Help via Ko-Fi

The day was hot in the City of the Name of God. And it was dull. Juan Eapadin, who could judge a woman's virtue at one hundred varas of distance, eyed an approaching shawl-drawn figure without interest. It was that hot and that dull.

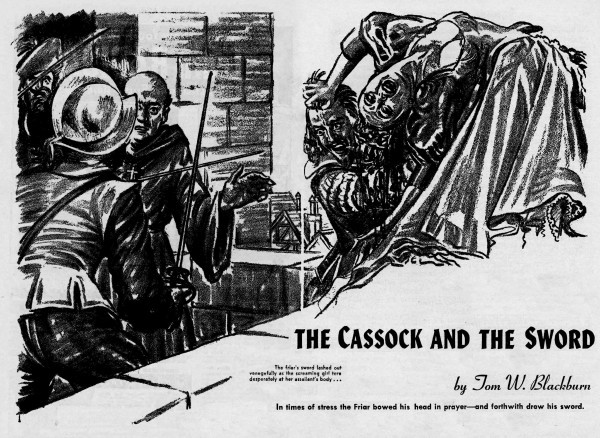

Juan Espadin was justly an unhappy man. The passage out to New Spain from the homeland had been nearly as dull as were the streets of Nombre de Dios. A man must fight dullness as he fights an enemy. In Cordoba the house of Espadin had long been noted for its skill at gaming. Guala! Who would think a man of that house could lose his modest fortune in a single shipboard game-and make an enemy, besides? Yet it was so.

Espadin grinned ruefully and shifted along the wall against which he idly leaned. The woman on the walk passed him. He no more than saw her, his eyes turned inward on his misfortune. How could a man guess that the simpering dandy he had so elegantly insulted at the captain's table was a man of note in this city? Foul luck, nothing more! It now appeared that Dario Lozan was not only a man of note, but that his family ruled this colony.

Behold, city guards had sought Espadin within an hour of his landing. Their captain was a Vicente Lozan. They brought an order banning the Cavalier Juan Espadin from Nombre by sunset. It was signed by Reinaldo Lozan, Governor. Behind the order was the threat of the old Inquisition, recently revived in this colony, and Alfredo Lozan was Chief Inquisitor of Nombre.

Por Dios. the Lozan were numerous dogs! Espadin shrugged. He must leave the city. But how? Along through the jungle swamps across the isthmus to Panama? Foolhardy he might be, but a fool—no! The beasts and brigands of that steamy dark made no distinction between the rich and honest men. It was yet three days until a train of silver mules and a company of soldiery would make the trip. Wait or stay, it was a bad matter.

Espadin shifted again. A stir drew his lagging interest up the street. The woman with the shawl—and a man. He was about to turn away. Had not the woman passed within a yard of him without casting so much as a glance at him—without raising one spark of interest in return? She must be, in fact, a hag under her veil. It was the man who interested him. An old pig. And showy. The Toledo blade at his side was too long for his arms. He was too hasty, without a swordsman's grace. And he lacked an Espadin's judgment in women.

ESPADIN started leisurely up the street. It was not his affair, but a man should not wear the gear of a cavalier without first learning the duties of a gentleman. The man had a firm grip on one of the woman's arms, halting her. He turned angrily at Juan's touch, Juan saw an arrogant face which was somehow familiar.

"Tall friend," he told the face with formality, "the lady has grown already weary of you. I tell you this to save embarrassment."

"Embarrassment!" the man protested hotly. "You misbegotten swine! Hands off, hands off! You accost me? Todos los santos! I'll read you a lesson—!"

Only the great could afford such anger over so small a matter. Espadin wondered who this spindly old follower of veiled women might be. But it was a faint curiosity. He stepped back a pace and as the man's long Toledo scraped from its scabbard, his own Cordoban steel sang in his hand. He was stiff from long weeks on shipboard. He took no chance. A man and his sword seldom look alike and a clever wrist is often in an old arm. He made a single feint and set his point a handbreath into the man's shoulder.

The fellow bleated as though struck nigh to death and sagged to his knees. Espadin caught a fistful of velvet in the crown of the man's fanciful hat and wiped his blade clean of such thin blood. He bowed then, and spoke pleasantly.

"My advice, Senor—it comes free with a pinking. Forget the lady—and get a shorter blade. It takes a stout man to make a cloth-yard of Toledo dance properly!"

Outraged, the man gave over his moaning and began to shout for assistance.

"Guardia municipal! Aqui! Aqui! Help, brigands! I am killed! Bring soldiers, bring police! Swiftly!"

A sharp blow struck the calf of Juan's leg. He wheeled. Only the woman was behind him. She had swept back her veil, exposing the face of a red-lipped. warm-eyed saint. Espadin was stunned. Por Dios, how could he have made such a mistake? A hag—ai!—perhaps in a hundred years. But beautiful, now! This old fool who thought a shoulder pink a mortal wound had showed better judgment than a Cordoban.

Ah, well, a man is entitled to one mistake. And he should be in favor. Such a beauty could feel but nausea at the old goat who had halted her. She would be grateful for a cavalier. And, perhaps, there would be reward. Bien fortuna! Even in Nombre de Dios an enterprising man might find an end to dullness.

Espadin bent low.

"Senorita—" he said, "Juan Espadin of Cordoba—"

The old goat left off bellowing. His eyes sharpened malevolently.

"Espadin?" he snarled. "I shall remember that name!"

At the same instant the girl's thick skirts rustled and a sharply shod little foot struck Juan's leg again solidly. And she loosed a torrent of bitter abuse.

"Fool! Pig! You and your hasty sword! Before God, I hate cavaliers! For three days I have baited my trap. Then, when my game at last is in hand, you spit him! You, then, can answer to Brother Paco when he asks where is this worst of the Lozans—the carrion I promised to bring him!"

Espadin saw soldiery at the lower end of the street, all too plainly in haste. He stood motionless, appalled at the continuing flavor of his luck.

"This—" he choked, "—this is also a Lozan?"

The girl nodded. Then she saw the guards. Wrapping her skirts close, she ran. Another company of soldiers appeared at the upper end of the street, cutting off escape. The girl ignored them, running lightly and with the purposefulness of one who knows where she goes. Espadin looked at the two companies of city guardsmen—doubt-less numbering among them still more of the innumerable clan which seemed to flush like rats from the stones of Nombre. He felt a tightness in him.

Pues, he was a clever fellow! He had insulted one of a family. He had ignored the orders of another. And he had pinked a third to make certain of their affection. All for the whiling of a dull afternoon and a girl!

Juan Espadin was not a man to run after a woman. The dignity of a cavalier set certain limits in such matters. But the guards were close. He overtook the girl as she dodged into the doorway of a large house which backed up to the outer wall of the city.

CHAPTER II

Jungle Friar

THE house was empty, apparently long deserted. The girl raced through dusty rooms to a door set in the rear wall of the last. The planking was old. It stuck under her hand. The guardia sounded close in the street. Espadin hit the door, drove it open, and wheeled with drawn sword to face the guards should they break into the room before the girl had a fair start. But she pulled insistently at his arm.

"This way will be useless to the brotherhood, now!" she panted. "It will be watched, thanks to the alarm you raised. But we're safe from here on. Come—!"

Espadin obeyed. The door let into a tunnel under the city wall. The tunnel ended in a thicket. The girl found a trail with the ease of familiarity. The smell of the city faded with the sunlight. In its place was the damp aroma of growing things and the perpetual twilight of rank, tree shaded undergrowth. The swamp—the jungle!

Espadin was uneasy. He was a man to see things as they" were. He knew what kind of government was set up by most of the favored nobles sent out by the King to rule his colonial lands. There were Indians in this jungle who would admire a fine Spanish head like his own as a token of revenge for many injustices. And there were brigands who would count a knife-stroke fair exchange for the privilege of feeling of his pockets.

The girl ran untroubled through the gloom. She ran lightly and steadily. Espadin was vain of his body. He gave it certain care and it served him exceedingly well. Yet he was drenched with sweat and his lungs were heaving when the girl at last stopped in a broken clearing.

She gave him a glance yet tinged with bitterness and whistled—a shrill sound from such soft lips. The whistle echoed and the clearing was suddenly full of men. Some were Indians, sullen faced and shadowy. More were brigands. The rest were the poor which crowd the streets of any colonial city-victims of swindle and false hopes and rapacious taxation. They were a strange crowd but the strangest was a round, ruddy-faced man with a bushy fringe of gray hair around a red and shining pate. He wore the robe of a holy order, but he looked like a teacher from the College of King's Wrestlers at Cadiz. His stocky body was as solid as the walls of Nombre.

The face was that of a man Espadin could savor, with the color of a bottle of claret and the genial humor of Malaga from a cask. Little round eyes winked measurement and the robed man turned to the girl.

"Not Reinaldo, not Alfredo, not Vicente, not Dario—nay, nor any of the rest. This is no Lozan! Pepita, you have disappointed us!"

The girl nodded grimly.

"Ai!" she spat. "And ask this one why! He is yours, Paco. He owns a swift blade. Where is Father Montesanto? I must talk with him."

Brother Paco tipped his head toward a great tree beyond the clearing.

"In the chapel, still. Nor has he eaten. Give him food, Pepita. Make him eat. Then, if he would corne out among the men again—they lose heart and need his voice-—"

The girl shrugged weary assent and moved away. Brother Paco called after her.

"Pepita—you had word from your father?"

The girl's voice floated back heavily.

"Does a man speak from the Inquisition with Lozans in the church?"

BROTHER PACO frowned darkly. Suddenly he wheeled back to Espadin.

"Friend, your catechism! I instruct you. When Reinaldo Lozan became governor of Nombre, he wrought many changes. Father Montesanto, bishop of the city, was driven out to make room for a friend of the Lozan who also wore the cloth. Felipe de Ardenas, commander of the old guards, was brought before the governor and ordered to levy taxes for the Lozan as well as the King. He was also ordered to pass the keys and hiding place of the old city's treasury to the Lozan. These things he refused. He was then sent to the Chambers of Inquisition, unused in Father Montesanto's time, but bloody enough since.

"Remember these things well. None here forget them. You have been brought to us by Felipe's daughter, Rosalia de Ardenas, whom we call Pepita. Those who hate the Lozans have gathered here. Those who have suffered find shelter with us. We are a brotherhood, united under Father Montesanto for—ah—prayer and self-preservation. You would join us?"

The man's ruddy face was beaded with sweat when he was finished. Juan saw here was a man unaccustomed to much talk and the use of fine phrases. Slowly Juan swept the circle of faces about him. Among other duties, such as preserving his life and health, Espadin had a fortune to regain. This company seemed barren ground. He had need of acquaintance with rank and wealth, the company of silks and velvet, if he was to fare well in this land. The dark of this swamp depressed him.

"I travel toward Panama," he said. "I am delayed only until I can reach a mule-train on the highway."

Brother Paco shook his head grimly.

"Only members of the brotherhood may stay one night in our haven. Will join?"

Espadin shrugged. Pues, why not? There was, after all, the girl Pepita. How could even these jackals be oppressive when she was at hand? Brother Paco asked his name. He gave it. Brother Paco grinned disarmingly.

"Pepita has said you own a swift sword. We will see to that. But first a man of God must see to the temper of his flock. Art a hasty man, Juan Espadin?"

Espadin had no time for answer. The flat of a thick hand rapped smartly against his cheek. He was stunned for an instant. Anger shook him. He stepped back, intending to repay the holy brother's caress with a like one from the ?at of his rapier. Brother Paco moved swiftly. His cassock was swept back over steel belted under it and a good blade winked and rang against Espadin's own weapon.

"Oho!" Brother Paco exulted. "Art quick with the steel. Juanito! Pepita told us true. But art good with it? That is a thing to know—"

Espadin lunged. He met a wrist of iron. He feinted and was held. Brother Paco thrust. Espadin gave, reversed, and layed open a rent in the man's cassock. It settled to something magnificent. The squat man was a magician. Grandee or rake, man of honor or vagabond, Juan Espadin had never met this burly one's equal. The skill of a dozen generations of swordsmen born flickered wickedly in Juan Espadin's Cordoban blade. This jungle friar met it fair.

Espadin's arm grew heavy. The man in the cassock seemed lighter on his feet, more wicked in his thrusting. Then, suddenly, it came. An old trick, learned from a grandfather. Brother Paco's blade slipped from his hand. He tripped and fell. Juan leaped forward and bent with his point at a corded throat.

Brother Paco looked up at him. But without fear. Little eyes danced with admiring pleasure and he laughed.

"Aho! Aha! Por Dios—he'd spit Paco like a pig! Pepita! Where is the little ?ower? Pepita, come here! This one will do. How he will dol Before long we have fun in N ombre de Dios— I promise you it!"

CHAPTER III

For Fortune

AT THE supper fires Pepita reappeared with a thin, white faced old man. Had he been without his robes of office, Espadin would have known Father Montesanto. The man made Espadin uncomfortable, there was that much of goodness about him. Pepita, gentlest of this company, was near to being a witch for the bitterness in her. And Paco—ai!—even a saint does not learn such mastery of living steel without consorting with the devil in the learning of it. Among the round hundred other faces about the fires were many wolves and few sheep. Violence and unrequited wrongs burned close to the surface of them all.

Yet, when the good bishop came among them, harsh tongues were silent and rough hands turned gentle. Assuredly he was a man beloved.

The father had barely seated himself when his eyes fell upon Espadin.

"I see a new face tonight, my daughter," he said. Pepita bent forward and spoke quietly in his ear. The old man nodded and his voice was touched with gentle reproof when he spoke again.

"These are times to try us all, my son," he said. "We built the King a city and he has used our labor to reward men of evil. But violence will not counter violence and a sword may not save a man's soul. Give yourself to the keeping of our brother, Paco. He will instruct you in our ways and the meat of our prayers—"

When the fires began to die and most of the banished citizenry of Nombre turned to pallets in the brush, Espadin grew restless. His belly was full but his pockets empty. He circled the clearing and came to the huge tree under which an altar had been raised. The good father's chapel. He eyed it wondering what manner of men these people of Nombre were who looked to a feeble old man for revenge and turned their hands to chapel building when the one road to salvation must lie in blood and ringing steel through the streets of the city from which they had been driven.

"Why do we hide here when the road is plain?" he asked.

Pepita raised one shoulder listlessly.

"Consult with Paco—"

It was a flat enough rebuff. But it seemed there was a flash of kindness in the deep eyes, the barest reflection of his own ready ardor. It gave him heart.

"Paco—guala!—a great one with a sword, I don't deny. But lacking in charm. I come to you—"

"I have seen as much," she answered quietly. "Art a cavalier, Juan Espadin, a figure of a man and a fine gay devil. I'll not say you no to that. But it is as nothing with me. How can water come from a dry well? My heart is dead!"

Juan snorted in half anger.

"The warm blood of Castile cannot thin so much in ten generations in these sun-blasted seas, let alone one! The heart of a woman of Spain dead because jackals burrow in a heap of stones like the town at our backs? You only think it! But I match the thought. I'll trade the head of a cursed Lozan for every kiss!"

The girl suddenly ceased to be Pepita. She was again Rosalia de Ardenas. Her proud eyes ?ashed sombre fire and Espadin saw deep into her grief.

"I will trade with any man who will bring me my father—out of the Inquisition of the Lozans!"

SHE was gone, then, and Juan stared moodily at the night. A man was a fool to bargain with a woman. He was bested at the start. To bring a man from the chambers of the Inquisition was no fair trade. What woman could be worth the risk? Yet his mind fell to thinking of some artifice by which it might be done and he was powerless to halt the thought.

A moment later a hand touched his arm and Paco spoke softly beside him.

"Find another woman and talk with her. That Paco will not hear. But with Pepita I am always close. It is a thing you should know, Jaunito!"

It was a real enough warning. Such devotion to the fair was unseemly in a man of holy office. And an Espadin was not one to brook interference in affairs of heart.

"Art a lusty man for a friar!" Jaun said savagely.

Paco looked hurt.

"Juanito, I have thought we should soon have a talk," he said sadly. "Remember that I tell you things only Pepita knows. First, I am in truth no friar. When the Lozans first arrived at Nombre, my business did well, for it was one which thrived on disorder."

Juan smiled thinly.

"A cutthroat and a picker of pockets." he guessed shrewdly. Paco spread his hands deprecatingly. But he grinned.

"Say better—a modest thief," he suggested. "However, I touched the wrong purse. The Lozans set a price on my head. I was cornered, but one of their frocked jailers for the Inquisition was at hand. He suffered accident. I took his robe. Fleeing as a friar and hotly pressed, I passed the house of Felipe de Ardenas. I thought the house empty, but a girl beckoned from its door. I followed and she showed me a way through the city wall into the jungle. Here in the swamp I would have bargained for a change of clothing. But Father Montesanto saw me too soon.

"God witness it. you should have seen his joy that another man of the cloth had joined him! He did not even ask me my order. He needed help. Pepita, to whom my life was owing, begged I give it. What could a man do? Thus Paco became a man of faith! Since, while the good father talks most earnestly with El Senor Dios, Pepita and myself make certain small forays on Nombre which feed our hatred and the bellies of the good father's flock at the same time. But Nombre is still in the hands of that cursed family. They sack it as no Englishman has yet dared to do. And we strike no real blow in return!"

Paco wiped at his broad red forehead with the wide sleeve of his cassock.

"I tell to you I am sick on it! Do I look like a man whose legs are cut for skirts? No! And this cursed robe scratches like a bed of husks! A cassock over good steel—I tell you there must be an end! Why not tonight? We are men of a kidney. We go to Nombre, eh? Two blades, honed for Lozan guards. We go behind the walls of the cathedral. We slit the throats of scoundrels hiding in robes not even so honest as mine. And we bring Pepita her father back. A man could sleep better then, eh?"

JUAN scowled. Paco made it live in words—a fit foray for two bright swords. But where was the profit? Assuredly, Pepita had offered an exchange for her father. And a man could find much joy in the face of a grateful woman. But beauty would not feed a man nor found a fortune.

Paco's eyes narrowed. His face was still genial but his eyes turned sly.

"Ye'll not go, Juanito?" he asked in mock astonishment. "Not even for a treasure locked in Nombre?"

This ill-assorted friar had mentioned treasure before. The treasury of the old city, the hiding place of which Felipe de Ardenas would not reveal, even before torture. Perhaps the former captain of the guards now had enough of torture. Having been offered a trade by the daughter, it was possible a shrewd man might make another with the father. The treasure of old Nombre would handsomely replace the modest funds with which Juan had parted on shipboard. It was the curse of the Espadins to be hasty in all things—even with 'no' for an answer. A man should consider things well. Juan shrugged.

"You have a plan?"

Paco's grin gave way to hearty, open laughter.

"Ai! Juanito, Juanito, art as much a dog as Paco!" he roared. "Ye sport silk and sweet smells and a jewel in the hilt of your steel, but ye'd be no different man in the rags of a brigand! A plan? Seguro! The Inquisition lies in an old building back of the cathedral. It is dark of the moon and guards will not be many, I think. Then, there is my robe. However far it takes us, we will go as friar and friend. After that—quick steel, hard thrusting, and swift retreat. When we have Felipe de Ardenas out of that cursed prison, we talk to him of golden bars. You see it so?"

Juan nodded, not without uneasiness. It was not the nature of a Cordoban to take another's planning for a risky night's work. But this could not be otherwise. Paco knew Nombre.

ESPADIN followed the friar through a gate into a courtyard back of the great buttresses which shored up the rear wall of the Catedral de Nombre de Dios. A dark, walled yard, closed at its lower end by a darker building. Here was the Inquisition. Built in the days when madmen were masters of the colonial church, and for the express purpose of converting unbelievers by all the implements of torture known to savage man, the evil of the practice yet clung to the building. Here was proof of the bloody tyranny of the Lozans—the ancient building reopened and its forget-ten tortures put to their own use!

Paco nudged his arm.

"Walk softly, Juanita!" he whispered. "The bones of a thousand heretics lie beneath these stones. I've no relish for adding ours to the lot!"

Juan nodded. Half across the court a man in priest's robing rose from a cluster of stone seats.

"Pax Vabiscum!" Paco offered aloud.

"Pax Vabiscum!" The man in the robe replied. And he moved on toward the courtyard gate. Paco whispered with glee.

"Fortunate I am a learned man!" he boasted. "Were it not for that Latin yon black imposter might have raised an alarm. I must learn more of the magic tongue when we return to the swamp—and Father Montesanto!"

The language of a dead race seemed a flimsy defense, especially when the rescue of another and a chance at fortune lay in the balance. But Juan made no protest. The robed man—priest or masquerading whelp of the Lozans, whichever he might be—appeared satisfied. There was but now to make an entry into the building ahead, silence such guards as might be within, and escape with Felipe de Ardenas. The sheen of smelted gold was already lighting Espadin's eyes when a bellow set up at the gate of the courtyard. The man in the robe!

"Hola—turn out—turn out! Dogs in the yard—brigands—theives! Turn out!"

"Magic tongue!" Juan spat. "You charmed him with your learning, for a fact. He was a guard. The gate is closed behind us. Quick, Paco—back-to-back with me. A dozen kirtled swine cannot down a pair of good blades standing in that fashion!"

Espadin expected sound from his companion—a laugh or a stout curse which would ring well here in the darkness. But there was nothing. He wheeled to see Paco clawing himself with amazing agility up the rough stone surface of one of the cathedral buttresses. Even as Juan watched the man made a prodigious leap from the buttress to the adjoining courtyard wall. Paco was a dark blob there for a moment. Then he was gone—outside—to safety.

Juan Espadin, who had a store of such for like occasions, swore an oath which rang like steel against the walls of the yard. A door in the building ahead flung open. Men tumbled out. One carried a torch. The rest bore pikes. They were death's heads, sheathed in long black gowns and wearing sack-like hoods with pierced eye-holes. Minions of hell would look like these. From the building they quitted came the dank odor of bloody sweat and agony. These were the iron hands by which the Lozans ruled a colony for their king. A man could run from such and count himself no coward.

And Espadin ran. He flung himself against the buttress Paco had scaled. Perhaps it was anger at Paco's desertion—perhaps that the long scabbard of rapier fouled his legs. But as the hooded devils of the Inquisition reached the base of the buttress, old stone crumbled in Juan's hands and he fell. He struck heavily and fought to his knees. There, just as his hand locked to the hilt of his sword, the haft of a pike caught him. The solid pole of wood rang brazen thunder in his head and night vanished into a deeper blackness.

CHAPTER IV

Cavalier and Soldier

IN TIME Espadin had an impression of a thin, cruel-faced youngster standing over him and a kick in the ribs which was more than an impression. The face belonged to that Dario Lozan whose nimble-fingered trickery at cards had shorn Juan of his moneys and whom he had castigated with insult in return. Espadin comforted himself that it was but a dream, a part of the haze in which a stunned man lies.

But it was not so. His head ached abominably. Could an unconscious man feel pain? He forced vision into focus. He was in a damp stone room with a low ceiling. A flambeau was thrust into a sconce on the wall. Smoky torchlight flung unsteady shadows of strange and bloody machines against the wall. Eye-bolts studded the mossy stone, dangling manacles and fetters. In one place was an erect scarecrow of a man who still clung to pride although his limbs were bent and knotted from stretching on the rack.

There was strength and a bravery in the pain-scarred face which sickened a man with pity. Espadin turned his face from his fellow prisoner just as another kick crashed against his own chest. He coughed with agony. Dario Lozan laughed.

"Art a bravo now. Espadin, he mocked. "Soon you'll be neither so glib with insult to the favorite nephew of His Excellency, Governor of Nombre. And, when you've had a brace of days on the rack, you'll be no more than a fair sword match for the old chaser of mantillas whose shoulder you pinked today. Ai! I'll have my payment and my second uncle, Alfredo, will have his for his wound!

"But most—and I tell you this out of kindness—you will pay dearest for your boldness. Noble families are few here and the Lozan noblest of these. What if the swine of the streets and the jackals of the swamps believed they also could attack us? We must guard ourselves against rabble dogs. So you shall pay—lest you seem an example to follow!"

Young Lozan wrinkled his nose at the stench of the dungeon. He produced an elegant snuffbox. Juan caught a drift of scent. It was not even a good man's nose-dust but some fancy perfumed stuff. Lozan drew an affected breath of pleasure in his vice.

"Think of these things, Cordoban," he suggested thinly. "We give you a little time—to dawn, it may be. And you think in good company. Yonder is Felipe de Ardenas, who loves street beggars better than the honor and the gold of the governor's favor. If you think I jest, ask him!"

Dario shut his snuffbox with a snap of the lid and went out. The hooded devils who had come with him left also, taking the flambeau with them. There was a deep silence in which Espadin felt the throb of his hurts and fed his anger with explosive fuel. Then the shackled figure across the black room spoke defiantly.

"Wasted!" Felipe de Ardenas said. "All wasted. Your masters think that if they give me a companion in my misery, I'll cry out to him on what I've been silent to them. Ha! A cunning trick, even for a Lozan. But a failure. The only ears to whom I'd trust old Nombre's secrets have been driven from their city!"

"Art hasty, Senor," Juan protested. "Let me but lay my hands one time only on a snuffing Lozan and you shall see one man in Nombre of whom they are not master!"

Old Felipe laughed unsteadily.

"Art but a dog at the heels of the new governor," he insisted. "Have done with your trial at winning me to you in this Satan's dark. Give me peace for my suffering and have done!"

A sob shook the old captain's voice. Even in this Juan felt the ring of steel which made a strong thing of Pepita's slender body and set her above all women in his ample memory. The blood of De Ardenas ran strongly in father and daughter alike. The old man believed he was a decoy placed by the Lozans. Juan could see no way to gain the old soldier's trust. This troubled him. There was stubborness in Espadin. He had come to this den of deviltry to rescue this man. He would not go without him. The cowardice of false friars. the sanguine torture of a colony's petty tyrants, the distrust of De Ardenas—be damned to them all. An Espadin walked no return way empty handed. There would be an answer when a man hit upon it.

Thinking thus, Espadin slept, his weary body victor over the restlessness of his mind. When he wakened it was day, a vague change from night in this pit where the Lozans used old tools to break men who brooked their will.

JUAN was barely roused when the door again opened. Two hooded guards appeared with pikes and a flambeau. With them were two more, hooded also, but stripped to the waist in earnest of coming labors. Felipe de Ardenas saw these and cackled.

"The play is to be perfect, eh?" he snarled. "I am to feel pity for this one and so not guard my tongue! Fools, 'tis useless, I tell you! I'll not talk to this dog you've thrown me. Fagh! I can tell the hand of the Lozan by the stench which goes with it!"

A wry humor seized Espadin as his fetters were struck free. This father of Pepita was a hard man to convince! The guards spoke no words. Juan was stripped to his clout. Such gear as had not earlier been taken from him was added to his baldric and rapier and the finery he had purchased in Lisbon. The lot was carelessly cast in the mouldy dust of one corner. Espadin was spread-eagled and lashed on his back across the frames of a rack The wraiths of Satin who wore no tunics put themselves at the capstans which forced the frames of the rack apart. Wooden screws turned slowly, building pressure until they cried in their sockets.

When joints stretched unbearably, Juan Espadin denied their pain. He fastened his mind on the hills of his homeland, the good Malaga in village casks, the ancients and the wise of his clan who had wed his hand to Cordoban steel—and on Pepita. The salt taste of blood came in his mouth, for a man's teeth must shred flesh when he cannot cry out. But his lips remained closed.

In mid-morning Dario Lozan bent in the doorway.

"He's asked for a priest?"

"Nay!" one of the bare chested giants growled surlily. "Not a groan from him yet—and soon his ?esh tears!"

"A pity!" Lozan said carelessly. "I had hoped the priest would already be here—one of our own. What things a Cordoban dog with such a sword-arm might have to confess! Ah, well, that for later, eh? Perhaps a turn or two more. But end it there for today. A man should have time for the repenting of sins!"

In the afternoon not even Pepita or the green hills of Spain could vie with agony. Only hatred could meet the challenge. But there had to be an end to it. There is a limit to all hatreds and the trials of all flesh. A haven of darkness loomed and Espadin plunged eagerly into it.

He roused, aching and sick, to find his jailers had been carelessly certain of the ruin they had worked. They had flung him prone in the ancient filth of the floor, scorning the effort of supporting him upright long enough to snap his fetters. Juan moved heavy limbs, found them free, and felt hope. Felipe de Ardenas heard the movement. He spoke gently.

"Not for favor or gold would any man endure what I have seen you suffer this day! I have mistaken you. But I do not know your face—you are not of old Nombre—"

"No—" Juan said hoarsely, "—of Cordoba—"

He spoke slowly, then, bitterly. He told the old man of his fortunes ashore in this colony of the King. Felipe de Ardenas clucked his tongue in wonderment.

"And you would have rescued me!"

"I would still!" Juan growled.

"For gold? 'Tis the city's and not mine to give freely "

"For myself! What is gold beside thinking of Lozan's face should he discover both of his birds flown?"

De Ardenas clucked his tongue again.

"Art headstrong—but a man, Juan Espadin! Yet I warn you, find no comfort from hope in this place. None can survive this black hole!"

"Hope!" Juan spat. "Do you kill an enemy and feed revenge with hope? Santissimo! The fools have left me unfettered and my steel is in yonder corner. Had I a way to keys for your chains we should carve us a swift way to freedom or death!"

"Keys?" De Ardenas muttered. "Pues, it is not impossible-"

THE old man spoke swiftly. Juan listened, chafing and flexing mistreated limbs. Water was brought by custom after sunset. And by two guards. One possessed keys. A ready sword—a pair of swift strokes—quien sabe? The plan was made. Came then a time of waiting in which Espadin worked and further loosened outraged muscles. He paced restlessly, his rapier clutched in stiffened fingers.

The waiting ended with little warning. The two guards came briskly. Espadin, earnest of no failure, drove his weapon too deeply into the body of the man with the water crock and so lost his grip on its hilt. Startled, the other guard thrust out with the flambeau instead of the short broad-pike in his other hand.

Espadin caught the thrusting arm, broke it at the elbow with a twist of his body, and seized the flambeau. The flaming torch was a terrible weapon. The man's head shattered dolly. Espadin tore a brace of keys from him before the guard began to fall.

His manacles had cruelly chafed Felipe de Ardenas at throat, wrists, and ankles. He winced as Juan fumbled at the locks. But when the fetters fell away he retrieved a guard's broad-pike and hobbled for the door. His face was a stone mask, set in a smile of terrible joy. Juan tore his own sword free and joined his companion in the corridor outside the dungeon.

The passage slanted upward, giving through an outer door into the courtyard above. De Ardenas seized Juan's hand when they reached this door.

"If there is trouble, push for yourself, Cordoban," he urged. "If you make it free without me, tell Rosalia I have counted you friend this night. It will carry your suit far with her!"

"I ask no man's help with a woman!" Espadin growled. "Beside, a man must live before he loves. We started together. We finish the same. Por Dias y Sus Majestades del Esptana!"

"For God and the rulers of Spain!"

De Ardenas echoed. And he thrust the door open.

Espadin hoped for luck—dark and a sprint to the gate which Paco and himself had used. There was a smoky flood of torchlight instead and a company of guards in close rank under the command of Dario Lozan and his amorous uncle, that Alfredo who wore a sling over a wounded shoulder. Juan understood. Leaving him unfettered had been but another form of torture. The Lozans had known he would try escape. They had been waiting like cats at a rat hole.

"I said it, my uncle! " Dario exulted.

"The rack was not enough for cavalier or soldier either. Leaving the sword was a masterstroke. For a fact, if you buried a Cordoban's steel with his body, he would fight his way above ground though his flesh was already rotted from his bones! Will not your brother, my other uncle, order this pair quartered on the public gibbet, now?"

Alfredo Lozan grimaced.

"The death order is in my pocket—the manner of death my choice. But first, let them sing for a quick ending. It would please my ears!"

Espadin had enough of this. He lunged forward. De Ardenas charged with him. The two Lozans dodged back. Dario screamed at the soldiers. Guards surged forward. Dario yelped again, shaken with fury.

"Have done!" he ordered. "The game no longer amuses. But do not damage the heads. They go through the city tomorrow atop pikes as warning to the reckless!"

This was the end. The writing was clear. De Ardenas saw it, too. He set his back to Juan's back and braced himself to take the first of the guards with his broad-pike. Juan flexed his blade and made it sing a last song-good Spanish steel which loved the blood of tyrants. But before rapier met pike and broad-pike met lance, a terrible yell rang out.

The ranks of the guardia wavered toward the courtyard gate. Through that passage, howling like wraiths from hell, came men of the swamp. Bounding at their head, his cassock girdled high, was the false friar of Nombre— grinning and as wicked as the blade in his hand.

CHAPTER V

Corridor to Hell

ESPADIN, for all his joy at relief, saw only the brigand. Juan fought toward him. Paco threw wide his arms as though he did not know Juan was more than half a mind to run him through.

"Juanito—comrade of my heart! " he roared. "I come in time!"

"Black rascal!" Juan gritted, "— eaving me as a hale man leaves a leper! In time—fagh!—hast overmuch thin blood in they veins, Come, up blade and I'll let me some!"

Paco's eyes grew roundly alarmed.

"No—before God, no!" he protested. "Could I help a comrade were I also on the rack? Better that one go for help than that both be lost. Por Dios, would you stick a brother?"

The alarm was sincere and the hurt look so honest that Espadin could hold no ill will. He laughed. Paco laughed with him.

"Make it a good fight, amigo," he counselled. "Pepita would nor risk our company for her father alone. But she begged these wild ones to come after the pair of you. She gained Father Montesanto's agreement or I might not have returned at all! Now is the time, eh? We are here. We fight and blood runs. Why stop? Nombre is a rich enough prize for us all!"

With the ragged bulk of the robed brigand at his side, Juan Espadin turned eagerly back into the fight. So it was Pepita who had fanned the fury of these madmen—Pepita, whose heart was dead! He grinned widely.

The disciplined guardia might have stood solidly. But discipline is no weapon against the anger of an outraged people. They wedged the soldiery out through the gate into a square before the cathedral. The doors of long-shuttered houses burst open to spew forth more mild men turned savage with hope.

With pothooks and fire-tongs they fell on the rear ranks of the guards. Here was raw justice. Espadin savored this battle as he had none other. The little ones—the meek and the gentle and the long-suffering, risen now against their enemies! Juan forgot he was without means and that his sword must win him fortune. It was enough now that it drew blood.

News of the fighting spread. More men poured into the city from the swamp. Among them were Pepita and Father Montesanto. They joined with old Felipe on the steps of the cathedral. The holy man Juan had shunned in the swamp as a man too goodly for earthly life, spoke to the crowd. From the gentle lips of the old father poured a fighting man's prayer—a plea ringing with simple faith that the good God was with Nombre and that His hand guided whatever weapon struck at a Lozan.

Juan had believed that Paco and himself gave heart to the men of the city. But this was as nothing to the exhortations of Father Montesanto. In truth, Nombre loved its bishop and his God. They turned wilder still. those fighting fools. The guards fell back. trembling at collapse. Suddenly a fierce mounted company poured without warning from a side street. Two men rode at its head. One was Vicente Lozan, who had succeeded De Ardenas as captain of the guards. The other was a fat man so pompous that he could be only His Excellency, Reinaldo Lozan, Governor of Nombre.

THE wild ones bunched against this attack. Felipe de Ardenas plunged among the city men, striving with a soldier's skill to organize their forces. Riders were dragged from saddle, dismembered before they touched paving. But the charge was too savage for clumsy weapons to turn. It was done in a moment. Father Montesanto and the girl beside him on the steps were seized, flung across horses, and the troop wheeled. A brief skirmish and they were free with their prisoners. Dario Lozan, among the foot guards, flung an ultimatum.

The two were hostages to the end of fighting. All arms must be down by dawn, the crowds dispersed without further violence. Certain leaders—Felipe de Ardenas, a Cordoban vagabond called Espadin, and the notable brigand Paco—were to have surrendered at the palace by the coming of light. Failing this, the good father would be hanged in front of his people and the Ardenas wench impressed into the household of Alfredo Lozan, who had spoken for her-—

A grapeshot volley from English guns could not have more swiftly cooled the ardor of the men of Nombre. They broke, permitting the guards to fall back across the square to the facade of the governor's palace. The bubble of a great hope was near to collapse. Old Ardenas fought to save it, climbing again the steps of the cathedral.

"I am one who will not surrender!" he roared. "The girl is my own blood. The bishop is my friend. But Nombre is my city. Forward. circle the palace! They'll not dare to harm either hostage if there is no escape for them after-ward!"

Juan saw the old man's face. It was a brave gesture. But it was not enough. Nombre's warriors did press on sullenly toward the palace. But it was plain they would fight no more.

"That you knew a serving-wench in that place!" Espadin breathed to Paco. The brigand's small eyes lighted eagerly.

"A rear door, eh?" he guessed shrewdly. "No wench and no door. But I do know a passage. A risk, Juanito—and no gold at the end of it!"

"Pepita is there!" Juan snapped. "Is that not enough?"

Paco laughed as though a last barrier was gone.

"I would have spoiled the bargain she made with you, Juanito," he said. "But not now! Pues, we have been asked to surrender. We go. then, to the governor to do this, eh?"

Paco slid into a dark and narrow alleyway. He found a ledge in the darkness, travelled it many yards to a buttress by which he climbed to a higher level. There was another ledge, then a tile drain all too insecurely fastened to the towering wall. From this they reached a third foothold on which a feeling of great height and hard stone far below seized Espadin. Suddenly Paco vanished from in front of him. A moment later he found a casement open and crawled through, also. A room took vague shape. Dull metal gleamed from shelving. Juan understood Paco's knowledge of this entry to the palace. In a few moments a man without principle might load a sack with enough silver to provide a month's good living from the cannisters and state goblets stored here.

Paco pulled open a door, stepped cautiously into a long hall. Juan followed him. The far end opened into a stairwell from which short corridors led to a number of apartments on what must be the front of the third floor of the palace. A heavy, gated grill closed the head of the stairs. Four guards stood on duty at the gate. Paco nudged Espadin, pointing to the belt of one of these. Keys hung there. The meaning was clear. These guards could not be attacked without alarm. Yet should that gate be closed and locked, this floor would be cut off from the rest of the house—and reenforcements. So well protected, this floor could be none other than the haven of the Lozans. Juan nodded at his companion and freed his steel.

As they had done before, Espadin and Paco moved as one. There was a clash of steel, a curse, and one cry because Paco was clumsy—and painful-with his first thrust. Before his own second victim struck the floor, Espadin slammed the gate closed. Alarm rang on the floor below. Guards thundered up the stairs. Paco's stubby fingers fumbled with the keys. The tumbler turned but an instant before the first of the guards rammed his shoulder against the barred portal. Paco spat in the man's face, laughed, and twitched in his robe as though the rough cloth was again chafing him. The brigand then leaped into the dividing corridors and tried three doors in swift succession. Only the fourth was locked—and from the inside.

With the palace ringing alarm behind him and soldiers wildly trying to throw weapons between the steel bars of the gate, Espadin foiled his comrade and bent before this door. Thrusting his thin Cordoban blade into the casement joint, he found the bolt with its point and shot it back. The door swung wide.

CHAPTER VI

Nor for King or Gold

ESPADIN had hoped for triumph—a moment of facing four craven dogs who trembled in their slippers and showed the pimples of cold fear through the thin silk of their long and costly hose. A man looks no better to a woman than when vengeance puts enemies in his hands. But the Lozans were desperate and a coward's cunning is a terrible thing.

Alfredo, still hampered by his pinked shoulder and always stupid, sat as he must when alarm first sounded in the hall. Reinaldo, his fat no longer lending dignity, clutched a bodkin of a dress sword in the center of the room. But it was Vicente and the merciless Dario who held the prisoners. They stood beyond the open windows of the room on a balcony, beyond the railing of which the square was far below. Paco would have leaped at them. Espadin stayed him with a quick hand. Dario smiled thinly.

"Art wise, Cordoban!" he mocked. "But to stand is not enough. Your comrade has keys which belong to His Excellency. Hand them over!"

Paco looked helplessly at Espadin. It was a hard thing, but Juan nodded. There could be no doubt. Dario and Vicente would not hesitate to fling the girl and the old man into space. Paco's hand moved jerkily. Sweating, Reinaldo Lozan took the keys and waddled into the corridor toward the stairwell and the gate. Dario's smile grew wider.

He moved a little and a stirring murmur rose from beyond the balcony, proof that the sullen crowd in the square could see what happened high above them and so was watching. Dario scowled and his lips tightened.

"A hostage is useless when a trap is sprung," he said softly. "Nombre has not learned her lessons well. She needs stronger medicine than any we have given her. Put the old man over first, Vicente!"

The hand of God could not have stayed Paco then. He lunged forward like an animal. Even so, Espadin was onto the balcony ahead of him. There was but a moment. Father Montesanto. who had stood with bowed head. suddenly straightened and thrust a feeble hand bravely into Vicente Lozan's face. That gesture of defense saved the bishop of Nombre a terrible death. It stayed Vicente just long enough for Paco to reach him. Juan heard Vicente's breath choke off in a sob as stout fingers tore deep into his throat.

Rosalia de Ardenas was already swung from her feet when Espadin's crashing weight shook her from Dario's grip. Juan knew only that she fell—and within the railing. Nothing more. At too close grips to use his long blade, Espadin was put to it to fend off a poniard in Dario's grasp. And he was but scantly successful. Razor steel split his doublet from shoulder to thigh and a thin line of welling red was traced down the bunching muscle exposed under the rent cloth.

Juan had no choice. Before that needle of death could strike again, he had to be free of his enemy. Dropping his rapier, he reached with both hands and found purchase. Weight came on his arms, his shoulders, his back. A weight which rose squirming high in the air and went hurtling out from him.

A high, thin wail sounded. There was an uglier sound from the pavement far below. And a sudden, exultant roaring as those at hand recognized the crushed body which had plummeted down among them. The square, which had been nearly silent, rang again with men moving toward final battle. Father Montesanto peered over the railing of the balcony with a strange look on his face. Paco yet thrashed purposefully on the floor with Vicente Lozan. Espadin thought of the fat governor and the keys with which he was unlocking a gate to send a flood of guards into this room. He wheeled—and stood stunned.

His rapier was not where he had dropped it. Its hilt projected at a crazy side angle from the trunk of Alfredo Lozan. The man held a weapon of his own in his hand and stared down at the weapon which skewered him. To one side, ever so little to one side and close to the Lozan, Rosalia de Ardenas stood white-faced. But she did not look at Alfredo. Her eyes were on Juan Es-padin and the great fear she had felt for him was not yet gone from them. Beyond believing, Juan understood. Alfredo had come at his back. And Pepita had come between him and death!

ALFREDO took a tottering step and fell. Juan caught his blade as the man went down. A single stride carried him to the hall door to face a tall guardsman, plunging in. A parry and riposte, then Juan stepped aside. The guard fell inward and Juan dodged back to face another. The doorway was deep and of a right size for a swordsman to work one foeman at a time. The guards, shaken and uncertain, did not think of bringing up a long-shafted pike.

Another fell. And another. Blood made the planking treacherous. The fallen bodies hampered Espadin, who fought much with his feet. Then a hand reached past him, a hand with broad fingers, and hauled one carcass away. It came back for another.

Each time there came, after a little, an approving roar from the square below. Espadin puzzled at this. But he lacked time to think.

Suddenly it was over. Tumult within the palace reached the stairs and climbed to the topmost floor. Familiar faces from the swamp appeared behind the guardia in the hall. Swords clattered to the floor in surrender. Juan turned back into the room, then. No single body of the slain remained. Paco grinned, dusting his hands with pleasure. The collapse of the guards was understandable, then. How could men fight under a rain of their own dead from above?

"Juanito, my pigeon!" the swamp-friar of Nombre exulted, "—what we have done! Come. now, swiftly. I once had connections in this house. Reinaldo is still on this floor and he has keys. I will know if the fat fool lies-but he will not! The treasure of the Lozans for those who fought for it!"

Juan shook his head.

"For me only a small purse containing the value of five hundred cunas de oro in exchange for one of like size and weight I lost to Dario's shipboard cheating. The treasure of the Lozans for those who fought for it—ai!—that is just. Reinaldo and his keys are best for Father Montesanto—for the poor of Nombre!"

Paco showed liquid disappointment.

"No fortune? Then glory, Juanito! Quick, onto the balcony. Talk to the wild ones below. They have loved your good blade and we have need for a new governor!"

Juan shook his head again.

"Por Dios, must you make me over, Paco?" he protested. "Am I a graybeard to rule a city? Put Felipe de Ardenas on this balcony and let Nombre make its choice!"

Paco was near to tears.

"Art the friend of my heart, Juan-ito!" he urged. "F or the love of heaven, take some office where I may share the glory! Have been a holy man long enough. I must be rid of this irking robe or I die. Speak to the guardia. Many are loyal to Nombre. A sword makes at least a good captain!" Juan grinned.

"That much is true. Father Montesanto is my witness that your sword is not the sword of God. But what better wisdom than to make a brigand chief of civil guards?"

Scandalized hurt leaped into Paco's eyes.

"Juanito!" he cried. "Have betrayed my secret—the father heard."

Father Montesanto turned to Paco, dropping a comradely hand to his shoulder.

"I have long thought you a most unusual friar, Brother Paco," he said gently, "but even God may use strange tools. Go to your policia, take their command. And serve Nombre as well as you have served me!"

A HUGE relief broadened Paco's features. He mumbled thanks to the bishop of Nombre. He grinned at Espadin. And he rushed into the hall. Father Montesanto followed after him. Presently Juan heard the father's voice, suggesting that Felipe de Ardenas might make a fit governor. The men of Nombre answered with loud acclaim. With their bishop, they moved down the stairs in search of the proud old soldier who had loved Nombre more than life, carrying their vote and their confidence with them. The upper hall was emptied when a group of loyal guards turned also down the stairs, prodding Reinaldo Lozan along prisoner in their midst.

Thus order came simply to a city in just revolt. Espadin was alone in a room with a woman he once would have taken at a bargain and now could not. The change was a softness in him and he marvelled at it. Rosalia de Ardenas crossed the room to him and he saw her again as Pepita of the swamp—a girl without family whom he would have courted in the shadows of Father Montesanto's chapel.

"Art a strange man, Juan Espadin," she said slowly. "There is a hunger in you, for I have seen it. Yet you have turned down both bread and wine— glory and reward. You want something more than these?"

"Perhaps," Espadin agreed with tight restraint. "I want to sail a ship across to Spain. I want to take the fat pig we destroyed today to face the King who sent him to us. I want to tell the King what Nombre chose in place of a Lozan. It is time even Kings learn that here is a new land where little men are stronger than the mighty—where people will desert a wicked city for a swamp where there is freedom and honor for their God!"

"No more than this—you want no more?"

Espadin had kept his eyes averted and his thoughts on Nombre. He had been a strong man in the thin light of this dawn, refusing this woman lest only her bargain had brought her to him. But his eyes met her eyes, now. And she was still the girl of the swamp—but with a living heart. Pues, strength could rob a man of much!

The girl's shoulder stung the knife-mark on his chest and the blood of an Espadin stained her jacket. But what of this?

"I will tell the King here also is a land where the women are witches! " he murmured huskily above her lips.

"And I—I will stand behind you, Juanito, and smile in the King's face. He will think you a great liar!"

The End