped, turning suddenly on him. He started and eyed me curiously.

"Why, that man, of course, the one we just left. Hendricks, of course. What other could I mean?"

Now I liked the old man immensely; but I could and would not stand there and see him abuse my friend.

"Look here, doctor, you may be a learned man all right and all that, and you may know a good many things unknown to the rest of us poor mortals; but that won't help you one whit, when it comes to judging men. I have known Hendricks practically all my life and I know him almost as well as myself. He is honest and fearless and the best friend that ever trod on two feet. I will not hear a word against him!"

My companion smiled good naturedly.

"Whom are you working for, Mr. Robinson?"

"For you."

"Whose money are you drawing?"

"Yours."

"Well, then, I want you to have nothing to do with Hendricks. He's too analytical, too dangerous. I want you to leave him alone."

I was going to answer him with heat, but just then our eyes met and I subsided. For the life of me, I could not tell why; but a complete change came over me. I instinctively felt that the doctor was right and I was wrong.

Lunch was ready when we reached the house, and after the meal the doctor as usual disappeared in his sanctum. Left to my own resources, I began to come to myself.

"Pish!" I exclaimed. "I'll go see Hendricks!"

In the hall I met the housekeeper. She was dusting some furniture. I had just placed my hand on the door knob when she touched me gently on the shoulder.

"Mr. Robinson."

I noticed that her voice was low and cautious with a sort of appeal in it.

"Well, what is it?"

She lifted her kind old face to mine; her eyes full of tenderness and entreaty and I thought of pity.

"Don't you think you had better go away and stay? It's getting to be that time of the year. You don't know what you are doing or where you are going, I have been watching the doctor. I am sure the time is at hand. You are young; you are handsome, full of life, and strength. Oh! It is not fit to be so! Do say that you will go!"

She seized the lapels of my coat in her hands and looked up into my face.

"Do say it!" she repeated. "He would kill me if he knew I had warned you!"

Just then a door creaked or a window was lowered. I know not what exactly. The woman drew back, her whole form rigid with fear. We both listened. For a moment we stood like two silent statues, alert, but hearing nothing.

"Pshaw!" I said at length. "It is nothing. Now, mother, what is the trouble?"

The sound of my voice restored her and a little color came to her face.

"Go!" she said. "And be sure to remember what I have told you!"

With that a door opened and she disappeared. As for myself, I put on my hat and started for town. A half hour later I was in Hendricks' office.

"WELL, Rob," he said, lighting a cigar, "you got here. Do you know I would have wagered a good five-dollar bill against a single unroasted peanut that you would never have made it! And I'm mighty glad you are stronger than I thought. I suppose you know what you are up against!"

Now this was a line of talk for which I was scarcely prepared, especially from Hendricks. Of course, I was some worked up after the little scene with the housekeeper; but I hardly expected to find my friend in the same humor.

"Oh, say," I cut in, "are you and the old lady in cahoots? Do you want me to lose a good thing? What's the matter?"

He thought a while, went to the window and watched the traffic in the street. Presently he turned about and in his slow, earnest way began to talk.

"Look here, Rob. The gentleman to whom I was introduced today has interested me more than any person I have ever met. He is a character I have dreamed about. I have often pictured myself meeting an individual of this species. I must say it pleases me, though I am sorry to find you in his company. I intend to give you fair warning. I shall tell you what he is, and you can direct your future actions accordingly. But first I want you to tell me all you know about him and what has transpired since you have taken up your position. Go ahead."

Kind of a poser, wasn't it?

But I had confidence in Hendricks. Of all the persons I had ever met, he was the last to take a dramatic posture. I knew him for a deep water man, a man of deep thoughts and few words; but when the words did come they were like chips of steel, sharp and to the point. Therefore, I opened my heart fully. I related to Hendricks all that I knew, also I told him of the old lady's actions and the scene in the hallway.

WHEN I had finished he smiled and began drubbing the desk with his fingers.

"And what do you make of it?" he asked.

I threw up my hands.

"You've got me, Hendricks. There's a rat in a hole somewhere; but I am not cat enough to see it."

"Well," he answered, "I am. The man's a ghoul. Ever hear of a vampire?"

"On the stage."

"Yes, and off. Not the thrilling, entrancing kind that lulls you with a scene of love and beauty and soothingly imbibes while you are in a dream of the seventh heaven; but the real stern, genuine, reality. The kind that measures and weighs every movement of its victim, the kind that watches with the pulsating eyes of a cat every play of the muscles, every flash of emotion until, secure of its prey and sure of the moment, it feeds its greed with the blood of its fellow."

"Pleasant prospect surely," I answered.

"Do you still wish to retain your job?"

"Why, old boy! If that old duffer made an offer to harm me I'd strangle him with my thumb and little finger!"

"You'd do nothing of the sort. That old man has mind. Your strength and muscle don't amount to a row of shucks. When the time comes," he snapped his fingers, "there'll be no Jack Robinson."

"I suppose he will make a sort of salad of me; or serve me up as a soup," I put in.

"Hardly that. Listen, Rob. Did you ever hear of Allen Doreen?"

"The man who walked into a London cottage and disappeared from the face of the earth even though the place was surrounded by watchers? I've heard of him surely. And I believe the story a lie."

"Well, I don't," snapped Hendricks. "The man who had charge of those watchers was my own father. He was Allen Doreen's best friend. Furthermore, when Doreen entered that house, there was a man sitting in plain view of the watchers; and that man was the exact counterpart of your doctor friend. In half an hour they had both disappeared.

"When they broke open the house it was searched from cellar to attic and from attic to cellar back again; but neither skin nor teeth nor hair was found of either. The place was completely surrounded; yet no one was seen leaving the house. It was as if they had dissolved in air, so completely was it done. That was the last ever seen of Allen Doreen. My father worked on the case for years. The police of London never quite gave it up. Yet it is a mystery today—no evidence whatever, no sign, no clue."

"Perhaps," said I, "a secret passage."

"The place was torn down three weeks afterward," Hendricks returned, "the foundations were torn up for a larger building. Such a thing would have been found. There was none."

"Well," I yawned, "you've got me. Anyhow, I'll hold my job. It's the most exciting way of doing nothing I've yet found. Besides I've started on the serial, and I'm going to see the next chapter."

Hendricks took a fresh cigar.

"Well, that settles it, Rob. You're the same old daredevil. Nothing can frighten you, not even a real, genuine, live bogey man. And I'm glad of it. We'll see the thing through. Between you and me, I think we'll catch the fox and know his game. Likewise there'll be a solution of Allen Doreen.

"So far your cases are parallel: soft snap, nothing to do, pleasant doctor, advertisement, height, weight, and measurement all agree. All we've got to do is change the results. That's up to us. Now I'm going to show you something."

From a drawer in his desk he drew out a small old-fashioned case which he unsnapped and passed over to me. It contained a photograph.

"Perhaps," said he, "you have seen someone who looks like that."

I took the picture and held it to the light. It was the doctor.

"Looks like it, doesn't it," asked my friend. "And perhaps it is. That is the man who did away with Allen Doreen. I am the exact image of my father. He recognized me at once. Now you see why we laughed in each other's faces. It was a challenge, Mine was a laugh of triumph; his, of derision and contempt. We shall see who is the fox. And now, to get down to business what is it that you propose to do?"

"Well," said I, "I see nothing else to do but to return to my work and if anything unusual or threatening occurs—why, I'm the very little boy who will put a stop to it."

"I'm glad," Hendricks smiled, "that you are so confident. However, I am going to take a few precautions, or rather, I have already taken them, Your house is even now under surveillance; there are three detectives of my own hiring on the watch, one each in the houses adjoining and one in the house across the street. They know fully what an important case they are on, and are aware of the consequent glory, if they are successful.

"They are the shiftiest, nerviest, and cleverest of the force and understand perfectly with what a wise old fox they are dealing.

"Now if anything very unusual should happen, and you wish to notify the outside world, all you have to do it to place a piece of paper in a window where it may be seen, and if you need help, two—one in each end of the window. Myself, I shall keep hidden. The old fox is onto me and consequently I shall keep out of sight until such time as I am needed, when I will be there."

"All right, Hendricks," I said, "I'll do as you say. But really, after all, I don't believe the old doc is as bad as you say. There must be some mistake. I have an idea it will all come out right and the only thing to result will be a little foolish feeling for ourselves."

There was an embarrassed pause.

"As you will, Rob," shrugged Hendricks. "Only I wish to take no chances. You have a perfect right to your own opinion."

CHAPTER IV

MRS. GREEN MAKES AN EFFORT

"BACK again?"

It was the doctor; he met me at the door, a smile on his face and his hand extended; he was in his best humor.

"Yes," said I, removing my hat, "I had a little business to transact and thought it was best done before it was too late."

"That's good!" returned the doctor, a twinkle in his eye. "Always keep your affairs in good order. Everybody should do that. Neglect nothing. That's been my motto, always and at all times. We know so little of what is going to happen."

At that moment I would have given I know not what for a more definite knowledge of what the next few days might have in store.

If I was uneasy, I think I carried it off quite well and I don't think the doctor had any suspicion. In a few minutes I was my own self and was dealing out the cards as deftly and easily as ever I had done.

"This is a fine game," said the doctor, who was winning.

"Splendid," I returned inasmuch as I was paid for losing. "Splendid!"

Swish, swish, swish; the cards glided over the table—the doctor's. I dealt myself three. Swish, swish, swish—the doctor's; clip, clip, clip—our hands were dealt. The first trick was the doctor's and his smile grew broader. The next was mine, and the next, and the next; the whole hand in fact. With the turn of luck his good humor vanished.

"A rum hand," he muttered. "Gimme something good!"

However, it was his own deal, and he surely treated himself well. All the trumps were his, likewise the tricks. His good humor returned.

"Do you know, my boy, I always like to win on this night? This, you know is the twentieth of September, the night of all nights. Every twenty years it returns."

He was watching the cards as they glided toward him, picking them up, one by one, with his long tapered fingers, and talking more apparently to himself than to me.

"Every twenty years! I have reduced it to a formula, a science. Twenty years, two minutes, fifty-eight seconds!" He drew out his watch. "Fifteen minutes of eight. Over two hours yet. Two hours and over."

He began playing again—silently—a smile on his lips, anticipating. It was a sort of sensual smile and I noticed an odd look of anticipation in his eyes as he watched the cards. The tricks were all his and he drew back entirely satis?fied.

"What's this, doc? Why every twenty years? Why must you win tonight? Experiment or fact?"

"Fact," answered the doctor, "fact. I win for luck; luck always goes with the winner. You lead."

Again we went to playing; but in the intervals of play I began, absently, like one merely passing time, to roll a newspaper which was lying on the table. You may think I was perturbed; but I was not at all; I was merely doing what my friend had advised—playing safe.

If I were going to see the thing through to the end, I calculated that perhaps at little help at the climax would be a thing most convenient. Of course, my mind was working. Hendricks had called the doctor a vampire. I had never seen one: but my imagination had pictured a thing vastly different from this.

During the silent moments I watched him—cool, clear-eyed, and kindly, his every movement an act of grace, his whole manner the embodiment of fascination. When he smiled the very atmosphere seemed to ripple, his clear eyes fairly danced with mirth and you felt a sort of infinite joy in the mere privilege of sharing their pleasure.

I had known him for many days—this man, and during all that time I had found him nothing but kindness and consideration, a companion, jolly at all times. As I studied him and watched him, my mind revolted at its own folly.

What a climax of things ridiculous to classify this man with a species of moral outcast, which mankind in its loathsome horror has refused a classification with either man or beast. Can you blame me for laying the paper back on the table? I had only folded it.

THE game continued, the doctor winning regularly and deriving an infinite joy therefrom; and I, with all I had on my mind, watching him intently for ever so small a sign that might signify or prove him to be anything but that to which he pretended.

The clock struck nine. It came all at once as clocks have a habit of doing when, in the silent hours. a clashing that seems to step right out oi the wall seizes you by the throat, and startles you out of your marrow. We both started; but the doctor, I was sure, was really frightened.

He half rose in his chair, seized his watch in his left hand, and stood gazing from it to the clock in a sort of palsy. A look such as I never saw in a mortal came into his eyes; they fairly danced and glittered, and as he gazed at me bewildered, I would have sworn that they dissolved, and that I looked not into the eyes of one, but into those of a hundred.

Snap. The doctor closed his watch.

"My!" he sighed. "How that did startle me! I thought it was ten and I was too late. Let us have some wine."

He reached for the bell and pressed it energetically, almost savagely.

"Do you know, Mr. Robinson," he asked while we were waiting, "do you know what it means to me?"

"Naturally I do not," I replied. "You having never told me."

"Well, I'll tell you"—leaning back in his chair—"it means this: In an hour's time I shall be either alive or dead. If my experiment or fact, as I have called it, is a success you will see me a miracle, alive, young, strong, handsome, a being to marvel at and admire. If it should fail, you will witness the most abject and miserable death that ever has been or ever will be seen on this earth.

"In a few moments from that time I shall begin to dwindle, to tumble, to struggle, to cry out; my pleading will ring in your ears for years to come; when you are dreaming and when you are waking you will see my fearful image; I shall be a horror and an abomination to you. In a few moments I shall be no larger than this inkstand, and I shall be growing smaller and smaller until at last I disappear—a mere speck of nothing forever and forever.

"But you, who are standing here—you will have seen an army, a strange fantom host, jabbering, incoherent, indistinct, a confusion of the ungodly with the godly—a babel of conflicting tongues, a struggling of opposing nationalities, a maelstrom of fantom hatred, with myself the center of it all, reviled, execrated, loathed, and despised. Their curses will ring in your ears for a lifetime.

"I will stand here alone; they will vanish; one by one they will step into a grave of shadows and disappear, and you will be left alone with nothing but a problem, the solution of which will baffle not only you, but your friends and assistants for all time."

He was quite cool now, and I could see that he was perfectly sane, although my firm faith in his manhood—the good old gentleman kind—began to flicker perceptibly.

"And it was for this," I asked, "that you employed me?"

"Exactly."

"You wished to make use of me?"

"Naturally. For what does one man hire another if it is not his services? You will help me in this crisis. It will be a triumph, a great one, for one or the other of us. In any case you will have beheld something to witness which there are many who would willingly pay a fortune."

The door opened and the housekeeper brought in the wine and the glasses. I bowed to her and took the occasion to nonchalantly place the roll of paper in the window; the curtain was up and I was fairly sure that it could he seen from across the street. My action I was sure was not noticed, for the doctor was pouring out the wine, while the woman was standing alongside the table watching him.

Evidently she was greatly excited, for I noticed that her hands trembled violently, while her face, so calm and healthy usually was ashy white, to which her lips drawn down at the corners as if from some load of anguish, gave that troubled and stricken look of one standing under an impending disaster.

"Mrs. Green"—it was the doctor who spoke—"do you know the day of the month?"

It was said in a cool, steady tone, but there was mockery in it indescribably; an indefinite taunting, tinctured with hatred and self-superiority.

The woman started and her hands clenched; a very storm of fury broke upon her. If the doctor had wished to goad her to madness, he had done it well and with but a sentence. Anyway, it seemed to please him, for he smiled sweetly while she broke upon him.

"You!" she shouted as she leveled her trembling, accusing finger. "You! You liar! You murderer! You dog! You know I know! And you dare ask me! What day is it! What day of the month is it! Yes, ask, when you know so well! It is the twentieth of September, that it is! Your anniversary! Your celebration of crime—of murder!

"Where is Allen Doreen? Down in your black, black, dirty, warped, crime-bespattered soul you are gloating over a murder this very night! Where is Allen Doreen? Was I not with you twenty years ago when you murdered that poor, innocent lad? And because I did not witness the actual deed, do you suppose for an instant that I doubted your guilt?

"I am your housekeeper now and I was your housekeeper then, though you little knew it when you engaged me six months ago! Why did you hire Allen Doreen? Why did you pay him fabulous sums to do merely nothing? What became of him? What did you do with him? Answer me that! Why have you this man here? Sir," she continued, turning to me, "unless you take my advice and leave this house at once, you will never see daylight again."

"Mrs. Green! This is enough! Enough!"

And before I could interfere he had seized her by the arms and ejected her from the room, turning the key in the door as he did so!

CHAPTER V

THE VAMPIRE

HE WAS a man of quick action, and it was done in a twinkling, almost before I could think.

But the scene had decided me.

The picture of the old woman standing there in the lamplight, her face ashen, her eyes flashing, and her accusing finger speaking as loudly as her tongue, will ever live in my memory.

And I can see the doctor still, sitting there with the wine-filled glasses, smiling cynically, egging her on with his mocking, taunting laugh.

I would have rolled a second paper and brought Hendricks and his men thundering through the door, but for a thought. I was morally sure that this man was a murderer, and I was just as certain that he was contemplating another crime this night, with myself for the victim.

But what was the proof?

I had none; only an old woman's word, and that had all been before the law already. I could not call Hendricks yet. If I were afraid, I could walk out of the door. The doctor could not stop me. But I was not afraid. No, there was but one thing to do—to wait. When the time came I would throttle him with my thumb and finger just to show Hendricks: and then call in my friends.

The doctor was in an apologetic mood, though I noticed that he put the key in his pocket. Not that I cared, for I considered myself enough of his master to take it away from him whenever needed, only I noticed it.

"You mustn't mind her," he said. "Mrs. Green is a good old soul, only a little erratic, that's all." He pointed to his forehead to signify her fault. "She has them once in a while. She lost a dear friend once; but the poor old soul has a haunting idea, of which I can never rid her, that I was the cause of his disappearance. She has been my housekeeper for years. She is splendid. Let us get back to our game."

Once again we sat down, sipping the wine and playing cards. The clock above was slowly ticking toward the fatal ten, and the doctor was having all the luck. I was very curious and expectant; but kept a cool head, watching every movement of my companion.

What were his plans? What his treachery? What his preparations? I could see none, only his everlasting playing.

He seemed superbly confident, humming a low tune. and smiling as buoyantly as a boy of twelve. There was surely something in the air; but try as I might, I could make nothing out of it. I waited.

It was half past nine—twenty minutes of the hour; the room was hot and stuffy, and I began to feel nervous. I had no fear, and, having none, I tried to laugh at myself for giving way to nerves. In spite of all my efforts, I felt myself slipping, a great lump came in my throat which I could not down. and I could hear my heart thumping against my ribs, pulsating so loudly that I was rather surprised that the doctor did not notice it.

Fifteen minutes to ten. I was watching keenly.

"At your first move, old man, I will strangle you," I said to myself.

But the doctor did not move. Instead he kept on playing, calm, happy, and in perfect good humor. His very coolness nettled me; from dislike I was rapidly running into hatred. My hands shook with desire for action. If he were a vampire, I wanted to know it, and to know it quickly!

Why this everlasting delay and these infernal cards?

I was cutting, when the first sign came, and I shall never forget it.

It was a sensation, a feeling I wish never again to experience. For the first time I knew that I was playing with a power behind the conception of man; that I was eating with the devil and was using a short spoon. It was like a wave; my courage vanished and my confidence was gone. When I looked up the doctor was peering at me.

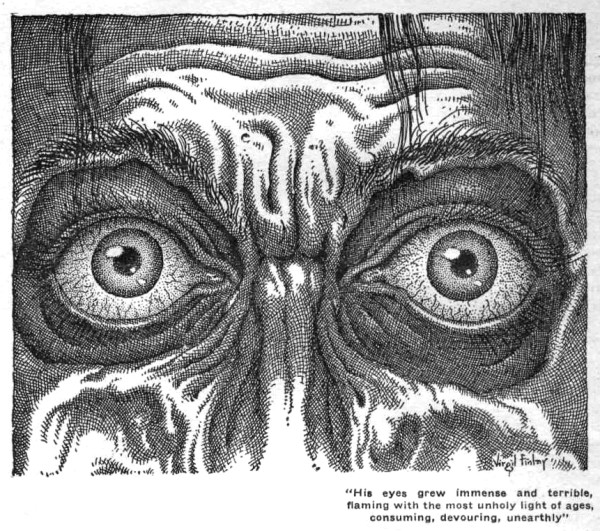

Lord, what eyes! Cavernous, flaming with the most unholy light of ages! With a cry of horror I dropped the cards.

The doctor said not a word; his whole body seemed to shrivel and become head and that in turn to transform and disintegrate and to slowly reform and grow into eyes, immense and terrible, two great green fires, consuming, devouring, unearthly.

What was it! What was it! A scream!

The eyes vanished; the doctor was sitting there before me. Yes, it was a scream; a woman's scream. How good it seemed! A door slammed across the street; there was a scurrying of feet. I was myself. I seized the second roll and started for the window.

"Put down that paper!"

It was the doctor who spoke. The clock stood two minutes to ten.

"Put down that paper!"

I laughed.

"I'll do nothing of the sort! Stop me if you can!"

In a flash he was at me. Here I knew myself his master. Arms outstretched he made for me and I could not help laughing at his awkwardness. Timing him to a dot, I let drive my left. It was a well-directed blow, and I knew it for a knockout. He was coming head on when my blow landed.

Landed! Say, rather, entered, for my fist entered his jaw like so much mist, passed through his head and out the other side.

Unable to believe my senses, I shot out my right. It passed clean through him. I could see my fist out of his back.

With a cry of horror I sprang out of his reach. I could hear voices; someone was forcing the front door.

"Hendricks! Hendricks!" I screamed.

The old man was after me like a demon.

"Aye, Hendricks!" be mocked. "Hendricks! I fooled the father and I'll fool the son! Every twenty years I eat a man, and I'll eat you as I have the others! Give me that paper!"

He made a lunge, and before I could sidestep he had me. I struggled, but it was useless. It was like fighting with smoke. I knew I was gone; I was helpless. My friend was outside.

But he was too late.

HERE Robinson lit a cigar.

"Well," I asked, "what happened?"

He puffed for a moment.

"Hendricks will have to tell you the rest; my part is done. Go ahead, Hen, and give him the other part."

Hendricks took up the narrative as follows:

CHAPTER VI

WHAT HENDRICKS FOUND

WHEN Robinson left my office I was extremely puzzled.

My friend would do his beat, and if the old fox caught him unawares, well, then, he was a slyer fox than I imagined.

Of the man himself I was morally certain. I returned to my desk and studied the picture over and over again. They were the same, barring only the difference in the style of the clothes, which, of course, counted for nothing.

There was one thing, and one thing only, which bothered me.

These two men were of the same age; yet this picture had been taken over twenty years before. Surely the living picture-the man himself—should have aged some in that length of time, or was he one of those upon whom years had no effect and whom advancing age always finds at middle age, stationary, healthy, and belying their own looks?

The telephone rang.

"Hello! Hello! Who is it?"

"Is this Mr. Hendricks?"

"It is. Who is this?"

"Brooks, at Rubic Avenue. We have had the house under surveillance ever since you detailed us. Mr. Robinson has just returned. The old lady—the housekeeper, the woman you mentioned—was just here. You are right, all right. She was mixed up with the Allen Doreen affair, and I think she will be our main witness. I want you to get out here and have a talk with her.

"And, by the way, the old lady says that this is the day, and we want to take no chances.

"She has gone back to the house just at present; she is mortally afraid of the doc, says that if he rang and found her gone he would surely kill her. 'When can you come?"

"Right away. I will be out there immediately."

In a few minutes I was on a car bound for Rubic Avenue.

My men I found in the house across the street, which they seemed to be making their headquarters. It was now five-thirty.

"Well," said I, "what news?"

"Not much of anything," said Smythe. "But we are awaiting the woman; she promised she would return as soon as you arrived, so we could settle all our plans. She says there is no danger until some time after nine, absolutely none, because the doctor, as she calls him, never works at his trade, or whatever you may call it, in the daytime.

"Brooks, who is on the watch, reports that Robinson and the doctor have just entered one of the front rooms upstairs, and, from the looks, are playing cards."

"Very likely," I answered. "Robinson, who has just left me, says that is their chief pastime."

Then I told them about my interview with Robinson and the plans we had laid. "So, you see, our best tactics will be to wait and watch."

Well, sir, we waited.

About six came the old lady. She was terribly excited and very much worried; but beyond a recital of her former experience and the fact that she had heard the doctor mumbling, "The twentieth, the twentieth," several times during the past few days I can't say that she had much information to impart. But on this one thing she was very sure and very much worked up.

"Oh, how glad I am that you men are here to help Mr. Robinson!" she said. "Only I'm afraid, terribly afraid! Perhaps you are not smart enough. Oh, he's clever; it will be just like him to do his work right in front of you, and you not be able to do a thing."

"He would have to be a devil to do that," said Smythe. "I suppose you know that the house is surrounded, and that nobody can leave it nor enter without at least ten eyes upon him."

"I know it, I know it," said the old lady. "But what's been done before can be done again. 1 tell you for myself I ain't afraid, he won't harm me; but I do care for this young man. He won't listen to me. Says he's not afraid and all that. But I tell you all quite frankly, doctor's not human. No, sir, he's something else; when a man can do what he does, he's something, and that ain't man either." With that she left us.

There was a good deal in what she said, and I told them so: but Smythe shook his head.

"I've heard of this Doreen case before, Mr. Hendricks, read of it, and I have always said I would have liked to have been there. Now, here's our chance. We have Robinson over there, big and strong, athletic, no fool and no coward, and we have a bunch of men around us, all of them trained, all alert; and we have Mrs. Green there in the house with them, and a code of signals. Everything is in our favor. We can catch the old fox red-handed, save Robinson, and clear up the Doreen mystery, and all at the same time."

WE ALL of us settled down now to our vigil. From our vantage ground of an upper room we could look across into the room where, sure enough, sat Robinson and the doctor, both apparently enjoying way up to the room. You'll have your a friendly game of cards. It was not too close nor yet so tar but that we could make them out quite plainly; the curtains were open and, of course, a great deal of the room was in our plain view.

Well, nothing happened. The minutes drew into hours, and as the first excitement wore away the time began to grow lazy. I began to get sleepy. I think it was some time after nine when Brooks nudged me.

"Look! Look! What's Robinson doing?"

Across the street I could see Rob. He was rolling up a paper.

"Was it one or two?"

I got up; but he seemed to laugh and lay it down again, and to resume his playing. Nothing more happened for about a quarter of an hour; then suddenly the old man started from his chair, pressed his hand to his forehead, and in a startled way began to talk to his companion. A few moments later, after he had resumed his seat, the door opened, and we could see the old man and the old woman shaking their fists angrily at each other—at least the old woman shook hers. Then it was that Rob put the paper in the window.

"Ah!" exclaimed Brooks. "Now there is something doing over yonder! What'll we do?"

"Beginning to be interesting," I answered, getting up. "You stay here, Brooks, while I get the men together. Keep a close lookout. If Bob gives the other signal or if you see anything suspicious, be sure and signal to us, and we will break in immediately."

Below I gathered up the men, placed two at the back, two at the sides, and kept with me two others. Every inch of the house was to be watched. The light was at the window, and the house was silent. For some time we waited; but there was only the thumping of our hearts and the everlasting pulsating throb of the city night. After a little a window was raised, and I heard Brooks' voice.

"Hendricks," he said coolly, "now is your time. Enter quietly and make your man easy enough."

I had just reached the steps when a woman screamed, and a frightened, fearful cry it was, to be sure. And then, running and almost falling, I could hear someone coming down the stairs.

With a cry we made for the door; but at the same instant the housekeeper opened it, slammed it, and stood before us. She was white and trembling.

"Oh," she cried, "for goodness sake, hurry! Hurry! It's the devil! Sure, sure it's the devil!"

"Woman," I almost shrieked, "look what you have done! We are locked out!"

"Burst it! Burst it open!" came an order behind.

It was Brooks.

"Hendricks! Get in there! Get in there!"

With the force of two hundred pounds he landed against the door, and in a minute we rolled, men, door, locks, and all, a heap on the floor. The woman screamed again, and above everything I could hear a voice familiar and distinct. It was Rob.

At a bound I threw myself to my feet and dashed up the stairs. A light was streaming beneath the door, and there was a peculiar noise coming from the inside, a sort of chuckle. Brooks passed me, and both together we landed against the door. It was locked; we knew that, so we sent it crashing to the floor.

The room was empty!

CHAPTER VII

VISITOR OR VISITATION

WE WERE baffled, defeated! I had been laughed at to my face! My best friend was gone!

A sort of haze came over me, and for the next few minutes I remember almost nothing. Then I noticed the blaze of light, the cards about the table, the empty wine glasses and bottles, and the soft green carpet, while I could see Brooks dashing about the room, stamping on the floor, pounding the walls, and swearing a great, copious string of heavy oaths.

"You below, there!" he shouted. "Are those men here yet? Well, hold tight! Don't let an inch of this house escape you! I'm going to comb over it with a fine-tooth comb! And if we don't get him, I'll know he's the devil!"

"And that's what I think he is," said I. "I could have sworn I heard him when I reached this door!"

"And I, too," returned Brooks. "Yet here we are, and there is neither hide nor hair of him! "

But however much my detective friend agreed with me, he would not, as he said, allow superstition and mystic fear to get the better of him; and now, while he had a hand in the game and the thing was warm, he was going to see the house from top to bottom, attic, cellar, and sideways.

Keen over our lost prey, we set to work, and I do not believe there was a house searched as this one. With the help from headquarters, we went at it from every corner.

Everything was ransacked, rummaged, burst open, esamined; walls were thumped, floors pounded, ceilings tested, and carpets torn up. But it all ended as I had fore-seen.

When gray dawn struck, it found a house much like one stricken by an earthquake or a whirlwind, but never a clue that would lead us anywhere at all. Of course, I was heartbroken over Rob, and I swore by everything that I knew that I would never leave off the trail until I had either rescued or avenged him. Nor was I alone.

Brooks, with all his great confidence and splendid nonchalance of a few hours before, was a thing to look at. Truly he reminded me of a bloodhound chasing his tail. With all his skill and technique he was getting nowhere. When daylight came he threw up his hands.

"I tell you, Hendricks, this is not a case; it is a study, and I must have time to think. Likewise"—remembering himself—"I must eat. But I tell you one thing; I will never leave this case until either I or the doctor get each other."

Anyway, we ate. And afterward we returned and began our search all over again. And we kept it up day in and day out, and to be doubly sure, we rented the place and moved into it. And we watched and waited, while the days grew into months, and the months into years, until I found myself five years older with a great practice and a greater mystery.

I HAD attained by hard, grinding work, I think, a very credible place in the legal world. I was not married, and was living with Brooks in the House of Mystery, as he chose to call it.

We kept a housekeeper—none other than the old Mrs. Green, who had held the same position under our spooky friend the notorious Dr. Runson, for whom the police of every city of the world were looking and not finding.

There was one great, permeating idea in the house; find the doctor, avenge Robinson, and clear up the Doreen mystery.

Brooks worked on the case as one who would work on a puzzle. He was always ready: had had the police oiled and ready, prepared at any moment to reach out and grasp its victim.

Then one night we received a sign. At the time we had moved into the house I had chosen a nice cozy room to the rear, and would have made that my sleeping quarters had it not been for Brooks, who expostulated in the loudest manner.

"There is but one room in the whole house, Hendricks," he said, "in which we can sleep, and that is the little room up yonder to the front, where this little scene took place a few weeks back, and there we'll stay."

I remember plainly. It was in September. I had been out to a social affair, and did not get in until about eleven o'clock. When I turned on the light, Brooks was snoring loudly, his head back and his mouth wide open, as though he were enjoying it. I crawled into bed with him.

How long I slept I do not know; but when I awoke some time after with a start, it was to find Brooks, or at least I thought it was he, sitting on my feet. Like any sleepy person, I became angry.

"Hey, you! Gee whiz! Brooks, get off my feet!"

Someone at my side turned, and I saw it was Brooks.

"What's the matter with you?" he said. "I'm not on your feet. Got a nightmare?"

But I was not asleep, and I knew it. There was surely something on my feet, so I raised up and looked. Sure enough, seated there in the moonlight was the form of a man.

It was Robinson!

For a moment I was dazed, my heart jumping and my throat swollen.

"Don't you know me, old boy?" it said.

Hardly believing my own eyes, nor my ears either, I dropped back on the pillow and lay thinking. Finally I reached over and pinched Brooks, who was almost awake.

"What's the matter?"

"Do you see anything?"

"Where?"

"At the foot of the bed. On my feet."

"Pooh!"

With an air of disgust and distrust, my bedfellow raised himself and immediately dropped back on the pillow.

"Who—who is it?" he whispered.

The sound of his voice, and the fact that he, as well as I, could see some one, reassured me; for, though I am hardly afraid of flesh and blood in the real personal form, I, like most other people, have only a creepy sympathy with an apparition. That Brooks had seen and recognized was an assurance I needed, for I must say I was in a cold sweat of fear and apprehension. I raised myself to a sitting posture.

"Well?"

It was Rob who spoke, and it was the old voice.

"Is this really you, Rob," I asked doubtfully, "or just something else?"

He laughed.

"You think me a ghost, don't you, Hen? Well, to tell you the truth, I am, almost; at least, as near one as a man could get."

"Then—then you are not dead, Rob?"

"No," he answered, "I'm not dead, nor alive either, for that matter."

He got up and walked about the room, and I noticed that his walk was ghostlike, no noise, absolute silence, and he nearly six feet and one hundred and eighty pounds.

"Look here, Hendricks." He stopped to look at the clock. "I've got but a few moments to spare. It was only by superhuman struggle that I am here; only by a terrific battle of the will that I am with you; and at any moment, any second, I may leave you. I came to help you, to encourage you. Keep up your search, and some day you will be rewarded.

"I will help you. I am not dead. Far from it; I may live forever. Keep your eyes open at all times and watch personalities. I will try to lead them your way. Only be prepared when the time comes. You were right about the doctor. He was a vampire. I found out when it was too late. If you watch and work hard enough, I will have a chance to die even yet."

He stopped beside the bed and looked at me longingly, his eyes filled with a yearning that was piteous. My mind was in a whirl, and my heart was beating like a trip-hammer; but in the midst of it all I had presence enough to analyze his features. The eyes were the same; the hair, the jaw, and the peculiar expression of the mouth were all his; beyond a doubt it was Robinson.

I remember the wild joy that surged through me at the certainty. I reached up to grasp him, but he drew back.

"Don't, Hen! Don't! Not now!"

He drew back; for, not to he denied, I had sprung out of the bed and was pursuing him with outstretched hands.

"Stop!"

But I would not. Instead, I followed him across the room with my hands reaching out for him.

"Well, then, if you must have it! Good-by!!!

There was a good deal of the defiant in the words, and yet a world of misery. And with that he disappeared, vanished through the solid wall as though it were the open air.

CHAPTER VIII

PANDORA's BOX

OF COURSE, we dressed and began a most thorough examination. The doors were locked, the windows fastened, and everything was found in its accustomed place. We could get no satisfaction; there was no solution but one; and as I was no believer in ghosts or their workings, I was loath to accept it.

Still, what other solution could we give? It was either that, or we had, both of us, been the victims of a huge hallucination, and we were, both of us, too much awake, and had altogether too much pride and confidence in our own intelligence to admit that we could drift off into a state so bordering on the insane as that. How, then, were we to account for it? I admit I tossed up my hands. It was too much for me.

If Rob was not dead, and he said he wasn't, how had he gained entrance to our room? Surely none but a fantom could have done that, and no one mortal could have vanished in such a complete and marvelous manner. Furthermore, if alive, what reason had he for keeping himself hidden, especially from his best friend, myself, whose help he needed, and from whom he had just now sought assistance?

I could see none. But one thing I did do. I cursed the impatient haste and unreason with which I had just acted, Had it not been for my own foolishness and lack of tact, we might have had a few good practical clues on which to work. Rob must have had something to impart, or he would never have paid us this visit, and so I reasoned with Brooks.

"Pshaw!" said my friend. "The man was murdered. That's plain as day. Who did it is the goal. The case has just begun, but I'm going to solve it, believe me. Meantime, Pm going back to bed."

Going to bed and going to sleep were two different things; so we spent the rest of the night in argument and in the consuming of innumerable cigars. And when the morning broke and the gray light of dawn streamed through the windows, it found two men with two different views. I tor the living, and he for the dead.

Which of us was right you shall see for yourself.

I WAS engaged on the Huxly case, with which you and everybody else who reads the papers must be familiar. As I have said, I had risen not a little in my profession; my practice was large, my reputation established, and, best of all, I had the name of getting most anything I went after.

At the same time, I was on a dead level with myself, and knew my limitations, even though I did not let others into the secret.

The Huxley case, you will remember, was one of those paradises for attorneys, a sea of legal entanglements wherein they could swim about to their hearts' content, breathing law, living law, sleeping law, with no way out, no exit, no escape.

I was working night and day. It was the climax of my legal career. If I won I was made, and I was going to win.

One day, while deep in the Huxly case, I had ordered my lunch and was looking over a local paper; there was not much in it, so I was running over the market reports. I don't know how to account for it, but I have always said that the great and important changes of life are prone to come upon us suddenly and unexpectedly.

And although I have always made it a habit to watch the turning up of things, as it were, it has ever been my fortune to be caught like a drowsy sentinel, asleep at the post. How little was I aware at this moment. Everything was in the routine. The world was running smoothly; so much so, in fact, that I had to satisfy my craving for excitement with market reports.

If may have been the print, or it may have been anything. I'm sure I don't know exactly. But, anyway, when I was half through the page my eyes failed me and the whole thing blurred.

"Merely a case of nerves," you say. Perhaps so. That's what I thought. I closed my eyes and pressed my fingers against the eyeballs. The pressure brought relief for an instant, and I began rubbing them. A flickering and flashing of lights clamored with myriad tattoo across my brain, and my head swam. I opened my eyes again and reached for a glass of water. The paper was still in my hand; but it was an inky black, the light of absolute nothingness, and clean across it, in plain white letters, was the word:

R O B I N S O N

"Premonition," you say. Perhaps it was. Anyway, it startled me. The moment those letters were indelible in my mind, the room cleared and my vision returned. Half startled, I looked about me.

Everything was as before; if anything had happened, nobody had noticed it. It was the same prosaic, hungry crowd, and there was the usual sound of eating, of dishes and spoons, and the quiet, soft step, step, step of flitting waiters.

Nevertheless, I was a perfect tingle of excitement; my hands shook and my heart seemed to swell up within me, to fill my throat and choke me with anticipation. Something was surely going to happen. Carefully I studied everybody in the room. Then I turned clear about and looked at the door. There it was.

It was Rob!

He was standing just inside of the door, his soft hat slouched over his eye and his empty pipe in his hand. I could see the cashier speaking to him, but he shook his head. Evidently he was looking for someone. I had half risen from my seat when our eyes met; he smiled and came quickly down the aisle. How I watched him!

"Rob, Rob, Rob," I said to myself, keeping time with his step as he came toward me. Then hesitation. The resemblance began to glimmer and fade away. The nearer he approached the less he looked like Rob. Could it really be he? How my wild hope rose and fell! When he was quite up to me I saw I was mistaken, and that he was an absolute stranger.

"Pardon me," he said, "but were you expecting me? If you don't mind, I will sit opposite you. You seemed to know me."

Know him! On closer view he seemed strangely familiar, very much like another, there was a difference and a resemblance which, added together, was indeed a puzzle.

"Your face," said I, "reminded me strangely. I took you for some one—a very old friend. And yet it could not be. I see I am wrong."

"Why?"

He looked up from the table with a strange, querulous smile.

"Why couldn't it be? Who is this person?"

A thought struck me.

"Your name is not Robinson?"

He sobered down in an instant, and began arranging his knife and fork beside his plate.

"No," he said, eying his dish; "just Jones. Ebenezer Jones. Fine name that! But suppose my name were Robinson? What would it signify?"

"What would it signify?" I repeated. "Just this. If your name were Robinson and you were the real person, whom you greatly resemble, there would be a mystery solved."

"Ha!"

My companion dropped his fork and looked up.

"What's this?" he asked. "A mystery-a real, genuine, live mystery! Have you one, sure enough? Let's have it. That's my line exactly. It's food and drink to me."

He waited; and before I knew it I was telling him what you already know. I don't know why I should have told it there in the restaurant; but from the first he seemed to have a power over me, and through it all I had that fluttering sensation and my heart kept beating "something will happen, something will happen."

"Splendid!" he exclaimed when I was through. "And have you this picture of the doctor and a picture of Robinson?"

"In my office. Yes."

"May I see them?"

"Certainly."

"Well, I would be much obliged to you. This interests me deeply. We shall go up after we eat."

In another half hour we were examining the photos.

"So this is Robinson, and this is Dr. Runson? Eh? Might have been twins but for thirty years or so. Eh! Well, I tell you, Mr. Hendricks, you needn't worry. In less than six months you will know all about it. No? You don't believe it? Well, Well! Wait and see. I have a strange power, and what I say generally comes true. Even if my name is just plain Ebenezer Jones. Now, Mr. Hendricks, I have a proposition to make. How would you like a business associate?"

He staggered me.

"Well, an assistant if you will. Call me anything you like. I will name my own terms. Salary, nothing, and as much work as you can get out of me."

I was taken back.

"Know anything about the law?"

He laughed and his eyes fairly danced with amusement. The chief justice could not have been more amused at the question.

"Just give me a trial is all I ask. I want to stay in this office until this mystery is solved; and while I'm here I want something to do. You'll find it to your advantage. I know something about law and then some. Even though my name may be just plain Ebenezer Jones."

WELL, to make the matter short, I took him in.

It was a rather sudden and strange thing to do on such a short acquaintance. I was a little surprised at myself at first, but soon found that I had made no mistake. Indeed, before many days I was shaking hands with myself.

Ebenezer settled into my office with an ease and a confidence that could only come from ability and energy; and he tore into cases with a vim that was irresistible. I had asked him whether he knew anything about the law. I was soon laughing at myself.

Was there anything about the law that he didn't know! That fellow was a veritable encyclopedia. He seemed to have it all in his head. He became the brains of the office. I might well enough have burned my books. I began asking questions, and soon quit referring to my library. I found it was useless; all I got was a verification of his statements.

Naturally I prospered. We won the Huxly case hands down, although I knew it was Ebenezer's brain and not mine that did it.

Still, I got the credit, so I had no kick coming. Other cases came our way. We won them all. It was so easy that it was amazing. I congratulated both myself and him.

"Fudge," he said. "It's nothing. There's nothing to the law but the knowing."

And I guess he was right. Anyway I was in high spirits, My reputation was bounding up. I became a boy again. Success breeds dreams; I could see great pictures ahead, if I could keep this genius at work; I would be chief justice!

The mystery?

It had grown so old that I was beginning to despair of it. I had, to be sure, a restless feeling, a sort of nervous certainty that it would be cleared up some day; but I had become so used to waiting that it had become a sort of habit; I was helpless and could do nothing, and there was only hope. Of one thing I was certain—Robin-son would show up some day, somehow; a sort of subconscious wisdom seemed to tell me that.

Was it the mystery that held Ebenezer? It must have been; though what he was going to gain by sitting in my office, or how he was going to solve it by doing nothing, I could not make out. There was only one clue, and that was his resemblance to Rob. When I questioned him about it he always laughed.

"If I were Rob, I think you would know it, Hendricks. No, no, boy, you're on the wrong track." Then, after a while, after a good many minutes of silence and thinking: "You'll have to wait, old boy. Only, I tell you, things may happen, and when they do, keep your wits about you."

But nothing happened in spite of his words.

Days wore into weeks and weeks into months, and we dug into the laws. Ebenezer was at it early and late; and I did my best to keep up with him. I offered him a partnership, but he refused it. When I tried to have a moneyed understanding he laughed at me.

"I have so much of that stuff that it nauseates me. I prefer to work for nothing and see what turns up."

He had no bad habits that I could notice, and I watched him closely. He always brought a bottle of port wine with him and drank it all during the day; that is, what I did not help him with. Also he smoked occasionally; only it was an old, seedy pipe, such as you would expect an Ebenezer Jones to smoke.

There was only one thing in his habits or possessions that could arouse my curiosity; that was a small case which he always carried with him; it was not more than three inches square and could be conveniently carried in his pocket. The first thing he did on entering the office was to lock this in his desk. And when he left at night it went with him without fail. Once he opened it quite accidentally, and I noticed with surprise that it contained two small bottles, both of them full of a liquid, and that the color was of port wine.

They say it was Pandora who opened the box. Of a certainty that mythical young lady was an ancestor of mine. I can understand her feelings exactly; they must have been tantalizing. Something told me I must open that box. Of course I revolted against the feeling; I fought it?ercely; all the ethics of my nature and training warned me and pleaded with me.

It was no use. There was still that feeling, perverse and ever there. My fingers itched, and my heart yearned for that case.

Why I should have had it I could not tell; it was a freak of my own nature or the hand of Fate. My lower self seemed bound to triumph in this one case, although my manhood and integrity kept saying: "No, no; thou shalt not."

"After all, what did it amount to?" I would repeat. "Merely a case and two bottles. Examine them and return them; no one will be harmed, and you will be satisfied."

Well, it went on that way tor a good many days, and all the time I felt myself growing weaker. It was a trivial thing in itself; but the fight I put up against it made it, with me, a matter of some magnitude.

At length I came to it. I resolved to examine the case and in this way relieve myself of this everlasting torment. It was a simple thing in itself, and were it not for its strange aftermath I would soon have forgotten it.

CHAPTER IX

TWO DROPS!

EBENEZER had stepped out of the office for a few minutes, leaving his desk unlocked. It was quickly done. I stepped over to his desk, drew out the drawer, and took therefrom the little case of mystery.

A slight pressure and the thing flew open, disclosing the two small bottles I knew it to contain. I remember wondering why the two bottles instead of one inasmuch as they contained the same liquid. But did they?

Perhaps they only looked alike. To satisfy myself I picked up one of the bottles, opened it, and smelled. It had absolutely no odor, and of course I dared not taste it. It was full to the overflowing, and as my hand trembled somewhat, a drop fell on the wineglass that was resting on the desk. I replaced the cork and was about to open the other bottle when footsteps in the hall—Ebenezer's feet—put a speedy end to my investigation.

In a minute I had closed the case and resumed the seat at my own desk.

"Hello," said Ebenezer. He placed his hat upon the desk and, taking the wine-glass, poured himself a large drink. Then in horror I recalled the spilled drop.

"Horrors! What is—"

No use for more; it was done.

At first he stood stark still, his hand raising wonderingly to his head and his eyes questioning; then his frame shook and his color began to change, first to a yellow, then to a dark green. He was the most uncanny thing I ever looked at, a being dropped from another planet.

"Mercy!" he exclaimed. "It is done!"

Then with a furious haste he tore open the desk and seized the case and vanished into the dressing-room. I could hear the lock crash as he turned the key. Then he fell; but he must have risen immediately, for I could hear someone Walking. Then a voice—no, a cry, and how it rang!

"In the name of Heaven, Hendricks, open the door! It is I—Rob! Oh, before it is too late! Hurry, hurry, break it down!"

With a cry of fury I flung myself at the door. It held.

"Hurry, hurry!" came the despairing call from the other side. Then another voice cut in:

"Shut up and come here; I'm master yet.

Something fell, and then there was the tramping of many feet. A struggle seemed to be going on, and above it all the voice of men—not two nor three, but of a multitude. In the midst of my frantic haste I could hear it. Awful, excited, despairing, the incoherent shoutings of all nationalities. German, Greek, French, Italian. And above it all the voice of a master.

"This way; this way! There now; there now!"

In a perfect frenzy of haste I seized an implement and splintered the door and, as it fell back, sprang into the room.

It was empty.

No, not quite.

Ebenezer Jones was standing at the window watching the street below.

"Why," he smiled, "you must be in a hurry, Mr. Hendricks. Do you always enter a room in this manner?"

Shamefaced and abashed I stood there, puzzled, a tool shown up in the height of his folly. I was about to become a hero; I came crashing through the door ready to grapple with a multitude, and instead I was laughed at. Humbly I drew my handkerchief and mopped my face.

"Excuse me, Mr. Jones," I ventured; "but I—I surely heard strange noises in this room."

"Strange what?"

"Noises."

"Tut, tut, Hendricks." He came over to me and laid his great brawny paw on my shoulder. "What noises did you hear?"

"Why," I said, "I heard, or thought I heard, my dear old friend Robinson. He was calling to me right in this room, begging me to open the door. And there were others—lots of them. You had the door locked, so I smashed it down."

"I see you did," picking it up and placing it against the wall. "But you didn't find Rob, did you? Nor the others? Just plain old Ebenezer Jones!" He laughed and slapped me on the back. "just plain old Ebenezer Jones. What do you know about that? Isn't it awful?" And he went off into a peal of laughter, and laughed and laughed and laughed. "Hendricks," he said, "you should have seen yourself come through that door. Oh, how funny it was. You should have been a soldier; you'd be a general!"

And that is how it ended; humiliated, shamed, and doubting, laughed at and half laughing at myself, I returned to work. But I had a feeling that after all I was right, and not such a big fool as Ebenezer Jones would have me believe. And the feeling grew. It was not long before it became a conviction, and conviction brought action.