Help via Ko-Fi

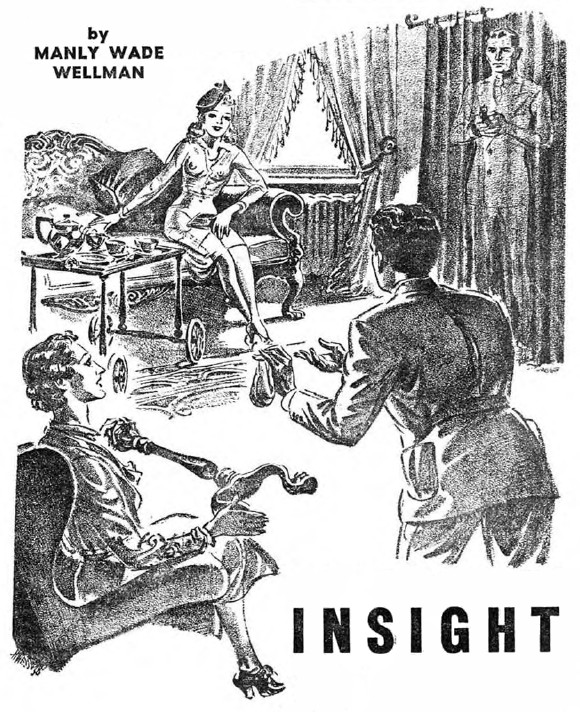

The eye-pieces, of course x-rayed not only Marjorie's clothes, but also the portiere the gangster was hiding behind.

What would you do if you had a pair of contact eye-lenses that x-rayed cloth and wood? Perhaps, like Sam Sterrett, you'd find yourself in a kidnap-gang's kill-trap—with the finger of death pointing of your sweet-heart!

I NEVER claimed to be a genius. I not even when I was a know-it-all sophomore. Of course, I got a Phi Beta Kappa key, but so does ten per cent of all Columbia graduates. Now I had finished school, I knew that key was worth only its little weight in gold. It wouldn't get me a job, and I wanted a job—and Marjorie.

Just the thought of Marjorie made me feel all moonlighty and spiritual instead of two hundred pounds and redheaded and blocky-jawed. With her in my mind, I could forget that I owed a year's tuition, and that Coach Lou Little had told me for three autumns straight that I was the most exasperating varsity tackle he'd ever failed to teach football rudiments, and that I'd have to wear a cap and gown in tomorrow's heat, and that I was only Sam Sterrett of the truck-driving Sterretts, and that Marjorie's dad—J. Barton Cannon of the Wall Street Cannons—had promised to skin me alive if I didn't leave his daughter alone. I almost forgot my invention, the one thing I had to show for four years of hard grubbing at electrophysics.

BUT I couldn't forget that, because it lay on the dressing table in my little room in John Jay Hall. Or, rather, they lay, because there were two of them. Two little bit. — of clear glass, about the shape and size of acorn cups. Not perfect, 1 knew, but a step in a new direction.

The idea—I'd better explain in the beginning—came to me in high school. I saw how glass Could modify and mix light; a prism broke it up into the spectrum, a lens focussed it to a point of heat, a mirror flashed it back at an angle, a flaw distorted it, and so on. That year, for the first time I'd read understandingly about X-rays. I began to dream, then to plan, something that would do away with all the mechanical fuss and cumber—a simple glass modifier, that would absorb instead of giving off the rays, would be a lens instead of a reflector, would, in short, achieve the transparency without use of power, artificial light or a shopful of accessories.

And now, after four years at the university, I had this to show, this pair of crystal shells that came to the problem's fringe but no closer.

I picked up one. I had made it like those little spectacle-things that fit right over the eyeball. Though almost as thin as paper, it contained five distinct layers. Between two of these was a tiny vacuum chamber, with microscopic X-ray devises—cathode, anode and anti-cathode—but made, I say, to absorb and not to produce. No induction coil, but certain metals that, fused properly in the glass, supplied power enough... never mind which metals, that's my secret. . . . I dipped the shell into a crucible of boric acid solution, then spread apart the lids of my right eye and let it snick into place there. Colorless, snug, it would be almost completely unnoticeable. Then I dipped the other shell and fitted it to my left eye.

This was my first try of the complete lenses and, though my early experiments had prepared me pretty well, I gloomed all over again. When I looked at my fingers, they were just fingers—healthy, meaty, freckled—not a shadowy rind with bones showing through, as in a real X-ray. The device was only half effective, couldn't see through living organic tissue, only thin layers of inanimate non-minerals.

Gazing at a cardboard box on the dresser, I felt a little better. Through the lid I could make out my shirt studs, my cuff links, and the medal I won for winning the discus throw. I had achieved the beginnings of success, maybe enough to build on for perfection. Meanwhile, I'd better hustle over to Riverside Drive. This was the afternoon that Marjorie had promised to slip away from her swagger college upstate and see me. That college was run like a girl's reformatory, but in the last month we'd been able to meet twice, through the help of Miss Wheatland, a new substitute instructor. She'd helped Marjorie to slip away. I thanked heaven that one teacher, at least, had a heart. So I left John Jay, still wearing my lenses; I planned to amuse the ladies by counting the coins in their purses and so on.

Heading for Grant's Tomb, where Marjorie would be waiting, I tried to figure some profit out of the gadgets. My best chance would be a sort of mind-reading stunt in a theater, and I'd never dare try—I'm not the mental type as far as looks go, and I'm prone to get stage fright, anyway. All wrapped up in thoughts like that, I took no notice of anybody or anything. I was almost run over by cars, buses, people. At last I reached the Tomb, and Marjorie came around the corner of it toward me.

Of course, I always look at Marjorie. So I looked, hard, and I was within an inch of fainting.

There she stood smiling, my dream girl, the one I yearned to marry, without a stitch on! Every curve of her, every pink inch, from her fluffy blonde pate to her manicured toes was revealed to me! And she was saying, calmly and cheerfully: "Hello, Sam, you're on time to the dot. Why, what's the matter? I declare, you're blushing!"

ABOUT that time, my poor simple one-track brain had the answer. The eye-pieces, of course, they'd X-rayed Marjorie's clothes. I hadn't thought of that, simply because I never think of more than one thing at a time. Embarrassed? The word's not one-tenth strong enough. I managed to mumble: "I was thinking, dear, how beautiful you are."

"How do you like my new dress?" she demanded, and when I said I guessed it was okay—it was only slightly visible, like a wisp of smoke—she laughed like a peal of bells. "You don't sound very convincing, Sam darling. If I hadn't mentioned it, you wouldn't even have noticed my dress at all."

By then my face was so red that I doubt if my freckles showed. I wanted desperately to get those infernal things out of my eyes, but I didn't dare, not with Marjorie looking on. She'd want to know what they were, and I'd have to tell her. Then—gee, maybe she'd never speak to me again. That was too awful to imagine.

But she didn't know, and she was saying: "Miss Wheatland helped me slip away, as usual. I'm expecting her to come along any moment—oh, here she is now. You remember Miss Wheatland, of course?"

I'd met Marjorie's teacher friend twice already. "How do you do?" I began to say, turning to greet her, and gazing into that stern, spectacled face that so belied a heart made apparently of pure gold. And then I saw the rest of Miss Wheatland, without benefit of the prim dress she usually wore, and I was worse shocked still.

For that maiden-lady face I knew was set upon the body of a man— brawny shoulders, hairy chest, a blotch of tattoo on one corded arm—and on the left side, under the muscle-ridged armpit, lurked something to scare even a football lummox with half-baked scientific ambitions.

SHE—OR HE—was carrying a huge automatic pistol, blue and shiny and lethal looking. I hadn't expected to diagnose anything like that with my X-ray!

"How do you do, Mr. Sterrett," said the voice that I recognized as Miss Wheatland's. "I hope that I find you well, young man. I'm going to take you and Marjorie to tea."

"To tea?" I repeated foolishly, as though I'd never dreamed of such a thing. I was trying to add everything up. Miss Wheatland was in reality a man, disguised as a woman teacher— that meant mystery. He was carrying a gun, a whacking big one-that meant outlawry, violence, crime. He was deeply interested in Marjorie, pretending to be her best friend—golly, that meant desperate danger to the girl I loved. . . .

"Yes, to tea," replied the casual voice of the Wheatland impersonator. "A friend of mine has given me the key to her apartment, quite near here on Riverside Drive. Come along, it's a lovely place—so restful—"

"Let's be going," chimed in Marjorie, and burrowed her little hand in under my elbow.

"Wait a moment," I began to say, then changed my mind. "All right, ladies. Let's go and have tea, by all means."

Because I realized that I couldn't back out. This Wheatland creature was after Marjorie for something. My X- ray lenses could penetrate his disguise, but not his plan. I had to tag along, protect Marjorie, foil the whole thing.

How?

We walked for several blocks, and I studied desperately every step of the way. I only half noticed that the grass was green or the sky blue, or that Marjorie was chattering happily, or that the Wheatland faker was pretending to be pleasantly philosophical, or that all the crowds of people along the Drive looked to my lenses like a nudist parade. I was full of the knowledge that I had to do something about this mess, and do it mighty quick.

THERE was a cop on one corner— a fine big Irishman, with a faint tinge of blue to the cloudy film that was his uniform, and a badge and nightstick quite plain to view. I almost yelled to him, but did not. What would I be saying? That this quiet-looking old maid was really a gunman, and that I knew because I could see through his clothes? That would settle everything, but then Marjorie would know about the X-ray glasses. And goodbye romance.

We reached the apartment building, went in and then up in an automatic elevator. Marjorie, standing close to me and all unaware that she looked to me like a very unadorned Greek statue, said: "Do you feel all right, Sam? Your eyes look glassy." I smiled and shook my humming head, but I guess my eyes would have looked glassy even without those lenses. No, they wouldn't, because without the lenses I'd never have known—oh, skip it. I'm a rotten story teller.

We rode up to the top floor, and the Wheatland bandit conducted us down a hall and into a swank apartment. The foyer alone was as big as my room at John Jay. Marjorie bounced on through and sank down on a divan in the parlor, but I paused on the inner threshold. For, at the far end of that drawing room, in a shadowy little nook, crouched a squat, burly man.

He was the greatest shock Pd had yet. He was nude to my X-ray eyes, of course, but that was no longer a novelty. He held a gun ready in his hand, but I had already spied and dared the gun under the armpit of that Wheatland hoodlum. It was his face tint made me shiver and turn cold. I know that face, as anyone must know it who ever picked up a photo paper. Bald head, heavy black brows, short upper lip, lantern jaw—it was Dillard Harpe.

Right, the one and only Dillard Harpe, for whom J. Edgar Hoover and his G-men were ransacking the country; Dillard Harpe, jailbreaker, killer, kidnapper—there I had it! The whole thing made sense on the instant. Harpe and this Wheatland yegg were out to kidnap Marjorie and hold her for ransom . . . maybe kill her. . . .

"What's the matter?" It was the mock-prim Wheatland voice in my ear. "Is there anything wrong, young man?"

"Why—why—"

"Oh, you're admiring the hanging yonder. Yes, it's a beautiful piece of Oriental silk print, isn't it?"

That was the first realization I had that the nook was hidden by a curtain of some sort, and that Dillard Harpe was ambushed behind it; or that he would be ambushed if I hadn't come equipped with those X-ray peepers. So I gulped, and managed to agree that the hanging was a perfect triumph of design. The Wheatland phoney didn't tumble, but he did put a chair for me in the corner farthest from Dillard Harpe's hiding place.

Then he touched a button on a desk, and a bell rang. In from the kitchen came an Oriental servant with a teacart. He was the ugliest Mongol I had ever seen outside of a war-scare cartoon, and the muscles of his body, revealed to my cloth-penetrating vision, looked tough and wiry and jinjitsuy. He wasn't carrying a gun, only a long wavy-edged knife, stuck under a belt of which I could make out only the iron buckle. So there were three in the kidnap gang, all armed, and I began to know a new all-time high of being scared. Three gangsters with guns and knives can put plenty of chill into one science student with X-ray lenses.

The teacups were visible, all right, and I could handle mine; but the sandwiches, being organic and lifeless, looked like a heap of thin fleecy cloud on the plate. I had to refuse with thanks. Wheatland—at last I was thinking of him as a man, not an old witch who had magically changed sex—was keeping up a conversation of fashions and bridge-playing and such woman-topics, and Marjorie, tucked up at one end of her divan, was laughing and chiming in. I didn't say much, and what I did say must have sounded hoarse and absent-minded.

PUT yourself in my place—sitting in the corner of a strange, swanky apartment, balancing a teacup on my knee; slantwise across the room, my girl, perching unconcernedly and happily, with nothing on but a shadow of gray; two men with guns, watching like hawks; and Fu Manchu's homely brother lurking in the kitchen with a skinning-knife about two feet long. It was the sort of situation that rises in a movie serial, just when the screen flashes out the words: End of Episode 8. How Will Captain Jack Tumble-water Outwit the Pirate Horde and Rescue Lady Clarissa From a Fate worse than Death? Return to this Theater Next week for Episode 9 of HOBOKEN HAMSTRINGERS. The big difference was that I couldn't wait a week for the showdown. Something was due to break loose any second, and I'd be in the thick of it.

Wheatland finished his tea, and turned to the desk. He picked up a pen and looked across at me. "Will you do a favor for us? . . ." It was still the voice of the old-maid school teacher, austere but loveable, who was bringing two young sweethearts together, and who was entitled to ask favors. I had to say, "Why, of course, Miss Wheatland," and Marjorie beamed at me for being a nice, polite boy.

"I'm going to write a little note," went on the wolf in teacher's clothing. "I was just wondering if I could impose on you to take it out and mail it." A grin at both of us, meant to look kindly. "As a matter of fact, Marjorie, my dear, this is to your father. It is to assure him that I am taking splendid care of you."

"I see," nodded Marjorie. "Thank you so much, Miss Wheatland."

"I see," was my echo, and I did see. This was to be the ransom note, and Wheatland was telling about it going to Majorie's father to explain the name J. Barton Cannon on the envelope. My mind went X-ray, too, for a moment, and I seemed to have a vision of what the letter would read like—something on this order:

Mr. Cannon:

We are holding your daughter prisoner. Don't try to find her or tell the police, if you want to see her alive again. Draw $100,000 from the bank, in old bills, and wait for word from our representative.

I let my eyes wander toward the nook where Dillard Harpe, America's Public Enemy Number 1-A, thought he was hidden from view. He was all relaxed now, standing up straight with his arms folded on his chest and the gun dangling by its trigger-guard from one forefinger. I suppose my size had given him a little start at first, but by now he had me pegged down for a dumb college jasper who, instead of being dangerous, was about to oblige by running an errand.

Wheatland had apparently finished the note and was folding it. He did something else, with a sliding motion-that would be to put the letter into an envelope. Then he lifted his hands to his mouth, licking the flap I couldn't see and stuck it down. He opened a drawer of the desk and fumbled in it.

"Here's a stamp," he announced. "Now, Mr. Sterrett, will you please mail this? There's a postbox just outside this building, on the corner.

"Of course I will, Miss Wheatland," I said, getting up and coming to the desk. "Where's the letter?"

"Why, here it is, right before your eyes." And I was able to perceive, in his outstretched hand, a pale oblong blur that must be the envelope. "What's come over you, young man? Something troubling your mind?"

FOR the first time, there was a deadly note in that voice so carefully pitched in old-maid timbre. Wheatland was suspecting me at last. It was Marjorie who saved me for the moment.

"Oh, you must forgive Sam," she laughed from the divan. "He's a science student, you know, and very serious. Probably he's turning over some new scientific formula-problem in his mind."

"Yes, yes," I made haste to agree. "That's it, a new formula."

"Indeed?" Wheatland still sounded as if he was on the point of reaching for his hidden gun. "And what, may I ask, is this new formula?"

"Oh, a—a new type of magnetic attraction," I replied on inspiration. "I was reminded by—this."

I put out my hand and picked up from the top of the desk a round, gleaming paperweight, the size of a tennis ball.

"That can't be magnetized," demurred Wheatland at once. "it's made of brass."

He knew the rudiments of science, did that disguised torpedo, but he didn't know the inspiration that had come and was now growing in my brain. Already I was six jumps ahead of that obvious objection.

"This is quite new and startling, Miss Wheatland," I babbled as plausibly as I could manage. "We've been experimenting in secret at the university. Brass can be magnetized to an amazing degree—any heavy object has, of course, certain forces of gravity to be developed and multiplied within it. Our new power, which involves the contact of living flesh, attracts masses of like substance to each other, even at considerable distance." By now I had spied, in front 'oi the arty-looking fireplace, two big brazen andirons. "Let me show you ladies one of our experiments."

Wheatland's suspicions were allayed by now, but he didn't want to see any marvels of science. He wanted me to carry that letter to the post-box, and leave him and his fellow rats alone with Marjorie. "Later, perhaps," he put me off. "Wait until you've mailed this—"

"But it will take only a few seconds," I pleaded, and Marjorie leaned forward to add, "Yes, I want to see what he's going to do."

"All right, all right," agreed Wheatland, not very graciously. "Go ahead and show us. How does it work?"

"First of all," I said, imitating the lecture-manner of my stuffiest professor, "I shall shut off the magnetic influences from this paperweight." I fished out my handkerchief and knotted the brass lump inside, then laid it on the desk once more. "Next, Miss Wheatland, I shall ask you to help me."

"Help you? How?"

"I want you to hold this." Turning to the fireplace, I picked up one of the andirons. It was wrought all over with cute modern designs, but it was big and heavy. "Let's have you sit where I was. That will give us the length of the room to show off the experiment in."

"This is exciting," squealed Marjorie. Wheatland took the andiron I forced on him, and went and sat in my chair in the far corner.

"What next?" he prompted me. "Hold your hands at opposite ends of the andiron," I directed, very impressively. "Yes, like that. Now, knead the two ends in your palms. Hard. That's it. Keep doing it."

"What's this for?" he wanted to know.

"We don't quite understand as yet," I replied glibly. "I said that this is a very recent type of experiment, and the power is rather mysterious. Some of the professors think it's the human life-force, which in some ways seems closely related to electricity, communicating itself to the brass. Others say that there is a sort of subatomic affinity between flesh and an alloy of copper and zinc—"

"Young man," interrupted Wheatland icily, as he rubbed at the chunk of metal, "I begin to suspect that you are having a rather feeble joke at my expense. Let me warn you that I am a woman who is not used to being joked with."

"Oh, but I wouldn't dream of joking with you," I made haste to say. "We're ready to start now. Keep kneading the ends of the andiron. Faster. Miss Wheatland. Now—"

I PICKED up the paperweight in the handkerchief and walked to where, in the curtained nook, stood Dillard Harpe. concealed from every eye but mine. He had come forward against his hanging, as if to peep through a hole and see what I was up to. I turned around with my back to him and faced the room. Harpe was so close to me that he could have reached out and grabbed me.

"Now." I repeated, "I shall demonstrate this new magnetic force. I shall release this bit of brass from its wrappings, and you ladies will see it float like a bubble, clear across the room. It won't stop until it touches that andiron in Miss Wheatland's lap. Are you both ready?"

"Ready," grumbled Wheatland. and "Ready," cried Marjorie. I smiled as disarmingly as I could. and held out the weight in the handkerchief, so that it dangled at arm's length in front of me.

Then I spun around, as hard and quick as I could. The brass weight swung like a blackjack. It struck the hanging, and rang like a bell-clapper on the skull just behind. Harpe gave a sort of moan and began to collapse. But I didn't wait to see him finish the fall. I let the spin carry me clear around, facing the room again. Marjorie was shrinking back on the settee, her mouth open as if she was trying to scream. Wheatland was half out of the chair, throwing the heavy andiron from his lap.

I dropped the handkerchief and paperweight, and made two striding leaps. At the end of the second, I had my head well down and my arms out. I left the ground in a flying, diving tackle.

If Coach Lou Little had been there, he'd have been critical. It's illegal—in football—to tackle with both feet off the ground. But it worked beautifully.

My right shoulder smacked just above Wheatland's knees, and back he tumbled, into the chair. The chair went over, so hard did we hit it, and broke into a dozen pieces of kindling. Wheatland struck the floor beyond, with the flat of his shoulders, and for a moment I was standing almost on my head above him. Then I twisted out of what might have been a somersault, and dropped on his belly. I remember wishing that my two hundred pounds was two thousand.

It was working out as I hadn't dare hope. He'd had to scoop that andiron out of his lap before drawing his gun, and so I'd won the moment of time I needed. Wheatland was groggy but game, thrashing around and digging for the pistol, but I kept on top and clutched his right forearm. His left fist smashed up at my face, and I felt my eyes blur as my head snapped back and those X-ray lenses flew free to land on the carpet beside us. But I hung onto his gun arm, even when he hit me a second and third time. With my left hand I tore open his blouse—now that the lenses were gone, I could see his clothing, very prim and old-maidish— and grabbed the gun myself.

I rose to my knees. Wheatland tried to grapple, but I brought down the gun-barrel across his temple. He melted down like a snow man in a heavy thaw. There was a mouthful of Oriental expletives from the kitchen and the servant rushed from there, his knife whipping out from beneath his white coat. I pointed the captured pistol.

"Drop that toad-sticker!" I yelled. "Quick!" And it tinkled on the floor. "Get your hands up and stand with your face in that corner."

He did as I told him. Now I could spare a glance for his two pals. Dillard Harpe was lying motionless, half out of sight. His head and shoulders were twisted up in the hanging he'd pulled down, and his gun had bounced well out of his reach. Wheatland lay crumpled at my feet, breathing heavily and fluttering his eyelids.

MARJORIE got up shakily from the divan. Now at least I could see that new dress of hers, about $500 worth of beautifully cut gray silk. "Sam," she was quavering, "what's happening."

"It's all happened," I reassured her. "These three merry men thought they were going to carry you off to their lair—Look out!" I warned as she came closer. "Don't step on those things, they're valuable!"

I bent quickly and snatched up the two curved pieces of glass from in front of her approaching slippers. "Thank heaven, they aren't broken," I mumbled to myself. "Not even chipped."

Marjorie was staring. "What are they, Sam?"

"Nothing," I made haste to reply. "Nothing at all, Marjorie—just a—a pair of good luck pieces. Now be a good girl and telephone the police while I hold this gun on our friends."

Ninety minutes later I was sitting in the office of the New York chief of detectives. I was smoking a big cigar that I didn't particularly want, but J. Burton Cannon had given it to me. He'd also said what I'd never hoped to hear—that he would be proud to have me as a son-in-law, and he hoped Marjorie and I would have at least eight sons just like me, and that I must be one of the brigade of vice-presidents at his bank.

The chief leaned across the desk toward me. He had to speak loudly, for in the end of the room a G-man was telephoning to Washington, trying to convince somebody he called "boss" that the Dillard Harpe gang had just been captured by a lone, college boy.

"There was a ten thousand dollar reward out for Harpe," said the chief of detectives, "and five thousand each for Wheatland and that yellow boy with the knife. Considerable potatoes, Mr. Sterrett, and I hear that you can take a banking job if you want it."

"I don't intend to," I assured him.

"I hoped you'd say that!" he crowed, and grabbed my hand. "Look here, Mr. Sterrett, we need young men like you in my department. So if you'll—"

"Thank you, sir," I said, "but I'm going to set up my own office with that reward money. I'm going to be an independent investigator."

He broke off and sank back in his chair. "I still don't see how you managed it. That gang had planned the whole snatch to the last detail. Wheatland's disguise was so good that he even fooled the other teachers; Harpe was completely hidden, and had his gun in hand; the Oriental seemed to be only a servant. Yet you found them out, captured them, and turned them over with full convicting evidence in the form of Wheatland's kidnap letter. What's your method, anyway?"

My hand crept into my side-pocket, and touched two little shells of glass. "It would be hard to explain," I hesitated.

"All I can call it is insight," nodded the chief of detectives.

"Yes, sir. Insight."

In my mind I began to plan my work. I'd keep the secret for a while, use it to detect crime and build up a reputation. I'd have a laboratory, to develop this X-ray gadget and other things. Some day, maybe when I retired, Yd tell the world. . . .

A knock sounded at the door, and a clerk stuck his head in.

"Mr. Sterrett," he called, "Mr. Cannon and his daughter want to know when you'll be ready to go to dinner with them."

Gee! How would I ever tell Marjorie about the X-ray eyes?