Help via Ko-Fi

On The Brink of 2000

By Garret Smith

A Complete Novelet

CHAPTER I

LOST—TWENTY MILLION DOLLARS

"SO, I've lost twenty million dollars! Tom Priestley a pauper! Good Lord! Here, for thirty years I've wallowed in wealth. and at midnight I shall be worth just exactly nothing at all!"

The young millionaire dropped the note he had just read, and threw his tall, well-knit figure into the big upholstered chair in which he had been reclining luxuriously a moment before with n0 thought of ever sitting on any other kind of furniture.

Now he lay limp, like a man who had been counted out of the prize ring. His friend, Bob Slade, stared at him in amazement from the other side of the library table.

Fur a full minute Tum offered no further explanation of his remarkable statement, and Slade was too delicate to break in upon his mood.

"What in Heaven's name can I do with myself?" he went on at length, seeming to forget his friend's presence, and addressing his remarks to the ceiling. "I can't earn enough money to buy my neckties. Never earned a cent in my life. If only old Grandfather Priestley had cut us off at once and given my father a chance to educate me to something useful, it wouldn't be so bad."

Priestley then realized he was talking to himself, and turned to his friend.

"Bobby, old boy, yours truly is up against it for fair. Well, no Priestley ever cried when he was downed, even if they have lacked practice in real difficulties for two pampered generations."

Slade rose and came over to his friend's chair. He was a short, fair, studious-looking man, the direct contrast of his friend Priestley.

It was a singular providence that in this moment of unexpected calamity Tom should have with him the only man who ever to any extent shared his confidences.

"What is it, old fellow?" asked Slade. "Are you joking? Certainly you haven't been losing money at any such rate? Tell me, if you care to. If not, I'll understand."

Priestley picked up the letter from the floor. It was from a well-known law firm on the two hundred and tenth floor of the new Cosmopolitan Building.

"Read that," he said, handing it to his friend. It ran:

Mr. Thomas Priestley,

Suite 691. Floor 65..

New Waldorf, City.My Dear Mr. Priestley:

It is my painful duty to break some serious news to you at once.

I have learned today that Maurice Fairweather, oldest son of your Aunt Jane, did not die, as supposed, but later married and has three surviving heirs: Horace Fairweather, of Chicago; Mrs. Samuel Foy, of Bridleville, Ohio; and George Fairweather, who, when last heard from, was working as surveyor on the new route of Intercontinental Monorail Company.

Of course, it goes without saying that at this hour it is impossible to communicate with all three of these persons, and, as a consequence. by the terms of your grandfather's singular will, your fortune will revert at midnight to the United States Government. Believe me. aside from all professional connections, you have my heartfelt sympathy.

Sincerely,

Warner Van Dusen.Dec. 31. 1999.

"Let me give you a little family history." said Priestley, after Slade had read the letter. "I have told even you very little about it. You see, my grandfather, old Andrew Priestley, was one of the self-made millionaires.

"The war on predatory wealth grew so hot in the last half of the twentieth century that the old gentleman turned pessimistic, and predicted by the end of the century all our private property would be confiscated, anyhow, and came near giving it away on the spot. He compromised, however.

"He decided that if by now our estates weren't absorbed, they should be given voluntarily to the government to use in promoting industrial colonies for the poor. unless all his descendants should agree to turn over the entire fortune and its income to my father's oldest male descendant—myself, as it happens. He feared, you see. that by this time the old methods of increasing fortunes would be done away with, and that if the estate were subdivided from generation to generation it would at last disappear altogether.

"So he provided that, if personal fortunes were still allowed by law, the Priestley name and prestige would be preserved if the living members of the family so wished. Hence, the will left ample incomes to the other heirs and their heirs until the end of the century, and the principal of the estate to my father and his oldest male heir in each successive generation.

"Now, as the century drew to a close, we hustled around and got all the heirs to sign away their claim to me, which they did when they found the will could not be broken. And I made it right with them by deeding them ample livings. My grandfather's fears of confiscation weren't realized, and I was prepared to enjoy an untrammeled fortune, and perhaps increase it enough so that I could treat the other heirs even better than I have and still preserve the dignity of the Priestley name. Now, at the last minute, bob up three heirs whose existence was before unknown. Hence, exit the Priestley fortune."

SLADE'S hand rested on his friend's shoulder in silent sympathy. There was a true bond of friendship between them, despite their difference of opinion and condition.

Bob Slade was a liberal of the modern type. While he believed in private property, he considered huge fortunes a curse, and had long striven with Priestley to get him to turn over his huge surplus to a cooperative industrial colony which Slade was promoting.

He now in his heart felt that the loss of wealth would be the real making of Tom Priestley, yet friendship prompted a feeling of keenest pity for the young man thus suddenly thrown on his own untried natural resources.

Yet, there was a bit of yellow in Slade. He could not help rejoicing that this fortune had gone to the common cause. And he likewise hoped now to get the popular young millionaire into his colony.

"Old man," Slade said at length, "you are now going to show the stuff that is in you. You know I sympathize with you, but what you want is counsel, not idle sympathy. You are, at the beginning of this new century, commencing to live, and the loss of this wealth has shown the way.

"Join our association, and there will be plenty of work for you to do, and a comfortable living and respectable position. The men of our colony are winning more and more respect as time goes on. We are the real answer to your grandfather's fears.

"Private fortunes and private enterprises still exist, and will exist till through cooperation, learn voluntarily to give over to the common cause what they cannot use personally. Come. I'll take you to our watch-night meeting, and you shall join us with the opening of the New Year."

The two young men were now standing, facing each other.

Priestley for some moments considered It his friend's words. Here was, indeed, a way out.

The new colony was a popular fad. Many persons of means had dedicated their property and lives to the cause.

But the tempation was brief. Suddenly, and almost roughly, he threw his friend's hand from his shoulder. The spirit of old Andrew Priestley was swelling in the heart of his grandson.

"Bob," he said, "no! You may be right. Your words are tempting. They offer me the easiest way—perhaps the right way. But I will fight it out just as old Grandfather Priestley fought his battles, and as he would fight this one.

"I despised and flaunted your socialistic colony while I had wealth. I will not creep into it now, begging for a chance. I will go out tonight and begin again at the bottom of the ladder, as my grandfather did. And, by Heaven, I'll win fame and fortune by my own old-fashioned individual efforts, as he did.

"I'll start tonight, and I'll get a flying start. This time I start right, and if I win fortune I'll use it in my own way to help humanity. Bobby, I'll do this the moment I have back in my possession, where it can't get away, twenty million dollars. I'll turn over to you one million to use as you will."

He paused a moment. There was a new fire in his eye.

"Bob," he went on, advancing, and raising his voice, "there are four hours left till midnight. No one but you and my discreet lawyers know I have lost my fortune. Much can be done, with my resources and credit, in that time. Perhaps you think I'm crazy, but something tells me that before the New Year's bells ring in old Trinity tower I shall win back every cent of that twenty million dollars. Come! There is no time to waste!"

CHAPTER II

THE EVE OF A CENTURY

BOB SLADE'S spirits fell much farther and faster than did the little private elevator in the instant of time it took the two young men to reach the lobby of the great hotel, sixty-five stories below.

He had long labored to obtain the cooperation of his dearest friend in his dearest scheme. Now, when he thought he had secured it and his friend's fortune besides, he found it farther away than ever.

As he stepped out into the brilliantly lighted moving sidewalk tunnel on the second level below the street surface, Slade paused.

Should he leave Priestley here and go to the meeting of his association, as he had planned?

Then he remembered Priestley's promise to give him personally one million dollars as soon as he had won back his twenty million.

For the moment he believed Tom's boast that he would recover his huge fortune in the four hours that remained till midnight. He decided to go with him.

"How many people are traveling about in summer clothes since this tube was opened!" remarked Tom, as they stepped from the stationary sidewalk to the first of the series of moving ones that carried them north. each running a little faster than the other. "You see, they can get the whole length of Broadway now from any of the big apartment-hotels on the island without going into the open air. Doesn't look much like the January street scenes even you and I can remember, when furs and heavy overcoats were in evidence. Those radium roof-lights are as good as sunlight. And smell that air! I swear, if you'd close your eyes so you couldn't see those polished concrete arches overhead, you'd say you were in Bermuda!"

Tom was apparently in excellent spirits. Or was it bravado? Slade could not be sure.

They crossed from one platform to another through the gaily dressed New Year's Eve throng till they reached the northbound center walk, which was provided with comfortable cross-seats and was moving at a rate of fifty miles an hour.

"I want to, see Horace Breen in the Getty Square Apartments at Four Hundred and Tenth Street," said Priestley as they sat down. "I guess if we get off at Seventy-Second Street and go down to the express-train level we'll gain time. I know Breen will be in, because he told me this afternoon he was entertaining a New Year's Eve party in his rooms this evening. You see, I happened to have a little talk about several good stocks that were down too low just now, and he urged me to buy then; but I told him I wasn't speculating. Now, I have a plan that will work miracles."

At that moment the indicator showed the approach to Seventy-Second Street, and the two stepped across the platforms into the big moving stairway. The next moment they were seated in a roomy, comfortable train that would have done justice to a trunk-line in the nineteenth century, except that it ran on a single rail, like a series of bicycles.

A soft-toned bell rang in the vestibule. An indicator in the end of the car announced the next stop. The door closed noiselessly, and without jar or racket of any sort the train was under way, and in half a minute making one hundred miles an hour.

"I was reading an old newspaper file today," remarked Slade, "in which the writer was bitterly bewailing the noise, jam, and stench of the subway fifty years ago.

"I've heard my father tell about it, too; and do you know I wonder that anybody could have been induced to live in this city in those days. What a tremendous change in a century!"

THIS soliloquy was cut short by arrival at their station. They stepped into the vestibule of one of those magnificent towers that line Broadway for forty miles up the Hudson River. They were roomy, airy winter residences, to which all the well-to-do of the Northeastern States flocked during the holidays.

An elevator took them to the seventy-third floor, where they were ushered into the presence of Horace Breen, a middle-aged broker, whose financial skill was rapidly winning him renown in Wall Street. After a few preliminary remarks, Priestley went straight to the point and proposed to his host a financial scheme that made the heart of the now eager Slade bound with confidence. He already felt that million-dollar check in his fingers. He had to remind himself, though, that the money was not for his personal comfort, but for the cause.

"Mr. Breen," said Priestley, "I don't need to talk much, for you know the scheme better than I. You said this afternoon that you could double your money day after tomorrow, if you have a few million dollars more credit. I will make it twenty million. As you perhaps know, my private fortune is rated at that figure, I'll stake my entire credit to that amount at this moment.

"Here is a list of my securities. Phone to ten different brokers right now and place with them orders of two million each on those stocks you mentioned on ten-point margins. Then you can place your own money yourself.

"As soon as the exchange opens day after tomorrow, our orders go in simultaneously. We have our stock in hand before the Street realizes what has happened. Then, with such buying, the stock will jump, and in half an hour we can sell out at double our money. Is it a bargain?"

Such a coup had not been worked since the Gormley deal forty years before. It was fresh again. The broker eyed this enthusiastic novice in finance strangely for a moment; then recovered himself, and said hastily: "To be sure, to be sure. I'll call up some people at once. Excuse me while I telephone."

In half an hour the broker returned.

"It is all right," he said. "Now, as a? matter of form, you will have to sign these papers to conform to the new law. You see up to now, any one known to be worth twenty million dollars could get credit for that amount in a stock deal with brokers who knew him. On a quick change like this he could buy margins for that amount and not hand over any money till after the deal was closed. You, I think, expected to do that. But I suppose-we were getting too free; there was danger of another Gormley deal.

"The new anti-stock gambling law goes into effect tonight, and it requires that a man sign a bond, certifying that he owns, free of encumbrance, in his own right property of some sort equal to the full amount of his stock transaction before he can buy any stock at all.

"Now, of course, I know you are all right, you understand, but we will have to conform to the statute our blessed meddling reformers have foisted upon us. You see, the good old days of real stock gambling pass at midnight tonight. But we can work one final coup and clean up some fortunes from the wreck if you have twenty million of loose securities actually to put up."

Priestley took the bond and drew out his stylograph in a daze.

"You mean," he stammered, "that—that I must certify under penalty of imprisonment for false statement, that at the time of my transaction I am actually worth twenty million dollars? This transaction won't actually take place till after New Year's Day."

"Exactly," said Breen. "That should not trouble the grandson of Andrew Priestley."

The broker laughed pleasantly, then checked himself as he observed the strange look on the young man's face. For some moments neither spoke. The silence grew decidedly embarrassing. At length Tom rose and put down the bond.

"I am sorry, Mr. Breen," he said, "but I'll have to change my mind. A reason—has—has—just occurred to me why I should not undertake this deal, after all."

Breen stared at Priestley in amazement. "So this is the way you do business, is it?" he said coldly. "You have got me into a nice compromising position, haven't you? I think an explanation is due me."

Priestley rose falteringly.

"Mr. Breen," he said, "I can only explain this much. There is a provision in my grandfather's will so tying up my fortune that I cannot sign any such bond as this. I was unaware of the law when I came to you."

"We had better not talk any further," replied the broker coldly. "I am accustomed to do business with men who understand what they are doing."

The next moment the two young men were in the open street.

"I want to walk and think," was Tom's explanation as they stopped at the street-level landing.

For three blocks they walked through the merry throng of revelers, Priestley oblivious of all around him. Finally he stopped and faced Slade.

"I guess it's the bottom of the ladder and the pick and shovel for me, after all." he said. "The dawn of this blessed new century has swept away even my credit!"

CHAPTER III

ANOTHER CHANCE GONE

AT that moment two men emerged from the Subway exit. The younger of them caught sight of Priestley and clapped him on the shoulder.

"Hallo, old man!" he shouted. "Great luck, catching you. I have some important remarks to make. Good night and Happy New Year to you," he added to his companion of the subway, an elderly gentleman, who was evidently a little the worse for New Year's Eve cheer.

"I've been trying to get rid of old Holden all the way up. He has a melancholy drunk," went on the young man, as the older man, after staring stupidly at the group for a moment, walked away. "I took him down to hear Trinity chimes just to humor him, knowing they wouldn't ring for four hours, and thinking he'd get tired of waiting, as he did. He was sore because they didn't crowd the streets and make a hideous racket as they used to New Year's Eve when he was a boy.

"He bought a horn, in spite of all I could do, and blew it till a cop took it away from him. Then he decided to come uptown, and all the way he speculated on the great loss to the country that will be occasioned tomorrow when they have to change the first two figures of the standing dates on all their stationery from 19—to 20—. He'll get home all right now."

"This is Mr. Wrenn, Bob—Frederick Wrenn," said Tom, introducing Slade. "Mr. Wrenn, Mr. Slade."

"I have heard of Mr. Slade," rejoined Wrenn pleasantly. "He is known both as a radical and a friend of yours. But here is what I am after, and I think Mr. Slade will enjoy the experience, too. We have a novel New Year's Eve in store for us, if you have nothing better, and incidentally, Tommy, there is an opportunity for you to invest some money at a big profit.

"Old Professor Rufus Fleckner, whom I have the honor of knowing, has made another invention, the greatest yet. He is going to give the first exhibition tonight to a few friends. He invited me, and said I might bring a couple of pals. I tried to find you this afternoon.

"Mr. Fleckner needs some capital to put this thing on the market. He needs a lot, and there is a chance to double an investment. I suggested you as a possibility, and he was impressed with what I told him about you. Can you come along? It is just about time. He was going to begin at nine o'clock. He lives just around the corner, and we can make it in a minute."

"I'll go," said Priestley without hesitation. There was a renewed fire in his eye and a return of the hope he had lost while interviewing Breen. "Come, Bob."

Indeed, the name of Professor Fleckner was one to conjure with. Several huge fortunes had been made by the backers of this wizard's inventions.

He was no idle visionary. The successor of Thomas A. Edison of the previous century, he accomplished marvels of which the earlier inventor had never dreamed. He it was who perfected television which transmitted the voice and image around the world without intermediate stations, and made it impossible for any other receiver to cut in on the message except the one intended.

His method of extracting electrical power directly from the atmosphere had forever done away with the need of coal and relegated waterpower to the limbo of historic curiosities. His greatest service to mankind had been the enforcing of universal peace, by the invention of the violet-ray destroyer, with which one man could press a button and annihilate an army.

Hence, when Priestley learned that Fleckner had another invention ready to place on the market, he knew that the man in on the ground floor with capital would reap millions of profit in a short time.

There were still three hours left during which he was a full-fledged millionaire. Instantly a plan flashed through his mind.

The next moment they entered the wizard's apartments in the tower of one of the highest buildings on Yonker's Heights. Slade and Priestley were alone for a moment in the coat-room.

"Don't worry, old man," said the latter, "I won't get caught this time. If this invention is all right, as of course it must be, I'll know it in half an hour. All I've got to do is call up a few of my millionaire friends, tell them I am financing something of Fleckner's, promise each a bonus in Fleckner's stock and security for a loan in bonds I hold, and I can nail down to my own name the lion's share in the company. The old man's not a close financier and won't probe me too closely. I will play square with him, too."

As they entered the inventor's laboratory, where a dozen men were gathered, the professor was just beginning an formal lecture.

"I am about to revolutionize society, and all its present organization," were first words the newcomers heard. "You all know what I have done with television, he went on. "I have followed up those experiments till I have perfected an apparatus which truly makes distance a thing of the past!"

These remarkable words roused Priestley from his unpleasant reverie.

He realized that the little audience in the laboratory had subsided into a breathless, awed silence.

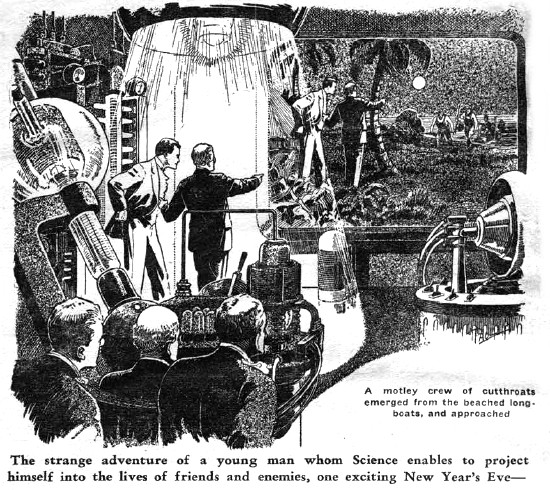

PROFESSOR FLECKNER stood in front of what appeared to be a giant television screen, surrounded by complicated electrical machinery. His piercing eyes fixed on those before him with an influence almost hypnotic. For a full minute after uttering his amazing statement, the wizard stood in impressive silence.

"You before me are about to take part in the most remarkable watch-night the world has even seen," he went on at length. "From this evening the wonders of the 'Arabian Nights' will be trivial, commonplace. I stand at the entrance to a new century, and with the magic wand of science I tear away the veil that has hitherto kept nations apart and retarded human progress—the dense veil of distance."

The speaker paused a moment, then added with still greater emphasis:

"I have made travel a thing of the past!"

There was now a little hum of excitement around the room; from some, exclamations of wonder; from others, murmurs of doubt. Priestley sat drinking in the inventor's every word, in his face the rapt look of reviving hope.

"To prove my claim is not idle speculation or a figure of speech," Professor Fleckner continued. "I am going to permit you tonight to take part in New Year's watch-meetings in every portion of the world, and that without leaving this room. Time will come when with this instrument I will penetrate the baffling mysteries of the starry planets. That would be only another slight step. But for the present, my currents will act successfully only in the atmospheric envelope of the earth."

As the professor finished speaking, he switched on the power. The screen before them seemed to melt away; and suddenly the gathering found themselves looking at the street at the base of the great building in which they were all seated.

A little newsboy, apparently only a few feet from them, was haggling with another over some change. Every word came to them clearly, as over a radio.

One of the gentlemen stepped out on the balcony and looked over. Several others followed. There, so far below that they seemed like mannikins, were the two newsboys. The hum of the crowds came up.

The professor moved a controlling lever and the room in which they were sitting seemed to glide along the curb, Far up the street the watchers from the balcony could see the portals of one of the biggest hotels on Yonkers Heights. In a moment, as they looked back into the room at the screen, they seemed to be standing directly in front of those very portals. A young lady and gentleman stood a little at one side of the entrance, supposedly in a confidential conversation; but to the amusement of the onlookers, every word was as though spoken clearly in their ears.

"But, professor," said one of the party, stepping back inside, "how is it done? There certainly is no transmitting station at the other end as there is in an ordinary television circuit."

"This instrument acts like a searchlight," replied the professor laughing triumphantly. "A searchlight that both sees and hears and shines through opaque walls and is absolutely unaffected by distance! By a swing of this controller I can send this searchray to any point on the face of the earth and bring that point instantly on the screen.

"The transmitter and receiver are both in this building. You can see part of the mechanism on the roof."

From the balcony to which he led them, he pointed out a huge network on the roof. Priestley and Slade were unable to follow the technical explanation which the professor then gave.

As they entered the laboratory again, Wrenn introduced his friend, and Priestley, anxious to save his remaining precious time, poured out at once his confidence in the new invention and his willingness to finance the company. He took care not to suggest that he would have to borrow money to do so.

The inventor listened patiently. There was on his face the look that one would give a child who was laboring under a delusion.

"I am sorry, Mr. Priestley," he said, when Tom had finished. "I thought I could use you when your friend Wrenn suggested it. I went to see your attorneys about it this afternoon, understanding that they managed your estate for you. Mr. Van Dusen, head of the firm, is an old friend of mine and perhaps told me more than he should about your affairs. I wouldn't mention it now, were it not for your extraordinary offer. Perhaps, though, you did not get the letter he was sending you when I was there. I understand, that owing to complications connected with your grandfathers will, your estate is in no shape to invest in anything. I am glad to have met you, however, and I hope you will get on your feet again."

He turned again to his instrument.

Tom Priestley sank into a chair, lost in despairing thought.

CHAPTER IV

DISTANCE ANNIHILATED

"LET us try an opaque wall," said the professor. "Take this field-glass and examine the windows of that Yonkers hotel. Pick out one with a light in it so that you can identify it, and then look at the screen."

The field-glass was passed around the balcony and after a little the company agreed on a window and indicated it to the professor. Through the glasses the company could catch, through half-drawn curtains, faint glimpses of a company within.

Turning to the screen, they gave a start of surprise to find that they had suddenly been hitched onto the apartment in question, and were listening to some merry banter around a little group of young people holding a New Year's Eve party. The wonderful ray had not only practically transported them a half mile up the street but had faced them about so they were actually on the screen looking across the strange apartment and out of the window that they faced.

"I am independent of direction also," said the professor, turning the controller.

In an instant the strange apartment was reversed on the screen, and they were facing persons who had their backs to them a moment before. Another turn of the controller and the room seemed to spin around like a top.

"You see," said the professor, "I have done away with the need of a transmitting station at the other end of the line, the thing that has hitherto limited the use of television."

Then the bewildered audience for the next few minutes entered, uninvited and unseen guests, company after company of New Year's revelers. Suddenly the company found themselves facing an unfamiliar street. It was in a big city and was likewise filled with holiday celebraters, but no New Yorker recognized it.

"Michigan Avenue, Chicago," shouted a gentlemen suddenly. "My own home is a block away. Let me see how the servants are behaving. They've been alone in the house for a week. It's No. 681."

At the word, the street slid along the screen and stopped when a handsome marble portico in the middle of the screen bore on its surface the number 681. Then the door seemed to shift toward them and suddenly melt away, and the watchers in the laboratory found themselves moving through a huge, old-fashioned hall, of the style that came into vogue about the middle of the twentieth century.

At the farther end, another door faded away, and as the room beyond the screen the watchers heard distant sounds as of wild revelry. The householder stirred uneasily. Through two more rooms they passed, then the sounds came from below.

A shift of the professor's controlling lever, and they dropped through the floor and were in the midst of a wild scene.

It was the servant's hall, holding some twenty young men and women, some of whom the Chicago man recognized as his own servant, and all much the worse for liberal use of his own rare old wine.

The girls of the party were decked out in rich finery of a style and taste hardly within reach of the servant class. So perfect was the work of Professor Fleckner's machine that the shouting and singing of the revelers seemed to be in the laboratory, and the watchers who sought to comment to each other on the scene before them could not make themselves heard.

The Chicago man was beside himself. He rushed up to the screen, as though he thought for a moment he could rush on the scene and stop the despoiling of his winecellar.

At length, in a temporary lull in the racket, he shouted to the inventor.

"Can't this business he stopped in some way? Can we telephone the Chicago police from here? They are drinking up all my old wine, and those girls have on my wife's best dresses and those drunken fools will set the house afire. It's an old-fashioned building, and not perfectly fireproof. Tell me where the phone booth is, please, and I'll call the police and send them around there. I'll take the next monorail for Chicago."

The professor switched off the noisy crew for a moment so that he could talk to the excited man.

"Hold on, my friend," he said. "I can fix things without any trouble. I will show you another and still more wonderful phase of this invention that I had intended to bring out in another way. But as long as we stumbled onto this impromptu party, I might as well have you attend it in person as well as in the role of an invisible spectator."

Fleckner turned then to his switchboard, tightened up a few screws and threw over two switches.

"Now," he said, "when the machine goes to work again, every one in front of this screen will be projected out like a perfect life-size mirage at the end of this ray. In other words, this gentleman here can, to all appearance, stand in the midst of his reveling servants, and address them face to face as though he had dropped from the ceiling."

His listeners gasped in astonishment. They would have to see this demonstrated before they would believe it unreservedly.

"Now, if you, Mr. Chicago Man, and you and you and you," the inventor went on, pointing to three others of the most husky men in the company, "will just stand in front of this screen, and be ready to act just as though you were in that room, we will give these people a scare that will sober them in a hurry and stop this watch-night performance some time before the glad New Year dawns."

The men did as requested. The professor threw on another switch. To the astonished eyes of the company the room in Chicago this time seemed to stand out from the screen and embrace the men in front of it, who, to all appearances, were now a part of the company of revelers.

TO the startled four thus transported the miracle was all the more realistic. Their companions in the laboratory seemed to have been blotted out, and they found themselves face to face with the drunken servants.

Suddenly there was a silence among the merry crowd. Some one had seen the unexpected guests. One servant recognized the master. Every one was speechless.

Then the householder recovered from his own surprise at this sudden shift, and found his voice.

"So this is the way I can trust you people, is it?" he demanded in thunderous tones that were evidently heard by the servants, for they visibly winced. "You people who don't belong here go out that door to the street, and if there is one of you in this precinct five minutes from now you will be sent up for burglary, for I am going to phone the police at once.

"The rest of you go to your rooms, take off the clothes that don't belong to you, pack your own belongings, and go also. Don't let that take more than five minutes, either. Don't let me ever see any of you again."

The revelers rose as one very sobered man, and in less than five minutes the directions of the householder had been obeyed.

The figure of the latter, directed by the professor's skillful manipulations, followed the butler about to the last, and saw that he had locked all the doors. The only slip in the realism came when the man surrendered the keys to his master and they fell right through a shadow hand and jingled on the stones of the areaway.

The butler was too troubled, however, to notice it was anything more than a bit of carelessness, and the next minute had slunk away. Then the professor turned off the ray, and the four found themselves back in the laboratory, standing in front of the screen.

As this little byplay closed, Tom Priestley rushed to the front of the room in intense excitement. He had been watching proceedings with growing interest.

When Chicago was thrown on the screen, he suddenly remembered that one of those three cousins he had so desired to see, that they might sign his fortune back to him, lived in Chicago. Then he had watched the astonishing demonstration of transference that followed with a sudden resolution.

As it closed he looked at his watch. It lacked still two hours of midnight. Why could he not be transported in figure to Chicago, hunt up his cousin, and get his signature?

"Professor Fleckner," he shouted to the startled inventor as he rushed to the front of the room in a frenzy. He forgot, for the time being, the presence of the rest of the company. "Could I, by this means, go to a man in Chicago and get him to sign a paper that would hold in law?" he demanded.

"Certainly, Mr. Priestley," was the reply. "It can be witnessed at this end also by Mr. Brewster, whom you have met this evening, and who is a notary public. This instrument will at the same time reproduce here an exact copy of the document with notary's signature.

"That involves no new principle. We have had the chirotelegraph in practical use for fifty years, you know. One of the first legal decisions after business men began to sign checks by wire in New York and have them reproduced by the instrument in Chicago, was that, when properly witnessed, the reproduction of a signature by that means was the same in law as the original writing under the writer's hand. In fact, that it was an original. So any paper signed tonight in Chicago and reproduced at that instant by my instrument and witnessed here by a notary would be legal. Am I not right, Mr. Brewster?" he added, appealing to the lawyer he had just mentioned.

"Perfectly right, professor," was the reply.

"Professor Fleckner," went on Priestley excitedly, "you offer me a forlorn hope. As perhaps you know, from your conversation with my counsel today, my fortune reverts to the government at midnight unless I can before then get three remaining relatives to sign away their claim under my grandfather's will. I have just two hours left. If you will save that fortune for me, I will not merely invest in your company to float this wonderful invention, but I will give to you personally one million dollars, and think it a cheap price!"

CHAPTER V

A CHASE FOR TWENTY MILLION

FOR a moment there was dead silence in the little room. Then followed a hum of excitement. Every one there the heir of the Priestley millions, by reputation at least. Though not as rich as some of the young multimillionaires, he was recognized as one of the leaders of the smart set and a representative of that element of established wealth too firmly entrenched to be disturbed by the class war so long brewing.

Now, to learn from his own lips that this great fortune was to disappear in a night, and disappear to further the very cause of which the Priestleys had been such conspicuous opponents, this was indeed theme for excitement.

While this little buzz of gossip was going on in the room, Tom was explaining to the professor in low tones the details of his grandfather's will and the information he had just received regarding his unknown cousins. The company quieted down again, after a moment, and watched eagerly for the next move in this extraordinary New Year's Eve game.

"We have just two hours to midnight," the inventor said at last. "In that time we must locate three unknown people who may be scattered anywhere over the face of the earth. First, we must see Mr. Warner Van Dusen, attorney for Mr. Priestley, and learn if he has any further information regarding these missing heirs. I will ask you all to watch intently and be ready to act as witnesses of all that follows. Close watching will be needed, as we must move quickly. There is no time to lose."

The professor turned on the magic ray and began the most remarkable search the world had ever known. What follows this point in our story takes much more time to tell that it did for the actual occurence.

Bear in mind that distance had been annihilated, and the actors in this unique drama were transported from scene to scene instantly. The mere telling of those moves in the fewest possible words requires time.

The scene on the screen now was the library of Mr. Warner Van Dusen. Tom had been there many times on business connected with his estate, and recognized it at once.

Reading by the table sat Mr. Van Dusen himself. The company in the laboratory were as yet invisible, for the professor had not turned on the projector.

"I thought I would find him in and alone," remarked the inventor. "He is an old bachelor, and seldom mingles in society, even on New Year's Eve. I have told him of my invention, but he hasn't seen a demonstration as yet, so I won't startle him too much."

The professor knocked on the table beside him, and the sound was reproduced in the apartment on the screen.

"Come in," said the lawyer, supposing it a knock on his own door.

The professor turned on the projector, and spoke from just without the lawyer's door.

"This is Professor Fleckner," he said. "Don't be startled. I am not here in person, but am projecting my image so that I can have a talk with you."

Then the professor and Priestley, whom he had called to his side, stepped through the closed door into the presence of the lawyer, who, despite his warning, nearly fell off his chair in surprise.

"Mr. Van Dusen," began the professor, without waiting for the lawyer to recover his equanimity, "I am going to save the fortune of this young gentleman before midnight by means of this invention, if you will give us some more details as to the whereabouts of those missing heirs. We have no time to lose."

"Fleckner, you are going to give me heart-disease some day," said Van Dusen. "Well, as to those heirs, let me see. I followed the case closely, and can tell you from memory all our meager data that counts.

"We only learned of them today, through a friend of that branch of the family. Two years ago, Horace Fairweather, a worthless sort of specimen, I fear, lived with his wife at No. 901 Dearborn Street, Chicago. May not be there now. Mrs. Foy, a widow, moved to Bridleville, a little town in southern Ohio, ten years ago. Informant hadn't heard from her since.

"George Fairweather a soldier of fortune, was an engineer surveying for the Monorail on the Rocky Mountain section three years ago, but lost his job and disappeared. That's all I—"

"Thanks! Goodby!" snapped the inventor, and without further formalities faded from the astonished lawyer's sight.

That same instant the company found itself apparently out on a strange street. "Dearborn Street," whispered the Chicago man.

RAPIDLY the house-fronts slid by on the screen till on a tenement-door they saw the number 901. The professor and Priestley were so focused that their images were projected on the scenes explored by the wonderful ray. The controlling switchboard was just outside the range of vision. The rest of the company were visible spectators.

The two men, in image, entered the hallway of No. 901 and examined the nameplates. No name like Fairweather appeared. Priestley's heart sank.

Then that surprised organ jumped, as its owner found himself apparently standing in the areaway below, and the professor's blows on the table at his elbow seemed to be delivered on the dingy door that was projected on the screen.

In a moment they heard a shuffling step, and the door opened. A man appeared, evidently the janitor.

"Does any one by the name of Horace Fairweather live here?" asked Fleckner. "Or did any such person ever live here?"

"Never heard of him!' snapped the janitor, and slammed the door.

"Cheer up," said the professor. "We'll interview the other tenants."

Instantly they were in front of the first apartment. A rap brought an ill-favored woman to the door. She had never heard of Fairweather. So it went, all the way up the building.

At length, as they were about to turn in despair from the last flat, where a garrulous man in tattered coat was trying vainly to recall who held his flat before him, the fellow suddenly brightened up and exclaimed:

"Why, yes! Fairweather, you say? That was the name. Jake Shultz, what keeps the saloon on the next corner below, righthand side, told me the other day he had seen that man. He—"

"Thanks!" came instantly from the professor, whereupon he and Priestley found themselves outside, and Dearborn Street was flashing by again. What kind of an impression this sudden vanishing made on their informant of the flat they had no means of knowing.

While Tom was speculating on the possibility of reading next morning about several sudden deaths from fright in Chicago, he found himself and the professor standing in front of a bar presided over by a porcine-looking German. The man was plainly startled, and those around the bar near them were staring at the intruders with hostile looks.

"Say, you," said the proprietor, glowering at them, "pe you fellers gum-shoes? I titn't hear you come in yet. Vy you schnooping round so sthill?"

"Fly cops!" growled a man at the professor's elbow. "We never seen nor heard 'em come in, did we, boys?"

"No!" came an unfriendly chorus.

The professor looked a bit helpless.

Then Priestley jumped into the breach with his superior worldly knowledge. He pulled a ten-dollar bill from his pocket with a wink at the professor.

"Drinks all around," he said. "We simply came to ask Mr. Schultz after a man we used to know."

The crowd visibly mellowed, but the hostile look was not altogether dissipated. Three of the ugliest-looking customers in the crowd had edged around between the visitors and the door. Priestley smiled when he thought of the surprise to follow when the professor and himself were ready to remove their images.

The old saloonkeeper glanced at the bill in Tom's hand, and at length turned to draw the drinks, first casting a meaning look around the company of his regular customers.

"What we want to know," whispered Tom confidentially to the saloon-keeper "is where we can find Horace Fairweather, who used to live at No. 901, top floor."

The others had crowded in closely, and despite Tom's precautions, overheard his request.

"Fly cops!" again came the murmur from the crowd. "Kill 'em!"

Tom, amused at the futility of such a suggestion, turned a smiling, fearless fact on the angry company.

That enraged them the more.

"Kill 'em!" came the cry again. "Look out fer guns!"

"Wait!" roared a big, ugly man, waving the others back. "What ye want o' Fair weather?" he demanded.

"Are you Horace Fairweather?" asked Tom hopefully.

"I?" roared the stranger, brandishing a big fist in Tom's face. "Do I look like a pale, one-eyed runt of a second-story man?"

The man's anger was so evident that Tom took this description to be a real characterization of his beloved cousin.

"Kill 'em!" again came the cry.

A man at Tom's elbow aimed a blow at the young man's head that would have floored Priestley in the flesh. As it was, Tom instinctively dodged.

The fellow's fist shot, impotent, through the image of Tom's head, and the deliverer of the blow nearly lost his balance. He staggered over against the bar and looked at the smiling young man in amazement.

"Talk about dodging," he panted. "Slick, ain't ye?"

At that instant another thug swung one of the heavy café chairs over his head and brought it down on the image of Professor Fleckner. It went through that apparently solid body and crashed to the floor.

At the same time the professor, taken by surprise, also dodged, and in doing so stepped out of the range of his projector. To the thunderstruck onlookers he seemed to fade away in thin air.

The crowd staggered back, paralyzed with astonishment. Among them stood Tom, smiling and serene. An inspiration seized him.

"You thought you were dealing with ordinary men, didn't you?" he sneered. "You can no more hurt us than you can the winds of heaven. Now," he added fiercely, turning to the man who so vehemently denied being Horace Fairweather, "if you know when you are well off, tell me what I want to know about Fairweather, and tell me quick."

The trembling wretch twice opened his mouth to speak, but his breath each time failed him. Then the door opened behind them, and a harmless, unsuspecting seeker of liquid refreshment entered.

That broke the spell. The way was clear to the crowded street. With a howl, the man nearest the door bolted through it. The others followed. The next moment the image of Tom Priestley stood alone in the deserted bar.

CHAPTER VI

A TRAIL OF CRIME

IN the excitement of this bizarre adventure, Torn for the moment forgot his real quest. He was brought to his senses by the voice of the professor.

"We must follow that man," said the inventor, "and force him to explain his clue."

As he spoke, he turned the street on the screen and worked it rapidly back and forth before them. For some minutes they searched but nowhere could they discover the big man who had admitted knowing Horace Fairweather. He had sought shelter in one of the other dives in his panic of fear, and in that beehive section they might search for him an hour in vain, even with the facility afforded by the wonderful ray.

For five minutes the inventor worked his controlling switch rapidly. Suddenly the Chicago man jumped up and rushed to the professor's side.

"By jove!" he cried, "I believe I saw Fairweather, if that fellow's description was accurate. There was one little pale-faced chap with only one eye in the crowd punishing my wine. He didn't seem as drunk as the rest, and was the first to sneak away. Of course, it's only a chance; but we might find him in that neighborhood still. He has only had fifteen minutes to get away in."

"We'll try it as a forlorn hope," decided the professor instantly.

For the next few minutes he worked rapidly, passing in panorama all the sections of street about the Michigan Avenue house where the servants had been holding revel, examining the face of every person. Every car leading away from the scene was also scrutinized.

Nowhere, however, could they sight a small, pale, one-eyed man. Again the professor swept the scene, going through street after street. All in vain. Precious time had passed.

Professor Fleckner turned off the ray for a moment and heaved a sigh of despair. He was thinking of that million-dollar reward.

"I'm afraid it's no use," he muttered. "Only an hour and a half left, and none of the three found."

Priestley sank to his chair, resigned to his fate.

"Would you mind looking at my house again," asked the Chicago man, "as long as you've given this other thing up? I'm worried a little about it, especially as I left those keys in the areaway."

"Go ahead," said Tom, in answer to an inquiring look from the inventor. "Don't mind me any more. There's nothing to be done."

Professor Fleckner turned on the ray once more, this time without the projector; and a moment later they were looking at the areaway of the Chicago man's house. Minutely they examined the tilings. The bunch of keys had disappeared.

The houseowner jumped to his feet with a cry of distress.

"They've come back and broken in!" he exclaimed. "Quick! Stop them!"

Instantly the interior of the house was thrown on the screen and passed rapidly before the watchers, room by room. On the second floor, in front of a closed door, crouched two figures, one holding a dark lantern.

In one could be recognized the butler whom the company had seen so summarily dismissed less than half an hour before. He was holding the lantern and directing his companion, who was working at the keyhole with a skeleton-key.

"Sure, he always sleeps in this room," the butler was saying. "Don't you bungle the job. Put him out o' business so thorough he'll never discharge no more butlers. We'll get enough out o' here, too, so I'll never huttle for anybody again. I'll 'ave that little bar in a month from now. Wot a fool I was to work honest for that man all these years!"

"Be still, you drunken fool!" ordered the man at the keyhole.

Priestley caught one look at this fellow's face and jumped to his feet, exultant.

It was the thin, one-eyed man. They had caught their quarry unexpectedly.

The professor left the instrument for an instant, stepping into the next room. He returned with two pairs of heavy magazine pistols.

Giving two to Tom, who was nearest, and taking two himself, he put Priestley in position at one side of the crouching figures on the screen and took up a place on the other side himself.

"Be ready to act as though you were on the spot," he directed. "I'll turn on the projector, and we'll get them."

"Just a moment, professor," said Mr. Brewster, the lawyer, coming forward.

"This man with the key is evidently the Horace Fairweather you want. Let me warn you now that any signature you get from him through fright or threat will be worthless. So be very diplomatic. If it weren't for the necessary speed, I would advise waiting till you could see him under circumstances not so compromising.

"Here's an idea! Why not make a noise in another part of the house and scare them out? Then, a moment later, you can meet them on the street, and there will be no appearance of knowing anything that will make this man act without his free will."

The professor saw the point. He and Priestley stepped back again. Fleckner moved to the other side of the laboratory and made on the rug the sound of a heavy, muffled tread. The two figures in the Chicago house, over a thousand miles away, sprang to their feet in alarm.

"Some one downstairs!" whispered the butler in terror.

"This way," replied the other. "The fire-escape is in the rear, and we can get through to the other street."

The professor's search-ray followed the men to the back of the house, down the fire-escape, over the fence to the next street, where the two crouched behind a low wall and waited till the policeman, who was passing at the moment, should get safely by.

"We'll make sure of catching these scoundrels after we get what we want," said the professor. "Put your pistols in your pockets but be ready to draw them," he added to Tom, who obeyed, the professor setting the example.

Then the latter turned on the projector, and the images of himself and Tom appeared on the sidewalk a little way behind the officer.

Moving swiftly to his side, the professor accosted him. The policeman stopped, startled.

"Ah, pardon me, gentlemen!" he exclaimed, "you came up so quietly I was taken back for a second."

"We have our eye on some men you want," the professor explained. "They are behind the wall two doors below, waiting for you to pass. We found them robbing a house over in the avenue. Now, we particularly wish to see one of them, whom we know, before you alarm him, because by a strange coincidence he is a relative of this gentleman, who wants him to sign some papers before there is any appearonce of compulsion. We'll explain more fully afterward. All we ask now is that you stand by and see that there is no foul play, and arrest the man after we are through with him."

"This is indeed strange business, gentlemen," said the officer suspiciously. "Who is this relative of yours, sir?"

"His name is Horace Fairweather," replied Tom. "He—"

"Horace Fairweather!" exclaimed the officer, alive with excitement, "Not Bruiser Horace! A big, black-complexioned brute, with a scar across his forehead? We've been after him for months!"

CHAPTER VII

A GRIM ALLY

NOW, it was the turn of the others to be excited, and at the same time crestfallen.

Tom and the professor looked at each other in dismay. This was the exact description of the man they had seen in the saloon who had so vehemently denied being Fairweather. He had eluded them by a clever trick.

"No," said Tom at last, "I guess we are on the wrong track. The man we thought was Fairweather is a little, pale fellow with one eye."

"Sneaker Tim!" exclaimed the policeman. "A catch almost as good. He's a pal of Horace's; and if we catch him, maybe we can worm out the whereabouts of the other."

"Here!" exclaimed Tom excitedly. "We know a roundabout way to get behind these fellows through these premises. You walk along as though nothing had happened. When you are opposite the third gateway from here we'll be behind the 'wall with our pistols to the backs of the men you want. We'll whistle, you shove your pistol right over the wall, and we'll have our birds cornered."

This extraordinary affair plainly nonplused the officer. He hesitated a moment only, however. Tom's determined tone had its effect.

"As a rule, I'd say you people were crooks trying a new game on me," he remarked frankly with a laugh, "but you look too honest, and, anyhow, I'll try and see what the game is."

He turned and started down the street as hidden, and the next instant the images of Tom and Fleckner had been transferred to the yard where the crooks were hiding, and the images of magazine-pistols were pressed to the backs of the real men. Then the helmet of the officer appeared in the street.

Tom gave a low whistle. There was a cry and a brief struggle, and the next moment the butler and "Sneaker Tim" stood handcuffed before the officer, and beside them were the triumphant shadows of Tom and the professor.

At their backs these two shadow-actors could hear the suppressed, excited whispers of the little company who were watching this New Year's Eve drama in the laboratory which, except for these occasional whispers, Tom in his excitement had quite forgotten. It was hard to realize he was not really in Chicago at the moment.

But he now pulled himself into his shadow part again, and in a few words told the officer who he was and why it was so necessary to get at his cousin at once. He took care not to explain that he was really over a thousand miles away. The wonderful invention was kept out of the explanation altogether, and the officer supposed he was talking to real men.

When he had finished, the policeman turned to the prisoners.

"You," he said to the butler, "will go to the station with me. You, Sneaker Tim, have a chance at saving your hide again. I'll take the law in my hands this once. This gentleman must see Bruiser Horace at once and get him to sign a paper. If he does, he'll pay you both well; and I'll see that you both have a chance to get out of the city. If he doesn't, you at least go up; and you know that means a life sentence this time.

"These gentlemen have heavy guns with them. You will get on the car with them at the corner and take them direct to Horace's hiding-place. I'll ring up a plainclothes friend of mine on the quiet, and he'll follow to see you don't get away. You'll coax Fairweather to sign this paper and it'll all be done in fifteen minutes. Not a word. Now be off."

The evil, shifting eyes of the prisoner went from one face to the other for an instant, then fell.

"All right, gents," he said. "You got me where you want me. Lead on."

A few minutes later the three entered a dark tenement-house and proceeded up an old-fashioned elevator to the top floor, twenty stories high. At the rear apartment, Tom knocked.

"We'll stay outside," said the professor. "Call us if you want us."

He and Tom then seemed to step back into the darkness of the hallway. In reality the professor turned off the projector at this point and by means of the invisible ray they followed Tim into the dark little apartment into which he was admitted by a pale, slovenly woman.

"In the back room," she said listlessly, and Tim went through a blind door in the hack of a little closet and found there the man whom Tim and his fellow watchers recognized as the one they had encountered first in the bar.

Tim went right to the point, told his pal in a few words what had happened of his meeting with Tom Priestley and the request that he sign the paper that would keep the fortune in the family. Then Fairweather broke loose.

"See here," he said or rather roared. "My father left me and the other two only one thing—a hate for the rich end of the Priestley family that nothing can kill. We all three swore before he died we'd never sign any papers to keep the fortune for the descendants of the man that cast us off. We'll die before we'll do it. No, not if you rot in prison, Tim, and I hope you do, for being a cowardly squealer."

He stopped a moment and a look of fierce suspicion came over his face that made his companion quail before him.

"How did you get here without being watched?" he demanded, seizing the smaller man by the shoulder. "I believe you let 'em shadow you, you dirty little pup. You've got us both in a hole. You'll never serve another day in prison, you infernal whelp."

There was a gasp as the big man's fingers closed around the little man's throat. The hand of Sneaker Tim shot I into his pocket. It came out again with a deadly magazine pistol.

Fairweather saw it too late. There was a flash in the dim room. The two fell to the floor together. Behind them was a shriek of terror and fury. There was a flash, and a long knife in the hand of the thin woman sank into the back of Sneaker Tim.

The pals had served their last prison sentence.

One of the three Priestley heirs had been removed. A grim ally had come to the aid of the family fortune.

CHAPTER VIII

THE DEPTHS OF MADNESS

PRIESTLEY roused himself with a shudder. Professor Fleckner had turned off the ray and blotted out the scene of tragedy. He saw only the little laboratory and its New Year's Eve company about him.

On the faces of all was a fixed, breathless horror. It was as though they had suddenly awakened from a terrible nightmare. Then from about the room rose a stir and a sigh of relief—the kind that comes to an awakening sleeper when he realizes that after all it was only a dream.

And so it was to these watchers of a violent death over a thousand miles away. As soon as it dawned on them that they were not really in the dread presence, the reality slipped from their imaginations and it became merely as a vivid tale lately read.

Not so with Tom Priestley. His was a keen sensibility and vivid imagination. The horror still lived before him.

He felt that just behind that screen still lay those two lifeless forms, and above them the shrieking woman holding poised the dripping knife. Tom shuddered and closed his eyes.

Suddenly he jumped up. This was no vision. Two real human beings had been blotted out. Another had just committed an awful act. Distance to him was nothing. They were still within instant reach.

He had a duty to perform. The police must be summoned and the doctor called. He turned to the inventor.

That worthy showed in his immobile face no trace of feeling in connection with the recent horror. He was hurrying over the pages of a gazetteer that lay on the table beside him.

"Quick!" shouted Tom. "Back to Chicago! One of those men may still be alive. We must get a doctor and summon the authorities."

The professor turned to him a cold face and his hand sought the levers of his instrument.

"We have no time to worry about the dead," he answered. "We have two more of the living to seek and twenty million real dollars to save. One of the heirs is forever out of the reckoning. I examined closely before I turned off the ray. His pal's bullet went through his heart. We have only three-quarters of an hour left in which to search the world for the others. I am now getting Bridleville, Ohio, where I trust we shall find Mrs. Samuel Foy."

Fierce anger gripped Priestley. To his highly idealistic mind, the professor's conduct and words seemed the height of the sordid. That the man should neglect suffering humanity to save mere dollars was to Tom inconceivable. It was the million promised the professor that had inspired his unholy zeal.

Tom dashed forward, hardly knowing what he intended to do, but instinctively bent on returning to that chamber of death where he felt his duty lay. He was caught by the shoulder and forced back into his chair.

"Be still, Tom," said a voice over him. Tom looked up into the face of his old chum, Slade.

"Don't be a fool, Tom," continued Slade. "You have too much at stake."

In the eyes of his old friend, Tom saw also the motive inspired by the promises of another sordid million. The man who a little while before had congratulated him on losing his fortune, now that he had a personal interest in it, was ready to desert for it his suffering fellow men, for whom he had always professed such zeal.

Tom closed his eyes in sick disgust and took no further interest in what went on about him.

Meanwhile the professor was rapidly manipulating his little levers. On the screen before them went flashing by a long stretch of country. Off across the snow-covered landscape were spread broad, beautiful estates.

The moonlight gleamed on their white lawns, gables, and turrets, and broad expanses of greenhouses in which the rich kept their famous winter gardens of the temperate zone. Alternated with these estates were the broad parks in the midst of whose leafless trees shone the light of hundreds of suburban cottages.

All this sped by in an instant of time. They were following one of the great monorail trunk lines. Four big bands of glistening steel, with their guide-rails overhead, were sliding past the watchers. Now and then, with a flash and roar, a train of big palace-cars, each the size of an early-century yacht, would speed by. Suddenly the moving panorama stopped.

They were at a railroad station, and around it was spread out one of the few remaining old-fashioned villages, a hundred or so houses irregularly lining the half-lighted streets.

The towerman bending tensely over his levers, and the night operator half asleep over the clicking instruments in the little station, were the only living persons around. Through the still air came the sound of voices and laughter, where in all probability the socially elect of the village were holding a New Year's Eve meeting.

The professor turned an inquiring look at Priestley. That young man was slouching back in his chair, sullenly indifferent. Fleckner saw he could hope for no help from him, so, again putting on the hat and coat he had been wearing when projecting himself to outdoor scenes, he swung the projector on himself and his image stepped onto the station platform in Bridleville.

The next moment he stood over the drowsy form of the operator. Instinctively he reached out a shadow-hand and touched the slumberous one on the shoulder. Then he laughed to himself as he realized that he had no flesh and blood available out in Ohio.

He resorted again to the expedient of stamping on the floor in his New York City laboratory. The sound at once awoke the operator.

"Pardon me for disturbing you," said the professor politely, "but can you tell me where I can find the home of Mrs. Samuel Foy?"

The young man started visibly, as though the professor's apparently innocent question had stung him.

For a full minute he looked over his visitor with cold suspicion.

"What do you want of Mrs. Samuel Foy?" he demanded in a sullen tone.

"I merely wished to learn from you where I might find her," replied the professor with some dignity. "If you are unwilling to tell me, all right."

"I don't know anything about her," said the operator with finality. "I don't think you'll find anybody around here who does, either."

Without further parley, Fleckner withdrew his image, and as soon as he was outside the station flashed about the village in search of some more willing informant.

The next instant he saw coming toward his projection an individual of unsteady gait. He was evidently a. New Year reveler who had reveled too enthusiastically for a country village, and had been left to complete the festivities of the occasion by himself.

Not a very promising outlook, thought the inventor, but worth trying.

He stopped in front of the man and was greeted with the utmost enthusiasm.

"Can you tell me where Mrs. Samuel Foy lives?" asked Fleckner.

The man swayed back and forth unsteadily, and then reaching out, placed, or sought to place, a supporting hand on the enquirer's shoulder. The hand passed through the professors immaterial body and dropped by the side of the inebriated one. He started violently, then pulled himself together.

"Schuse me, shir," he apologized, "my mistake; can't calculate dishtances very good in moonlight. Never could from boy. Schuse me, sir,"

Once more he reached out, this time with the utmost deliberation and calculation. But the professor, not wishing to carry this test too far, side-stepped, and the man finally found his needed support on a lamppost only two feet away.

"Tell you what," he said in a confidential whisper, after a moment more of swaying, "I ain't supposed to know, but I drove horse fer Doc Pierce till he fired me. Said I'd get even with him. I heard that name before, Mrs. Samuel Foy, Mrs. Samuel Foy. Don't nobody know round here. Ask Doc Pierce. He knows, but don't tell him I said so. He'd kill me."

Having thus delivered himself, the inebriated one meditated a moment, then slid quietly down the lamppost and went to sleep on the icy curb.

"He'll freeze, poor man!" whispered a woman's voice from the back of the laboratory.

But the professor, busied with his levers, paid no heed.

Now the screen showed the front of the lighted house in Bridleville from which came the sounds of mirth. Professor Fleckner's figure stood on the steps. A few raps by the real Fleckner on his laboratory table brought a young woman to the door.

"Pardon me for disturbing you," said the caller urbanely, "but could you tell me where I can find Dr. Pierce?"

"He lives at the end of the street, but he is here this evening," answered the young woman. "Wait a moment, please, and I'll call him. Won't you come in?"

"Thanks, no," replied Fleckner. "I'll stand right here. I only want him a moment."

A few minutes later, in response to the young woman's call, a jovial person appeared and stepped out on the porch.

"I am Dr. Pierce," he announced. "What can I do for you?"

The professor had heard enough in the last ten minutes to be convinced that strategy was necessary.

"I am an old friend of Mrs. Samuel Foy," he said, "and being in town over night, wished to call on her in the morning before leaving on an early forenoon train. Can you tell me, please, where I may find her and if she is well enough to receive callers?"

At the mention of Mrs. Foy's name, the doctor's urbane expression vanished. He glared searchingly at his caller for a full minute.

Then he seemed to recover himself and said hastily.

"I am sorry, sir. It will be impossible to see Mrs. Foy. I am obliged to keep the unfortunate woman in the utmost seclusion. It will be no satisfaction to see her. Mrs. Foy has been a hopeless maniac for over ten years."

CHAPTER IX

A PLOT UNEARTHED

"NOW, Professor Fleckner," said Priestley, starting up, "that ends our search. If this unhappy woman is insane, she can sign no valid paper, and there is no use of continuing. I thank you for your effort. Now, however, we have a human duty—the one I urged upon you before. Please return to Chicago and see if we can do anything for the men we left apparently dead, and that poor woman who was so unfortunately mixed up in the tragedy."

"Not so fast, not so fast, my young friend," rejoined the professor. "One of the secrets of my success is that I never give up. I must see this alleged crazy woman. There is something under the surface in this strange case."

While he was speaking Professor Fleckner was rapidly moving his levers, and Priestley, despairing of gaining his point, now realized that there was a series of private rooms being thrown on the screen. The inventor was examining each house in the little settlement at lightning speed.

No secret chamber could withstand his penetrating ray. It was clear to the watchers that if this great invention came into general use, and was not in some way curtailed in its action, personal privacy would become a thing of the past.

A moment later the professor stopped with a sigh. Every house in the village had been searched. There was no one revealed that in any way suggested a mad woman.

Then, still undaunted, he went at his levers again. This time he threw on the screen a bird's-eye view of the town. Then was discovered what the manipulator of levers had before overlooked—a low, dark-brick house, out on the end of aside street, far back in a grove, and shrouded in darkness suggestive of deep mystery.

Into this plunged the privacy-destroying ray. Room after room was laid bare on the screen. In one was a slumbering woman. In another lay two small children, asleep in a crib. They were at first the only living beings exposed by the ray.

Then suddenly a turn of the controlling lever brought out a strange little apartment. It was in the top of the house. under the center of the roof. The one window was barred. The heavy door was double locked. The furniture was meager. Everything suggested a prison.

But what at once attracted the attention of the onlookers was a lone figure in the center of the room, that of a woman neatly dressed in black. A rather refined woman of a little past middle age. Her hair was snow-white, and her face denoted long suffering. Yet the eyes. though wet with recent weeping, were clear and reasonable.

She sat, her back to the door, chin in hand, and elbow resting on the little table. looking far into the distance that could be seen only with the eye of memory.

"That cannot be the woman," said one of the watchers at Priestley's elbow. "She does not appear crazy."

Priestley looked up, and recognized Dr. Cyrus Rumsey, a nerve specialist, one of the guests to whom he had been introduced that evening during the recess in Professor Fleckner's experiments.

"Professor Fleckner," said the doctor, leaning forward, "pardon my breaking in, but if you find the woman for whom you're searching, I may be able to tell if she is crazy. You seem to doubt the Bridleville doctor's story."

"I do doubt his story," replied Fleckner. "I think this is Mrs. Foy, a prisoner, and as sane as you or I."

The professor knocked on the table as he spoke, turning the projector so that the sound was directed at the outside of the barred door.

"Yes?" said the woman within, in a clear, rational voice.

"Don't be alarmed. I am a friend. This is Mrs. Foy's room, is it now?" replied the professor.

"Yes, this is Mrs. Foy. Who are you?" wine the reply.

"I come from a relative of yours," answered the professor. "I have learned something of your secret, and have come to help you. I have some keys, and am coming in. Make no sound."

As the woman rose to face him, her eyes left the door for a moment; in that instant the professor rattled some keys against the laboratory table, making a noise like unlocking and opening a door. As the woman turned, he had projected his image into the room, and though a little startled at the suddenness of his appearance, she did not notice the remarkable method of his apparent entrance.

"We must act quickly," said the professor. "Have you stylograph and paper?"

The woman pointed to the articles, which lay with a letter-pad on the table.

"Your cousin, Thomas Priestley, heir to all the family wealth, has just learned of your whereabouts, and sent me to get you to sign a release of the estate," went on the professor. "You may understand that it reverts by your grandfathers will to the United States government at midnight tonight unless all the heirs sign off."

To the relief and surprise of the professor, and, in fact, of Priestley—who was interested again, in spite of himself—the woman grasped the stylograph eagerly.

"Nothing can give me greater pleasure," she said, "if you can only get me out of this place. For two years my step-son, who is the night telegraph-operator for the Monorail here, has kept me prisoner. It is all a plot of Horace Fairweather, who, if he is my brother, is an arch devil. I suspect that Thomas Priestley's lawyers in New York are in it, too.

"You see, they discovered a previous will of great-grandfather Andrew Priestley, leaving all the estate entailed to his oldest daughter Jane, my grandmother, to be handed down to the oldest child in each generation of her descendants. Then my poor father, Maurice Fairweather, oldest son of Jane, ran wild, and grandfather cut off our branch of the family, making the will that left the estate to his son and son's heirs.

"Now it seems the old will was not destroyed. The lawyers and my brother Horace hoped to let the terms of the present will lapse and the estate go to the government. Then they would show that great-grandfather made the second will because he was deceived into thinking my father was dead. So they hope to have the later will set aside and the original will hold.

"They have kept me prisoner, giving out that I am crazy, so Horace, the next younger than I, can get control of the fortune. You have come in time to save it all.

"But, no! What am I thinking of? Horace will not sign it. I can do no good. And my other poor brother—no one knows where he is. You must have us all."

"Don't fear," said the professor coldly. "Your brother Horace is dead, and we will get your other brother's signature tonight. We have him traced. Write what I dictate at once and sign it. I have no time to lose. Tomorrow I will come back and release you."

Quickly overcoming the shock of this brutal announcement, which, however, seemed to affect her little, the woman took the stylograph and wrote as follows at the professor's dictation:

I, Ada Fairweather Foy, in full possession of my faculties, and of my own free will, do hereby release all claim that I now have, or hereafter may have, on the estate of the late Andrew Priestley, my great-grand father.

Ada Fairweather Foy.

"Goodby, Mrs. Foy; I will see you tomorrow," said the professor, and as the woman turned to lay aside the writing materials he vanished.

In the laboratory in New York lay an exact reproduction of the paper drawn up in Bridleville, Ohio, and to it Mr. Brewster put his signature as notary.

"How about that woman. Dr. Rumsey?" asked the professor a little anxiously of the nerve specialist.

"Perfectly sane," answered the doctor. "I'll take my oath to that."

CHAPTER X

A MYSTERY OF THE SEA

NOT a moment did Professor Fleckner waste for comment.

"Thirty minutes left till midnight," he remarked half to himself, stepping over to a bookshelf in the back of the room. From it he took a volume, which he hurriedly consulted.

"George Harvey," he murmured, rushing back. "That's the chief engineer of the Intercontinental Monorail Company. I've got to trace George Fairweather, our third and last object of search. Our only clue is that three years ago he was with an engineering gang on this road."

Frantically the professor grabbed the street directory on the table and turned to "George Harvey." His business office downtown was given, the New York offices of the Monorail, but his home was merely Chicago.

With a muffled exclamation of impatience, the professor threw over his levers, and the next instant a Chicago street was again racing by on the screen. In a moment it paused at the sign of a drug-store.

Then there was a waving image of the interior of the store on the screen, and suddenly appeared a succession of magnified pages of a Chicago city directory.

At "Har—' the page shifting stopped, and the professor placed a triumphant finger on the name of George Harvey with an address at No. 721 Michigan Avenue.