Help via Ko-Fi

THE MESSAGE FROM THE VOID

By HUBERT MAVITY

This memory of the present passes human comprehension and the Time-distortion factor spells frustration!

THE cold globe pulsed unevenly. In one comer of the great vaulted chamber a fretful generator vibrated through an ever-rising tonic sequence to still itself in the silence of ultra-sound. A dim filament flared into a point of sparkling light, and Dor Jan nodded briefly to his assistant.

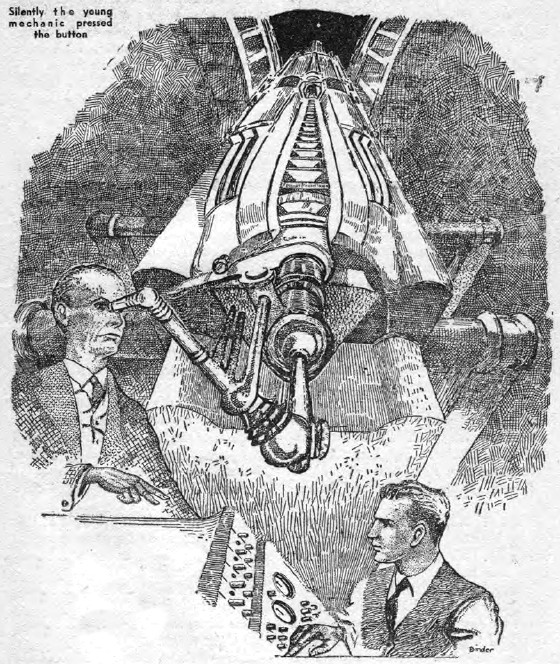

Silently the young mechanic pressed a button on the towering metal banks before him. Gears meshed. Wires, strung high above, hummed with an erratic vibration. Ozone crackled in the thin air, and a silent wave of power winged its way with the swiftness of light toward the pale green planet glowing in the darkness of the void. . . .

"Missing half your life. That's all there is to it!" declared the cheerful young man. "Nothing like a little home of your own with a plot of ground. 'Bring your friend out to dinner,' says my wife, 'we'll show him what real home life is.' Great girl, my wife. You'll like her. You say you've never been out to this section before?"

"Never," answered the other. With distaste he noted the tidy monotony of the small suburban community. Uniform stucco cottages; a thousand homes with a thousand similar tiny grass plots, a thousand cheery lights burning in a thousand windows for a thousand husbands to "come home to." His nostrils twitched with the crisping odor of a thousand chops frying on a thousand "Little Genius" gas ranges. . . .

"Yes sir, nothing like it!" boasted his host again. "Marry and settle down is what I always say. You'll see for yourself in a minute. My house is just around the corner and past—"

"—the gas station," finished the visitor.

"What? What's that?" The proud young husband stared at his guest amazedly. "Hey, I thought you'd never been here before?"

"Why, I—I haven't!" stammered the visitor weakly. "I don't know what made me say that. I've never been to Highland Corners before. But all of a sudden, somehow I felt as though I'd seen this section a long, long time ago. . . ."

IN the telescope chamber of the Flagstaff Observatory, Sir Humphrey Wimpole, R.A., shook his head as he argued with his American friend and colleague.

"No, Wallace," he said didactically, "I'm afraid we must discard your fanciful theory of life on other planets. If you'll forgive my saying so, it smacks too much of the romantic. Like those incredible yarns one reads in the science-fiction magazines. Why, the atmospheric conditions, the lack of warmth and light, the shortage of oxygen—"

"But, Sir Humphrey," insisted Professor Wallace, "you must remember this. All life need not be exactly in the same form as ours. Different bodies, adapted to strange environments. A different form of reasoning, perhaps—"

"Tut, tut!" shrugged the British scientist impatiently. "All reasoning is based on the same fundamentals. You know as well as I do that the Milan Observatory has been attempting to communicate with other planets for more than thirty years.

"Twenty-four hours a day they broadcast a series of signals based on pure mathematics—the science which all logical creatures must recognize. The Law of the Squares. Two, followed by a four. Three, followed by a nine. Then a four—with a pause.

"Surely if there were intelligent creatures, say on Mars, they would understand the fundamental principle of this squaring factor—and send us a logical solution!"

He stopped abruptly and passed a bewildered hand over his broad face. The American leaped up.

"Sir Humphrey! What's wrong? Shall I get water?"

"No—nothing, thanks," faltered the visiting astronomer. "it's nothing at all. Just a peculiar sensation, such as we all experience occasionally. For an instant I felt that I had been through this same scene once... oh, a long time ago! And this is my first visit to America. Odd, isn't it?"

The magazine editor's look of amusement faded; gave way to a disturbed frown. He stared angrily at the manuscript in his hand, and pressed the buzzer on his desk.

"Miss Jenkins," he ordered, "send Murphy in here!"

Murphy entered, the broad grin on his face fading as he glimpsed the editor's expression.

"Murphy," growled the editor, "what in blazes is the idea of sending this story up here to me for reading?"

"Why—why, it's good!" stammered the first reader. "As a matter of fact, it's the best story I ever found in the unrush mail. And from an unknown, too. It shows a world of promise!"

"Good!" snorted the editor. "Of course it's good! It ought to be. It's the rankest kind of plagiarism. A direct steal from. . . from. . . well, I don't exactly remember where I read it before. But I did. I remember reading this story a long time ago. . . ."

The reciting student swayed suddenly; raised a hand to his forehead and shook his head. When he lowered it again the color had left his face. He stared at the professor with vaguely frightened eyes.

"Herr Toggman—" he whispered.

"Yes, Wilson?" The psychologist glanced at the boy curiously.

"I'm sorry," said the student, "but I've quite forgotten what question you asked me. I just had the most confused feeling. I felt as though I were suddenly repeating something I'd done a long, long time ago. Yet this is the first time we met in this classroom!"

THE professor smiled gently.

"A very common sensation, Wilson. We will discuss it at greater length later in this course. It happens to all men at some time or other. Every psychologist recognizes it, and has some theory to explain it. Henri Bergson calls it, 'the memory of the present.'

"Humans walk in g down strange streets, talking with new acquaintances, often stop short—believing they have done the same thing some time before. Some people claim the sensation has some significance, but that is palpably absurd. It is an utterly meaningless—"

In a control room more than 50,000,000 miles distant, Dor Jan removed the amplifying unit from his head. There was defeat in his large, many-faceted eyes as he gestured to his assistant. Once more a button was pressed. The crackling hum ceased. The generator whirred and died. The light of the pallid globe flickered wearily.

"Success, master?" The robot's assistants thought came to the Martian astronomer's mind anxiously. Dor Jan grimaced.

"No. Failure again. I fear I must report to the Academy that the green planet definitely does not sustain life. I am certain that our signals reached there. Still, in more than 500 rennai of experiment we have received no answering signals from its cloudy obscurity.

"But surely. . . surely. . ." sighed the scientist, "if there were intelligent creatures, they would understand the fundamental principles of the Time-distention factor—and send us the logical solution. . . ."