Help via Ko-Fi

THERE WAS LIGHT girlish laughter from behind the high hedge of old box. The flounce of feminine skirts showed under the thick leaved branches.

"Miss Priscilla seems to be enjoying herself," said young Captain Kenyon with a quick smile at the old ship owner.

Gideon Wing chuckled and his shrewd little eyes danced as he sucked in his sunken old cheeks and nodded.

"Seems so, don't she?" he cackled. "But why not, with a handsome young skipper to entertain her, eh?"

Kenyon beamed and lifted a hand to his huge new necktie. A glow of satisfaction suffused him, His success in working his way up to command of a Wing vessel scented about to be crowned with a chance to marry into the wealthy family, for the old man's evident delight could mean nothing less than his approval of such an arrangement.

Then a deep masculine voice rumbled beyond the box, and Amos Kenyon felt his elation flow away. Flushing angrily, he stared down at the matched flags of the walk, where Gideon Wing's ferruled cane was thrusting at a crack as if to frustrate the tiny ants toiling there.

Captain Kenyon knew that voice. From childhood he had competed with its owner, Burden Chase, at every turn. Now they were both masters of Wing vessels, and evidently rivals for Miss Priscilla's hand. Perhaps—and his heart chilled at the thought—the reason the Petrel loitered at her wharf, although ready for sea before the Albatross, was that the daughter favored Chase.

"Burden," called the girlish voice, "I'm sure you'll win. I have every confidence in you. But I promised father—"

Amos Kenyon thrust his dark young face forward through the gap in the hedge. Keen eyes focused on the girl's face, he bowed low.

"Did I hear you mention something about winning?" he asked jeeringly. "What's the competition? Burden and I have always been contending for something or other all our lives. If there's a contest on now, I want to enter—especially," bowing low again, "if you are to be the prize, Miss Priscilla."

"She's not to be," said Captain Chase quickly.

Kenyon laughed shortly. "She's sure you'll win but isn't game to offer herself as the reward. Evidently she either dislikes you, Burdie, or hasn't as much confidence in you as she claims in private."

The words did not cut half as much as the tone. There was studied taunt in his smile, in the curl of his lip, in the belligerent way his throat beard thrust out from under his clean shaved face. A girl with less spirit than Priscilla Wing might have been forced to answer.

"The prize is one my father offers," she said quickly.

"And you're not going to add your own pretty self?"

Her face flushed. Her dark brown eyes grew black. Her little head tossed its profusion of dark curls, and her bosom heaved under the tight lacing.

"I was about to explain to Captain Chase," she said quickly, "when your arrival interrupted, that I have promised my father not to bind myself to anybody until his race is over. If he is willing," turning her eyes fondly on the nodding old man, "I will gladly offer to go with the award."

"No, no!" protested Chase quickly.

"Afraid you'll lose?" asked Kenyon coldly.

"No, but marriage is too sacred a thing to be wagered on a race. No matter what the contest, luck plays an important part. I can't let her—"

"You can't stop her, if her father agrees," grinned Kenyon, elated as he saw the older head beginning to nod.

"Priscy," beamed the old ship owner, rubbing the gold head of his whale bone cane delightedly with a cupped palm, "you've showed your metal. A chip off the old block, you be, my girl. Always pick the winner and you can't go wrong. Just what I'd been hopin' you'd promise, but I wasn't goin' to say it. Nothin' like a good lookin' young woman pullin' on the tow-rope to bring a young skipper home in record time."

His shrill cackle of delight sent a chill down the spine of Burden Chase. Deeply in love with Priscilla Wing since she had played in pigtails with him, he felt that the girl had been fairly forced into the situation. Her father had worshipped money so long that everything else was secondary to him. Kenyon, aware that the girl favored his rival, was too eager to marry her wealth to care how much love she brought to the wedding.

As Gideon Wing led Kenyon toward the broad doorway, the girl slipped nearer to Chase and thrust a cold little hand into his great paw. Pleadingly her soft eyes turned up to his. Her mouth trembled.

"Burden, I—I had to. He dared me into it. But I knew," forcing a brave smile, "that you'd beat him."

Captain Chase smiled down at her and his big fingers closed firmly over the smaller ones. Although he knew far better than she the uncertainties of the race ahead, he buried his own doubts and fears in an effort to give her confidence. Hand in hand they followed to the dining room where dinner was waiting.

"What is this race with such a precious prize?" boomed Kenyon, as soon as they were seated. "I seem to be the only one in the dark."

GIDEON WING chuckled again; those twinkling old eyes of his darted from one stiffly erect captain to the other and then, between them and the candles, to the pretty face of his daughter at the far end of the mahogany table.

"You're wrong there, Cap'n Kenyon," he cackled. "Nobody knows but me. I've hinted there was to be a whalin' race atween you two, but I ain't told nobody the particulars. That's why I had you both out to dinner together."

Silver was fingered nervously. The girl met Burden Chase's eyes with a reassuring glance and then bent forward. "Father, please don't keep us in suspense any longer. What is the race to be?"

The old man smacked his lips over the fine Canary wine his whaling ships had brought to his cellar years before and laughed at them with his delighted eyes.

"None of your little jim-crack races, this one," he assured them, rubbing his dry old hands together. "No chase of a few miles. When I plan a race, I plan a real one."

"To the Pacific grounds?" asked Chase expectantly.

"To that Tali Mahi Island where we're to recruit fresh hands?" urged Kenyon.

Gideon gurgled with fresh delight at their eagerness to know. It tickled the old man's fancy to delay as long as possible. "Child's play," he scoffed. "Twiddle—di-dee compared to what I've in mind."

The girl at the far end of the table was leaning forward now. Her red lips were parted eagerly over perfectly matched teeth, and her eyes were brilliant in the soft glow of the candles.

"I've purposely delayed the sailin' of the Petrel until the Albatross was ready. "Not," darting a mischievous glance at Kenyon, "that it has been any hardship to either Cap'n Chase or Priscy, if I'm any judge."

He broke off to cackle at that barb and sipped more Canary. The rival skippers kept their eyes on his face, studiously avoiding each other by so much as a glance.

"I fancied that was because of the movement of the whales," said Chase. "If I'd sailed earlier I'd have had to push up the Pacific to find 'em. This way I meet them far down near the end of their swing."

Kenyon snorted. "Still following your father's crazy notions about migratin' whales?"

"Not such a crazy notion, Amos," interrupted their host. "Lemuel Chase's theory was founded on solid fact, as I'll show you later. But it warn't altogether for that I delayed sailin' for you, Burden. I wanted to start you off on this race. It starts, gentlemen, when you leave this house tonight. It will end," he paused dramatically, "when one of you steps ashore on a Bedford wharf from a full ship, full to the top chime of the last cask with sperm oil."

The immensity of that order silenced the three. Miss Priscilla's hands gripped the table but she was first to find voice.

"And the prize, father?" she barely whispered in the awed silence, blushing with the memory that she had promised herself as a part of the reward.

"There's prize enough for me already offered, without his adding a thing to it," boomed Kenyon heartily, turning to smile at her.

"But I've another prize, and a good one."

Wing sucked his old stumps of teeth noisily, glad to renew the suspense again.

"You've doubtless heard of my plans to build a bigger vessel for the flagship of my fleet? I planned her for Cap'n John Avery, but he died before I got the keel laid. John, as you know, was the line's most successful whalin' master."

Eager breathing could be heard in the sudden quiet as he paused.

"The first of you two home with full casks gets that ship and the command of the fleet."

Too overcome with the prospect for flippancy, the two youthful skippers sat staring at him until the girl's voice broke upon them.

"May the better man win," she toasted, lifting her Canary high and looking deep into Chase's eyes before bestowing a glance tinged with disdain on the scowling Kenyon.

"He will," roared Kenyon, lifting his glass high, "and he'll hold you to that promise. Here's to a quick run and a good race."

"Now," grinned their host, as the glasses were returned to the table, "Priscy will excuse us and we'll go to my library. I've somethin' to show you there."

Both captains were instantly on their feet, bowing awkwardly as the girl curtsied to them in turn and swished away, casting a dazzling smile back over her shoulder at Chase as she swept up the winding stairway that led from the broad hall outside the dining room door.

"This is the how of it," explained Wing, all business as he seized a pointer that fairly trembled with his excitement. He turned to face s huge map of the Pacific that was spread across one wall of the room. "Cap'n Lemuel was right about sperm whales migratin'. I've proof they did!"

Then, as Kenyon sniffed audibly, being a staunch believer that whales were merely notional in their travels, the old man fixed him with a glittering eye. "Study them pins. Each marks where a sperm whale was killed by a Wing ship. The flags on 'em carry the dates, as well as the ships that killed 'em."

The two stared at the evidence. Making a great sweep around almost the entire ocean, those pins formed a mighty capital C of irregular outline. At a group of islands south of the equator the pins ceased, leaving an expanse unmarked until they again renewed, thick near New Zealand and sweeping southeastward into the Antarctic.

Burden Chase nodded, while Amos Kenyon stared.

"One thing's left to find out," explained the old man sadly. "That's where the whales go from them islands south."

"Didn't John Avery know?" asked Chase at last. "My father always thought he did."

Wing nodded, his thin nose stabbing the air. "Exactly," he agreed. "That's why Cap'n Avery beat every other skipper in the Pacific and filled months afore 'em. He killed sperm whales all the year 'round, instead o' losin' track of 'em for two or three months below them islands."

"But you've got his log books. Find out from them," suggested Kenyon inanely.

Wing scorched him with a glance of contempt. "I've brains enough to do that—if it could be done," he snapped. "But he never entered his position from the time he left them islands until he met the fleet again off New Zealand. It was a secret he kept, even in death."

"But his mates would know," protested Kenyon.

Wing laughed drily, his old eyes hard. "Would they? Not if Cap'n Avery didn't want 'em to, they wouldn't. Know what he did with 'em? Kept his mates locked in their cabins for a solid week, kept all charts and navigatin' instruments locked away from 'em until his ship j'ined the others. Only let 'em out o' cabin to take the boats after whales and to boss the cuttin' and b'ilin'."

"But his helmsmen—"

"Was, every last one of 'em, Kanaka Islanders durin' them months. That's how he kept his secret and was killin' whales a-plenty while every other ship was idle."

HE RATTLED the pins in his hand, shook his head at the map.

"It I could only stick in these pins, gentlemen, I'd be a happy man. It would make a deal of difference if my ships could work twelve months every year instead of nine or ten."

He tossed them on the desk and picked up a well thumbed hook with a cover of imitation blue marble. Opening at a marker, he fairly stabbed one thin finger at an entry. Both young captains bent forward to read.

"This Day a Native Whale Man did Promise to Show Me the Way of the Sparm Whales Southward from This Island in Return for Services Done Him in Heeling Him of a Sickness which Yielded to my Medicines. This Way is a Sekret Knowed only to his People and not Ginerally told to White Men."

"And you believe that?" sniffed Kenyon.

"Records prove it," insisted Wing curtly. "Every year after that, when John Avery was in the Pacific, he took sperm whales while ev'rybody else idled. I'd give ten thousand dollars, gentlemen, in cold cash to the skipper who could bring me that information."

"It's like lookin' for one big pearl," grinned Kenyon. "A full ship and a quick run home'll suit me."

Burden Chase said nothing but he went to the chart and studied the neighborhood carefully. Gideon Wing watched him, smiling to himself.

"Better take a look at that course them whales follow, Amos," said the old owner quietly. "Keepin' that sweep in your mind'll help you fill faster."

Kenyon bent and passed a thick finger end around that curve, muttering the names of the nearest points, memorizing. Although he had scoffed previously at this theory he could not laugh at the telling evidence of those little pins.

"That," said the old owner, snapping his massive watch shut, "completes my instructions. The tide turns within an hour. Get your horses ready and I'll start the race in proper manner. Line 'em up in the drive, headed for Bedford. I'll fire my pistol for the start. Remember, the finish is to be when one of you shakes hand with me on the wharf with a full ship safely home. Now away with you." Gravel crunched in the wide drive as the two hired livery rigs swung abreast of the steps where the old man stood with raised pistol. Before him the Dartmouth meadows swept down to cornfields that led to sand dunes and salt water, gleaming under the stars. Then a sash lifted over his head and Priscilla was framed in the window, her face beautiful under the soft glow of the candle she sheltered with one cupped hand from any vagrant breeze.

"A swift race and a fair one," she called. "May the better man win."

"Thanks," called the rivals in unison. The old man's hand jerked with the discharge, and the startled horses leaped forward.

There was not enough room for both those hired chaises to go abreast between those massive stone posts at the end of the driveway. It was a grim battle down the gravel to see which should be first through. Down the gravel the horses tore, neck and neck.

On and on tore the straining beasts, eager to be home. The two captains urged them faster and faster with slapping reins and cutting whips. Neither one seemed in the least inclined to slacken pace.

"Give way or you crash," roared Kenyon, yanking his horse's head to lunge him against the galloping grey.

"Smash and be damned to you," bellowed Chase in reply, dragging on his own rein to get the same result.

The horses went through side by side. The light wagons, driven hub to hub as the horses collided, were suddenly smacked resoundingly into those solid stone posts. Wood splintered with a crash, two figures, the reins wrapped around their wrists, went flying over the dashboards, and a trail of wreckage and gliding humanity went streaking off down the dirt road, raising a cloud of dust in spite of the heavy dew that had come in, salt from the sea.

The girl screamed, but her father only danced about with glee, chuckling at this evidence of spirit. Then he cocked his head and listened to the shouts, curses, and commands that came fainter and fainter from the road, as the terrified horses dragged their unlucky drivers farther and farther away.

"I'll be down to Padanaram to see you off," he shouted after them. "See that you've sea room passin' the islands. I can't have you wreckin' my ships like you wrecked them chaises."

The shouting stopped. The girl's voice floated down to him, full of quick pride.

"They're mounted and gone, father, but Burden's grey is ahead."

GIDEON Wing was still chuckling to himself when he came down before daylight to clamber into his own chaise the negro hostler held in readiness.

"Just a minute, father," called Miss Priscilla, fluttering toward him through the dim light. "I have an interest in that race, you know. Make room for me there beside you."

They rode down to the very edge of the shore and waited, breathless.

Down the long harbor, their sails stretched like the wings of some mighty seagull slanting before the wind, the two sister ships stood out upon the long run that would carry them southward around Cape Horn and thousands of miles beyond into the Pacific before they would strike the island where they were to enlist more men for their crews and start the pursuit of the monster whales.

The rising sun tinged the new white canvas with rose, the black hulls glinted with fresh coatings of paint, and white water creamed in a bone at each blunt bow as the heavy ships went streaming off toward the distant sea. A rooster on the Albatross crowed lustily and a crated pig on the Petrel squealed in terror. Then conch shells brayed a greeting as keen eyes spotted owner and daughter on the shore. Colors dipped. Guns boomed. A faint cheer from the crews wafted to their ears.

"Neck and neck," chuckled Gideon Wing, nodding as the two ships forged past. "Like them two always have been. Either one of 'em'll make you a fine, respectable husband, girl. Get this silly romance idea out of your head while they're gone, and take the one as leads home."

"I have promised that I will," said Miss Priscilla meekly, although her eyes never left the Petrel to give the Albatross a glance.

"Good girl," he murmured, patting her hand with his own dry palm. "I can't loiter around here forever on borrowed time. Got to be thinkin' who'll carry on for the Wings."

SIDE by side the two barks went tearing out toward the sea. Mishaum Point slipped astern. They breasted Penikese Island and then Cuttyhunk. Gayhead, on the end of Marthais Vineyard, saw them separating slightly, but no observer could have told which one was leading. Then No-Man's-Land, that possible stopping place of early Norse visitors, was behind them and only the open Atlantic before.

"Clap studdin' s'l yards on her foremast," ordered Chase, after a scowling survey of the Albatross.

"Think she'll stand 'em, sir?" asked Abel Trueman, mate of the Petrel, his seamed face anxious.

Any other master of the time would have reprimanded him roundly for that seeming questioning of authority, but Burden Chase had early established the custom of getting opinions from his officers and even from his men.

"We'll try it anyway," he called with the finality that they all knew and respected. "If we've poor yards we might as well know it now. We've got to be first at the island to get the pick of the men. A lot depends on that. Bend 'em on, mister."

The men were taken from the task of stowing down the clutter on the decks and sent aloft to spread extra canvas to the light breeze. The bark plowed almost directly eastward, to cross the Gulf Stream and evade the upward sweep of its powerful current before heading southward toward the distant Horn.

The sails went up slowly in spite of willing hands. The need for men in ever increasing numbers for the whaling vessels that left these parts had already stripped shore and farm of the most promising and ablest. Of late, ships must put to sea with green hands who must be whipped into shape enroute.

The wind increased. By noon the Petrel was tearing eastward like a runaway horse, heeled far over under the strong southwest wind, her cordage creaking. Far to port and dropping steadily astern as those studding sails gave the Petrel a decided advantage, the Albatross was plainly taking their wake.

"The pick of the islanders," mused Captain Chase, well pleased with his lead. "Good crew often means a quick loading."

A slight squall struck them. They heeled swiftly, came up from under the impact. Captain and mate exchanged glances. The mate, older, more cautious, shook a doubting head.

"We've good spars aloft," exulted Chase. "We'll beat 'em to Tali Mahi."

Another squall brought a threatening crack from aloft. Then, even while mate and skipper prayed it wouldn't happen, the cracking fore topmast crashed under the fierce tug of another gust in the billowing white. Yards toppled, stays snapped, canvas fell with the swaying flutter of a giant crippled bird, to thrash and pound and flap in a wild eagerness to be free.

Before anybody could move to cut the wreckage away, another and another fierce gust hit them. The main topmast, burdened by that unusual forward drag, snapped its stays and pitched with a crash.

"Up and into it to cut away before we're dismantled," screamed Captain Chase. Then, as his men loitered, afraid to venture aloft, he leaped past them.

Any other master would have snatched a belaying pin from the neighboring rack and smacked heads with it. But Burden Chase knew that these were farm lads instead of sailors. The roll of the sea had turned many of them a ghastly green with seasickness already. A little kindness in leadership now might bear big dividends in the long cruise ahead.

"Follow us, men," he roared, and waved Trueman into the lee rigging while he went to windward.

Even as the captain hurled by, he snatched a knife from the sheath on the hip of a goggle-eyed starer. With the blade between his teeth, he swarmed up the ratlines. Eyes ?ashing, arms reaching, legs pumping madly to carry him up the ropes, he fought to get aloft before that wild mare's nest could carry away the mizzen-top as well.

His left hand held firmly to the stay, the knife flashing in his right. The keen blade sheared hemp, sent billowing canvas to spill harmlessly and relieve the strain on threatened gear. Behind him swarmed the men and Trueman. Their own knives out, their fumbling hands eager to follow the example he set them, they were doing their best to help clear.

Meanwhile the helmsman, at the nod the captain had given him as the mast snapped, had headed them up into the wind to relieve the strain on the gear left standing. With some of the sails aback and the fallen canvas a tangle, they wallowed in the rising seas while the Albatross drew swiftly abreast, brought near enough for her exultant skipper to send his hail booming down the gusty wind.

"See you in Tali Mahi," jeered Kenyon,"—if you ever make it. I'd throw you a tow rope, only I'm sure nobody aboard you is seaman enough to make her fast."

Then the wind carried him past, leaving the Petrel fluttering like a bird with a broken wing in the gathering dusk.

GRIMLY Burden Chase drove his men to replace that damaged gear with new from the supply lashed on deck. Grimly he searched the horizon during the long weeks that followed as they crowded on sail and hurried southward. But no sign of the rival bark appeared as they raced through the tropics, fought westward around the Horn, and tore across the broad Pacific.

Not until they raised the jagged outline of the island where his owner had instructed him to seek fresh provisions and new hands did he sight those familiar topmasts again. Then he saw the Albatross sweeping grandly out from the harbor, her yards filled with triumphant men jeering and mocking the slower ship.

There was no time for a gam, but Amos Kenyon could not resist the opportunity to haul alongside and tell of his success.

"Got the best of the lot," he called exultantly. "Wish you luck recruitin'. Whales reported by the fishin' canoes to the north'ard. Come up and we'll show you how to take 'em."

It was fully four hours later, after beating into the little harbor, that Burden Chase understood the full import of Kenyon's words. There had been no rush of girls swimming eagerly out to meet them, no throng hurrying to the shore. Instead the canoes were missing from the beach, the huts in the cocoanut grove were apparently deserted, and nobody stirred anywhere in sight.

Ordering a gun fired to announce their arrival, he hoped to bring back the natives, who must have gone in a body to some of their community pursuits. But the echoes rang back from the volcanic crags that towered menacingly halt a mile behind the wooded strip along the shore. There was no answering hail of pleasure such as Chase had always encountered before.

"Lower a boat," said Chase, his brow darkening. "I don't like the looks of things."

Trueman sidled nearer, scowling from under bushy brows.

"They ain't strained their selves none hangin' out no welcome signs, have they?" he offered. "You reckon you'll be safe 'thout firearms?"

Burden Chase laughed. "I've been here three times before," he chuckled, "and never needed a gun yet. I'd as soon think of taking a gun to Quaker Meeting at Russell's Mills."

The huts proved as deserted as they had seemed from the shore. There was nobody in sight anywhere.

Fearlessly he started up the path that he knew led to an interior valley where they did their limited planting of taro root. Then his blood chilled at what he saw barring his way.

Stuck on short sticks of varying lengths, their tops surmounted by cocoanut-husk hair and gaudy feathers, two score ugly masks were ranged from wall to wall of the dense jungle that lifted at either side of the narrow way. Grinning, threatening, twisted into horrible contortion, the crude replicas of fantastic human faces presented a definite check to an advance.

He knew what those masks meant. These were devil frighteners that the natives had erected to keep their enemies from following. Passing those hideous faces was the equivalent of a declaration of war, unless he was escorted past by a member of the tribe erecting the taboo.

Jumping at the conclusion that Kenyon had in some way aroused the anger of the good natured islanders, he stood staring at the masks. The inland valley was too far away for his voice to carry, even if he shouted. If he pressed on, he might be struck down by the blow of a warclub or pierced with poisoned arrows.

Thoughts of the rival bark killing whales to the northward embittered him. Unless he could find helpers on this island he must lose precious time searching for recruits elsewhere. Meanwhile the whales would he sweeping past in their mighty pilgrimage and he might see no more of them for months, giving the Albatross a lead he could not hope to overtake.

YET he stood there, respectfully bowing before the island fetish, his heart heavy with apprehension. Suddenly from the corner of his eye he detected a slight movement and turned to stare. Immobile, a nearly nude savage stood within the greenery, perfectly camouflaged by the flecks of light and shade on his painted and tattooed skin.

"Hello, there," called Chase cheerfully. "Do you understand me?"

There was no answer.

"I am a friend of Leli, the chief," Chase called. "Tell him that Captain Chase has sent his son to visit him."

There came an incredulous grunt from another spot. A second figure, bigger, older, shoved past the first. A scowling face peered out at him, the blue tattooing on the features giving the eye an appearance of startled wonder.

"You Cap'n Chase' son?" grunted the voice.

"I am. You're Hargi, aren't you? Remember how you used to teach me the ways of your people when I was so high?"

There was no confirmation. although the doubting eyes followed the measuring movement. A spear thrust through the brush, its head studded for fully three feet with sharks' teeth. Chase knew that they had probably been dipped in deadly poison. With a slight shudder he restrained the natural impulse to grasp the blade.

The native scowled and came a step closer, his eyes searching the face that had aged and matured since Chase had visited the island.

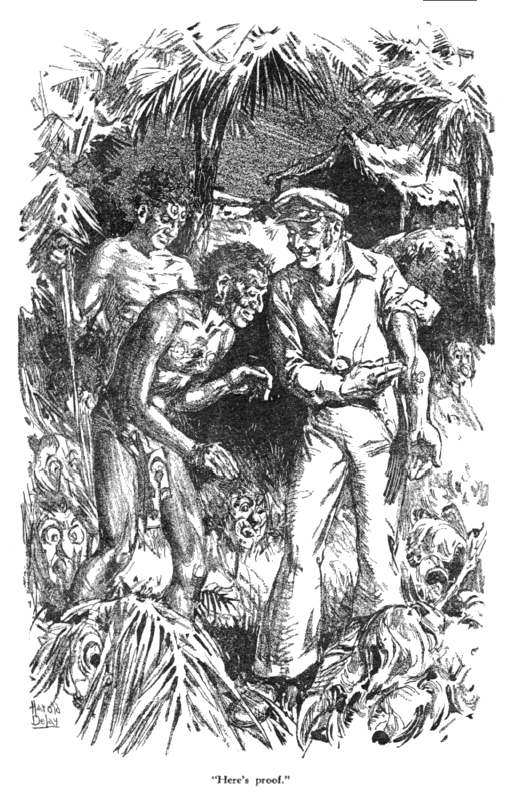

"Here's proof," grinned the captain, rolling up his left sleeve.

There in the smooth white of his inner forearm was the small blue tattoo mark that he had allowed the island expert to prick into his flesh as a sop to the man's ambition to decorate his whole body, especially his face.

Hargi looked, grunted, broke into a broad grin of delight.

"Cap'n Chase good," he nodded. "You good." Then his face darkened again. "But other white man bad."

Chase nodded, understanding. He realized that the whaling vessels often brought disease and bitterness to these trusting children of Nature. Many a skipper, short handed through desertion and sickness, had recruited by brute force in the islands. Men had often been carried away with the promise of being returned, only to find the islands thousands of miles away when the ship was finally filled and ready for home. A few of these unhappy wretches had survived the inhumanities of white cities and white sailing masters to trickle back to the islands with their tales of ill treatment and abuse.

But Burden Chase knew that he must find recruits there if he hoped to fill his empty casks with oil. Kenyon was already on the grounds, might even now be fast to a whale. If the Petrel was to have any chance in this epic race, he must fill his half empty forecastle.

"Take me to Leli," he said.

Although he was eager to be off in pursuit of the whales the canoes had reported to the northward, he knew that he must curb his impatience long enough to satisfy the grievances that the islanders held against whaling masters, or there would be trouble for the Wing ships that must often call here for supplies.

"Leli sick," grunted Hargi. "No can see."

"What is wrong? I'm a doctor like my father."

It was true, for the whaling skipper of the period must be doctor, dentist, judge, and preacher to his family. His kit included the best books obtainable on medicine and the limited surgery of the time. There was even a razor safely tucked away in black pepper to prevent rust from damaging its keen blade in the salt air, a razor that his father had lashed back with fine wire to insure a minimum of play in the handle while he amputated a man's leg that had been caught in the bight of a running line as a whale sounded. The very pair of forceps with which Lemuel Chase had taken an ulcerating tooth from Chief Leli's jaw, rotting with necrosis, was also in his kit.

Hargi lifted one hand to his tattooed face, pretending to gouge out bits with the nails. Chase understood. That must mean the smallpox, always a deadly malady among primitive peoples.

"Many sick," explained Hargi. "Many die."

Chase had stopped, even as he started to follow the native through the ugly masks. The tattooed face turned back at him.

"You 'fraid?"

Through the captain's head was racing the memory of that lecture he had heard from a doctor in New Bedford, a doctor who had just returned from Europe with new ideas from men who believed that they had found a way to defeat the dread disease, smallpox. Did he dare, limited as that knowledge was, suspicious as these natives were, to attempt to use that new inoculation on the survivors as yet untouched?

"HARGI," he began, "the white medicine men have a new magic for this trouble. It does no good for those who are sick already, but it keeps a man from catching it if he has not taken it. Have many escaped it?"

The native nodded and explained in his pigeon English. The disease had been brought by a whaling vessel. The captain had put some sick men ashore, warning the natives to keep away from them and explaining that the disease was catching. But the kind hearted natives had been unable to stay away from the moaning sufferers. Some of them had taken fruits to the sick, had caught the pox, and had been isolated themselves in another tiny island valley, where Leli was now lying ill with the dread disease. Because the whaling captain had warned of the need of isolation, the islanders had been able to maintain a fairly successful quarantine. Less than half of the inhabitants had been exposed.

"Wait here for me," said Chase with decision, as Hargi finished explaining. "I think I can save those others."

The scowling Trueman leaped for a rifle as he saw the captain running back through the grove. "I'll hold off the brown devils," he called, throwing the piece to his shoulder. "You're safe now, cap'n."

Chase grinned and sent his own voice booming out to the anchored bark. "Send my medicine kit ashore, Mister Trueman. They're sick with smallpox. I'm going to inoculate 'em."

"And bring it back aboard? We won't stand for it. The boys shipped aboard here to hunt whales, not to doctor no sick savages."

"Send off my medicine kit."

That tone in the roar should have warned Trueman, but the mate was terrified at the mention of the disease.

"I won't," he screamed. "We're all partners in the welfare of this here ship. The rest of us won't stand for such doin's."

Chase leaped into the boat, his face purple.

"Lay me alongside in a hurry," he growled.

Swift oars sent the whale boat cutting through the water. As the small craft drew to the bark, Captain Chase vaulted lightly aboard to face the ring of indignant men that backed Trueman.

"We're afraid of the smallpox," whined Trueman. "We want whales, not sickness."

Their captain turned blazing eyes upon them.

"I've been easy with you all," he began. "I've spared you all I could, for I'm the kind of skipper that believes in treating his men like men. But there are times when a captain expects to be obeyed without hesitation or argument. This is one of those times."

Trueman started to murmur, but Chase cut him short with a look.

"It's true we're here to hunt whales, but where'll we be unless we've men to handle the boats and cut in the blubber? A few days spent in getting these islanders in a friendly mood will mean quicker loadin' later."

They still loitered, hangdog and sullen.

"I'm going to tell you men something," Chase said quickly. "Gideon Wing told me, the last night before we sailed, of a secret that Captain John Avery learned on this very island about the course of sperm whales. That secret is worth thousands of dollars. If we learn it, we can be filling durin' two or three months of each year while the other ships are idle. On top of that, there'll be a ten thousand dollar bonus to the man that finds that course. I'll split that reward, according to your lays, with every man jack aboard if we learn the secret."

The shout that greeted this announcement told him that he had won them. Then he held up his hands for quiet.

"But there's one thing you've got to do, men. You've got to trust your cap'n. You've every one of you got to let me inoculate you against the smallpox, just as I'm going to inoculate the islanders. Them're orders, men."

"A murmur started. A few who had drawn away from the mate now sidled back to stand behind him. Trueman took courage.

"I'm ag'in it," he screamed. "I don't want to die away off here of the stinkin' plague, nor live through it to look like a lumber man had been dancin' on me with his caulked boots."

"Afraid of spoiling that handsome visage of yours, eh?" grinned Captain Chase.

There was a giggle at the thrust, then a mighty guffaw of laughter. Abel Trueman could never hope to win anything but a booby prize at a beauty show, no matter where the sponsors sought for talent. In the face of that remark, nobody cared to hold back longer, for the laughter had dispelled their fear.

One by one they came to Chase with bared arms and terrified faces, for inoculation was still a debated question, even among the medical men. One by one Chase gouged at those arms, completed the performance that he hurriedly reviewed from a pamphlet spread before him as he worked.

"I'm like the feller what got it back in Westport," grinned Artie Terry, the forecastle's comedian. "He said if that was only a little pox he'd hate to see a big one."

Laughing, kidding each other to hide their own fears, they submitted one by one. Finally Chase shut his bag and swung over the rail.

"Mind, I'm not promising to discover that whale track," he warned. "I'm only hopin'. If I do find it, you all share in the ten thousand. That's a promise."

Having been inoculated himself before sailing, he was not afraid of the disease. But his heart sank as Hargi led him into the valley where the formerly friendly people were hiding from the twin terrors of the white man and his disease.

Scowling faces replaced the laughing welcomes of the past. Even the women and children, usually naively friendly, scuttled into the huts with little moans of terror at sight of him. Men stood stiffly to watch them pass, frowning their evident disapproval at Hargi for bringing another white man among them.

Even the explanation that Hargi began in their own tongue as soon as he reached the council house did not assure them. Their faces remained stoical. Chase knew that his father's friendly attitude was under discussion.

"Tell them I have come to halt the disease that burns them with fever and leaves them with the pits in their faces," he offered at last.

But that translation by Hargi was far from enough. Neither was the detailed explanation of the new magic sufficient. They must know why other whaling masters did not use this magic to keep their own men from suffering. They must question and stare and shake their heads, and otherwise delay for hours that stretched into days.

Chase went to their sick chief in despair. He found him recovering from a severe attack of the disease, his eyes running, his skin horribly disfigured. There followed days of explanation to him, coaxing, scolding, threatening, bribing.

IN THE midst of these negotiations, weary with trying to win his way against ignorant and superstitious objections, the young captain was rowed back to the ship one night to find Trueman heading another minor threat of mutiny. Off to the northward, lighting the skyline, the red flares of distant tryworks proclaimed that some ship, probably the Albatross, had killed and was trying out oil, working day and night.

"This here ends our loiterin'," said Trueman savagely. "Nobody but a pack o' fools'd stick around here tryin' to save a bunch o' niggers that don't want your medicine. I'm for headin' off and gettin' some blubber aboard."

Captain Chase was tired and irritable. His temper was short.

"We're here and we're stayin' here until I give orders to go," he snapped.

"And we thought we'd shipped with a man, not a mummy cussed idjit," moaned Trueman.

Chase wheeled on him, his eyes flashing.

"I'm man enough to knock your whining words down your throat if you're man enough to stand up and take it," he snapped.

Trueman leered at him. "If I make you say 'uncle' we'll head off to the grounds?"

Chase nodded, his eyes narrow slits. "And if I lick you, you keep a civil tongue in your head for the rest of the voyage. Agreed?"

Trueman whipped off his shirt, standing with bulging muscles and massive shoulders. Captain Chase merely removed his coat and rolled up his sleeves. Although Trueman had a decided advantage in height, weight, and reach, the skipper had an equal one in calm assurance.

The men formed hurriedly, grinning at the prospects.

"Everything goes," called Trueman. "It's a he-man fight."

"Suits me," said Captain Chase tersely.

The mate rushed like a bull, his head low to butt, his great arms flailing like a windmill's. Chase sidestepped and smacked in a terrific wallop to exposed ribs as the big form went past him. The blow brought a wheezing grunt of surprise from Trueman and a roar of delight from the crew. Then the big form came charging back again.

This time the arms groped instead of striking.

But Captain Chase did not evade those groping arms. Instead he stepped quickly between them, facing the crouching mate.

The crew gasped again. Those mighty arms were around the slender waist, closing threateningly while the bullet head struck the skipper in the chest. In a quick yank the mate could have the captain at his mercy in a backbreaking snap that might cripple him for life.

But Captain Chase was no novice at this game of wrestling. Even as those great paws locked behind the small of his back and the arms began to close in a punishing hug, the lithe body twisted.

Back to the hugging giant, his own feet wide apart, the skipper bent swiftly forward, his arms groping swiftly between his spraddled legs.

It was evident to the watchers, before his hands found their target, that he was still at a disadvantage. The great mate might pick him up with a crotch hold and slam him to the deck, falling heavily upon him. Then those smaller hands found their quest, closed like a vise around one knee of the straining giant. Even as those great arms clamped tight around the slender waist, the captain threw himself backward against the great chest that was pressed against his back, pulling forward with all his strength against that imprisoned knee and sitting down forcibly upon the thigh.

The backward heave upset the mate, who could not hop back fast enough on his one free leg to hold his balance. Even as he tried a hop, the lithe captain swung ever so slightly and the mate crashed to the deck, falling over backward with the skipper landing solidly on his ribs.

That crash took all the fight out of the mate. The skipper's fall had cracked two of the big man's ribs, leaving him gasping out an admission of defeat.

As he was strapping up the side of the humbled mate, Captain Chase noted the festering inoculation mark on the other's arm and inspiration struck him.

"Terry and Manchester," he called, turning from the patient, "tumble into the boat and set me ashore. I think we've got their objections licked."

Instead of leaving the men with the boat, as was his custom, he called to them to follow and went striding off up the path. Facing the old chieftain, he bared his own arm to show his vaccination scar and then pointed to the two pussy inoculations.

His detailed explanation won the day. The old chief grinned, exposing toothless gums. Excited at the prospect of saving his people, he called in the interpreter.

But not all of the natives would accept the inoculation. More independent than most sovereign peoples, they insisted upon the right of refusal. "It's all right with me," snapped Chase, sick of bickering. "I'll give it to those who want it. The rest can take their own chances."

HE WORKED diligently, spurred on by the renewed grumbling of his men, who saw those pillars of black smoke by day and red flares by night to convince them that Kenyon and his crew were taking whales to the northward. When an excited fisherman came running in from the reef where he had been spearing fish to report a whale lying in sight just off the island, Captain Chase could no longer restrain them. Trueman, ignoring his stiff side, tumbled a crew into his boat and went pulling out through the surf.

Watching with interest, the skipper saw the bow oarsman boat his short oar and lift the harpoon as they slid toward that huge black carcass. The muffled cry of Trueman came wafting over the snore of the surf to reach his ears. "'Vast rowin'. Let him have it, Norman! Stand by to back water, men. Norman, you lubber, iron him! Dart! Dart!"

Suddenly the small figure in the bow bent backward, heaved the clumsy harpoon with its whipping tail of hemp. The weapon arched high, turned point downward, and sank deep into the yielding blubber to bury the barb in solid flesh beneath. Instantly the men churned backward on their oars, the harpooner danced aft down one gunnel to take his place as boatsteerer, and the mate ran forward along the other to tend the whipping line. Even as this complicated maneuver was taking place the monster lifted his broad flukes, rolled his blunt head under with a mighty surge, and flashed from sight with a lunge that brought his great tail down upon the water with a spiteful smack scarcely two fathoms from the retreating boat.

Trueman's cheer of defiance, as he bent to tend the line that smoked overboard through the groove in the bow, followed hard on that resounding echo of the slap. Captain Chase grinned with delight as the boat whirled and shot seaward in response to the tug of that running line, as the mate caught a turn of it around the Samson post in the how.

"Shall we up anchor and after 'em?" called Second Mate Hart, his rueful face expressing his disappointment that his own boat had not been in at the harpooning.

"No," called Chase, from where he was inoculating doubtful islanders under the cocoanut trees. "let 'em tow back if they kill. A good long pull at the oars might take some of the restlessness out of 'em. Besides," waving toward the watching Leli, "they haven't had any whale meat on the island for months and they're hankerin' for a feast."

"But they might be capsized lancin'," protested Hart, who also itched for action.

"Send a lookout aloft to get their bearings. If they're not back by mornin' we'll put after 'em. A good soakin' in brine might help Mister Trueman's ribs—as well as his disposition."

But there was no need to put after the boat. The lookout reported by dusk that the boat had killed and was towing slowly back toward the harbor. It was long after dark before a faint cry from the sea announced their return. The whale had been lanced some eight miles away and the men were exhausted from their long pull, inching that monster shoreward by incredible labor at the oars.

"Whyn't you come down for us?" snarled Trueman. "You'd wind enough and to spare. My men are half dead from the rowin'."

Captain Chase grinned at him, refusing to retort angrily. "It's a pity you didn't get a chance to pull some of your fight out of you," he chuckled. "I thought it'd serve the same as snappin' a few more of your ribs to keep you in your place. Besides, I wanted the whale here."

"To rot and smell to heaven? The natives'll hardly thank you for the perfume."

Again Chase grinned at him. "You're new to the Pacific, Mister Trueman," he said. "These natives like whale meat."

Trueman snorted. "By the time we're through takin' the blubber in the heat, the meat'll be spoiled."

"For our tastes, but not for islanders. The stronger it is, the better they like it."

THE return of the natives to their shore village the next morning attested to his wisdom in having the whale towed back for trying out. Everybody on the island able to travel was on hand. The harbor fairly teemed with chattering men, gay girls, and laughing children. It was a gala event.

Even as the crew swung the carcass into position and lowered the hastily rigged cutting stage, the visitors filled the water alongside and squatted all over the decks. Friendly, cackling in high-pitched voices, or purring in softly slurred vowels, they watched with the eager eyes and licking lips of the half starved in anticipation of a feast.

Chase chuckled at the sly craft of some of the visitors who had attained the decks. One old fellow trailed behind him a fishline as he swam from the shore. As the great blanket of blubber came slowly up the side of the ship to flop down on the deck as a fresh hole was made farther down and another great hook inserted in the greasy mass to relieve the first, he grinned and blinked at the men on the cutting stage, slashing away with long handled spades to flench the blubber from the slowly rolling body in the water as many hands tallied onto the falls and inched up the great hooks. As eager tools sliced the released slack of the blubber blanket into long strips, others chopped these strips into chunks about a foot square, which would later go to the mincer to be cut in leaves an inch thick, called "prayer books," which would be ready for the boiling down. The old watcher, with eyes as cunning to watch against detection as the shrewdest thieving monkey's, pounced on a chunk of severed blubber, tied his fishline around it, jerked smartly on the end that led to the shore, and grinned with impish delight as the prayer book plopped overboard and went coursing off under water, pulled eagerly by some accomplice on the beach retrieving for him.

Soon the old native plunged overboard to go swimming off ashore. In less than half an hour he was back again, with his line fastened to his big toe, to renew the procedure. In the course of the afternoon he sent half a dozen chunks to those waiting friends and relatives who gathered around with the eagerness of starving souls to sink their teeth eagerly into the raw fat and gulp it down in huge chunks, smearing their faces grotesquely with the grease.

Still another of their good natured thieving visitors spent fully three hours squatted on a hatch cover with the metal ring between his legs. Whenever he thought himself unobserved, he bent and inserted as many fingers as he could in the ring and tugged violently until the sweat stood out on his forehead and the veins were near to bursting in his efforts to steal the ring, all unaware that it was bolted to the hatch and that he could not pick it up without lifting himself as he sat there. He would desist whenever any of the crew appeared to notice him, only to snatch at the little ring again and resume his tugging the instant he felt he was unobserved, as if he expected to catch in an unguarded moment also the evil spirit that held the thing 50 magically against his pulling.

Meanwhile the work went on with a will. The huge hook carried for that purpose had been inserted in the head of the whale while the rest of the crew was engaged in the rigging of the stage. The neck had been severed, too, while the blanket was being started, so that the front third of the mighty beast could be cut away for the preservation of the case and its valuable spermaceti content. Then, with the great head left dangling, to be attended to later, all hands swarmed to the task of cutting in that blanket, that the body might be turned over to the natives as soon as possible.

Eager brown boys and men leaped to carry out every suggestion given by men or officers. Never before had Captain Chase seen a whale stripped so swiftly.

Men and boys laughed and slapped at nearly nude girls who draped themselves in alluring postures over every available bit of deck or hung from the futtock shrouds to ogle down at them. The air resounded with giggles, kisses, laughter, and jeers.

"Leave go that little beauty, Ike Brown," roared a jocose voice, "or I'll tell your Miranda on you."

"You're a fine one to talk, Mart Davol, with your Nancy to home lookin' after your forty-'leven brats while you're lallygaggin' with two-three pretty gals yourself," retorted the unabashed Isaac, returning instantly to the pleasure of soft lips that were delightedly learning the joys of the white man's habits.

Blood and grease spread over the ship and the workers. The tropic sun burned low and night was upon them. The mincers clattered and sliced away over the hogsheads, chopping the chunks of blubber into leaves held together by a bit of skin but separated to allow the heat to penetrate quicker and thus facilitate the cooking down.

With the coming of darkness the fires were lighted in the brick tryworks. The great kettles were filled with the chopped fat. Sputtering and hissing, the cooking turned from bloody white daubs to the hot and swimming oil that must be skimmed and bailed into the cooling pans before being transferred into casks.

The excitement scarcely lessened with the darkness. The ?res gave sufficient light to carry on the task of cutting in. The crew stood watch and watch, but the natives remained in a body. Couples slid into dark corners for secrecy. Girls crowded into cabins and forecastle, unabashed by any feeling of impropriety. Success was upon them. The sea had yielded its treasures. The island was saved from semi-starvation and the crew from threatened mutiny.

Eighty-three barrels of oil lay cooling off and shrinking in the casks when the head was at last cast off and allowed to sink in the clear water of the harbor. The body had been cut away long before, after being stripped of all its blubber and much of its tainting meat, the latter going ashore in the native canoes for a mighty feast. Now, while the crew cleaned ship and washed down, the body and head of their victim lay some four fathoms under them, swarmed over by devouring fishes and swelling steadily with the gases of decomposition.

By the time the supplies of fresh meat had been devoured, the carcass lifted, a bloated stench to the nostrils, and drifted ashore. Over it swarmed the natives, eagerly cutting away more and more of the over-ripe flesh to eat it greedily in spite of the horrible odor.

"It's time we were out of here," grinned Captain Chase to his mates, who were wrinkling their noses at the scent from the sand spit where the carcass lay in the wash. "Chief Leli has promised me my pick of his boys, since we halted the smallpox epidemic and brought them food in plenty."

"Has he told you about that secret whale way?" asked Trueman greedily, his eyes shining.

"Not yet, but I'm hoping he will by the time we come back next year. By that time he'll have had a chance to make sure that those inoculations worked."

THEY took their anchor reluctantly, spurred on only by the fact that every night the flares of trying out were red on the northern horizon, and finally got under weigh, decks cluttered with live pigs in crates and two or three tons of cocoanuts, breadfruit and plantains. Water casks had been freshly filled at the nearby river, and all was in readiness for a long stay on the grounds.

Heading northward on a long tack, they sighted a whale boat under sail and luffed up to cut across its bow as Chase made out the huge W in its upper corner. That letter was a Wing marker, helpful in picking up the boats hunting near the fleet, and the great A under it proclaimed that this was an Albatross boat.

But the boat seemed intent on evading them. Instead of holding to its course it veered sharply. Captain Chase lifted a spyglass to study the occupants. Suddenly he ducked for his cabin to come up holding a rifle. His face was stern as he jerked the weapon to his shoulder and sent a bullet skipping across the waves just ahead of the hurrying boat.

Instantly there was excitement in the smaller craft. Brown figures gesticulated wildly. The rifle barked again. The second bullet splashed nearer, barely missing the long steering oar.

The boat whipped about before he could thrust in another shell and slid toward the bark. Scowling brown faces were lifted as the boat finally luffed up under the ship's counter.

"What's this?" demanded Chase sternly, his rifle in evidence. "Where's your officer?" For there was no sign of a white man with the four frightened natives blinking at him. "We sick," said the sullen oarsman, putting a hand to his belly, his eyes lowering.

"But Captain Kenyon would never send sick men off alone in a boat. What's the meaning of this?"

"Others sick," waving at the three. "Me not sick much. I take home men. Ship too busy killin' whale."

"Come aboard here. Let's see what's the matter with them."

The face became more furtive, the eyes even more evasive.

"Bad sickness. You catch."

He moved his oar hopefully but the ringing command killed his last lingering hope.

"You come aboard here. I'll take a chance on catching whatever it is. It looks to me like homesickness. I'm afraid you're not the ones to die of it."

Dumbfounded, the men stared at him with terrified eyes. Obediently they came slowly up the dropped ladder.

Chase examined the first one swiftly, feeling for pulse and fever, looking at tongue and throat.

"Just homesickness," he nodded grimly, "as I feared. But it might have been fatal to somebody, eh? Mister Trueman, tow the boat astern, after getting the last man aboard. This looks serious."

The natives wilted at that and poured out what he felt sure was but a partial confession. Captain Kenyon had taken them against their will as they were intent on their fishing for starving relatives and neighbors. He had worked them hard, fed them poorly, abused them greatly. Their lacerated backs bore testimony to their beatings. Kenyon had lived up to the prevailing custom among whaling masters in their dealings with natives.

"So run away. Take boat," the evasive spokesman continued.

Captain Chase looked him in the eye with a severe frown. He knew Amos Kenyon too well to believe that he had left his boats unguarded so that disgruntled natives might steal one and escape.

"Where is your officer and the other oarsman?" he demanded sharply.

One of the renegades moaned in terror at what he considered in his simplicity to be a supernatural understanding of their crime.

"You have killed them and thrown them overboard," Chase accused sharply.

Terrified denials flowed from trembling lips, but he knew that he had guessed the truth. He turned to Trueman.

"They're deserters at least, probably murderers. We've got to take them back to Cap'n Kenyon. Put them in irons."

The native members of the Petrel crew crowded around the prisoners. The atmosphere of joy that had pervaded the bark since the taking of the whale was suddenly changed to gloom. The white members of the crew began to look upon their jolly and lighthearted comrades as potential killers. Under their surface joy and gaiety lurked a viciousness the ready smiles concealed.

The natives, on the other hand, were angry over the tales the prisoners told of the treatment they had received. Captain Kenyon had been adamant in the face of their entreaties to be left on the island to fish for their sick. From the moment of seizure he had made slaves of them, lashed them when they did not jump at command, accepted their bewilderment at strange names and duties as refusal to comply, and lashed all the more.

Captain Chase listened grimly as his own natives explained the situation. To them the renegades were justified in whatever they had done to win to freedom, since the initial fault lay with their white captors. Although he was forced to admit to himself that they were right in their claims, he dared not set the prisoners free, as they requested, nor promise not to return them to Kenyon. According to the custom of the times he would be derelict in his own duty if he complied. Much as he condoned them for striking for freedom, he must uphold the white man's standards.

He knew all too well what Kenyon's reaction would be. Bred in the harsh school of a brutal whaler himself, he would be even more brutal in his treatment of the renegades. Nothing but death stared them in the face and that death probably by flogging, unless Chase could intercede for them.

HE found the Albatross hove to with the stinking carcasses of two whales lashed to her side as she rolled and heaved in the swell.

"So you picked up my boat?" roared Captain Kenyon, clinging to the futtock shrouds with a great arm. "Well, set 'em aboard. That second whale's softenin' already and the first one ain't cut in yet. We'll be lucky if we can get 'em cleaned with all hands at it."

Then he allowed a triumphant grin to spread across his face. "How you doin', Cap'n Chase? Get any hands at Tali Mahi?"

"Enough and to spare, and a whale while we waited. Eighty-three barrels."

Kenyon guffawed loudly.

"Do you hear that, men?" he bellowed. "They think they're racin' with us and they've eighty-three barrels o' oil aboard. Do you know what I've got, Cap'n Chase? Four hundred barrels topped off and fifty coolin', to say nothin' o' these two whales alongside."

Chase could not keep the hint of scorn from his voice. "And a first class case of mutiny to deal with, if I'm not mistaken. I picked up your boat as it was making for the island. Only four natives aboard."

He read the consternation in that staring face. The dark throat whiskers crushed against the shirt front as that jaw dropped in disbelief, giving the shaven portion of the face unusual length and a greenish pallor under the tan.

"But where's Mister Macomber and Nate Dring?"

"That's something we'll have to find out. My guess is that they're murdered and thrown overboard."

Flashy blades halted in mid air. Laboring bodies turned to statues. And the murmur of an angry undertone floated over the water from the weary workers.

"A pity it warn't Kenyon they got," called a shrill falsetto above that murmur. It was plainly a disguised voice, but it was full of meaning.

"Who said that?" roared Kenyon, turning upon them.

Nobody answered. Pleading eyes begged in vain for mercy as they centered on that stern face.

"Speak up, or I'll cut your rations in half until somebody does. I'll have that mutinous rascal triced up and flogged, or your empty guts'll stick to your backbones. Come on, who said it?"

Faces blanched in the awed silence. The dread of still further abuse was so strong that the men aboard the idling Petrel could sense it across the intervening stretch of water.

"They're already hard worked and none too well fed," suggested his mate placatingly.

"Stow your lip until it's asked for," snapped Kenyon. "Cookie?" Then, as the filthy cook looked up from where he had been waiting for some of the whale meat to cook for dinner: "Half rations for 'em until further notice."

"But the meat'll only go bad," protested the cook, who could understand short rations if they saved the company money.

"You heard me. you insolent whelp," advancing on him with swinging lists. "Give 'em no meat and half their ration of bread."

The quailing cook started to back toward his galley, fearful. But his efforts to protect his anatomy by use of the pan were futile. Kenyon seized him by one ear, twisted him around expertly, and planted a vicious kick on his rump, sending him sprawling.

"That's the way I handle 'em, Cap'n Chase," he roared. "Now send them boys aboard and I'll have the truth out of 'em—as soon as we get this blubber aboard and to cookin'."

Chase surveyed him, eye to eye, across the heaving water as their barks idled, aback and drifting apart as the whales held the Albatross by their drag in the water and the Petrel slid out from the other's lee to catch the force of the gentle wind.

"I think this is a matter for a gam, Cap'n Kenyon," he called.

"Gam nothin'! They're my mine. Send ‘em aboard. I'll put ‘em to work at the cuttin' in—and take care of 'em afterward, when they won't be so hard to replace. Over with 'em."

"It's a gammin' matter," insisted Chase stubbornly. "Come aboard here and let's settle it."

"And leave these shirkin' fools to let loose the whales and run for it, while I palaver over four stinkin' niggers? Nothin' o' the sort! Send 'em aboard and have an end to this."

Chase shook his head. "This is a matter of company policy. It calls for a gam between the pair of us. Your officers can be trusted to carry on."

"Damn you, Burdie Chase," roared Kenyon, forgetting in his anger the courtesy to a skipper that discipline demanded in the presence of their men, "I'll break you for this when I'm in command of the fleet. If you know what's good for you, you'll send them niggers aboard."

"That's just the point," called Chase. "They're not niggers; they're free men."

"Drop my gig," roared Kenyon. "I'll show the namby pamby idiot who's boss of them dirty murderers."

HE came storming up the Petrel's jacob's ladder and onto the deck, his face purple. Chase fronted him with an equal show of determination, his own eyes hard and cold.

"Give me my men," gritted Kenyon.

Chase stepped near to him and dropped his voice so that none of their men could hear.

"Listen," he snapped, "you might scare those poor devils aboard your ship with your loud bluster, but you're not scaring me. Calm down before the men and act like a man, even if you do feel like a spoiled brat. Come on into the cabin and let's have this out." For a long minute they stood there breast to breast, eyes flashing, tensed bodies ready for combat.

"You strike first, if you want war," urged Chase under his breath. "I want no other excuse for pounding your carcass limp and tumbling it back into your boat. Go ahead and strike just once and I will."

Kenyon measured the smaller figure, aware that there was concealed strength under those shirt-sleeved arms, agility in that nimble figure.

Luckily for his predicament, somebody cried at that instant, "Sail hard aboard. Looks like the Canvasback."

It was another of the Wing vessels, named as were all the others for a nautical bird. The tenseness slackened. A crafty look came into Kenyon's eyes.

"It's the Canvasback, sure enough," he called eagerly. "Have Cap'n Tripp aboard to settle this."

The older brig luffed up and her white haired master came aboard to the swing of quick oars in response to the signal requesting his presence. Sprawled on the horse-hair sofa built into the cabin of the Petrel, he listened with a bird-like cocking of his small head to first one indignant narrator and then the other.

"This is a very serious matter," he said at last, blinking. "The original crime's bad enough, goodness knows, for murder's always a nasty crime. But the spectacle of two ship-masters wrangling like children over anything is worse than the cause." He paused. "You're wrong, Kenyon," exploded the judge suddenly. Then he nodded shortly and sharply a score of times while Kenyon reddened. "Yes, you're wrong. Disgraceful in a man of your standing! Brawlin' and bellowin' like a mad bull!"

Chase gasped, for he had expected the older captain to stick by the older idea of nautical justice. A slow grin began to spread across his face at the evident promise that there was a warm heart under Tripp's tight jacket.

"But only in the brawling," Tripp burst out again. "Chase, you're much worse. You ought to know that a skipper has sole right over his own men and gear. That boat belongs to the Albatross. So do the men mannin' her. You'd no right to refuse to set 'em aboard when requested. They're Kenyon's to do with as he sees fit."

"But don't you see," protested Chase, "that we've got to establish a company policy about the handling of these natives? Soon we'll be unable to ship crews from among 'em. They're better and cheaper than Yankees and we need 'em. Unless we earn their respect—"

"That's just it, just it," interrupted the nodding Tripp. "Respect. That's what we must have, respect and discipline. Unless we have it," accusingly, looking from one to the other, "for fellow captains, how can we expect ignorant natives to have it? Punishment brings respect. Fear's all they know. They'll bite the kind hand, but don't dare to snap at the whip hand."

"Yet they killed on the Albatross. I've had no trouble here."

"Which proves what he's sayin'," insisted Kenyon. "Macomber, who had charge of that boat, was a softie. So was that fool Nate Dring who was along with him as boatsteerer. You don't find rats like them murderin' men like me."

"Because you don't venture into the boats with them where they could get at you. They'd kill you in a minute if they got the chance."

"Gentlemen, I have given my decision," said Tripp, rising and starting up the companion. "I shall write a full account of this to our owners—including the disposition made of the men, Cap'n Chase. As arbitrator I command you to hand them over to Cap'n Kenyon."

Chase threw up his hands hopelessly. "You win for the present, Kenyon," he admitted. "Once back in Bedford I'll have my say about it, though. This abuse of natives has got to stop."

"What you say when you get back to Bedford isn't likely to count very much," grinned Kenyon, "unless you figure on fillin' your casks with the soft soap you bubble out of your own mouth. Come on, Cap'n Tripp, let's you an' me get out of here before we have softenin' of the gizzard along with him."

There was consternation on deck when Kenyon sternly ordered the prisoners into the boat and started towing the craft behind his gig back toward the Albatross. One of the men in irons stood up in the pitching boat and seemed to be making a farewell oration to his neighbors on the Petrel. His words were received in stony silence as the solemn faced islanders clung to the rigging.

Suddenly, at a ringing cry of defiance from the standing man, the others leaped to their feet from where they had been drooped disconsolately on the thwarts, their hearts heavier than their shackles.

"Sit down, you fools, or you'll be pitched overboard to drown," screamed Kenyon. "You can't swim with them irons on you. I—"

His jeers seemed to stiffen their determination. As one they lifted their heads. Each put a foot upon the gunnel lifting clanking chains. As a high wail lifted from them and turned into a mournful chant, they exchanged glances, nodded in unison, and went overboard in a clean united dive. The clank of their heavy chains echoed, their dark bodies were visible fighting down, down, down through the brine until the blotch blended in wavering outlines with the dark depths and was lost to view.

Sick at what he had witnessed, Chase turned away. His own native workers, after echoing the dismal chant of the suicides, stared at Chase sullenly. Fear lurked in their pathetic eyes as they watched master and mates moving about the ship.

A PALL of suspicion and terror obsessed the ship as the Petrel bore away, leaving Kenyon's wretches to his abuse. Mutiny threatened in the form of a race war, for the whites in the crew were fearful of the murderous instinct that had flared in their less fortunate fellows, even as the native workers were afraid that they, too, were headed for abuse.

Only the sighting of whales late the next day brought an end to the glooms. The waist boat made fast and killed, although the others all drew or were forced to cut. To ease the tension and insure good spirits, Chase served a double round of grog.

The hot liquor gave the men fresh spirits and a brighter outlook. The labor of cutting in and trying out gave little time for brooding. Everything went along so smoothly and so free from unnecessary brawling that the timid natives took courage. Quick to respond to kindness and quick to forget sorrow and pain, they were soon laughing and joking and singing again. When the boiling down was finished five days later and the decks cleaned again. they strummed happily on their native ukeleles. fraternizing once more in perfect accord.

Then another shoal of whales arrived and they put over the boats with every man straining to be in at the kill. In the midst of the excitement, Chase looked up to see the Albatross hard aboard, her boats ready to drop. Soon the sea was dotted with idling whales, blowing their spray in tiny founts and jets, with laboring boats gingerly approaching the lazy monsters, or backing swiftly away after a flung harpoon had made contact.

Every boat was far away when a big whale slowly lifted to the surface between the rapidly closing barks and snorted an exhalation of his pent up breath, which mingled with the sea water in his blow hole to form a fountain of spray over his sleek back.

Captain Chase glanced at the boats, towing seaward or maneuvering toward other monsters. Then he took another look at the spouting whale and at the lone boat still hanging in the davits.

"Shipkeeper," he bawled, "take over and stand by to pick up the kill farthest to windward, drift down upon the other boats and pick them up as they tow to the ship. Man the boat, boys! We're going after that baby yonder."

Even as his boat smacked the water he saw Captain Kenyon stare at them and then at the idling whale. Instantly Kenyon wheeled and raced to lower his own boat.

Since the Albatross was much nearer the monster than the Petrel, a race developed to see who would be first to dart iron into the whale.

"Give it to 'em, boys," urged Chase quietly. "Show him what a crew that knows no lashing can do before a bunch of whipped slaves. Bend them ash breezes! Pull for kind treatment aboard whaling ships. Show him men're better for bein' able to say their souls are their own. Either Kenyon or me gets the new flagship of the Wing fleet and whoever does will demand his own type of discipline in the fleet. Here's a chance to prove kindness is what you like."

The heavy boat with its load of gear fairly lifted from the water. Backs bent and arms reached in perfect unison. Onward they rushed, steadily increasing their speed.

But Kenyon was working his men, too. Snarling a constant stream of threats, he drove his laboring victims viciously. Both boats were about equally distant from the whale and closing rapidly, but the Chase boat began to gain. Tense in her stern, the skipper watched the narrowing distance with expert eye.

"Stand by to iron him, Leander," he called.

Leander's short oar clattered into the boat and the harpoon seemed to leap into the man's hands. Bracing himself swiftly, he crouched in readiness.

"Back water! Hold her or you'll ram! Stand by to back water! Now, Leander, let him have it!"

The iron sped true. It was a long cast but an accurate one. The clumsy looking wooden shaft stood upright and quivering in the mighty mass for an instant. Almost instantly the huge creature heaved forward in a startled dive.

"Fend off, you robber, we've already struck," screamed Chase, catching sight of the Kenyon boat with the harpooner poised and ready to dart iron. "This is our whale."

"It's still alive," roared Kenyon. "Dart, you idiot, dart at him! Leave the right and wrong o' the matter to me. Hurl that iron!"

The hesitating boatsteerer dared delay no longer. That snarled command seemed fairly to lift the weapon from him in a swift wide are that ended in the disappearing body of the great whale.

"Cut, you thief; we're still fast," screamed Chase. "A whale belongs to the first man to get iron into him."

"You'll never take him," jeered Kenyon. "I'll show you how it's done."

Chase was so busy swearing at him that he was late in getting a turn of line around the Sampson post. Kenyon's boat, traveling in the whale's wake, shot off ahead.

"Killer takes all," called Kenyon defiantly, as his boat picked up speed.

Too wild with anger to answer, Chase merely slowed the flight of his own line, and started his own boat in motion. Later, when the monster began to tire, he could take in hemp and pull abreast of the other boat. Then he saw that the other boat was slowly inching back to bob and wallow and veer and skip a scant five fathoms off his bow.

At a loss to understand just what Kenyon meant by the maneuver, he watched closely. Kenyon called something that was indistinguishable in the seethe of rushing water, swanking impact, and the wind of progress.

Then Chase understood. Kenyon was probing the water as his boat veered wildly back and forth in response to his shouted directions to the boatsteerer. With a savage thrusting he was searching water directly under his bows with that two-edged weapon that was kept at razor sharpness to probe the weary whale's inwards at the end of the chase.

But the whale was nearly half a mile away, driving madly. That lance was questing now for one thing only!

There came a thrum down the taut line that Chase's hand touched. His horrified eyes saw a single strand uncoiling from the tight twist, saw the severed edge, cut by that clean blade.

"Fend off from my line, you vandal," he screamed, brandishing his own lance.

Kenyon favored him with a grin of defiance and probed again, as a sea slapped over him. Chase thrust the lance back into its greased sheath and grabbed for another-harpoon. With murder in his eyes, he lifted high to heave it.

A scream of terror burst from the boatsteerer ahead as he looked back. But the Albatross boat had swept over that submerged hemp again. Kenyon, his head and shoulders buried in the brine that poured over him, was thrusting deep with that keen blade, his legs held by an oarsman. Even as Chase cleared the harpoon for the cast, the taut line parted suddenly, and their tearing speed slowed at once to drop them rapidly astern of the other boat and let the arching weapon chug harmlessly into the sea. Instantly Kenyon was standing dripping in the bow, his thumb to his nose.

For one long minute Burden Chase stood there, his mind a seething, blinding red. Then he turned and faced his men, grimly clambering aft to take the steering oar and motioning the boatsteerer back to the bow to row.

"Put us aboard the ship as fast as God A'mighty'll let you," he said in a voice so pregnant with rage that they would not believe it was their skipper speaking. "This ain't the end by a long shot. He started something that I'm goin' to finish."

WITH sail lifted to aid the rowers, they were soon hoisting aboard. Barely glancing at the scattered boats, towing away behind frightened whales, Chase glanced aloft.

"Get more sail on her," he snapped. "Shake out them reefs in the royals."

Kenyon had all but vanished over the horizon but Chase had marked the course of that towing boat. Ignoring his own boats, one of which was engaged in the tricky job of lancing a whale and trying to escape from the lash of its dying flurry, he headed grimly after Kenyon.

"Lay out the longest handled spades," he called savagely, as they finally drew near and saw Kenyon drive that lance far into the vitals of the gasping whale and then send his boat surging backward to escape the mad lunge of death. "Lay me aboard that whale of ours, helmsman. Luff her up between boat and carcass."

"Between boat and carcass, sir?" asked the abashed man at the wheel.

"You heard me. Straight between 'em."

"But there's no goin' between 'em, sir. He's closin'."

"Force your way between 'em, if you sink him."

Leaping into the bluff bow, he glowered down at the nervous Kenyon, whose smile had faded from his face.

"Fend off," snarled the master in the boat. "You'll run me down."

"I will if you don't leave my whale alone and put back to your own ship, you dirty pirate."