Help via Ko-Fi

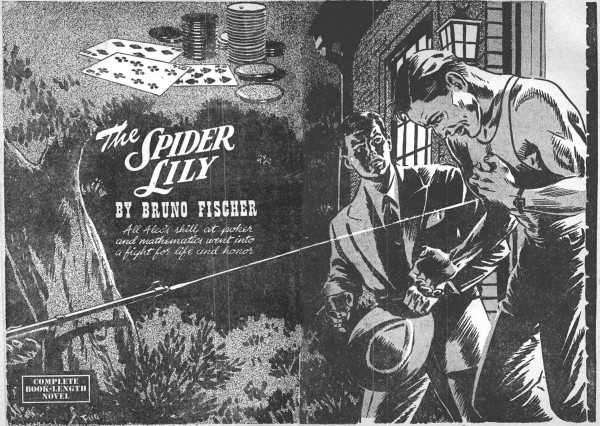

SHE wasn't there. I paused on the lowest step and looked past the two women running toward me. Lily wasn't anywhere on the narrow station platform.

"Getting off, Lieutenant?" the conductor said.

I stepped down to the platform. My sister Ursula flung her arms about me and held me to her cushiony bosom and said my name over and over as if to taste the sound of it.

Miriam watched me with a tremulous smile. Her black hair was gathered back in a tight bun, showing her high forehead to the hairline. The summer sun had given an Oriental burnish to her normally dark skin, making a charming contrast with the eggshell white of her thin, nicely filled sweater.

"Where's Lily?" I asked Ursula.

"She couldn't come." Ursula's fingers ran over the ribbons on my chest. "You didn't write us about all those medals."

"Why couldn't Lily come?" I said. Ursula stepped hack. "I'll explain later. Aren't you going to say hello to Miriam?"

I held out a hand to Miriam. She didn't seem to notice it She leaned against me and tilted her face and I brushed her mouth with mine. Her hands touched my arms and fell away quickly when I turned back to Ursula.

"Is that the way to kiss Miriam after two years, Alec?" Ursula boomed.

She was a big woman, large-boned rather than fleshy, handsome rather than pretty. She was feminine enough for most men's taste, except when she was bossy and then she assumed the voice and manner of a backslapping male. I'd never liked that in her, and it jarred me now, particularly.

"Has anything happened to Lily?" I persisted.

There was a silence overlapped by the roar of the departing train. Ursula and Miriam exchanged a glance. Then Ursula said, "She's not home today," and tucked a hand through my arm. "How about showing some interest in Miriam and me?"

"Why hasn't Lily come to the station?" I said. "I phoned yesterday from New York that I'd be on this train."

Ursula's mouth made a crooked diagonal line, the way it did when she was annoyed. She didn't have a chance to say whatever she intended to because just then Oliver Spencer came around the corner of the station house. He hurried toward me with outstretched hand.

He was a little man with a habitual stoop and a fringe of gray hair forming a halo about his bald pate. He owned the largest food market in West Amber, and he had a daughter with whom I used to neck and a. son with whom I'd gone to high school.

"Well, well!" he said, pumping my hand. "I've heard you were coming home from India. Are you better?"

"I wasn't wounded." I picked up my bag.

"I know. I heard you were very sick. Some kind of mental—"

Ursula said quickly: "Doesn't he look fine, Oliver? So ruddy and clear-eyed."

"Oh." Mr. Spencer glanced at his watch. "You look fit all right, Alec, I've got to see about a shipment of eggs which came by express." He shook my hand again and bustled off.

I WALKED between Ursula and Miriam down the length of the platform. None of us seemed to have any words. This wasn't at all the way I had expected it.

When we reached the car, Ursula paused with her hand on the doorhandle and looked back. "I should have told Oliver that I'm calling off tonight's game. Unless you'd like to take a hand at poker, Alec?"

"I expect to spend the evening with Lily, so go ahead and play," I said.

Ursula slid behind the wheel without comment. We sat three in the front seat, I in the middle. The sedan still had its luster, inside and out, but it had trouble climbing the hill from the station to the town.

I leaned forward, listening to the motor. "It needs at tune-up. I'll work on it tomorrow."

"The car missed you almost as much as we did," Ursula said.

That was all. I'd been gone twenty-two months. I had come home from the other side of the world, and conversation lagged after a couple of sentences about the car. I felt Miriam's thigh against my right thigh and Ursula's shoulder against my left shoulder, but we weren't together at all.

We drove through the business section of West Amber. It was exactly the way I had left it: the sun baking the road and men in shirtsleeves lounging in the shade of storefronts and women in slacks wheeling baby carriages and children playing box games on the sidewalk and cars searching for parking space along the curb. Month after month, lying in a sticky bunk under netting or flying six miles above earth or brooding at the tailend of drinking too much, you saw this scene in your mind and your insides contracted at the thought of coming home to it or of never coming home to it or to anything, and sometimes you were sure that you would weep like a woman when you saw it again.

Here I was and it wasn't like that. It wasn't anything but a familiar scene.

"Look," I said angrily. "When I was grounded, I wrote you that there was nothing much wrong with me, physically or mentally."

"Oi course," Ursula said.

"Then what was Mr. Spencer talking about? He seemed to expect me to get off the train cutting paper dolls."

"I suppose he heard—" she had trouble getting the rest of it out.

"That I was psychoneurotic?" I said. "So what? In the Air Forces that term covers almost anything. In my case it merely meant that the flight surgeon decided that I shouldn't fly combat any more. Most men can't fly combat to begin with. I'm at least as normal as they are."

"Of course."

"Then, damn it, don't try to shield me from myself or from anybody else!"

URSULA took her eyes from the road, but not long enough for me to look into them. "What gives you the idea that anybody is trying to shield you from anything?"

"You do. I can take it. Go ahead and tell me that my wife walked out on me."

"She didn't," Miriam said, her voice a little breathless.

"Then why wasn't Lily at the station to meet me?"

"Alec, stop screaming," Ursula said quietly.

I hadn't realized that I was. I sank back between the shoulders of the two women and found that I was panting.

"All right, I screamed," I said. "I suppose that proves that I'm a mental case."

"Nobody thinks you are," Ursula said. "Don't be so sensitive."

"I'm sorry," I said. "There's no reason why I should be sensitive. None at all. I've been away for a couple of years in a place I hated, doing what no man should be made to do. All that sustained a lot of us was the thought of getting home. Home to our wives, those who had them. Now I'm home, and my wife—"

"Alec, listen." Miriam touched my arm. "Lily—"

"She happens to be visiting relatives in New York," Ursula cut in tartly. "That's why she wasn't at the station."

"Then why didn't you let me know when I phoned you from New York? I could have met her there."

"Because we wanted to see you," Ursula said. "Lily would have kept you away from us for days. You'll have time enough for her."

That was all it was—jealousy. While I was away, they'd been kind enough to Lily whom I'd brought home to live with them; otherwise, Lily would have let me know in her far-between, carping letters. But now that I was back they resented another woman's having predominant claim to me. Females must own a man, and both of them had owned me. They were on the defensive because they had played a shabby trick on me.

I said: "Ursula, please drive me back to the station."

The car slowed down, but not enough. "Can't you wait at least a day to rush into her arms?" Ursula said grimly.

"She's my wife."

"And Miriam and I are nothing to you."

"You know that's not true. Only—" I couldn't bring myself to put it into words for them. I had a right to Lily's body and it was a beautiful body. Perhaps I hated her. I hardly knew her. There had been the letters, but before that there had been the three nights with her. I had come home for more of those nights. I had to have them.

"I haven't any idea where she is staying in New York," Ursula was saying. "You'll have to wait till she comes back or phones."

What was there to say? They had me blocked off. The car was laboring up Mandolin Hill Road.

"Here we are," Ursula sang out, abruptly cheerful.

THE CAR swung into the semi-circular driveway and pulled up in front of the porch. The two-story frame house, painted ivory and trimmed royal blue, glistened in the sinking sunlight. The hedge needed cutting and the lawn was too high—another chore to keep me busy until Lily returned. If she did return.

I reached into the back seat of the sedan for my bag and went up the porch steps with Miriam. Ursula had gone ahead to unlock the door. There was a solemn and remote set to Miriam's angular face as she moved at my side, and no words for me.

"What's wrong?" I said. "Have you been reading those sappy articles for civilians which tell you to treat returned veterans as if they hadn't been away? Neither of you asked me a thing about myself."

Miriam stopped on the top porch step. "It takes time for us to get used to you, Alec. You're so different, so much older. Especially your eyes."

"I'm psychoneurotic," I said. "A mental case. It shows through my eyes."

"Please, Alec!" Miriam took my hand. Her palm was hot and moist. "Stop twisting everything we say. Stop feeling sorry for yourself."

"That's another symptom, feeling sorry for yourself."

She yanked her hand away and strode angrily to the door. Then she turned, suddenly contrite. "Alec, remember this. Ursula and I love you more than anybody else does."

"Meaning more than Lily," I said. "What about her?"

Ursula was in the hall, looking out at us. "It's after seven, Alec, and dinner is practically ready. You'll want to wash up first."

Miriam stepped into the hall and continued on to the kitchen. She hadn't answered my question.

My room was waiting for me. When I closed the door behind me, the sense of being home came in a rush. These were the things I knew best: the walnut bed and dresser, the bookcases crammed with volumes on poker and chess and cryptography and mathematics, the stand containing thirty worn volumes of the Encyclopedia Brittanica, the portable typewriter in its case, the tiny-radio on the desk, the chess trophies on the corner shelf and the hand-carved ivory chessmen, the rifle and barbells on the wall and the two Hogarth prints.

I dropped my valise and took down my .22 repeating rifle from its pegs. It had been cleaned and oiled within the last week, probably by Ursula who knew something about guns and wasn't a bad shot. I replaced the rifle and opened the closet door. My civilian suits hung there, cleaned and pressed. In the dresser I found shirts, socks, underwear, all freshly laundered.

It was all there for me to take up where I had left off.

I shed my uniform and left it on the floor and got into the checker rayon bathrobe and went into the bathroom for a shower. I returned and dressed in light gray slacks and navy blue shirt and powder blue knitted necktie and dark gray tweed jacket. Then I walked back and forth across the room, looking at myself in the dresser mirror every time I passed it. Little by little I got used to myself.

The clothes helped most. Home to clothes which were not like everybody's. Home to my own room. Home to Ursula and Miriam. They were swell women, and Lily wasn't worth any part of them. But Lily was the woman I had come home to be with.

CHAPTER II

Yesterday and Today

THE dinette was separated from the living room by an arch and a step. When I raised my eyes from the table, I looked directly at the large framed photo of August Hennessey above the redbrick fireplace. He had been a blonde giant, half-Irish, half-Swede, enough man for a woman like Ursula. In the photo he wore a grin as wide as his broad amiable face, and a yellow curl hung rakishly over his left eye. He could have passed for a romantic adventurer out of the more lurid pages of fiction. Actually he had been a salesman of glassware.

Ursula married him when she was eighteen. I was three at the time; our mother had had her two children fifteen years apart. Ursula had been visiting an aunt in New York City, and one day she led that huge man into the house by the hand and announced that they were on the way to Mexico for their honeymoon.

They visited us about once a year, but the first definite impression I have of August Hennessey was his excitement when I beat him at chess. I was seven, and he promised me that during his next visit he would teach me the fine points of poker. That was his game, he said—something like chess in that you must anticipate your opponent.

But when August Hennessey and Ursula came next year it was to attend Ma's funeral. So there were no games, chess or cards. They wanted to take me back to live with them in the home they had built in the upstate New York town of West Amber, but Pa refused to let me go. He was a meek, taciturn trolley car conductor whom I'd never got close to, not even when I had become old enough to share his passion for chess, but now he needed me in his loneliness.

I never saw August Hennessey again. While on a selling trip to Buffalo, his car crashed into a truck and he was killed.

He left Ursula the house clear of mortgage and, like most salesmen, a substantial insurance policy. I don't know how much it was, but enough for her to live in comfort and later support Miriam and me. For years there was a rumor in West Amber that had quite an income from her Saturday night poker games, but, of course, there was no kitty for the house. Though she was very good, the men who played with her were no slouches, and I doubt if she won much more than she lost.

Ursula wasn't one to brood in an empty house. She could have married again; she had money and was young and attractive for a big woman. What she did was to pick out Miriam from an orphanage and adopt her as the daughter she had not had with August Hennessey.

I was ten when Pa died of pneumonia. Ursula drove all night from West Amber to Cleveland. Miriam was with her—a skinny, black-eyed girl of eight who terrified me by throwing her toothpick arms around my neck and kissing me and calling me her big brother. I pointed out to her that, if anything, she was my niece by adoption, but that actually she was nothing at all to me. I also told her that I disliked girls, especially being kissed by them. Which was true at the time, but not for long.

Ursula buried Pa and packed my things and the three of us drove east. When the car climbed Mandolin Hill and I saw the ivory-and-blue frame house, I felt that I was coming home, although I had never been there before. And in a few days it was home, and had been until four years ago when I had enlisted in the Air Force.

NOW I was back, eating as I had so many hundreds of times in the pine-panelled dinette with Ursula and Miriam. But this was no longer all of my family. I had a. wife who should be here or with whom I should be.

Abruptly I put down my knife and fork.

"Lily knew within a few days when I'd get in," I said. "She'd hang around waiting for me. Or if she went away on a visit she'd leave word where I could find her."

Ursula reached for my plate to fill it with a second helping of roast lamb and apricots, which nobody in the world could cook the way she did. "I'm not responsible for your wife, Alec. We'll discuss her after dinner."

"So there is something to discuss?" I said.

She dipped her head to slice the meat. Miriam ignored the food on her plate to watch her intently. Then Ursula handed my plate to me and said to Miriam: "What have we ever done to him to make him snap at every word we say? Does he think we murdered his precious wife and buried her in the cellar?" She turned an angry face to me. "There's a great deal to discuss. You'll have to start planning for your future."

It was an old trick of hers to turn my words back at me and making them mean something altogether different. "I never said you haven't been swell to Lily and me. You've supported me for all those years and—"

"Pa left his insurance to you."

"You saved it to see me through college. Then I brought my wife home, whom you'd never seen before, and you kept her here with you for two—"

"You've been supporting her through your allotments," Ursula said. "I made sure that she contributed to household expenses. Do you know that Kerry Nugent is back?"

I finished the mashed potatoes in my mouth before answering. "He left later than I did, but he flew while I came by ship. Where is he stationed?"

"He's home on sick leave," Miriam told me. "He's been here several times and he looks fine. When you called yesterday that you'd be home tonight, I tried to get in touch with him to tell him. But his mother said he'd gone to New York."

"New York," I muttered. Lily was in New York. Kerry had met Lily at the same party I had and he'd tried his best to make her. What the hell was the matter with me? Kerry wouldn't pull anything like that. If he had had anything to do with Lily since his return, it would be to slap her ears off for the way she had treated me. Sure. That would be Kerry.

"He told us all about that last flight you two were on," Miriam was saying.

The food turned to straw in my mouth. "Did he tell you how I smashed his ribs and killed Ezra Bilkin?" They stared at me.

"What are you talking about?" Ursula said. "Who is Ezra Bilkin?"

"He was our flight engineer. He died because I lost my nerve and lost my way home."

"Alec, that's not what Kerry said." Miriam leaned against the table, her grave black eyes filling her face. "Kerry was pilot; he ought to know. He said that after your radio was shot out no other navigator could have got the plane back to land. He said that if anybody else had been navigator everybody in the plane would have been killed."

"Ezra Bilkin was a swell guy," I said. "He had a wife and two kids in Indiana. It was my job to bring the ship home safely and I muffed it."

"But you'd brought it back so many times before," Miriam argued. "Kerry said you and he flew twenty-three combat missions before—"

"Before I lost my nerve," I said. "Before flak shook us like a cork in a storm and a Zero planted a bullet an inch from my ear. Suppose the radio was gone? A schoolboy can take a B-29 home on a beam. I went to pieces. Why do you think they grounded me?"

URSULA reached across the table and firmly gripped my hand. "There's no need to shout, Alec."

So I was shouting again! I was shaking all over and the food I had eaten was bouncing in my stomach. I jerked my wrist away from Ursula and clutched the edge of the table with both hands. I'd never before had it as bad as this. Major Goldfarb, the chief flight surgeon, told me I'd be fine if I avoided undue excitement for a while, and that even if I got these attacks they were nothing to worry about. But Ursula and Miriam looked at me as if watching my dying convulsions.

"I shout," I said bitterly, "so I'm a mental case."

"Nobody ever said—" Miriam started to protest and then gave it up.

I pushed back my chair and stood up and went through the swinging door into the kitchen. Then Miriam called: "Alec, please come back and finish eating."

"Let him go." Ursula spoke in a half-whisper, but I heard it in the kitchen. "The trip upset him. He'll be better after a rest."

"Trip nothing," Miriam said. "It's Lily. Ursula, aren't you going to—"

"Later," Ursula said. "After he calms down."

Their voices dropped still lower and I couldn't distinguish words. I crossed the kitchen to the door at the other end and went up the hall. The doorbell rang before I reached the foot of the stairs. I opened the front door and three men entered. Two of them I knew—Oliver Spencer, who had been at the station when I arrived, and George Winkler.

Years ago Miriam and I decided that George Winkler would marry Ursula the moment she wanted him. He was a bear of a man, big and shaggy, with small bright eyes that crinkled readily and a broad nose that wrinkled when he was amused. He was the most prominent lawyer in West Amber, which sounded more imposing than it was. For a long time now his romance with Ursula had trickled on placidly, without change or interruption, if it was a romance. Perhaps Miriam and I were all wrong and he had dinner at our house once a week and was the mainstay of Ursula's Saturday night poker games only because an aging bachelor needed an anchor somewhere.

He greeted me as a father might, pounding my upper arms with his large open hands.

"I see you were in a hurry to get back into civilian clothes," Oliver Spencer observed. "How do you feel in them?"

"Fine."

"That's the way it was when I came home from the last war," George Winkler said. "I couldn't wait to dress in something with color in it. Do you know Owen Dowie, Alec? I guess not. He comes from the other end of the county and was elected sheriff only last year."

THE third man stepped forward to shake my hand. Blame Western stories for the assumption that a sheriff is a gaunt, gimlet-eye man with a gun swinging from his hip. Sheriff Owen Dowie looked like a mild and somewhat scared bookkeeper. He had a pinched, rather intense face and pale, myopic eyes peering through thick shell-rimmed glasses.

"Heard a lot about you, Linn," he said. "I'm told you can make the cards stand on end and call you brother."

Mr. Spencer chuckled. "I'll lay you ten to one Alec can deal you any hand you ask for and you'll never guess how he did it."

"I'm out of practice," I said.

"What's the matter, didn't you find suckers in the Air Force?" Dowie asked with a shadowy smile.

There was a silence. Then George handed Dowie a glare. "Alec never played a crooked hand in his life except to show how it was done."

"I was only kidding," Dowie said hastily. "I mean, a player like you should've had a good thing with all the poker played in the Army. One man I know came back from Italy with five thousand dollars in winnings."

"I hardly played," I said.

Mr. Spencer patted his bald head. "Well, I've been able to take you over now and then, Alec, and I'm looking forward to bucking you again tonight."

"I'm sorry, but I'm not playing tonight," I said.

Ursula came into the hall and apologized for having finished dinner so late. Would they wait downstairs in the cardroom until she and Miriam cleaned up? The three men went down the hall to the basement door under the staircase, and for the first time since my return I was alone with Ursula.

"All right, let's discuss," I said.

Almost she seemed to squirm.

"There's no rush and I can't keep my guests waiting. Why not take a hand in the game? It will take your mind off—" She stopped.

"Off Lily?" I said. "No, thanks."

I WENT outside. It was not quite dark yet and the moon was a squeezed lemon low in the sky above the lights of West Amber. I crossed the front of the house and walked up one of the gravel paths through the flowerbeds.

It was the middle of July now, but it had been as mild as this on those two early May nights when Lily and I had walked here. We'd had our arms about each other and now and then we stopped to kiss. We walked all the way to the rickety bench where the grape. arbor used to be before it fell apart, and we sat there and necked like two high school kids.

The Lily I called her. She was like one, tall and slender and all of her so very white, even her hair which was platinum, and that night even her skirt and blouse were white. The smell of her hair was in my nostrils and my mouth tasted of the perfume that was in her lipstick. Her face was small, elfin, and lovelier in moonlight than I had ever seen it, and it was always turned up to me.

That was what I had wanted to come home to. Not the Lily who wrote bored and often nasty letters, when she bothered to write at all, but the white Lily of that night. My ardent wife with the elfin face and the sweet eager body.

We had necked on the bench like two adolescents and then had gone up to our room. That was our last night together. There had been two other nights—the first in a New York hotel after we were married and the second here in my room.

Walking alone in the garden now, I had almost reached the bench. I stopped dead and turned to look at the house. That side of it was dark except for light in the kitchen and in the basement cardroom. There were three bedrooms upstairs—Ursula's and Miriam's and mine. Lily, of course, had been given my room when I left. It had been our room for two days and nights.

I found myself running back to the house. A minute or two would make no difference, but I ran and I was breathing hard when I burst into my room.

My room. A man's room. Obviously not a room in which a woman lived.

I hadn't guessed earlier that evening when I had changed my clothes. Because for so many years it had been exclusively my room, shared with nobody, it hadn't occurred to me that it should have been different, that in twenty-two months it should have ceased to be a man's room and should have become a woman's room.

I tore open the closet door. No dress, no skirt, nothing that was a woman's. No cosmetics and brushes and combs on the dresser and no women's stocking and undergarments in the dresser.

Lily didn't live in this room. She didn't live anywhere in this house. They had lied to me. Ursula was afraid to tell me the truth, whatever it was.

CHAPTER III

Blood on the Lily

THERE WERE SUBDUED voices in the living room. I went in there instead of down to the basement. On the couch in front of the dead fireplace Bevis Spencer was holding Miriam's hand. He turned his head sharply when he heard me and dropped her hand in confusion and clambered up to his feet.

"It's swell to see you back," he said, grabbing my hand between his two palms.

My throat made polite noises of greeting.

Bevis was Oliver Spencer's son, but in no way like his small, bald, go-getter father. He was a head taller and had a thick unruly mop of hair which would last forever and he was awkward and embarrassed with strangers. He had opened-up only a little since our high school days when he'd been a moody, unsmiling boy who kept more or less to himself. The only reason I had come to know him fairly well was that in those days I had a crush on his sister Helen and spent considerable time in the Spencer house.

"I begged the Army doctors to pass me," Bevis was saying, "but they refused. I'll always feel I missed something big."

"You missed something all right," I told him, "You'll never know how lucky you were. Do you mind if I speak to Miriam alone?"

She had been pushing back her hair from her brow and readjusting her bun. When I said that, her hands paused at the sides of her head, but she didn't look up at me.

Bevis glowered at me. Glowering came easy to those deep-set eyes under overhanging brows. "I was on my way downstairs anyway," he said without enthusiasm. "They have only four hands and I promised to make a fifth."

I waited until he was out in the hall before I turned to Miriam. She spoke first.

"Bevis wants to marry me, Alec."

That was why he had glowered at me. I'd be sore too if somebody had barged in at a time like that. I told her that I was sorry that I'd come in at the wrong moment.

"It doesn't matter," he said. "Bevis has been proposing to me about once a month during the last year. I'd just put him off again."

"He's too gloomy for you."

"He brightens up a lot when you know him well. He's intelligent and considerate and sweet."

"So what's wrong?"

Miriam didn't answer. She stood up and went to the table and took a cigarette out of the translucent plastic cigarette-box. I noticed for the first time since my return that she'd put on weight. Just about enough weight. She had been too skinny since childhood and now her figure was pleasantly mature and her angular face no longer had that pinched look. She was a very attractive girl. Not beautiful like Lily or Helen Spencer and perhaps not even pretty if you took her features apart, but the black-eyed, dark-skinned animation of her face made up for it.

"I don't know what to do, Alec," she said after a pause.

IT WAS my duty to be the sympathetic confidant and advisor and discuss her problem with her far into the night. I was the man oi the household, the nearest thing to a father or brother she had. But I had a problem of my own which was a lot more urgent than hers. To me, anyway.

"Where's Lily?" I demanded.

She took the unlighted cigarette from her mouth. "Ursula told you."

"Cut it out!" I realized I had shouted that and lowered my voice. "Lily isn't living in this house."

She put a match to her cigarette. She had trouble getting a light. Then she said: "No, she isn't."

"What's happened to her?"

"Don't get frightened. She's in the best of health as far as I know."

I gripped her arm. She uttered a little exclamation and I loosened my fingers. "She walked out on me, didn't she?"

"No, Alec, she didn't. She—Ursula—" she drew in smoke and made a fresh start. "Ursula asked her to leave the house."

"Why?"

"You'd better ask Ursula."

"When did this happen?"

"Two weeks ago."

Panting, I stepped back. It wasn't Lily's fault that she hadn't met me at the station. That was good to know.

"Where's Lily now?"

"She's living somewhere right here in town."

So Lily hadn't walked out on me, as for almost a year now I had thought she might. She could have moved back to the bright lights and gayety of New York when Ursula had kicked her out. Instead she had remained in this dull town where I would be able to find her at once.

I struggled to keep my voice under control. "You mean to say that you didn't let Lily know that I was coming home today?"

"Ursula wanted to have a talk with you before you saw Lily."

"About why she threw Lily out of the house? Why did she?"

Miriam brought the cigarette up to her mouth. It trembled against her lips and she tossed it into the fireplace. She was nearly as upset as I was. "Ursula will tell you."

"Why didn't she tell me before this?"

"She wanted to break it gently."

"Because she thinks I'm a mental case and wants to cushion the shock?"

MIRIAM put a hand on my chest. Her dark, intense eyes were misty. "Please, Alec, try to understand how we feel. Ursula is anxious that you hear our side first. She planned to have a long talk with you after dinner, but then the men arrived for the poker game."

"So poker is more important than I am? Is that it?"

"Alec, that's not fair."

"All right," I conceded. "So she found excuses to put it off because she was afraid to tell me. She thinks I'm not in a fit mental state to take bad news. It must be pretty bad if Ursula kicked her out of the house. It was because of a man, wasn't it?"

She reached for another cigarette, although she hadn't taken more than a couple of puffs on the one she'd discarded. "Ursula will tell you all about it."

"She had her chance. What's Lily's address?"

"Alec, please have a talk with Ursula first."

"Where is Lily staying?" I yelled.

"Ursula asked me not to say anything until she—"

I swung away from her and went out to the hall and ran down the basement stairs.

The cardroom took up half the cellar and was more cozily furnished than any other room in the house. It had an oak floor and a beamed ceiling and was panelled in cedar. There was a tiny bar in one corner and a radio and a couple of leather lounge chairs in another and at the far end of the room a bridge table which was seldom used. The round poker table, big enough to seat ten players, dominated the room. The red leather chairs were custom-built for a person's bones and the neon lights were as soft as a summer dawn.

Sheriff Owen Dowie was dealing when I burst in. They were playing stud and Dowie's arm paused in midair as he was about to slide Bevis Spencer's fourth card across the table. There must have been something in my face that made Dowie and Ursula and George Winkler, facing the door, stare at me. Oliver Spencer and Bevis Spencer turned in their chairs and added their stares to the others.

I said: "Ursula, where is Lily staying?"

She started to rise from her chair. "I told you—"

"You lied," I said. "She's in town."

Ursula rose all the way and flashed an angry look over my shoulder. Miriam had followed me down the stairs and stood behind me, just inside the doorway. Ursula turned back to the table. "I'm sorry, gentlemen, but you'll have to excuse me for a few minutes."

"I don't want to break up the game," I said. "I only want to know where to find my wife."

Ursula came around the chair and took my arm. "Let's go upstairs, Alec," she said in the gentle tone one uses to a sick child.

"Like hell!" I said. "All I want to hear from you is Lily's address."

"Alec, if you'll listen—"

I shook her off and went up to the table. "Some of you men must know where Lily is. Bevis, you can tell me."

BEVIS dropped his eyes to his cards. He had a seven and a queen showing, and the card which Dowie still held in his hand would be his second queen. Dowie was peering curiously at me through the thick lenses of his glasses. George Winkler fumbled with a cigar wrapper. Oliver Spencer brushed back nonexistent hair on his head.

"You're all in on this!" I said. I was shouting. I'd been shouting since I entered the room. I didn't care; I'd keep on shouting. "Don't think I'm a dope. I've an idea what Lily was up to while I was away. It was between the lines of everything she wrote me. But now I'm back, and, by God—"

My voice choked off in my throat. This wasn't any of their business. It was too personal to invite anybody in on my agony.

There was a brittle silence while I pulled out my handkerchief to wipe my sweating face. Then George Winkler sighed as loudly as a gust of wind sweeping through the room.

"Alec, she's not worth it," he said.

"None of your damn business!" I flung at him. "I don't need any of you to tell me how to handle my wife. Where is she?"

Ursula was back at my side, clawing at my arm. "Alec, control yourself. If you'll come upstairs with me for just five minutes—"

"Why should I control myself? Where's my wife?"

Suddenly she looked very tired. Her broad shoulders drooped. "Have it your way. She's staying in a bungalow on James Street."

"Thanks," I said bitterly and turned to the door. Miriam was still standing there. She stepped out of the way and I brushed past her and raced out of the house.

A coupe was swinging into the driveway when I reached the road. Somebody called my name and the car stopped broadside to me. By the dash light I saw Kerry Nugent behind the wheel and Helen Spencer beside him.

They'd come to visit me, of course. Kerry would ask me how I was and I would ask him how he was and he'd tell me the latest news about airmen we knew all over the world and whom you were always running into or hearing about and how soon he expected to return to active duty. I did not want any talk at all tonight except with Lily, and not too much talk with her.

I said, "I'll see you tomorrow, Kerry," and moved past the coupe and out to the road.

"Alec!"

I glanced back. Kerry had the door open and one foot out. I put my head down and walked as rapidly as I could without quite running, fleeing from the conspiracy to keep me from my wife's arms.

AT THE bottom of the hill I paused. James Street was two miles away, yet I'd run right past Ursula's car which was still parked in the driveway. I was a guy in such a terrific hurry that I was taking ten times as long walking as it would to drive. I hadn't even had sense to bring along 11 flashlight.

It would still save time to go back for the car, but some of them might be outside the house and I couldn't face them again. Not now, anyway. I walked on and came to the fifteenth tee of the golf course where it angled toward the road. As kids we used to take a short cut diagonally across the course to the second hole, saving perhaps half a mile. I climbed the stone boundary wall and by the sickly light of the waning moon started across the fairway.

George Winkler had said that Lily wasn't good enough for me or not worth it or something like that. Whatever it was, he had put into indefinite language the vaguer fears caused by her letters or not hearing at all from her for weeks. Did George know or had he handed me town gossip? And would Ursula have kicked her out without certain knowledge?

Face it. Two years ago she was your wife for three days and nights and after that you were strangers who didn't again see each other. While you yearned in loneliness and faithfulness at the other end of the world, she did not keep her bed always empty. What were you going to do about it?

Nothing.

Nothing tonight and perhaps nothing tomorrow or the day after that. I wanted her. I hated her and wanted her, as I had hated her and wanted her for along time now, submerging dread and fear in the memory of those three nights and the never-ending hunger for her.

I'd use the Lily's beautiful body. I'd satisfy my need for her. And after that-

I didn't know. I didn't want to know tonight.

At the second hole I came out on Old Mill Road at the edge of town. My watch said seven minutes to ten. Too early for her to be asleep. I would like that, finding her in bed and waking her with kisses.

But suppose she didn't want you? Suppose her body had no more ardor for you than her letters had had?

By God, I'd take her anyway! Brutally. I'd hurt her. I'd—

I stopped to catch my breath. I hadn't been walking rapidly since I had reached the bottom of the hill, but all the same I was drawing air into my lungs with labored gasps. I fumbled out a cigarette, lighted it, and the smoke felt good inside me. I walked along the clearly defined macadam road.

JAMES STREET. It wasn't actually a street; there weren't any in West Amber except for the three which comprised the business section. It was a tar road. Along either side houses were spotted at varying intervals. There was a mile of it, and like a sap I'd left the cardroom without asking just where on James Street Lily lived.

A car approached. I stood in the middle of the road and waved in the hope that whoever was in the car could tell me where to find her. The headlights bore down on me. The car did not slacken speed; it seemed determined to run me down. I jumped and felt the wind of its passing.

I cursed the driver for a madman, glad to be able to curse something, and went on. The mailboxes stood on the right side of the road? One of them should bear her name. I struck matches to read the boxes, passing up those in front of houses in which I knew she could not be because they were too large or I knew the people who lived in them.

Like George Winkler's white brick house. When I passed it, light went on in an upstairs room. That would be Amy Winkler, George's spinster sister who kept house for him. She knew everything there was to know in town. She would tell me, but she would also gush over me in greeting. I kept walking.

Two boxes farther on I came to it. The name JOSEPHS was crossed out with black crayon, and under it was waveringly printed: LILY LINN.

Linn. My name. The name I had given to my wife.

It was suddenly very good to be home. The fact remained that she had stayed on here in West Amber to wait for my return. That was all that counted. The rest was merely an inability to write letters as passionate as her embraces. She was waiting for me and I was coming to her.

It was a neat little stucco bungalow . just off the road. Every window was lighted. With both hands I brushed back my wild hair and ran my handkerchief over my face and went up to the door. I flicked my tongue over my dry lips and knocked.

There was no sound in the house. She wouldn't have gone out and left all the lights on. Perhaps she had dropped off to sleep while reading. The door was unlocked. I pushed it in.

The door opened directly into a small living room. I saw her at once. She was lying on the floor at the side of a reed couch.

I closed the door behind me and walked slowly into the room, not thinking, not feeling anything except something jumping in the emptiness inside of me.

She was on her side, turned away from me, her knees bent. I squatted beside her and put a hand on her shoulder.

Then I saw the knife in her breast. I reached over her shoulder and grabbed the handle and started to pull the knife out. It came out easily. It came halfway out, and suddenly I jerked my hand away from the knife as if it had turned glowing hot.

The truth hit me like a kick in the stomach. The Lily was dead. Nobody lives with a knife in his heart.

I straightened up beside her and at once my knees started to bend. I sank down on the couch. The room wavered. I put my head in my hands, closing my eyes tight against the darkness of my palms.

IT WAS very still. Somewhere a clock ticked. I dared take my hands from my face and the room had straightened out. My head remained bent; I was looking down at her legs.

One foot was covered by a satin mule. The other foot was bare and the mule which belonged to it lay behind her. She wore no stockings and the nails of her toes were scarlet. The first time I had ever seen her without any clothes on I had, oddly, noticed first of all her painted toenails. They had shocked me a little and excited me.

She was wearing the heavy silk hostess gown with the tawny-orange tiger lilies. I had bought it for her the day we were married. Lilies for Lily, I had said. A poor joke, perhaps, but the kind you delight in on honeymoons. During all the breakfasts I'd had with her, the first in the New York hotel room and the other two at home, she had worn it. The hem had hiked up on her body and her uppermost thigh was naked. It was a lovely thigh, smooth and rounded, and even now I could remember the ?rm warm feel of it.

Sitting bent over, that was all I could see of her. I didn't want to see any more, but I had to. I raised my head an inch and let my eyes move up the crumpled form.

The knife protruded from the swell of her left breast. The dull black handle of a kitchen knife. There was a tiger lily on each breast, and I remembered telling her one morning that those two, and one other, were my favorite lilies of all the many on the hostess gown. The knife had pierced the one over her left breast, and it was no longer tawny-orange. Her life had dyed it red.

My eyes remained on the bloody lily, not wanting to look higher. A body is a body, living or dead, but a face—

I looked. Her face was no longer beautiful, no longer elfin—no longer anything but dead.

Then the shakes got me, as badly as that first time when we'd jumped from our gasless plane and I was bending over Kerry Nugent who was tangled in his parachute. Joe Klintcamp, the copilot, had slapped me and that had helped. There was nobody to slap me now. I dropped my head and shook and felt sweat cover me.

It didn't last long. It was passing when I heard the door open. I looked up and Sheriff Owen Dowie stood in the doorway peering myopically at Lily.

He didn't say anything at first. He closed the door and came forward and knelt beside her. Then he shifted his gaze up to me. His pinched face was sad.

"I'm sorry about this, Linn," he said.

I hadn't heard the sheriff's car, but I heard the second car pull up. We both turned our heads, listening to a car door slam. Then there was a knock and a man said: "Alec?"

Dowie looked at me to see what I would do about it. I just sat there.

The knock came again. "Lily?"

Dowie said quietly: "Come in."

It was Kerry Nugent. He gawked at Dowie in surprise and took a step or two into the room before he saw her. "Alec," he said weakly. He came on to Dowie's side. "Is she dead?"

"He stuck a knife in her heart," Dowie said.

He? Whom did Dowie mean? I heard the clock. Why were they so very quiet?

"You don't think—" I said. Their faces told me what they thought. "My God, I didn't kill her!"

Kerry turned his eyes away from me. "I'm sorry, Linn," Dowie said again.

CHAPTER IV

The Jail

URSULA STOPPED INSIDE the cell and sent a startled, shocked glance over her shoulder at the door closing behind her. Then she kissed me quickly on the mouth and thrust a package into my hands, like an embarrassed little girl presenting a gift at a birthday party. "One of your chess sets," she said.

"Thanks." I tossed the package on the cot and led her to the wooden chair. "Sit on that. It's softer than the cot."

Her big frame perched unrelaxed on the edge of the chair. She looked about. A second was enough to take in everything there was to be seen. She shuddered. "How horrible for you!"

"A bit cramped," I conceded, "but the food is wholesome and the turnkey does little favors for me if I keep his palm greased. My chief complaint is that a vicious character like me is allowed only two visitors a week, not counting lawyers."

"And they wouldn't let me visit you at all the first week and they wouldn't let Miriam come up with me." Ursula removed a fleck of tobacco from her lip. "I'm glad that you're taking it so well, Alec. I was afraid—I mean—"

"That I'd crack wide open?" I said. "That I was a psychoneurotic even before they tossed me in here and that I'd pound on the door and chew the mattress?"

"Alec, please! "

"All right, I'm scared," I said. "There's still a trial between me and the death house, but the last time the district attorney talked to me he was already gloating over the two thousand volts of electricity which—"

"Alec!"

I stood up. I walked the five paces to the other end of the cell and lit a cigarette. I was sweating, but not much, and my hand was not unsteady. I returned to Ursula.

"I can take it," I said. "It's easier than sweating out a mission. The odds against me aren't much greater than trying to get home after bombing Singapore. George Winkler hasn't been around in a couple of days. What's he doing about me?"

"I want to talk to you about that. We've retained a very big lawyer from New York named Robin Magee."

"What's the matter with George?"

"He will be associated with Magee. George does not think he has had enough experience in criminal law, and Robin Magee is supposed to be marvelous."

"Expensive as hell, I bet."

"Does that matter?"

"I'm grateful," I said. "When I get out and start earning a living, I'll pay you back. It'll cost more than you think. Is George hiring private detectives?"

"Why private detectives?"

"To find the murderer, if possible. That's what the police should be doing, but they're so sure that I'm the one that they're not bothering."

SHE didn't say anything. I sat down on the cot and stared at her. Her eyes lifted; there were tears in them.

"So you agree with the police," I said slowly.

She propelled herself out of the chair and flung her arms about me. "Alec, it's my fault. I should have had that talk with you as soon as you got off the train. I kept putting it off. I wanted you to rest after your journey. But I only made it worse for you. It must have been such a shock when Miriam blurted it out to you."

"Let Miriam alone," I said. "She didn't tell me anything."

She pressed her face against my arm. "I never liked Lily, especially not for you, but I should have let her stay in the house until you came home. It was only a couple of weeks."

"Was Lily cutting up as badly as that?"

"There was gossip."

"Is that all?" I said. "Nothing but gossip?"

"Well, she was seen drinking with a strange man."

"Damn it!" I was on my feet, pacing the cell and slamming my left palm with my right fist. I wanted to break somebody's neck, but I didn't know whose. "Just gossip. Just drinking with another man. She didn't walk out on me even after you kicked her out. She stayed around to wait for me."

Ursula's jaw hung slack. "You thought from my actions that she was carrying on an affair with somebody else? Oh, God! If I'd minded my business—"

I swung to face her. "I wouldn't have rushed off to kill her? You believe that, tool"

The door was flung open. The beanpole turnkey stood there. "What's the yelling about?"

I took a deep breath. "I got excited. It's nothing."

"Well, the lady's time is up. If you want any more visitors, Linn, keep it quiet."

Ursula turned a rigidly set face up to me to be kissed. Her lips were cold. "Alec," she said, "I know you're not a murderer."

"Sure." I squeezed her arm. "Get the idea out of your head that Lily was murdered because of anything you did or didn't do. It had nothing to do with you or me. Remind George Winkler about hiring private detectives."

"Time's up, lady," the turnkey said. Ursula nodded dully and went.

I WASN'T sure what there should be about a lawyer to inspire confidence, but Robin Magee didn't in me. He was a tall, slightly stooped man with hair graying aristocratically at the fringes, and he was dressed like an actor or an English politician. His breath smelled of very good liquor.

George Winkler sat on the chair and I on the cot. Robin Magee remained on his feet and tossed me a benign smile. "Now let's hear your story, my boy."

"I told it to the district attorney and I told it to George," I said. "It hasn't changed since then."

Magee nodded amiably. "It may be that you will mention something in the retelling which you overlooked before."

So I told it again. There was surprisingly little. I had walked in and found Lily with a knife in her heart.

There was a silence when I finished. George looked up at Magee. The great criminal lawyer from New York smiled silkily.

"Why did you touch the knife-handle?" he asked.

"I started to pull it out. Then I realized that she was already dead."

"The knife was in her heart. Didn't you see that?"

"My brain stopped working for a few seconds."

Magee studied the ceiling. "They tell me you are a very bright young man. You must have known that it was not proper to touch a murder weapon, and that pulling the knife out wouldn't have helped her even if she were still alive."

"I wasn't in a state to realize anything."

"You were a soldier. You must have seen many dead people."

He sounded a lot like District Attorney Hackett questioning me, but he was being paid to be on my side. I said: "I've seen dead men, but I've never before walked in on my wife with a knife in her heart. Did you?"

Magee chuckled. "Naturally not."

"Then how the hell do you know how a man will act at such a time?"

"You were a navigator of a Super-fortress," he argued. "You were trained to keep your head in an emergency."

"There was nothing in my training about how to act when I found my wife murdered. What are you getting at, anyway?"

George put in: "Didn't the D. A. ask you those questions?"

"Yes."

"We've got to know what you told him, don't we?"

"That's right," I agreed. "Okay, throw 'em at me."

Robin Magee dropped down on the cot. He did not hold my hand, but his manner was so intimate that he might have. His breath made me thirsty. "It looks bad, my boy. There's no getting away from it. There are many witnesses that you left your house in a highly excited state of mind—unfortunately, one of them the sheriff. Then you were found bending over the body—"

"I was sitting on the couch."

"You were sitting on the couch and she was at your feet. And the police laboratory found your fingerprints on the knife and no other prints."

"The murderer had wiped his off."

"Let us grant that. This morning I had a talk with the D. A. He did not tell me in so many words, but he implied that he had even more definite proof than the medical examiner's report that she had been alive a very short time before Sheriff Dowie found you there. He gave me this much to induce me to accept a second-degree plea."

"Did you tell him to go to hell?"

"In effect, yes." Magee tapped my chest with his knuckles. "My boy, Winkler and I are going to get you off absolutely free. You may have to spend a month or two in a sanatorium, but even that will probably be unnecessary."

IT TOOK time to penetrate. I looked from one pair of eyes to the other, both pairs watching me anxiously. Then I left the cot to get as far from them as I could, and turned at the wall.

"So that's it," I said. "I'm insane."

"Not at all." Magee's honeyed words ?owed to me. "Temporary insanity, perhaps. Extenuating circumstances, certainly."

"In other words," I said, "confess that I murdered Lily."

George shambled his bear's body over to me. The fatherly act. The close family friend. I knew what he'd say before he said it. "Alec, you know I'll agree only to what's best for you. Magee is one hundred percent right. He's thought of the only way to get you off."

"Get out!" I said. "Both of you!"

George's small eyes blinked in pain. "Alec, as your attorneys—"

"I don't want lawyers who are convinced I'm guilty. Get out!"

He turned to Magee for help, and the great lawyer gave me his smooth smile. "Naturally he's upset, Winkler. He'll be more reasonable tomorrow. Goodbye, my boy."

"Don't come back!" I flung after them. "

For a long time I stood looking at the door after he closed it. My teeth were chattering. I gritted them and threw myself face down on the cot. The walls of the cell closed in on me. I could not breathe.

. . . They returned the next day. I had told the turnkey not to let them in, but he did. I lay on my cot and stared up at the ceiling and pretended not to hear them as they talked down at me. As a matter of fact, 1 heard very little of what they said. After a while they left.

KERRY NUGENT came in briskly. He grinned down at the chessboard, on the chair.

"What's the problem?" he asked.

"White to mate in four moves."

He studied the board. "You're even better than I think you are if you can do it."

"I have plenty of time," I said.

"I guess you have." He sprawled down at the foot of the cot and nonchalantly dug out his pipe and pouch. It was all as casual as a visit to my bunk after we'd slept off a mission.

You may remember a photo in Life of a square-jawed, rugged-faced bomber pilot standing under a wing of a B-29 Superfortress in an India base. That was Captain Kerry Nugent. The moment the photographer's eyes fell on him he tabbed Kerry as the idealized type of grim and nerveless American manhood who was bringing death and destruction to the enemy.

"How are the ribs?" I asked.

"As good as new, practically, except that I'm still taped up like a Prussian general in a corset." His face clouded. "And stop talking like a heel about it. Miriam says you're shooting a line that you lost the plane."

"I did."

"I'll break your damn neck if you don't cut it out." Kerry sat up. "What the hell! I ought to have my head examined for bringing it up. How about a game of chess?"

"Your time will be up in a few minutes."

"Not for Mrs. Nugent's boy. I slipped the turnkey a five spot. That ought to be good for a couple of hours. Give me a knight and a bishop and I'll try to make a game of it."

I dumped the chessmen into their box. "I don't want my mind taken off anything. I want to talk. How did you happen to show up at Lily's place only a few minutes after I got there?"

His right cheek ticked. It was an old sign of annoyance. "Why kick it around? Forget about her. She got what she deserved."

"Why did you go to Lily's?"

Noisily he drew flame into his pipe. "Miriam sent me. I'm a good soldier. When a lovely lady gives orders, I obey without question."

"That's no answer."

"I suppose it isn't," Kerry said, suddenly grave. "I'm not quite straight on it myself. I'd gone to New York for a couple of days. I got home around eight and my mother told me that Miriam had phoned earlier that you were expected home that day. I called up Helen and she'd heard from her father that you were back and she wanted to see you too, so after I ate I picked her up and we drove over."

"You and Helen Spencer," I said. "That's something new."

HE GRINNED shyly. "About six days. Well, you know how you acted when we drove up and saw you coming out of the driveway. We drove on to the house and found everybody out on the porch talking about you."

"So I broke up the card game?" I said.

"You sure did. I heard Mr. Spencer ask Ursula if she wanted to resume. She shook her head and stood looking out at the road. Then Miriam pulled me aside and told me what had happened. It didn't sound like much to me. Why shouldn't a guy raise hell when he isn't told where his wife is? Why shouldn't he dash off to her? But Miriam said I hadn't seen the way you looked and acted. She was plenty worried. She gave me the idea that the place for you was a straitjacket, or anywhere but with a wife who'd been playing you dirty." He paused and then added: "That's throwing it at you bluntly, but you wanted it."

"You're doing all right. Go on."

"That's about all. I argued for a while. You had every right to go dashing to your wife's arms. Then Ursula joined the argument. I was your bosom pal; we'd faced life and death together; you'd resent my horning in on your affairs less than anybody else. That line. They weren't sure what I should do when I caught up with you. I guess sort of hang around to keep you out of trouble and bring you back to the old homestead if Lily spat in your face, as they more or less expected. So I went."

"Where was Sheriff Dowie?"

"He'd driven off. So had Bevis and his old man. Maybe George Winkler too; I don't remember. But when I left, all I noticed on the porch were three women—Helen and Miriam and Ursula."

"I walked all the way," I said. "Why didn't you reach Lily's before I did?"

"That's why I'm kicking myself now. But I didn't hanker to barge in on you two in a fond embrace. My idea was to catch up to you on the road and maybe talk to you and calm you down or go to Lily's with you if you didn't object strenuously. So I crawled along the road in my car looking for you. When I reached the head of James Street, I decided that you couldn't have walked there so soon or even run there and that I must have missed you on the way."

"I cut across the golf course."

"Hell! I should have thought of that. I drove back slowly, still looking for you. When I reached the bottom of Mandolin Hill, I turned around and tried again, figuring that somehow I'd passed you up in the darkness. This time I went all the way to Lily's. I saw a. car parked outside—Dowie's it turned out—and decided that it she was having company, why not me too?"

I SAT on the other end of the cot fingering the chessmen in the box on my knees. It was a cheap wooden set. The black king had lost his cross and a white rook was minus a couple of turrets. Ursula had kept my good sets at home; this one would do for jail.

"Had you seen Lily before that?" I asked.

"Since my return home?" Kerry appeared to be smoking matches instead of tobacco. "Once. My second day in. Paid my respects to my pal's wife. Told her you were okay and would be home any day. Drank a pair of cocktails she fixed and said so long. One of those duty calls. You know I didn't care one bit for her."

"You did that night we met her for the first time in New York."

"Oh, then. She was a lass with plenty of pulchritude in a low-cut dress. Something to try to make. You did and I didn't, so that was that. Besides, you married her, and that was okay by me, until what she did to you when we were in India. From then on she was marked lousy in my book."

"How did she sound when you told her I was coming home?"

"Drop it, Alec. She was no good. It's not the thing to say about a pal': wife, so in India I kept my lips buttoned. But now I'm telling you." He twisted on the cot to face me directly. "This might hurt, but I got the impression that for all she cared you could rot in India."

"It doesn't hurt," I said. "I'm sorry that she's dead, but that's all."

"So forget her."

"I doubt if the State of New York will let me."

Kerry groped in his pockets for matches. I tossed him mine.

"I could hand you a lot of boloney about that," he said after he had alight, "but I won't. I had a talk with George Winkler this morning. He's plenty worried about the trial, especially because you refuse to be sensible."

"I don't want to discuss it."

"Winkler is one of the people who would give their right arm for you. He knows what he's doing."

"No."

"Alec, you don't know everything. Ii it came to taking a three-star fix, I'd back you against any navigator in the world. But this is law."

"If that's all you have to talk about," I said, "you'd better go."

His pipe stem made bubbling noises. "I ought to push your teeth in," he said after a while. "But it's your life. Throw it away and the hell with you. Change your mind about :1 game?"

I submitted. We sat at either end of the cot with the board between us. I gave him a bishop and a knight, but ordinarily he needed more than that. Not today. I barely managed to squeeze out a draw.

MIRIAM came the day that Japan offered to surrender.

"Did you hear the news?" she said as soon as the door closed behind her.

"The turnkey told me. A lot of airmen I know are going to do a lot of celebrating at the thought of coming home." I felt my teeth in my lower lip. "I was the lucky one. I beat them back to the peace and security and comfort of home."

She moved all the way into the cell. She hadn't very far to go. As usual, she wore white. She knew what it did for her black hair and eyes and dark skin. This time it was a white shantung suit with a black blouse. Very snappy. And her manner fitted the outfit. Calculatedly cool and casual. Chin up and a forced smile. Carefully ignore the locked door and the gray walls too close together and the single gash of window.

"The surrender isn't official yet," she said, still topically conversational. "Everybody is praying it will be." She handed me a bulging paper bag. "Brownies which I baked for you this morning. With raisins, the way you like them."

At the last sentence her voice betrayed her. It started to quiver, and suddenly tears brightened her eyes. She stepped past me and dropped limply into the chair.

Visits were too few and precious to be thrown away with weeping over me. I could do my own weeping when I was alone. So I sat down on the cot and tried to bring up a subject which would interest her more than I did. "Made up your mind about Bevis Spencer?"

"How can I think about it at a time like this?" She gave me her profile. She didn't look well. Too much cheekbone showing. "Alec, why don't you let your lawyers help you?"

"Because I don't want lawyers who are convinced I'm guilty."

"They don't. George Winkler told me—

"So he sent you to talk me into it?" I said.

"We all want to help you."

"Sure," I said. "Like you tried to shelter me from my wife."

"That was a mistake. We should have overlooked everything Lily did until you got home."

"And now you all believe I'm a murderer and you're anxious to overlook that. You don't shy away from me in horror. You're loyal to the bitter end. And I'm not even grateful."

"We don't want gratitude. We want you back with us."

There was no point in chasing the subject around. I dug into the paper bag and pulled out a brownie. Miriam couldn't cook as well as Ursula—no-body could—but she could bake rings around her. "They're wonderful," I said and offered her the bag. "Thanks a lot."

She took one and sat nibbling it. Her eyes were far away. "Alec," she said remotely, "you must have loved Lily very much."

"Did I?" I let the idea simmer before I spoke again. "I don't think so. I hardly knew her. Six days in all, only three of them married to her. Those were fine days. I was going overseas, and I guess they would have been fine with almost any attractive woman with whom—" I stopped.

"I'm a big girl now," Miriam said into her brownie. "I understand. Please go on."

"Yes. And after that I was a million miles away and she was a woman to remember and dream about. If I was in love, it was with a memory."

"Alec, did you kill her?"

YOU HAD to hand it to Miriam. She at least came right out with it. N o- body else had asked me except the district attorney and the police. The others skirted around it, pretending to assume that I hadn't when they believed the opposite.

"No," I said.

She nodded. "You wouldn't lie about it if you had. Of course I believe you." But what was believing? You thought you did and you said you did, but that was just emotion. Cold reason didn't concur.

I took another brownie. "Did you send Kerry after me that night?"

"Yes. You frightened me. If Kerry had only met you! I mean, he would have gone there with you and he would have been a witness that you hadn't done it. Or if George had met you on the way."

"Did you send George also?"

"Only Kerry. The game broke up and we all stood on the porch for a few minutes. George had already driven away when Kerry left. The thing is that George lives on James Street, only a few hundred feet from Lily's bungalow."

"I saw him put a light on when I passed his house."

"He was so close," she said. "He blames himself now for not having waited for you on James Street or for not looking in on Lily. But how could he have known?"

"Did everybody leave the house after the game?"

"Well, Mr. Dowie was the first to drive away. Bevis drove his father home and came back a little later. Helen waited for Kerry to return. He was gone for more than an hour and then he brought the terrible news." She put a hand on my knee. "Alec, why don't you try to save yourself?"

"Back to the lawyers," I grunted.

"They don't want you to confess or anything like that. That would be stupid. George merely wants you to listen to him and Mr. Magee."

"I've heard what they have to say."

"You have to have a lawyer," she said urgently. "I understand that you can't plead guilt of murder even if you want to, so there has to be a trial and a defense. If George and Mr. Magee aren't your lawyers, the court will as~ sign one to you. Do you think you will be better off with a strange lawyer? George says that the district attorney is willing to accept a second-degree murder plea and that any other lawyer will snatch at it. George won't and you know it. He won't stop at anything to get you off free."

She did it very well. George Winkler must have coached her.

"The district attorney asked me to testify against you," she went on. "He has an idea that before you went down to the cardroom I told you Lily was unfaithful to you and that that was what made you so excited. I went to George and he told the district attorney that I would be a hostile witness and talked him out of a subpoena. So you see, George continues to work for you. That's why the court hasn't assigned another lawyer to you."

I sat hunched over on the cot with the bag of brownies between my palms. This was my third week of being shut in here with nothing to do but think. I'd been dealt a busted straight and the state held a pat hand and it was a pot I had to take or die. I was scared. I hadn't stopped being scared for a single minute since the state police lieutenant had told me I was under arrest.

The door creaked open. "Time's up, lady," the turnkey said.

Miriam sent him a frantic look, then turned her dark, wide eyes to me. "Alec, at least let George and Mr. Magee talk to you."

I stood up and so did she and together we walked the few steps to the door.

"Alec, please!" she said.

"All right, send them over," I told her wearily.

GEORGE WINKLER said: "Get the idea out of your head that we think you're guilty. It's only that the evidence is overwhelmingly against you. and we decided that there is only one way to get you off."

"By sending me to an insane asylum," I said.

"Nonsense. You misunderstood Magee. Even if that were the only way, we couldn't bring it off. The D.A. would stop us cold by bringing in psychologists."

"How will confessing to a crime I didn't commit help me?"

"That's not what we want either. All we ask is that you don't say anything before or during the trial. Sit tight. Leave it to us."

"I'll tell the truth over and over if I'm asked, by the D.A. or anybody else."

Robin Magee left the wall against which he had been leaning. "By all means, my boy. The truth. In my twenty-two years of law practice I have lost only one client to the electric chair, and I must say he deserved it."

"I'd as soon take the chair as a jail sentence."

"You haven't, a thing to worry about," Magee assured me placidly. "But I can promise to get you off free only if you don't interfere with my line of defense."

"Which is that I didn't do it."

"Certainly. Now, just relax. That's all we ask of you."

They prepared to leave, but I wasn't through with them. "George, did you hire private detectives?"

He looked blank for a moment. "Oh, yes, detectives. That's not necessary. Magee has a couple of topnotch investigators in his office."

"Are they doing anything?" I asked. "Have they learned anything?"

"If anybody learns anything, they will," Magee said. "They are digging into Lily's life."

I nodded. "That's the right angle. Maybe it was a boy friend who wanted her to go away with him when he heard I was coming home and he killed her when she turned him down."

They were not impressed. Magee said: "That is a possibility, but the coincidence is somewhat too pat. I mean, the murder occurring only a few minutes after you arrived, after having left your house in a state of—uh—high excitement."

We were back where we had been. They hadn't changed their minds; they were merely applying soft-soap. And who could blame them? My hand couldn't be worse and I couldn't improve it.

"Listen," I said. "A couple of days ago I remembered something. When I started down James Street that night, a car approached from the direction of Lily's bungalow. I thought the driver might be able to tell me where she lived and I flagged him. The car was going very fast on that bumpy road. It didn't even slow down."

George Winkler's bright little eyes glittered. "You think it was the murderer fleeing from the scene of the crime?"

"It could have been."

"How do you know the car was coming from Lily's house?" Magee argued. "You say you were at the head of the road. It might have been coming from any of the other houses or through from the other end of the road."

"The car almost ran me down," I said. "A fleeing murderer would be panicky if anybody tried to stop him."

"Did you see the license number? Do you remember the make of car?"

I shook my head. "The car meant nothing to me then. It might still mean nothing, but it's worth looking into."

"We certainly shall." Robin Magee glanced at his watch. "Take it easy, my boy. I promise you again that you have nothing to worry about."

More soft-soap. After they left, I stood at the window and thought about the car. It couldn't be traced. It was just a car, any car, passing in the night, and there was only my word that it had passed.

My word wasn't good for anything. To everybody it was the word of a murderer.

CHAPTER V

For the People

SUNLIGHT poured in through one of the tall courtroom windows and lay warmly over the long table at which I sat. When I held my hands in the dusty streamers, shadows formed on the table, and with my fingers I fashioned animated images of ducks and goblins.

George Winkler strode over from the jurybox where District Attorney Hackett and Robin Magee were examining talesmen. "Don't do that," he said.

"Do what?" I asked.

"Those tricks with your fingers. You look too nonchalant. You might give the jury the impression that you're hard-boiled."

"What's taking them so long?"

George chuckled. "It's a delight to see Magee work. He's challenging everybody who hasn't at least one son in the service. Wives of soldiers won't do, obviously, because Lily was the wife of one. Magee insists on sons, parents of boys like you. Hackett is challenging those Magee accepts, but it's a losing game for him because our armed forces are so large. They're up to the twelfth juror. I realize this is dull. Alec, but whatever you do don't act indifferent to the proceedings."

I felt the grim and passionless bulks of my two nursemaids at either shoulder. They had guns on their hips and handcuffs dangling from their belts. They conducted me to and from my cell in the county jail and for lunch to the daytime cell behind the judge's chamber. In the courtroom they were frozen beef planted behind my chair. Four walls made me feel freer than they did.

I said to George: "If I act the way I feel, I'll start chewing the table."

"That mightn't be a bad idea," George said.

County Judge Farrier leaned his gray mane toward the jury box. "Is the jury satisfactory to the defendant?"

Instantly the courtroom was silent. "The jury is satisfactory," Magee said loudly.

"Is the jury satisfactory to the People?"

"The jury is satisfactory," Hackett said.

"The jury will stand and be sworn."

THIS was it. There was a stifling hush, as before a storm. I felt the emptiness in the pit of my stomach that I used to feel when we took off on a particularly tough mission with weather conditions uncertain. Only this would be tougher than the worst of them.

The clerk droned the roll. I twisted around in my chair. Between the solidity of the guards I could see Ursula and Miriam in the front row of benches. Ursula caught my eyes and managed a wan, smiling-through-tears smile. Miriam's profile was strained and tight as she listened intently to the jurors being sworn in.

Near the rear of the room Kerry Nugent and Helen Spencer sat together. Bevis Spencer came down the aisle and whispered briefly to his sister and Kerry. "Quiet!" the bailiff at the railing gate snapped. Bevis flushed and moved on to sit beside Miriam. There were others in the room I recognized, men and women I had known half of my life. It was quite a party.

I turned back to listen to the district attorney who was rising to address the jury. He was a plump, soft-spoken man whom I would have liked under different circumstances. He told the jury that for weeks and months I had planned the murder of my wife and that only a few hours after returning to West Amber I had rushed to the bungalow and plunged a knife into her heart.

Then it was Robin Magee's turn. He had a voice that thundered and wept and sneered and whispered within a single sentence. He said that Lily had been an evil woman and that I was a decent and patriotic boy. And he sat down.

There wasn't much for the first couple of hours. The county medical examiner said that a sharp instrument, commonly known as a steak knife, was driven into the body at a point approximately three and it half inches below the left shoulderblade anteriorally and penetrated the heart to a point an inch above the apex, imbedding itself directly between the fifth and sixth ribs without emerging from the body. In his opinion, she had not been dead more than an hour when he had first seen the body at eleven o'clock the night of the murder and his post mortem at Willowby's Funeral Parlor the following day had verified the time of death. Approximately, anyway. Magee let him step down without cross-examination.

A state police lieutenant told how he and Sheriff Dowie had taken me to the county jail.

A buxom woman named Mrs. Josephs stated that she had rented the bungalow to Mrs. Lily Linn on July 5th. The bungalow had come completely furnished, including a set of six steak knives, of which Exhibit A was one.

A sergeant from the State Bureau of Criminal Investigation testified that the only fingerprints on Exhibit A were mine.

ROBIN MAGEE rose to cross-examine for the first time. Languidly he sauntered to the witness stand; almost I expected him to suppress a yawn. He must have seen a great criminal lawyer act like that in a movie.

"Tell me, Sergeant," he drawled, "did you test the five other steak knives in the kitchen for fingerprints?"

"Yes, sir, I did."

"Why?"

"It's routine. You can never tell what'll be important, so we dust everything in the place."

"Laudable diligence, I'm sure. Did you find fingerprints on the five steak knives in the kitchen drawer?"

"Well, on one was a smear of Mrs. Linn's right thumb and on another a pretty good impression of—"

"No prints on the other three knives?"

"No, sir. Washing them had removed the prints."

"Wouldn't whoever dried the knives have replaced prints on them?"

"It depends on how they're dried. Most women hold a few pieces of cutlery in a towel and take one end of the towel and dry them like that. Then they drop the cutlery into the drawer without having touched it except with the towel."

"In short, there were probably no prints on the murder knife when the murderer removed it from the drawer?"

"Probably not. But as soon as he took the knife out of the drawer he put his prints on it."

"But not if he wore gloves," Magee said. "In that case the knife could have been plunged into Mrs. Linn's heart without fingerprints appearing on it until the defendant, Alexander Linn, entered and touched the knife."

"If he wore gloves, I guess so."

"One more question, Sergeant. Could fingerprints have been wiped from the knife-handle while it protruded from Mrs. Linn's breast?"

The silence in the courtroom deepened.

"You mean," the sergeant said slowly, "take a rag or a handkerchief and wipe the prints off the knife-handle without removing the knife from the body?"

"Exactly."

"I don't see why not," the sergeant said.

Magee strolled back to our table.

"That's the way it happened," I told him excitedly. "The murderer either wore gloves or wiped off the prints after he killed her."

Magee shrugged. "At best it's a negative point, but it helps confuse the jury."