Help via Ko-Fi

INGRAHAM shifted the broad restraining belt around his waist a little with awkward hands, for the terrific deceleration of the ship made his arms seem almost too heavy to lift. Held in place before the astrogation panel, the man fought against dizziness, for at this critical time even the slightest mistake might easily dash them in ruins upon the jagged nucleus of the comet.

Radiant Comet, Ingraham had named it, for the spectroscope had shown it to be rich in radium, the universally used "starter" for all atomic disintegration processes. A tiny speck of radium activated the atomic motors of this very ship, and without radium the slender silver rods which slowly fed into the bulky power domes about them, and above and below them, were inert and useless.

Ingraham permitted himself a backward glance, to where Durphee's gross form gasped for breath.

"Be there in fifteen minutes," he said jerkily, struggling against the weight of his own diaphragm.

Durphee did not answer, except to moan, and Ingraham turned to his panel. As the image of the nucleus slowly enlarged on the teletab, crossing the graduations marked thereon, he plied the levers and dials, until their speed was well under control.

He breathed a sigh of relief and unclasped the safety belt.

Skillfully he permitted the ship to settle, until a slight jar proclaimed that they had landed.

Durphee lurched to his feet. He was a trifle taller than Ingraham's five feet ten, and thicker about the waist. Durphee looked older than his indulgence-sated forty years, and Ingraham younger than his thirty.

Ingraham was the scientist who had discovered the true nature of Radiant Comet, looping in a vast parabola around the sun, and already well on its way to the outer spaces again.

It was situated well beyond the orbit of Saturn, because of the delay in adapting an ordinary Earth-to-Moon ship for this mad adventure.

But Durphee had raised the money, in a last desperate gamble to recoup a wasted fortune.

"How much radium is there?" Durphee asked, staring out of one of the thick ports.

THE other man did not answer immediately. He also stared over the strange landscape. He saw a desolate inferno. They had landed on the side_ away from the small, brightly yellow sun, and looked upon night. But not a true night. Everywhere the rocks gave forth a light, faint and spectral, a light too weak to dim the unwinking stars. But light enough, it would seem, to allow a man to walk over the sandy plain.

"Millions of tons of radium," Ingraham said at last. "My spectroscopic analysis—"

"Millions of tons?" exclaimed Durphee in a loud voice. "What are we waiting for? Let's get going!" He made as if to turn the handwheel that locked the oblong door.

"Wait!" Ingraham commanded sharply. "Open that door, and you're a dead man. And I am, too. Put on this suit."

He opened a locker and brought out a single garment, which included a helmet and boots shod with lead. It was a typical space suit, and Durphee knew how to put it on. Ingraham got one for himself.

"Notice the fine metal mesh, almost like chain mail," Ingraham explained, "over the outside of the regular fabric. That is, you might say, a radiation screen, activated by a small oscillator in your pack, along with the respirator tank. It will protect you from the emanations, which would otherwise burn you up. You see—"

"Let's get going!" Durphee insisted. "Millions of tons—"

"Don't be a hog!" Ingraham cut in coolly. "We've only room for a couple hundred pounds of the stuff in our insulated cases. Some of the stuff is pretty thinly distributed. We have to look for the richest—say—for metallic radium, if we can find it."

"All right, come!" Durphee begged. He slipped on the helmet, sliding up the sealing wedge. His eyes glittered greedily back of the vitrine face-plate.

Ingraham slipped on his own helmet.

"All in good time," he said levelly, speaking into the inductance phone.

"This atmosphere is mostly helium, given off by the disintegration of the radium. Sure that your respirator is working?"

They opened the lock, and the door flung outward from the pressure of the air within, and their suits instantly inflated, standing out firmly. Valving off a little air they stepped out upon the surface of the Radiant Comet. They carried their tools and instruments, and a cylindrical container for the radium.

Although the possibility of meeting hostile inhabitants was remote, they carried at their belts light little deionizer tubes, those deadly modem weapons that destroy life by inducing a chemical change within the body.

"Look back once in a while," Ingraham cautioned. "Keep an eye on the ship. We don't want to be marooned here on a comet."

"Let's start picking the stuff up," Durphee proposed, staring about him.

"Richer ahead, where those rocks crop out."

They arrived at the designated place after a long walk, and here the levelness of the sands was broken by a mad confusion of splintered rock, huge upended masses, and giant crystalline forms. It was a scene of malefic fairyland, lighted by radiance that streamed silently out from every side. Overhead was the foggy luminescence of the comet's tail, stretching out into infinity, but it was cold and unreal compared to the living light that came from the rocks.

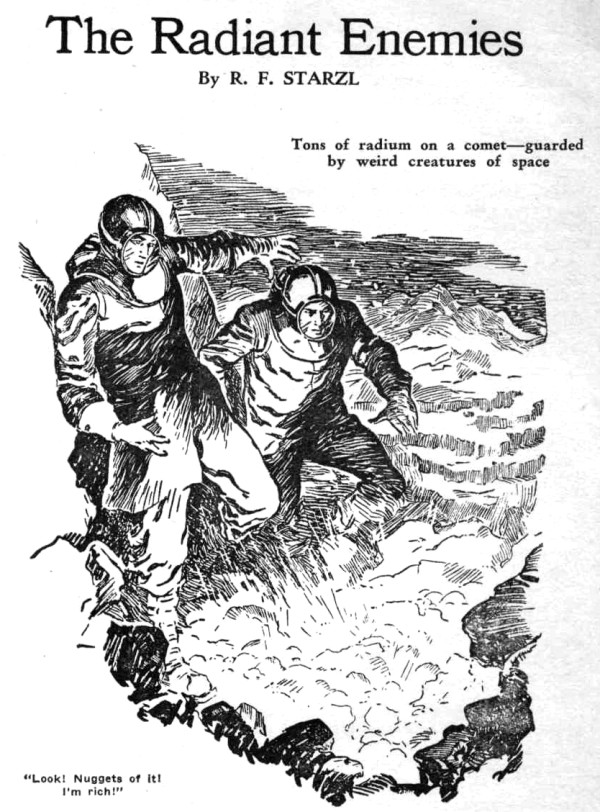

Durphee gave a hoarse cry.

"Look! Look! Veins of it! Nuggets! I'm rich! I'm rich!"

"Not till we get it back to earth!" Ingraham reminded him.

Durphee fell to his knees and snatched up fragments of the dangerous heavy metal, fondling it, holding it to the faceplate of his helmet.

"Don't do that, you fool!" Ingraham said. "Do you want to go blind or crazy? Drop it into the canister. We're going to fill that, and leave as fast as we can."

BOTH fell to work, filling the can with their incredible hoard, Durphee almost tearful at the thought of leaving so much of it, Ingraham sharply reminding him that no man could use so much wealth.

They nearly had enough when overhead appeared a light. At first it might have been merely another star, but soon it resolved itself as some object that was rapidly approaching them. Other lights appeared, fast growing.

In a few minutes the Earthmen were gazing up at the strangely beautiful beings slowly circling about them at a distance of a few feet from their heads. One may imagine a multiplicity of diaphanous ruffles, like crumpled cellophane, all aglow with prismatic light of their own.

They were not wings, those thin, radiant processes, and yet they might have served as fourth-dimensional models of butterflies. They did not move at all, and appeared to have no part in sustaining themselves in the air. They might have been merely large absorption surfaces, to absorb and hold the radiant energy pulsating everywhere on that comet.

A fittingly strange form of life in strange surroundings, thought Ingraham, looking at them wonderingly, and with appreciation of their beauty. Looking through them, he saw no body, no nucleus; merely thin, shimmering, membranous matter.

"Hey, listen!" came Durphee's sharp voice in the receiver. "Are those things dangerous?"

"They don't seem to be unfriendly."

"Well, I don't like the looks of them!"

Suddenly one of the radiant beings ceased its movements, hung, as it were, helplessly. In its shimmering membranes a hole had appeared, a hole through which the cold stars showed. Quickly, like a fire eating through cloth, the hole widened, spread through the complex ramifications of its being. It reached the tips of the ruffles, and went out. The prismatic light disappeared.

"You fool!" Ingraham tried to knock the deionizer from Durphee's hand, but the heavy space suit hindered him, and another of the radiant creatures died. And yet another, before Ingraham wrenched the tube from the other's grasp. Like glowing bubbles before a gale, the visitors swept upward and away, and in a few seconds there was no sign of them.

"What's the matter with you?" Durphee growled, stooping and resuming his excited mining operations.

"Those beautiful things; why kill them?"

"They're no good."

"As I may have mentioned before, Durphee, you're a hog. Men like you blasted the ancient Moon dwellings, out of pure cussedness. If you didn't care what you destroyed, you might have considered that it's dangerous to antagonize them—"

"Get busy with this stuff," Durphee snapped crossly. "As for them, we're well rid of 'em."

"Don't be too sure. I think they're coming back."

They were coming back. Sweeping up on a long arc from some place a mile or two across the plain, they were sweeping back like avenging fireflies, hundreds of them.

"Now we're in for it," Ingraham said angrily, handing Durphee his delonizer. "Wait till they attack."

"Will they attack?" Durphee asked, with growing anxiety.

"They've got plenty of reason to," Ingraham reminded him. "Stand still."

THE radiant beings flung themselves upon the Earthmen in a frenzy of movement. It seemed that they must be annihilated beneath the weight of that attack. But when it was over, and they recoiled, the puzzled men realized that they had hardly felt as much as a touch. The radiants hovered about uncertainly, as if undecided, and made no further hostile move.

"Thank goodness!" Ingraham exclaimed. "We're immune to their offense, It's some form of radiant discharge, and our suits protected us. See, they're sluggish now. It may take them some time to regenerate enough energy to attack us again."

The colors of the diaphanous multiple ruffles were in fact dim, lacking the living fire they had owned before.

"You mean they can't hurt us?" asked Durphee with returning courage.

"It seems not."

"Then let 'em have it!"

This time the weakened Radiants winked out in death almost instantly before Durphee's deionizer, and the survivors fled precipitately.

"You murdering fool!" Ingraham raged, grabbing for the tube.

"No, you don't!" Durphee replied, backing away warily. "Not with me owning half of a few billion dollars' worth of radium. I'm taking no chances."

"Keep it, then!" Ingraham yielded with disgust. "When there's plenty for both of us, why should I rob you?"

They fell to work, and in a few minutes the canister was full. Despite the slight gravity on that comet, it was all the two of them could do to carry their treasure. When they arrived at the ship they were both weary.

Once inside they prepared to lock the door and leave at once, for the comet was steadily carrying them away from the Earth. With a word of warning to Durphee about handling radium unprotected, Ingraham started to lock up and set the air machine to working. Suddenly he gave a cry:

"They've stolen our fuel rods!"

Through the plate of Durphee's helmet his face was ashen as he looked up. The slender silver rods were indeed missing.

"It's them unholy what-you-call-'ems!" he gritted. "The thieving—" He wallowed in foul language.

"Keep your suit on!" Ingraham warned him briskly. "We've got to find those bars or we're marooned here forever. We'll die here, you understand?"

He added, not without bitterness: "It seems those things are intelligent. If you hadn't been so quick to murder them, they might have been friendly to us. I think they were friendly at first."

Durphee tottered to the door.

"Wait!" Ingraham called. "I think I know where they come from. They may have taken the rods there."

The low cliffs stretched like the frozen surf of a phosphorescent sea across the plain. Somewhere along that low line must be the dwelling of the Radiants. Ingraham looked back once, regretfully, at the ship. There was no way of locking it from the outside, for the builders had anticipated the danger of being locked out by oversight. Now this precaution stood them in ill stead, but they must risk the chance of having the ship tampered with again.

The cliffs were nearer than they seemed. After a walk of about two miles the Earthmen arrived and skirted along their base until they came to an opening in the rock. The interior was illuminated with the same milky-white light, and Ingraham went in.

"Follow me," he instructed Durphee, "and don't use the tube unless you have to."

They passed through a corridor for several hundred feet, and, traveling downward, came to a lofty chamber three or four hundred feet in diameter. Until then they had seen none of the Radiants, but now, as if by signal, thousands of them appeared, floating in the air over their heads. Durphee pointed the deionizer at them defensively, but did not discharge the weapon, and the Radiants hovered, apparently waiting for something.

Ingraham called excitedly:

"Look, Durphee! In the center of the room! See, on that round thing?"

A ROUND boss, like the stump of an enormous tree, but crystalline in character, was in the center of the great room. Through the transparent mineral, liquid, flowing fires, in all the colors of the rainbow, could be seen, slowly ebbing and flowing, sending out streams of silent color that bathed the lofty vaults and arches like the long slow surges of a ground swell. But Ingraham was looking at the little bundle of silver rods lying on the tablelike rock—the stolen fuel bars.

Swiftly he strode toward them, Durphee following, and as the Earthmen approached the light seemed to ebb, while the Radiants retreated to the farthest extremities oi the room.

But as Ingraham extended his hand and took the silver rods, a light as dazzling as lightning and as overwhelming as a geyser burst from the boss, blinding him. Nevertheless he took the rods, and, turning, groped for Durphee.

The latter was shielding his eyes with his forearm.

"What is it? What's that light?" he asked, in alarm.

"Some powerful form of radiant energy," Ingraham replied. "I'll bet those things are wondering why we weren't killed. Our radiation screens saved us Let's get out and get back!"

The great light ebbed, and as the Earthmen turned to go the Radiants reappeared, seemingly imbued with the greatest excitement. They whirled about their beads with the fury of a tornado, and Durphee laughed.

"That for you, firebugs! Wish I had time, I'd take your god, or whatever that thing is, with me."

"Keep your tube in its clip," Ingraham warned.

"Who in the devil are you—" Durphet flared. But he got no further. A rock as big as a man's fist toppled out of some niche or cranny high overhead, struck his shoulder, ripping out a triangular rent in the mesh of the radiation screen covering his space suit. Instantly one of the Radiants flung itself on the vulnerable spot and clung there, limpet-like. A cry of desperate agony rung in Ingraham's induction phone:

"Help! It's burning me to death!"

As Durphee fell, Ingraham leaped forward and caught the Radiant in his clumsy gauntlets. He crumpled the gauzy ruffles of its being as easily as paper, and saw its shimmering light go black under his hands. Then, before another of the creatures could fasten itself on the place, he lifted back the torn flap and twisted the thin wire ends together as well as he could.

"Can you stand now?" he asked.

Durphee scrambled to his feet, cursing and groaning.

"It burned the liver out of me," he muttered.

Rocks were still raining about them, as if the Radiants had just discovered by accident this primitive method of fighting and were making the most of it.

Suddenly, Ingraham, struck on the head. fell to the ground.

He must have been unconscious only for an instant, for when he got to his knees he could see Durphee walking away, scarcely ten feet from him.

"Durphee!" he called. But his partner paid him no heed. He had already entered the corridor.

Ingraham saw that his body was literally coveted with the Radiants, but the rock had torn none of the protective screen, and he was impervious to their attack. Reeling, he rose to his feet. brushing the fragile beings from him, and so followed Durphee, raging with anger.

Too cowardly to murder him, the avaricious Durphee nevertheless was willing to abandon him to death, he thought. Durphee was running, and Ingraham ran after him. The Radiants did not follow.

JUST then Durphee turned and saw him. In that uncertain light, with the handicap of the clumsy space suits, Ingraham was not sure, but he thought he saw his partner start. Durphee spoke first:

"Close squeak!" he congratulated thickly.

"Durphee," Ingraham asked coldly, "did you see what happened to me?"

"I didn't see anything," was Durphee's sullen reply.

"You didn't see me fall, and keep going?"

"You had the fuel rods," the other man retorted. "What good would it do me to leave you?"

Ingraham felt a sense of shame.

"We're both unstrung. This unholy place! Lead on, Durphee; let's be on our way."

Their tracks in the luminous sand were clear and pointed unmistakably to the ship. In less than an hour they were close to the shiny ovoid. Durphee was the first to reach it. At the door be stopped and waited for his partner to come up.

Ingraham stepped beside him unsuspectingly. In an instant Durphee had snatched the weapon out of the clip at Ingraham's belt, and delivered a staggering blow to the solar plexus. Ingraham went down, and Durphee fell on top of him. His weight, on that small world, was not great, but the shock of the fall paralyzed Ingraham's breathing.

Something was thudding on the vitrine faceplate of his helmet; repeated blows from the heel of Durphee's hand, trying to break the glass.

Blind anger gave the under man strength, and in a fury of despair he struck back at the muffled body of his betrayer. He clamped an arm around the other's neck, only to have it painfully wrenched free. He took hold of the folds of Durphee's space suit. There was a metallic rip as the insulating screen tore away, but Durphee rolled free and staggered to his feet.

Ingraham tried to rise also, but as he did the glowing sand came up to meet him. He sprawled, and the thud of a kick in the ribs came to him only impersonally. He gave himself up for dead, and before his eyes the sand under the faceplate glowed mockingly.

But Ingraham was not dead. With faint surprise he came to that realization some time later, and immediately afterward the freezing horror of his fate bore in upon him. Marooned! Marooned on a comet and speeding away from the sun—already far beyond all past limits of human travel and drifting remorselessly into the void. Betrayed by the greed of a man to whom he had unhesitatingly entrusted his life.

He lifted his body, supporting it on his hands, and stared ahead of him, wondering if he had overestimated the passage of time, for the ship was still there, just as it had been, and the tracks in the sand showed where Durphee had stepped in, letting the door fall shut, but a narrow line showed that it had not yet been drawn tight and locked from within. The silver fuel rods were gone.

With wild hope Ingraham tottered to the ship. Had Durphee relented, or was he battening the cruel streak in him on his victim's despairing efforts?

Ingraham felt for his deionizer. It was gone, and was nowhere on the ground. He was still at Durphee's mercy, then!

After many clumsy failures he managed to insert the thick fingers of his space gloves into the crack of the door. Quickly he flung it open and stepped inside, ready to fight again for his life.

His first glance showed him that he would not have to fight Durphee. His partner lay at full length on the floor, and as Ingraham came in, ten or more Radiants rose from the prostrate body and hovered in the air, as if expectantly, projecting, one might imagine, a question.

There was no need to examine the charred fabric of Durphee's space suit where the Radiants had fastened, undeterred because the radiation screen was torn. Durphee had paid, in full.

Fear lifted from the soul of Ingraham, and shrouded it again as he saw the slender bars suspended, by some invisible force, beneath the bodies of the hovering Radiants—the silver fuel rods—the key to his escape into a normal world.

A quick glance out of the corner of his faceplate showed him that he had left the door open, and he knew beyond doubt that before he could take one step his visitors would be gone, taking the rods with them.

But even as that appalling truth sank into him, Ingraham was thinking of the prismatic beauty of these exquisite creatures, and as he did so something passed between the Earthman and the Radiants, and something like a benediction and a sense of understanding flowed from them to him. They drew together, and light streamed from one to another. The silver rods fell to the floor of the ship about Ingraham, and swiftly the radiant beings flew out of the door and were gone.