Help via Ko-Fi

IN presenting this complete novel, we wish to call attention to the fact that this story was published first in Germany. The present translation was made on behalf of SCIENCE WONDER QUARTERLY, the translation being done by an American, Francis Currier. This is the first English translation, and SCIENCE WONDER QUARTERLY has acquired all rights for this story in the United States.

The story was selected by the editors of the QUARTERLY because it is without doubt one of the greatest, if not the greatest, interplanetarian story published in recent years.

With complete German thoroughness, the author has not written simply a science-fiction story, but has incorporated in it the latest scientific advances in the new art of space-flying.

It may be said without fear of contradiction that the material contained in the greater part of the story has never been used by any science-fiction writer before.

While writing the story, the author has had the collaboration of practically all the German scientists who have of late come into prominence in their researches, into not only rocket flying, but space flying and astro-physics.

The scientific angles contained in this story are as accurate as the present art permits, and may be termed prophetic in many ways.

There is nothing contained in this story that might be termed fantastic, so far as the future is concemed. Sooner or later the art of navigation of outer space will catch up with the predictions contained in this unforgettable story. It is certain to become a classic of its type before many years have passed.

PREFACE

(Which may be read through or not)

WHEN the ingenious Jules Veme wrote his "Joumey to the Moon," he did not suspect how soon this problem would engage the attention of serious physicists. What he consciously treated as a fantastic utopia is to-day close to realization, and perhaps the first rocket is hissing on its way into space before this book leaves the press.

The "Shot Into Infinity" is no utopia. The technical basis of the novel rests on the results of the most modern research and physical facts, and it is nothing but the development of the practical applications of discoveries which are no longer questioned to-day.

Very often persons who undeniably possess a certain degree of judgment have asked me, with a superior and almost pitying smile, whether I seriously believe that someday people might be able to leave the earth. Once and for all let this question be answered in this place by a counter question: Why not?

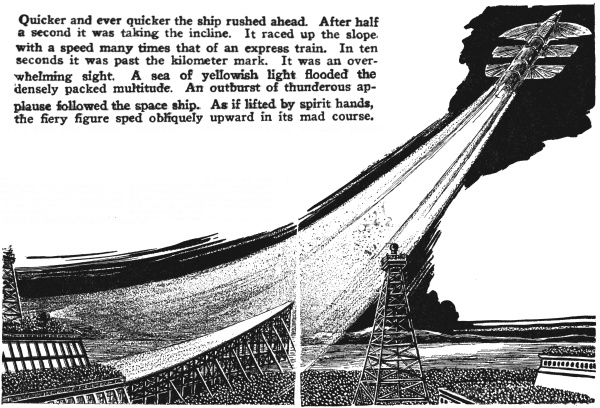

In the final analysis the possibility of all the marvels of the technology of transportation depends on brute force. When the motor was invented which afforded half a horsepower for each kilogram of its own weight there sprang into existence the airplane which hitherto had been decried as a mad fantasy and speedily a way was found to overcome the little extra problems of the designs of the wings, the propeller, and so forth. The motor which is to carry persons (or for that matter itself only) into space must actually develop more than 100 H. P. for each kilogram of its own weight, in order to be able to combat successfully the powerful attraction of the earth. But unless all appearances are deceptive, this motor has already been invented or at least is en route to discovery.

In particular two scientists of world fame have been working at this problem for years—Prof. Hermann Oberth, a German, of Mediasch, and Prof. Robert H. Goddard, an American, of Worcester, Massachusetts—and both have solved it, though for the present only theoretically, by means of the rocket motor. Once this mode of propulsion (which is not dependent on any atmospheric resistance and develops its full efficiency only in a vacuum) has maintained itself in practice, then the "space ship" itself becomes an alluring but absolutely solvable problem for skilled constructors. For what the uninitiated regard as unconquerable factors, the fearful cold in space, the lack of air to breathe, the absolute absence of weight, are not at all real hindrances, and we may confidently assert that the engineers of 1930-40 will be able to make vigorous assaults on these problems with air generators and heat insulators.

To both of these gentlemen I herewith express my sincere admiration and my hearty thanks for their co-operation.

Of all the investigators who devoted themselves to the problem of the navigation of space, at present the American Professor Goddard seems to be the most successful; for if the last reports from Worcester are accurate, in the near future the first Goddard experimental rocket (without passengers) will ascend to the moon, and mankind is at the eve of a veritable new epoch in world history.

OTTO WILLI GAIL.

CHAPTER I

Mysterious Happenings

IN one of the ravines which transverse the southern portion of the Carpathians in their steep descent to the Wallachian plain—between the romantic deeply-cut valley of the Oltu River and the pass of Predeal, over which the express trains thunder on the way from Czernowitz to Bucharest—lies the lonely monastery of Valeni.

A bad, almost untravelled road branches off from the highway above the village of Suicii and winds between darkly-wooded crags in its easy ascent to the old walls of the monastery. Long forgotten and a prey to the moss and vines, the monastery clings to the mountainside, a reminder of times long past when the orthodox Carpathian monasteries changed into stubborn castles and stout defences against encroaching Islam, and the spiritual lords were no less practiced in weapons than the bailiffs and dukes of Swabian fortresses.

* * *

It is now more than a year and a half since the inhabitants of Suicii were surprised by an unexpected visit. The strangers arrived with a line of trucks, no one knowing whence they came or what they wanted. Then wagons came almost daily from the Oltu valley, laden with tools and building material, chests, furniture, and mysterious machinery.

Curiously, yet shyly, the villagers watched, as gradually a little colony grew in the valley of Valeni—as electricity and radio made their appearance. But none of the strangers understood Roumanian or Hungarian, and so the purpose of the new colony remained a riddle. Even the magistrate in Calimanesti knew only that the people were from Little Russia and were workers of the oil magnate Romano Vacarescu, to whom the forests about Suicii belonged, and that they were to build some dwelling houses near the monastery of Valeni.

At length the excited minds were eased; people became accustomed to the increase in population, and continued to till the cornfields and to drink the inevitable plum brandy. But one day curiosity was newly aroused by the story of a shepherd who came from Magura Cozia.

On the open plateau between Cozia and the damp valley of the upper Arges River strange buildings were being erected. Heavy concrete pillars, surrounding a circular open space, rose high in the air. Within was being built a peculiar structure, about which nobody could form a clear idea. Some claimed that it was the dome of a fortified tower, others asserted that a mighty memorial monument was being erected there, and extremely clever persons could tell (from some certain source or other) about an airport which promised Suicii greater economic importance.

But as the construction proceeded, the entire plateau was surrounded with a high fence and the entrances were carefully guarded. Thus the imaginations of the natives had free run, and soon the most impossible stories about the mysterious structure were current.

There was also great activity within the ancient walls of Valeni. Heavy hammer strokes thundered from the subterranean cells, machines hummed day and night, and thick clouds of smoke poured from the newly erected chimney. In the abandoned monastery yard rose heaps of coal; oil tanks and steel cylinders stood in long rows by the walls; and thick bundles of electric wire ran from the monastery, some across to the plateau and others to the dwellings of the workers.

At night, when the Roumanian mountaineers were sleeping in their sheepskins on the wooden porches of their mud huts, a bright illumination shone from the old walls and cast trembling reflections on the black mountain side.

A Meeting in the Monastery

AN impressive automobile sped through the winding valley of the Oltu. The narrow foot of the valley, between the closely crowding Carpathians, gives barely room enough for the road, the river, and the single track railway which runs obliquely through the mountains from Hermanstadt to Slatina. Fairly often, in fact, the highway crosses the rails and traverses the Oltu River on shaky bridges. Coming from Ramnicul Valcea ("Garmisch," as the people of Bucharest term it), the car took the sharp curves before Calimanesti at undiminished speed, climbed with a rattle the ridges of Berislavesti, and crossed Suicii in its mad course. The natives humbly knelt: they recognized the green car of the man who owned the oil wells of Ploesti and countless square kilometers of Carpathian forest.

By speculation on a grand scale the insignificant little Roumanian had in a few decades amassed a fortune reckoned among the greatest in the country. Oil and wood had been his motto: oil for export, bringing him good foreign money, and wood for the wide treeless plains of Wallachia.

The car stopped squarely before the monastery.

"Where is Mr. Suchinow?" the passenger demanded of the young man who promptly opened the door of the car. He spoke French, the language of an aristocrat of Bucharest.

"Monsieur Suchinow is waiting for you down at the office."

"Too bad! Call for me again in an hour and a half," he ordered the chauffeur, and then he descended into the dark cells of the monastery.

In the narrow corridor leading to the office, a slender man came to meet the visitor.

"You are punctual, Monsieur Vacarescu. How was the trip across the mountains?"

"No circumlocutions, if you please, Monsieur Suchinow! I do not enjoy idle conversation when it is a matter of business."

The reproved man remained silent. He knew the peculiarities of the fat little financier and yielded to them.

The two men entered the office, a comfortably furnished room, the thick walls of which muffled the noise of the workshops; the incessant hum of the high frequency generators operating close-by was noticeable only because of a slight trembling of the walls and furniture.

"How far along are you!" asked Vacarescu, curtly, sinking back into a chair with a sigh.

"Finished!" replied Suchinow, still more curtly. On his face, which was strangely dotted with green spots, lurked the shadow of a contemptuous smile.

"Finished except for . . . . ?"

"Except for nothing!"

"Do you really mean that the rocket can now be released at any moment?"

"Tomorrow evening at nine twenty-five sharp (Central European time) it must be released, unless I want to loaf around thirteen days more until the next quadrature1 of the moon.

1: The moon is in quadrature when a line drawn from the earth to the sun to the moon makes an angle of 90 degrees. Suchinow evidently did not want to travel directly toward or away from the sun.—Editor.

The fat financier seemed to have had his breath taken away. His surprisingly narrow hooked nose, which seemed entirely out of place on his fat broad face, trembled as though threatening to fall off.

"And I? And our company?" he snorted.

"Yes, you must certainly hasten, if the Transylvania Company is not to get ahead of you at the last moment!" remarked the slender man pleasantly.

"You have a nerve!" exploded Vacarescu angrily.

"No idle conversation, if you please, Monsieur Vacarescu! It is a question of business. We can be finished in a few minutes. The contracts are ready. Have you deposited the money?"

"I am going to protect myself. First, this matter of the Budapest account does not suit me. If the rocket does not return, I lose my money for nothing. Now tell me, who is to steer the thing?"

"Skoryna—you know very well."

"Do you really expect me to settle a fortune on this untried lad with the peaches and cream complexion?"

"Sir," replied Suchinow sharply, "you must certainly entrust all these arrangements to me, whether for good or ill."

"For my money I can probably demand some guarantee, too!" said the irritated Vacarescu. "Does not Skoryna guarantee matters with his life? What further guarantee do you wish ?"

"Bah! a valuable life for twenty thousand English pounds!" jested the financier maliciously. A shadow crossed the green-spotted face of the Russian.

"Can one balance a human life with money, Monsieur Vacarescu? Even the life of an-an engineer like Skoryna? I beg of you to regard the discussion of this point as closed."

"At least, your preparations have remained secret?"

"Certainly, so far as is humanly possible. Of course the press notices and the information for the Lick and Babelsberg observatories are already prepared. The radio announcements are to be sent out immediately after the signing of the papers."

After a short pause Suchinow suddenly asked:

"Why do you set such store by absolute secrecy?" He looked slyly up at the man opposite.

"I should not like to have this German—what is his name, anyway?—"

"August Korf."

"Right! I do not want this Korf to take a hand in our game. I trust he knows nothing about it."

"How should he? After all, what harm would it do? He has not yet finished his first experiments, and he could hardly make up my head start. By the time he can think of competing with us, we shall long since have set the world in an uproar and your foundation will be established solidly. Do you doubt that?"

Vacarescu thoughtfully twirled his watch-chain.

"I cannot help thinking that this Swabian will somehow upset our calculations."

The inventor grew pale. Anxiously he examined the expression of the financier, and he nervously drummed on the arm of his chair.

"How so?" he asked with forced indifference.

"Do not underestimate this rival! You know that he invented the rocket at about the same time as yourself; he knows the dynamic cartridge; and lately he has been asserting that he can attain twice as high a repulsion-speed by using liquid explosives. Some day this man will come into the open with some startling revelations, and then you and I are in the soup."

At these words, offering no interpretation but the speculator's anxiety about his investment of capital, the tension in Suchinow's face was released.

"I see perfectly well, Monsieur Vacarescu," he said calmly, "that you have so little confidence in me and my—in Skoryna, that it is doubtless best for us to break our relation and for the Transsylvania Company. . . . "

"For Heaven's sake!" interrupted Varcarescu, almost screaming at him. "You shall have your deposit! But the Lord help you, if we fail!"

With a smile bordering on pity Suchinow lifted the telephone receiver:

"Connect Monsieur Vacarescu with the Bucharest Bank of Roumania—yes, the president himself—very well, then call up here."

Then he opened the door of a little cabinet built in the wall, took out some papers, and spread them over the table.

"Here, Monsieur Vacarescu, is the transfer of license, here is my appointment as general director of the Transcosmos Stock Company, here is the sealed envelope with Skoryna's will of the twenty thousand pounds, due from the Budapest account in the case of his death, likewise the statement of your message to the Bank of Roumania (which you yourself will telephone in a few minutes)—and here is ink!"

CHAPTER II

Uncle Sam

A SUNNY day of late summer was ending. The light wind which at noon had ruffled the surface of Lake Constance was ceasing, and the last dying waves were splashing on the shore.

Far out on the lake shone in the rays of the evening sun the dazzling white sails of a little yacht. It seemed motionless. The main boom swung back and forth at random, the foresail hung down limp, and the tiny current of air could not even keep up the pennant at the mast-head.

The steersman attentively viewed the horizon and the little white clouds that swam over the Alps, glowing in the sun.

"After sundown there may be a breeze again," he said to his companion; "we now can only choose between waiting and rowing. What do you think, Uncle Sam?"

"I think," replied the latter, "that we have time to wait. If the evening breeze fails us, we have at worst lost a couple of hours—or gained them, my boy! Such a splendid evening calls for enjoyment."

The helmsman rose, secured the tiller and sheet, and made himself comfortable on the forward deck. "Just see what a festive cloak the mountains have put on to receive me. Truly, old Zugspitze yonder is blushing for joy that old Sam has returned. Lad, how beautiful our home is!"

"It is true, Uncle. But can all this still impress you, a man who has hunted in the jungles, meditated beside the Ganges, and frozen in Tibet. Can our poor little Zugspitze still seem striking to you who have seen Mount Everest rise into space?"

Uncle Sam slowly and thoughtfully filled and lighted one of his pipes, which he always carried with him in large numbers, projecting from all his coat pockets. Then he inhaled deeply, so that there was a gurgling within the beloved pipe; he blew a mighty cloud of smoke into the air and said, as soon as this busy occupation gave him time:

"Everywhere in the world there are beautiful and noble things, Gus. Yet it is always a matter of the relation in which you stand to them. See, this Everest you spoke of: you look at it and at the same time you realize that it is the highest point on earth—it is unfortunate that this is known—you reflect about the nine thousand meters, reckon and consider—puzzle your memory over all the trifles you had in school concerning this marvel of a mountain—and by the time you have successfully digested all this, you have travelled on. And you have not even become acquainted with the proud king who sits at his record height and with cool graciousness waves farewell to you from afar.

"But our Alpine range here, with yonder the abrupt descent of Zugspitze and across the lake Pfänderhügelchen: these are no record-seekers, only dear old friends whom I well know. Isn't that so, old fellows? You still remember your old Samuel Finkle!"

In youthful exuberance the man of fifty waved his hat in greeting to the mountains of his home.

"See," he went on, "it is so with everything. There is nothing in the world of which one can absolutely say that it is good, it is beautiful. It is always a question of good and beautiful for whom—that is it."

Reflectively he spat into the water in a great arc.

"As long as your dear sister was still alive, I never thought of leaving our Alps. But when she fell at the Wettersteinwand—well, you know all about it—when we had buried her, then I cursed the mountains; I could no longer bear to look at them, and I went to India to the jungles. But that is long ago, and I have pardoned the mountains for not watching over her better."

Then both lay silent, close together on the slightly rocking deck, listening to the lapping of the tiny waves on the side of the boat and letting their glances sweep into the greyish blue infinity.

August Korf, the famous chief engineer of the national airport in Friederichshafen, pressed his uncle's hand sympathetically. In reality the little man beside him, all dried up by the tropic sun, was not his uncle but his brother-in-law, and Dr. Samuel Finkle owed his position as "uncle" only to their noticeable difference in age.

"Uncle Sam," said Korf after a while, "better dead than—than lost!"

"What! You, also?" In surprise the old traveller looked up.

"No, no, Uncle! It was only an idea!" protested Korf.

A Question of Astronomy

THE sun had set. The sky was growing darker, and in the southeast Mars already glowed with its reddish light. Venus, the evening star, pierced the golden yellow glow of the western horizon; gradually the two Dippers lit their torches, and the "W" of Cassiopeia rivalled in splendor the sparkling starry cross of the Swan.

"Gone and carried away!" the engineer broke the stillness. "The evening breeze is not yet stirring!"

"That's the mischief of it!" said Uncle Sam in comical excitement. "You claim to conquer the universe and you cannot even conjure up a little bit of ridiculous terrestrial wind, which we need for the trip home."

Korf smiled. "Perhaps it is easier to rule space, the absolute nothingness, with its rigid laws, than the 'ridiculous terrestrial wind,' which is dependent on a thousand influences. In space it is calculation alone that conquers."

"Are you so sure of this? Do you think that chance is entirely excluded in the universe?"

"What is chance? Is there really chance, or is it not' 111 the last analysis a phenomenon the laws of which at present still escape our knowledge? Surely it can safely be assumed that the possibility of uncalculable phenomena is reduced to a minimum, so that (strange as it may seem) human knowledge controls space better than it does numerous phenomena on our little earth."

"But this minimum may suffice to shatter all your plans." Dr. Finkle energetically drew at his pipe. "How closely defined are the limits of our life! A change in temperature of a few degrees is sufficient to cause death. On the tiny layer between the glowing center of the earth and heatless nothingness of space live man, beast, and plant; it is merely chance which has left exactly this space for the possibility of life. It is a trifling tact on which our life is based, and only an equally trifling impulse is needed (for which your 'minimum' easily leaves room enough), in order to destroy it—to blow out with a breath an insignificant little human being who rashly seeks to leave Mother Earth."

"Granted, Uncle Sam! Just such an opinion was once expressed by the city council of Nuremberg, when the first railroad to Fürth was to be built, yet today the express trains speed from Paris to Stamboul.

"Shall I stop because of this minimum in the possibilities of failure? Shall I destroy my invention, because it perhaps is not yet perfect? Shall I withhold from mankind a considerable advance in knowledge, because it may perhaps lead to disappointment?"

"Gus, you misunderstand me. Believe me, I admire you and your work, which I hope you will soon show me. But I doubt whether this constant advance in external knowledge is a blessing for mankind. Do you believe that motorists and aviators of the twentieth century are happier than the subjects of Frederick the Great, for whom a joumey from Brandenburg to Cassel was an event prepared months in advance—a real experience? Who has such experiences today? Will not external knowledge celebrate its triumph at the cost of inner knowledge—and then shall we have gained anything? I dread outspreading civilization, if it destroys concentrated culture."

Korf did not reply, and for a while old Sam was also silent, knocking the ashes from his pipe on the side oi the boat.

"Do you believe that man-like beings inhabit the stars?" he then asked very suddenly.

"Hardly; that is, I do not know. On the seven known planets conditions prevail which exclude the existence of living albuminous cells. The only planet whose temperature and atmosphere offer any possibility of vegetation and accordingly of life is Venus. But all investigations and observations indicate that no rational beings live even there. And of the planetary systems of the so-called fixed stars we know nothing or practically nothing."

"I will tell you something, Gus. You engineers and scientists are extremely clever persons, but somewhere in each of your brains is a gap. You can calculate until a person gets dazed, but thinking is something that you cannot do."

"You are exceedingly complimentary, dear Uncle!" said Korf with a laugh.

"Well, please give me a single valid reason— valid, you understand—why among all the millions of worlds the little clump we call earth should alone be selected to have the heritage of life and reason! Well?"

Samuel Finkle did not seem to expect an answer. Rolling over on his side, he took from his trousers pocket a new matchbox, twirling it in his lingers, which resulted in splitting a joint of the box. He continued his remarks:

"It is megalomania to believe that! At least now, after science has robbed our earth of its ancient position as the motionless center of the universe and has assigned it the modest place of a planet circling about the sun."

"Of course you do not venture to disturb the eminent position of the sun, do you?" said Korf, amused by his uncle's zeal.

"Of course the sun must revolve about some central star or other, in my opinion Sirius, and the latter again about something more central, and so forth."

"Then you do grant a certain order of rank, Uncle. Central, more central, still more central, most central of all. . . ."

"With you mathematicians a fellow cannot speak a sensible word. Are you trying to make a tool of old Sam?"

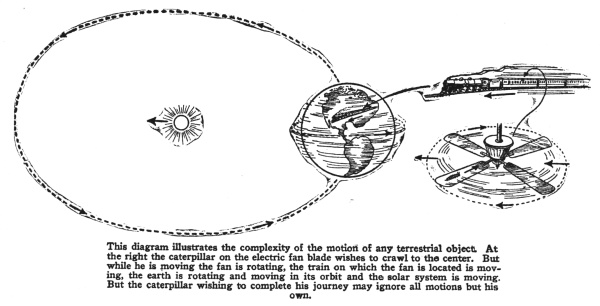

"No, Uncle." Korf became serious. "But one thing is certain: the earth does not revolve around the sun, any more than the moon revolves around the earth. It only seems so."

"It only seems so?" Uncle Sam's pipe had almost fallen from his mouth in his surprise. "Do you know, Gus, things cannot so easily amaze an old globe trotter like me, but I am exceedingly amazed that you should mock your good uncle this way!"

Having spoken, he rolled over on his side, evidently hurt and firmly resolved to regard the conversation as closed.

"Just think a bit, Uncle; you can do it better than I! Where would your theory be with regard to the equality of the stars and consequently the rational beings living on them, if you allow the sun the rank of a central star? I only want to confirm and supplement your theory. The universe is more democratic than you think."

Already old Sam broke his resolution and condescended to call back over his shoulder: "What the devil does the earth revolve around, if not the sun? Are you accusing old Kepler of lying?"

"Around a point, Uncle; around the same point as the sun itself, around the common center of gravity, which on account of the immense mass of the sun lies so near its center that we may well pardon this slight error and calmly pass over it. Won't you be kind enough to turn back again?"

"Then I am right, am I not?" said Sam, making a half-turn.

"Surely, Uncle! On other heavenly bodies there may well be rational beings. But as long as it is not proved, we must leave the question to philosophers and novelists. But look! The evening breeze is coming!"

Quickly he released the tiller and sheet. On the greenish black surface of the lake appeared bright trembling streaks, coming nearer and nearer, precursors of the expected breeze. In a few seconds it reached the yacht, inflating the canvas and making the loosely flapping jib crack like a whip.

"There, Uncle Sam, this will be a speedy return trip. Look out, I am going to tack!"

The bow cut through the waves, casting up the spray; the wind sang in the shrouds; before the lake sank into complete darkness, the yacht was rocking at its buoy.

Bluff or Reality?

IN the pure sea air of California, at a considerable l height' above sea level, stands the great Lick astronomical observatory enjoying, more than any other, especially favorable conditions for the observation of the northern sky. The dustless air permits the use of such great magnification that the aged observer, Nielson, chose as the special field of his researches the exact study of the surface of the moon. Nielson was also considered the chief authority in the observation of the little planet Mercury, visible only in the uncertain half-light of evening or morning.

On the evening of the sixth of September the aged scientist was startled out of his calm and peaceful contemplation of the magnificent surroundings by an amazing radiogram. Carefully he studied the dispatch, uncertain whether he should regard the message as serious or as a poor jest.

"What do you think of that?" he asked his assistant.

"Suchinow—Suchinow!" replied the latter. "That must be the Russian who caused so much excitement by his work on the conquering of space by means of rocket propulsion. Do you remember, sir? He claimed that he had solved the problem and that he could actually carry out his plans, as soon as he had at his disposal a propulsion material with a latent chemical energy of about 60,000 calories per kilogram. When his experiments at that time always failed, the matter was regarded as mere fantasy. Perhaps he has now really found a sufficient source of energy."

Shaking his head, the old astronomer reread the telegram:

"September 7, 9.25 P.M. Central European Time, Suchinow moon rocket leaves 45° 16' 40" N. Lat., 24° 34' 30" E. Long., Greenwich. Observations please, Transcosmos, Bucharest."

"According to our local time that would be tomorrow afternoon at one," said the assistant. "By day we can hardly see much."

"Still less at night, if the rocket is not suf?ciently illuminated," answered Nielson. "Do you really believe it at all?"

"It is not impossible. If the Russian has an energy accumulator of sufficient capacity, the matter is hardly to be doubted; spatial navigation has thus far failed only on this one account."

"Man, do not tempt the gods!" murmured the aged astronomer into his grey beard. Then he said aloud: "Make the necessary preparations and have the observatory ready at any rate by six o'clock tomorrow afternoon. Before that we can hardly expect to make an observation."

In spite of his great doubt of the success of the enterprise just announced, Nielson spent the night in feverish excitement.

"Shall I live to see it," he thought, "this marvel of man's leaving the earth and rashly peeping behind the moon?"

Then there awoke in him the interest of a scientist who had devoted a whole life to his research. At last mankind was to receive enlightenment and certainty regarding the appearance of the part of the moon which had been hidden from the earth for thousands and millions of years! The fabulous three-sevenths of the surface of the moon, about the nature of which there was no explanation but surmises and hypotheses: very plausible, indeed, but mere hypotheses after all!

The apparently inexplicable mystery was about to be solved, and he—Nielson—need not take the question unanswered to his grave.

That night he did not close his eyes. In excitement he ran back and forth between his study and the giant telescope in the dome. Then he went down the steps of the tower and walked about in the open.

The moon shone in its first quarter through the pure sea air. It seemed to be laughing at the stir which human beings were making about its hidden side.

Nielson became thoughtful. He knew very well the problem of the space ship, which years ago had been widely published in all the papers and had then sunk into oblivion, since there could be no practical solution in view of the lack of a proper fuel. Likewise he did not regard it as impossible to send a shot from the earth; but could a man withstand the fearful initial acceleration? What was the use of a space ship without an observer? The radiogram had given no information on this score. What if it were only a bad joke which he was taking as something serious?

Slowly the night went by, still more slowly the following morning. It became afternoon. Now, at this very moment, the shot was taking place, provided the news was correct. Nielson could hardly conceal his excitement any longer. The hours dragged by. On some pretext or other he busied himself in the dome where the assistant, on the movable platform, was sitting in readiness at the eye-piece, constantly observing the eastern sky.

"I see nothing yet, sir!"

Evening set in, and still the report of the observer was the same: "I see nothing yet, sir!"

Was it possible that some joker. . . . ? But Nielson said to himself that by daylight an observation was scarcely to be expected; the shot naturally could not be very large, and the presumably very high angular velocity must quickly take it from the observer's field of vision. By night, however, perhaps they could see the rocket with the naked eye, assuming that it radiated a strong light, and could point the telescope accordingly.

Nine o'clock approached.

"We are now in the same relative position to the sun as the starting point of the rocket at the time of the discharge. Now it must be visible, if it is illuminated, provided it was sent at all." Nielsen climbed the ladder to the observation platform, to relieve his assistant. With trembling fingers he turned the eye-piece, to adjust it to his old farsighted eyes. The mighty tube was almost vertical, for by now the rocket had to appear somewhere near the zenith.

Vainly he scanned the heavens. Time passed; morning approached; nothing!

But wait! A cry of joy escaped the aged scientist. There on the firmament was a glowing streak. In a loud voice he called the assistant.

"Is it visible, sir?" asked the latter hastily.

"We have been swindled, after all!" replied Nielson, disillusioned. A meteor had tricked his fevered imagination. He left the observatory, utterly exhausted.

CHAPTER III

Korf Hears the News

COUNCILLOR HEYSE, the director of the national airport at Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance, was sitting in his private office and turning the leaves of a heap of newspapers. One item in particular seemed to hold his attention. Hastily he threw away his cigar and pressed the button of an electric bell.

"Please send me Chief Engineer Korf at once!" he said to the clerk who answered the bell.

In a few moments appeared the man sent for, a broad-shouldered blond fellow, the technical brain of the Victoria airport.

"My dear Korf," the director greeted him heartily, "I must unfortunately give you some bad news. Please sit down.

"You know," he went on, "that we cannot carry out your project until we have the necessary money at our disposal. My visit to the government to establish a suitable credit has unluckily met with no success. Reconstruction, cutting down expenses, government economy, the burdens of the peace treaty—those were the ever recurring arguments on which the refusal was based. We may absolutely give up hope."

"Then I must simply turn to the public, councillor!" said Korf calmly. "The masses will have more understanding than the narrow-minded parliament."

"Do not hope for too much!" interjected the director thoughtfully.

"Let the director recall the Echterdingen catastrophe, when Count Zeppelin's dirigible came down in flames and was destroyed. In spontaneous recognition of the greatness of Zeppelin's work the German people opened heart and purse, and in a few weeks millions were at Zeppelin's disposal. And to-day it is a question, not of controlling the air but of conquering space, the universe."

"You are an optimist, my dear Korf!" replied Heyse. "The public is as yet too little acquainted with you and your work. Your invention is not trusted, and—believe me—the Germans give no money without assurance of success, especially in this general shortage of money.

"Exhibit your space ship to the public, travel in it to the moon, with a safe return; then, indeed, you may have any sum to build further models."

"This is just the tragedy of many great inventions! First success, then money! And if success is impossible without money, the finest thing sinks into oblivion."

"You are looking at the dark side of things, councillor!"

"What do you estimate as the lowest possible cost of the first ship ?"

"From eight to nine hundred thousand marks will suffice. A still smaller and cheaper model is unfortunately impractical. One would think that this sum could be collected. Just ten pfennig from every wage-eamer of Germany would be enough. If the nation realizes what the question is, it will gladly sacrifice a few pfennig."

"Yes, if the nation realizes. But it realizes only what it sees. And then, one more thing: you are too late. The Russian is already at the goal."

"What Russian?" asked Korf absently.

"You surely remember the Suchinow publications of two years ago, in which exactly your idea of the space rocket was worked out. . . . ."

"Oh, yes! I know. He only lacked the principal feature, the dynamic cartridge!" said Korf with a laugh.

Director Heyse excitedly turned the pages of the newspaper.

"It is not so harmless as that! The man seems to have invented the dynamic cartridge or an equivalent substitute. Here, read this!"

Quickly Korf seized the paper. On the first page, in heavy type, running the entire width of the page, he read:

"The shot into infinity has become reality. The following startling radiogram has just arrived:

"'Bucharest, September 7, ll P.M. To-day at 9.25 P.M. start of Suchinow space rocket from Calimanesti to moon. Further news follows.'

"We give this report with reservation. A confirmation of the news is awaited. As we fully reported in No. 47 of last year, Dimitri Suchinow of Little Russia about two years ago conducted the first experiments. . . . ."

Korf read no further. His eyes flashed.

"Can the Russian," he murmured, "also have discovered the dynamic cartridge? Strange!"

Shaking his head, he studied the article to the end.

"Well?" asked the councillor.

For a time Korf did not reply; then he said slowly: "I do not know what propelling force Suchinow is using for his rocket. One thing is absolutely sure: if it does not attain the necessary exhaust speed of at least 3000 meters a second, the Russian will not reach the goal. And I think I can correctly state that this performance can be surely attained only by my new machine with liquid fuel, If Suchinow, as is very probable, is operating with solid explosives of the type of the dynamic cartridge, he will not liit his machine above the field of attraction of the earth, or else . . ."

"Or else?"

Stressing each word, Korf completed his statement: "Or else he will pass the limit of the earth's attraction by using up the last supply of energy, but then he will never return."

"A frightful thought!" groaned Heyse. "Unfortunately a warning would already be too late." Korf took up the newspaper again. "The rocket ascended last night."

"Even if it were not too late, it would not help. D0 you really believe that an inventor would seriously consider the warning of his rival? Fancy his letting himself be induced to abandon his enterprise with the goal in sight! Such a warning would also be thought by the public the manoeuver of a rival and would expose you to ridicule without helping anyone. No, it cannot be done at all."

"There still remains the hope that Suchinow has simply released an experimental rocket without occupants. The report certainly does not mention any passengers. But what benefit will astro-physics derive, if a lifeless machine is sent up without an observer, or if the observer does not return alive? Either way, the shot into infinity is an interesting experiment but nothing more, and it will end in a fiasco."

"So much the worse, if the Russian fails!" cried Dr. Heyse. "Then public opinion will be aroused and we shall have no success at all in collecting money for an apparently discredited affair, the hopelessness of which will appear established by this mishap."

"My plan is not hopeless and cannot be discredited by Suchinow's presumable mishap," replied the inventor firmly. "I sincerely beg you, Councillor, to start a public drive for funds. I trust the judgment of the German nation. And now may I be excused? A visitor is waiting for me in the laboratory."

"Incorrigible optimist!" grumbled the councillor, when Korf had gone. "He does not even wonder whether this drive for funds will be sanctioned!"

To Mother Barbara's

APPARENTLY unconcemed, Korf hastened to his laboratory, where Uncle Finkle was already awaiting him impatiently. In one hand the newspaper, in the other his inevitable pipe, Sam ran to meet his brother-in-law, gesticulating and shouting from halfway across the room, so that his voice broke:

"Have you read it? There is a race for the moon! The Russian. . . ."

"Apparently has money!" interrupted Korf. "That is his only advantage. Yet he will get to the moon with money just as little as I shall without it."

"Well, the question of money is not so difficult. Just sell some licenses." With a roguish wink he nudged his friend.

"Licenses?"

"Of course! The simplest thing in the world! Mampe will pay you a pretty penny for the sole right to install saloons on the moon. Don't you think so ?"

"It is too bad that apparently there is neither tobacco nor wood on the moon, or I should gladly give you the tobacco pipe monopoly!"

"Thank you very much! Unfortunately I have no use for it. I intend to end my days here on earth. But, joking aside," added Sam sorrowfully, "it is cursedly unpleasant about this rocket. Where did the fellow get it?"

"It is nothing remarkable," answered Korf calmly, "that the very same discovery should be made at the same time by different persons who have no connection. The usual duplicity of events! Besides, this Suchinow came before the public with the project of spatial navigation somewhat ahead of me."

Angrily Sam knocked the ash from his pipe.

"The devil take the entire rocket business, for all I care!" he grumbled. "But if people absolutely have to travel to the moon, then I think it need not be granted to a Russian to be the one who wins the laurels."

"He is not there yet, Uncle!"

"I hope he breaks his neck! I must dissolve my anger, or I shall burst. Come, lad, let us go to Mother Barbara's for a pint. . . ."

"Don't you want to see my experimental model?"

"That would be bad, Gus, very bad! With this wrath inside me? Impossible! The only help is a good drink. Trust old Sam; he knows the things of this earth. When I was just a lad, I often found consolation for my bad lessons by going to Mother Barbara's."

Firmly he took his resisting brother-in-law by the arm and led him away.

In the narrow drinking room of Mother Barbara's inn guests were already sitting, in spite of the early afternoon hour. They were disputing loudly and eagerly about the great event oi the trip to the moon.

"The attempt ought to fail," burst out a stout grain merchant, striking the table with his fat hand, so that the glasses clinked. "It's a real shame that a fool of a Russian is getting to the moon ahead of us people of Friedrichshafen. Who built the first Zeppelin? Who flew over to America? We did! And who started this whole business of travelling to the moon? We people of Friedrichshafen. And now are we just going to look on? That is not right, no, it isn't!" Hurriedly he emptied his glass.

"It is terrible, terrible as the devil!" affirmed his neighbor thoughtfully.

"Do you remember," went on the merchant, "what a stir it made when the ZR 3 flew across the ocean, when the whole world looked at us here in Friedrichshafen? And now the moon and the stars would be looking at us, too, if Korf had hurried a little more. Isn't that so?"

"Perhaps Korf sold his invention to the Russian," pwhispered his neighbor behind his hand, moving a little closer. "We don't know!"

"Don't talk nonsense! Korf giving his business to a foreigner! You don't know him! No, Korf wouldn't do things like that, and now he has invented something quite new, very much better."

"Then why doesn't he build such a ship, eh? Why does he let the Russian fly off and just look on?"

"Well, he put in all his time and ran out of money."

"But look here, this Russian has done it. I don't know, but the whole thing doesn't look good to me."

"Look here," interrupted a third. "This whole Suchinow business is just a swindle! Have you seen the rocket, or has anybody else seen it?"

"Not that I know of!"

"But we could see it flying to the moon. We see the moon all right!"

Busily Mother Barbara ambled around among the tables. She hardly had a chance to stop in her filling the glasses. It suited her nicely. She rejoiced at every event which could excite the people of Friedrichshafen, because excitement causes thirst, and thirst must be quenched. She enjoyed nothing so much as seeing empty pint steins before her guests.

Suddenly the conversation at the head table ceased; two new guests had come in. Inquisitively the people looked at the couple, well known to all Friedrichshafen, persons especially noticeable on this day of days.

"Good day to all of you!" said Uncle Sam jovially. Korf merely nodded absently and took a seat at a table in the partitioned comer behind the buffet.

"Yes, old Sam is still alive, too!" was the greeting of the fat old landlady to the friend of her youth, and she fairly beamed with joy at seeing him again. Without waiting for the order she set two glasses of old Rhine wine on the table and then began a very lively and extensive conversation with Sam. The inquisitive guests at the head table, who were hoping to learn all sorts of things about the moon episode, soon turned away disappointed and bored, beginning again their interrupted dispute, first softly, then louder and louder, with an incessant ?ow like a mountain torrent. Only an unintelligible confusion of voices, occasionally interrupted by heavy pounding on the table, came through the thick clouds of tobacco smoke.

Korf sat silently in the comer. The newspaper announcement occupied his mind still more than he showed. What kind of energy accumulator did Suchinow possess, that he should venture to despatch the rocket? Would this event harm or help his own plan? Would the rocket really reach the moon? Above all, was there an observer in the machine, and was he still alive? The evening paper would surely bring more news. Besides that, Korf did not think it impossible that the rocket would be visible this evening. As to seeing it with the naked eye, that he certainly considered doubtful.

"A splendid woman, this Mother Barbara!" said Uncle Sam, when the landlady had again turned to the head table, rousing Korf from his revery by the words. "She outlives generations, and her wine is splendid. Here's to your health, lad!"

The Disaster

SAM raised the glass to the level of his eyes, swung it a few times in a circle, sniffed the fragrant liquid, took at little sip, and smacked his lips. His lower jaw trembled like the throat of a tree-frog waiting for a fly. He sniffed again and took another drink. Thus it was a long time before the old connoisseur set down the glass again, wiping his mouth and uttering a deep sigh of content from his very soul.

"Now I am more in the mood, Gus; just fire away, what do you think of this new thing? It's probably a swindle, isn't it ?"

Korf shrugged his shoulders.

"Who could be interested in exciting the world with such false news? It is rather late in the year for an April fool joke of this kind!"

"Just tell me directly, Gus, why your work is progressing so slowly that someone else could get ahead of you?"

"There are various reasons, Uncle Sam. Two years ago I had already made considerable progress in preparing the rocket. I had put in all my available capital. And then came the catastrophe!"

"That is right. You wrote me once about a great fire. I was then in Bombay, having quite a time with the English. They absolutely wouldn't believe that I had as little to do with the Indian disorders as Mother Barbara with the moon rocket. How about this catastrophe, anyway?"

"Somehow the small supply of my dynamic cartridges seems to have taken fire spontaneously. Maybe there was a short circuit. At any rate, they exploded in my laboratory, luckily when nobody was there: Not much remained of my work, you may well imagine. My assistant, a Hungarian student, came near losing her life in the flames. The reckless girl wanted to rescue the box of construction plans from the fire. It was crazy, with the incessant explosions. I tell you, Uncle, my heart stopped beating when I saw Natalka plunge into the flames. I thought she was lost; I raged at the firemen who refused to follow me into the fire to save Natalka."

Korf remained silent for a while.

"Did you save her?" asked Uncle Sam, much interested.

"I did not find her. How I ever got out of that flaming inferno again is a mystery to me to-day. Later I was told that I was found unconscious close to the fire. For days I lay between life and death. All my life I shall bear the scars of my burns."

"And Natalka?"

"Fortunately she recognized in time the hopelessness of her mad attempt and plunged into the lake with her clothing all on fire. That saved her. She escaped with the loss of her splendid long hair. I shall never forget this courageous helper, although. . . ."

Korf did not finish the sentence.

"Although? Why, what did she do to you, Gus?"

"Oh, nothing! She remained here a few weeks more and helped me very much in reconstructing the dynamic cartridge. The fire had destroyed all my supply."

"And then ?" asked Sam stubbornly.

"And then? Then she asked for her release. I could not keep her."

"S0 that was the way," said Sam, and he slowly repeated the words, "She asked for her release." He seemed to be thinking of something other than what he said.

"Speak up, lad!" he remarked after a few minutes, while he refilled his pipe. "Isn't it striking that this Natalka went away so suddenly and without cause, only a comparatively short time after the fire?"

"Without cause?" Korf laughed bitterly. "Without cause? Natalka is now living in Berlin as the wife of the apothecary Mertens; maybe right now she is a charming mother!"

"Oh, that's how it is!" said Finkle, whistling through his teeth; he was reflecting. Poor Gus, he thought. Then he said aloud:

"I thought you were going to tell me more about your invention than about the fate of your assistant."

"That can be told in a few words. I had to start again almost at the beginning, and quite by chance I hit on the combination of gases for fuel on which my new model depends. If the airport had not occasionally given rue a little help from the surplus funds, I might calmly have buried all my hopes after the fire. Now I have made so much progress that I can build the first practically serviceable space ship as soon as I can get the necessary capital. That is terribly hard in Germany at present."

"And foreign capital?"

"That has been offered me several times."

"Well?"

"Uncle Sam, I would rather destroy my whole invention than let this, too, go to some foreign country. Isn't it enough, in case of a new world war, that the Americans threaten us with our own Zeppelins, that the Japanese rule the seas with our Krupp cannon, and that the French are making steel with our Saar coal? Truly, other countries are equipped with our own best weapons, so that they can attack us at will, if an occasion arises. No, Uncle, my space ship must and will remain a German national affair."

"The trick of this Suchinow is all the worse!"

A Strange Coincidence

SAM again carefully sipped his wine, looking intently at his brother-in-law over the edge of the glass. He remarked quite without any previous connection:

"Do you still correspond with Natallra, that is to say, Mrs. Mertens?"

"She writes to me off and on, telling about her household affairs. The former student seems to have become a model housewife!" replied Korf drily, drawing spiral figures in the ash tray with a match. "Of course I send her a few lines off and on, too; but she never speaks of my cares and plans. Naturally! She has quite different interests now!"

It did not escape Uncle Sam, with what warmth Korf spoke of Natalka and how indifferently of Mrs. Mertens.

Gus, Gus, he thought, you seem to have scorched something besides your skin in that firel But another idea passed involuntarily through his mind.

"Gus," he began, "do Natalka's letters actually come from Berlin?"

Korf looked up in surprise. "What a strange question!"

"I only thought it somewhat unusual that a Hungarian student should marry a German druggist."

"Well, chemical knowledge may be useful to a druggist's wife," said Korf bitterly, pulling a battered envelope from his pocket. "There, see for yourself! You may perfectly well read the letter, which I got only a few days ago. It is no love letter, such as is kept from profane eyes."

Sam took the letter. "Too bad it isn't, Gus; isn't that so?"

Korf paid no attention to this remark. "Besides, I have met Mertens myself. The young couple visited me once after the wedding."

"He didn't impress you much, this Mertens?"

"Good Lord, he isn't a hunchback!"

Sam carefully read the letter. In firm and almost masculine characters it stated that the writer was very well, that Mr. Mertens was a model husband, that the "Angel" drugstore did a fine business, that this settled existence showed that though their work together in Friedrichshafen was a pleasant memory, woman's place was not in scientific work but in the home, and so forth.

"The only thing missing is some recipes!" mocked Sam.

"Uncle Sam!" cried Korf, reproachful and injured.

"Lad!" said Finkle, rising gravely. "I know and understand; this Natalka has made a fool of you. Everybody has his youthful fancies, and no one can say anything against them. But Gus, a woman who writes such silly meaningless letters—why, Gus, such a woman is not worth one hour's thoughts from a man like August Korf. I must say so, Gus! And if to rescue the honor of your adored one you think you have to take a pistol shot at old Sam, well, please go ahead!"

With a mighty swing of his arm he threw the letters on the table, striking the paper with the fist which firmly held his pipe, so that a rain of ashes and burning tobacco poured over the table. He must have been greatly excited to subject one of his beloved pipes to such an unaffectionate treatment.

Korf shuddered; then he said in an aggrieved tone: "I cannot contradict you, Uncle. If I did not know Natalka's handwriting so well, I could not possibly believe, good heavens, that Mrs. Mertens and my—my assistant were one and the same person!"

Dissatisfied, Sam cleaned up the table, testing the mishandled pipe and knocking the ashes from the letter. The postage stamp had fallen from the envelope, and he tried to stick it on again-mechanically, as though trying to remove all signs of his outburst of anger.

Suddenly he stopped, held the envelope under the light, examined it with first one eye and then the other, and shook his head thoughtfully. On the place where the stamp had been stuck was written in pencil "30/8".

"Strange," murmured Sam, "to write the date of the letter under the stamp!" Then he took up the letter again. It was dated August 30, which agreed with the pencilled date. The Berlin postmark had the same date.

Then his wrinkled face lighted up; a sudden idea seemed to brighten him, and contentedly he again surveyed his wine glass.

Well—the letter was written by Natalka and posted by Mrs. Mertens in Berlin on August thirtieth. But. . . .

He put the envelope into his pocket, on the reverse of which was the sender's address, returned the letter, and said, ignoring what had just occurred:

"Then money is what you lack! I shall just see about that a little. Old Sam knows many people. Who knows, perhaps I can be helpful to you in this respect. Tomorrow I must be off to the Turkish Consulate in Berlin, and I shall keep the matter in mind.—Mother Barbara, bring me another of the same!"

A Sleepless Night

IN the streets and alleys of the usually very quiet little city on Lake Constance it was lively the next night. When darkness set in, the people poured out to the lake in crowds. The entire city, to the last man, seemed to come out. They crowded about the boats which were for hire, the owners of which were doing splendid business. Recognizing the demand, they made a special increase beyond the ordinary rental fee. As far as one could see in the darkness, there were canoes, rowboats, and any kind of thing that would float on the water. With telescopes and opera glasses the people unceasingly scanned the sky with an attention such as had hardly likely ever been given the old moon in this district before.

The evening papers had confirmed the sending of the rocket, and no dweller in Friedrichshafen was willing to let this event escape him, though opinions regarding visibility and invisiblity were very divided. On this evening many saw perhaps for the first time that most of the stars, like the sun, rise in the east, climbing higher and higher in the firmament, to sink again to the western horizon. Many noticed or learned, to their astonishment, that the pole star, on the contrary, seems to stand still, while the entire starry heaven revolves around it.

But when the hours passed and nothing at all sensational occurred, no arc of fire in the sky, no glowing, speeding shot, no explosion on the moon, then gradually the older persons began to go home disappointed, others followed, and all at once commenced the general migration back to the city, though morning was still far o?. Only the more stubborn ones held out until the grey of morning, until the rising sun colored the eastern sky and extinguished all the splendor of the stars.

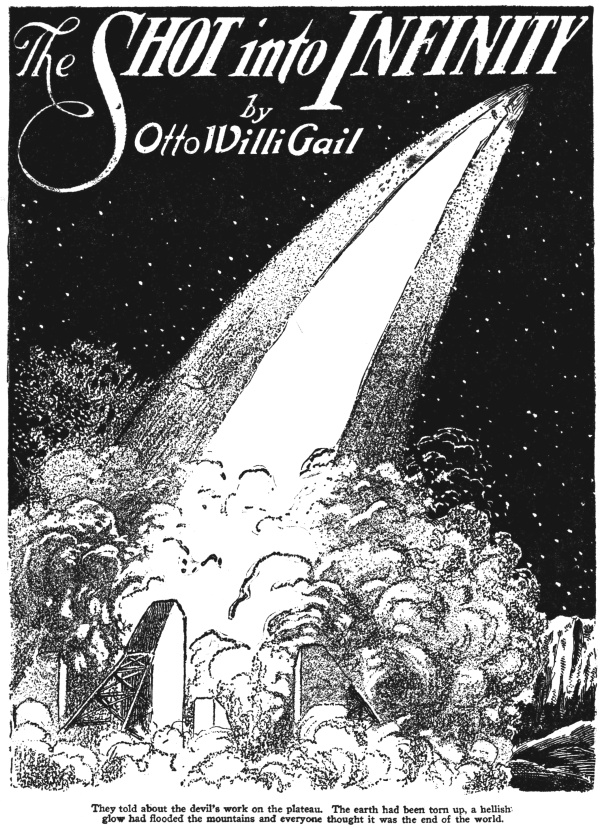

On the next morning the papers brought reports columns in length. All the reports, including those from other countries, showed a certain disappointment that nothing could be observed; yet there was scarcely any doubt that the shot had actually taken place. A leading Berlin paper printed the description by its Roumanian correspondent. To be sure, no one had actually seen the shot, but in the night in question, soon after nine o'clock, the dwellers in the vicinity of Calimanesti had waked in fright at a loud thundering crackling sound like machine gun ?ring. In great excitement the Roumanian mountaineers, who could not understand the frightful noise, had ?ed down the valley. The cattle had become unmanageable, horses and oxen had broken loose, increasing the general confusion, added to which was the incessant howling of the dogs, while the mountain beasts, heedless of men and dogs, had fled through the villages in wild terror.

The thundering had also been heard in the great hotels of Ramnicul Valcea, and some of the guests claimed that they had seen a dazzling light over the mountains to the northeast.

Most of the observatories which had been asked for information about their observations and opinions assumed a very cautious and reticent position.

The Babelsberg Observatory, Berlin, wrote as follows:

"Until we are informed regarding the dimensions, velocity, and direction of flight, we can form no opinion regarding the possible visibility of the rocket. It is, however, certainly striking that up to now the rocket has not been perceived by-any observatory in the world."

The Greenwich Observatory, reporting to the Daily News, offered rather more hope:

". . . . Still it is possible that the rocket is illuminated insufficiently or not at all, for which reason it can only be seen when it emerges from the shadow of the earth. We can make no prediction when that will occur, since we have no basis for calculation."

Even the following night brought no certainty, since a thick covering of clouds had formed over the entire Western Europe, and the commencing autumn mist alone was enough to make observations extremely difficult.

_ Soon such strong doubts had public expression that no one dared to look up at the sky any' more, for fear of being mocked as a "rocket-gazer".

This development of the matter was not at all pleasant for Korf. Even if he himself, on a logical basis, believed that the shot had succeeded, it was fatal for the public to think itself made fun of. What effect would this -have on his collection of funds, now just ready to start? The public might after all pass over a failure, but it would never pardon having been fooled. Doubtless the inevitable inclination to generalization would produce at least a very reserved frame of mind as regards the question of spatial navigation.

A bad omen for the fate of the national collection!

Korf grew very angry.

"This botcher!" he growled. "Apparently the machine was badly made and has come to grief. It would have been better if he had kept quiet about his shot into infinity. Public opinion is quickly destroyed!"

It did not occur to Korf that he was really heartily wishing success to his dangerous rival. He honestly hoped that the rocket would still be discovered in its path to the moon.

CHAPTER IV

The Riddle

FROM the Uhlandstrasse station of the Berlin subway a man slowly climbed the stairs to the open air. He looked about in hesitation and then walked over to a policeman.

"The Angel drugstore?" answered the latter to his question. That has been closed for six months, and the "building is being made over to a moving picture theatre."

The inquirer gave polite thanks for the information. Pleased, as though the policeman had given him very satisfactory news, he continued up Uhlandstrasse, carefully examining the white tablets with the name of the streets, and turned into a side street. Stopping before a high, dreary lodging house, he drew from between the tobacco pipes and pouches in his pocket a crumpled envelope, comparing the address with the number of the house.

"Well, just wait, my dear Mrs. Mertens!" he said to himself with a grin. "You will be in our hands, after all!"

Then he entered the house and stamped up the grey creaking stairs. Etch story contained three dwellings, and accordingly old Sam had to study several dozen nameplates of occupants and visiting cards of sub-letters, until finally on the fourth floor at the right he saw the name Mertens shining on a polished brass plate.

For a long time nobody answered his ringing. He pressed the button a second and a third time, when he at last heard shuffling steps in the corridor. The door, secured by a safety chain, opened barely a hand's breadth.

"Who is there?" cried a thin squeaky voice, apparently belonging to a woman and startling Sam by its tone. He never could endure talking with invisible persons.

"Just open the door, my good Mrs. Mertens, I am not a burglar," he said in the friendliest tone possible to him in his sudden excitement.

An ill-smelling vapor of sour milk and steamed sauerkraut came from the narrow opening.

"What do you want?" asked the voice behind the door.

"I shall explain it exactly, as soon as you have opened the door, Mrs. Mertens!"

"But I am not Mrs. Mertens. They moved out long ago."

"Is that so?" said Sam in surprise. "Then why is there a plate on the door with the name of Mertens?"

"Are you from the housing commissioner?" said the voice, in which there now sounded a blending of mistrust and worry.

"Do not be alarmed, my good woman! Please tell me where the Mertens live now, and I shall not bother you any more."

"Ask the porter!"

Samuel Finkle was glad to follow this rude but practical direction, and luckily found in the porter a creature of flesh and blood—very much flesh, indeed.

"Well, the Mertens!" said he. "Yes, the Mertens! Just keep your fingers away, my dear sir. Mr. Mertens is not going to keep his eyes shut much longer. I advise you to stay away!"

Uncle Sam could make no sense of the stuff the man was saying, yet he congratulated himself on having found so talkative a person. Here he could count on learning more than from the nivisible spirit on the fourth floor.

"I know you mean well by me, porter," said he, "but will you please be so kind as to express yourself more plainly. I do not understand you."

Then the porter laughed so loudly that it reechoed.

"Oh, don't try to fool me that way! Of course a person does not hang his dirty linen in the market place. But you don't need to hide things from me; I can keep quiet. I've seen plenty of fellows sneaking up the stairs, when Mertens was over at the drugstore."

The porter grinned in a greasy, ambiguous way, perfectly comprehensible to Sam.

"Fortunately they moved out before we had to get after them with the authorities. This is a respectable house. Of course we put up with things and sometimes shut both eyes a bit. But she went too far, till it even caught the attention of the tax collector on the first floor, and anyway her shamelessness was getting too much for me."

"Tell me, how did this Mrs. Mertens really look?" asked Finkle thoughtfully. The porter eyed him from top to toe. There was a threatening tone in his words:

"See here, are you making a fool of me?"

"Not at all; I really do not know Mrs. Mertens. I just wanted—well, I am supposed to give her greetings from an old friend."

"So that's it—from a friend! I really might have thought that you were not the lucky man. She used to favor younger cavaliers."

Uncle Sam was getting ashamed of the unworthy role which, against his will he had forced on his young friend. Still, wasn't it somewhat justified? Hadn't there doubtless been tender relations between Korf and Natalka?

"How does she look?" went on the talkative porter. "Good Heavens, she's a pretty thing, one must admit; and," he added pleasantly, "she has legs, such legs that it is no wonder the men run after her. Oh, how does she look? She has short black hair, a white skin, and—Heavens, how shall I express it!—she looks like a vaudeville actress or something of the kind. The devil take the women!"

Uncle Sam was getting noticeably uncertain in mind.

"Short black hair, you say? About how old is she?"

"Much too young for you, you may depend on that!"

"And do you know her first name?" Sam went on politely, though he felt a desire to give the impertinent man a good box on the ear.

"You have me there! She has a lot of names, a different one for everybody."

"And where did you say the Mertens were living now?"

"Shortly after they had sold the drugstore, it was the turn of the dwelling. There is a lot of business in that nowadays. It is hard to pay for lodgings, especially in a pretty, roomy building, if a person to whom you let a room moves away. After that they went to Vienna and now, so far as I know, they are in Budapest. I recall, that is right. Mertens recently wrote me about the coal which was still in his cellar, and he mentioned that his wife was again appearing at the—the—what do you call it?—the Or. . ."

"The Orpheum, don't you mean?" put in Uncle Sam, who had a good knowledge of the world. "And the address? Have you the letter still?"

The porter opened a drawer of his desk and searched in a regular mountain of papers, while Sam strove to bring his ideas to order. Had his Gus been really attracted to such a woman—his Gus, whom he loved as a lather would his son. To be sure, it often happens that intellectually gifted, eminent men seem smitten with blindness when women are in question. Yet he would certainly have credited his brother-in-law with a better understanding of mankind.

"Here is the letter!" The porter roused him from his meditation and slowly spelled out the words:

"Budapest, Szabolcs Utca number 54-oh, read it yourself! I don't know Hungarian."

Sam readily believed that and wrote the address in his notebook.

"One more thing: have you any idea what Mrs. Mertens' maiden name was?"

"Yes, I know very well, for many of her cavaliers knew her only by her maiden name and used to ask whether a Miss Weiss did not live here."

Old Sam's knees shook. Weisz, the Hungarian name Weisz, which the porter took for the German name Weiss, was the name August Korf had given him, the name of Natalka.

Thanking the porter, he gave him half a mark, because he was always accustomed to be sparing in the way of tips, and set out for his hotel.

Finkle Scores

HIS entire artfully formed hypothesis was trembling in its foundation. He had set himself up as a detective, luckily only to himself. He was getting confused. What had he expected? What was more natural than that Mrs. Mertens used to have the maiden name Weisz? Why did this person who was formerly assistant to his brother-in-law and afterward married to the druggist Mertens of Berlin concern him? Why did he think himself pledged to shield this woman?

Truly, this Mrs. Martens was not worthy of occupying the thoughts of Samuel Finkle. But—was he really shielding Mrs. Mertens? It was in fact only Natalka, whom Gus still cared for. His Gus, whom he wished to free from the uuexpressed reproach of having been attracted by an unworthy and unintelligent woman.

Yet Natalka and this Mrs. Mertens were one and the same person!

In an ill humor he pushed into the crowded subway car, worked his way among sharp hatpins and glowing cigarettes, and finally came to a stop in the crowd, firmly wedged between two tall gesticulating natives of Berlin, who were chattering away over his head. This disturbed Sam in his already hopelessly confused reflections. Mechanically he reached in his pocket, to protect his pipes from being crushed, and in so doing felt Natalka's letter between his fingers.

Certainly there was something wrong about this letter. But what?

Anxiously he held fast to this idea and tried to free it from the chaos into which all his logic was threatening to sink. "Letter—letter," he murmured to himself, in order not to forget again that connected with this letter there was something wrong, about which he had to reflect.

At Nollendorf Square he had had enough of the crowd, and he worked his way out of the car. With amazed smiles those in the station watched the slender little man who kept saying to himself "Letter, letter" very audibly while rushing away as though something hounded him on.

In exhaustion Sam threw himself on a bench. He began to review his thoughts, and again a light came to him.

"If Mrs. Mertens is identical with Natalka," he said aloud to himself, in the manner of an examiner to a candidate, "why doesn't she write to Korf from Budapest? Why does she choose this unusual detour by way of Berlin? Why does she tell about a drugstore which long since has ceased to exist? Why write these letters ahead of time at all? And who posts them in Berlin on exactly the days which are noted on the sealed envelopes? Can she have someone in her confidence here, to look after these letters?"

Again he looked at the postmark. It was that of the postoffice in Uhlandstrasse.

Perhaps it was this porter, who knew so much and whose sense of honor and propriety had required some impetus from the tax collector on the first floor to reach an ordinary and natural indignation! How could he have forgotten to make inquiries about this?

No sooner thought than done. He quickly set out on the return trip. This time he did not take the subway, the unpleasant mode of travel which confused all his ideas, going on foot instead.

In astonishment the porter beheld his visitor reappear. His reception was not excessively friendly; the stingy half-mark piece had perceptibly lowered his opinion of Mr. Finkle.

"Good Lord! What do you want this time?"

"I quite forgot to tell you my name, porter," said old Sam, determined to go the limit, "my name is August Korf."

"From Friedrichshafen?" blurted out the other in surprise.

"Quite right, porter, from Friedrichshafen. As you know, of course!" This was the man who posted Mrs. Mertens' letters. Calmly and confidently Sam continued: "You still have a few more letters from Mrs. Mertens to me. You may save the postage. I'll just take them with me."

"But I am supposed to post the letters only on certain days! Besides, how do I know whether you are really Mr. Korf?"

"How else should I know about the letters, my good man? Besides, if you will not give me the letters, the matter is not so important but that you may put them in the stove, for all I care!" With that Uncle Sam turned to go.

"Are you perhaps tired of the Mertens woman?" cried the porter maliciously. "If you tell me your exact address and what you say agrees with the address of the letters, then for Heaven's sake take the letters away! I shall be glad to get rid of them!"

Slowly Finkle turned around, named the address of his Friedrichshafen friend in a careless fashion, and then received a little package, which he stowed away in his breast pocket.

His good humor was restored as he left the Uhlandstrasse lodging house, never to see it again.

The Dot In The Heavens

IN the afternoon, on Potsdam Square, there was an apparently hopeless confusion of carriages, automobiles, buses, and street cars. Noise, noise, and still more noise! From the Potsdam station sounded the whistles of entering locomotives, but they could not compete with the shrill yells of the newsboys:

"Berlinger Zeitung, afternoon edition—Tageblatt—Börsencourier—Berliner Zeitung.

Uncle Sam held his hands to his ears as he crossed the busy square and turned into Leipziger Strasse.

"This accursed screaming!" he grumbled. "As if there wasn't enough noise without it, on that windy comer!"

For a moment the calls of the newsboys were hushed. Apparently they were receiving new supplies of papers. But then they resoundcd again, louder than before.

"Extra, telegraphic despatch, Berliner Zeitung! Moon mystery solved! Discovery of rocket!"

Uncle Sam began to listen. The rocket discovered? In his zealous performance as an amateur detective he had entirely lost sight of the final object of his investigations, the rocket. Hastily he purchased one of these papers, still damp from the press, and scanned it quickly.

"The Moon Rocket Found!"

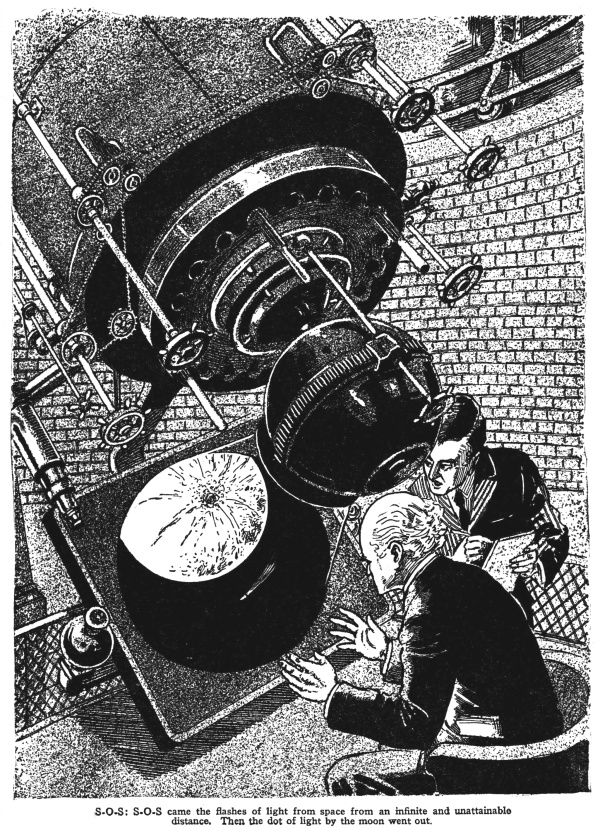

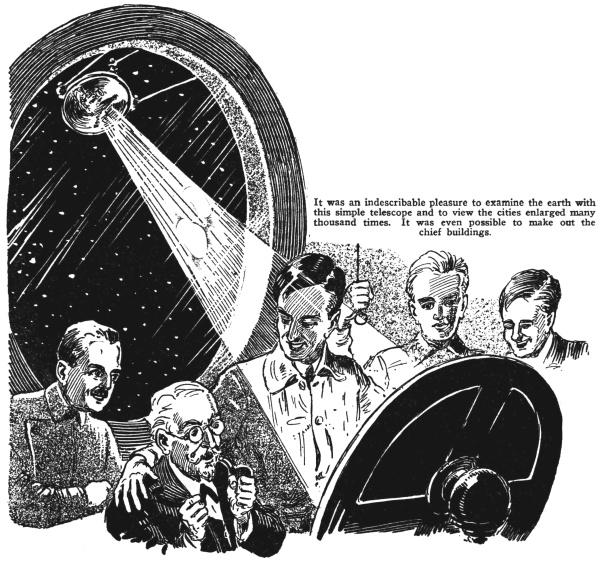

"ACCORDING to an announcement of the Lick Observatory in California, at about 5 A. M. on September 9 (at noon of that day, by our time) a dot of light, with a bluish glow, was observed in the eastern sky, moving with great speed toward the moon. At the moment of observation it was about 200,000 kilometers from the earth.

"This is doubtless the Suchinow rocket, evidently exhibiting a phase of illumination as the moon does, at present appearing in the first quarter. This demonstrates that the rocket has no illumination of its own and has only become visible through the reflection of the sun's rays. Thus is also explained the previous failure in locating the rocket, which apparently emerged from the shadow of the earth only after thirty-five hours from the time of starting.

"Since the Lick observation is dated about forty hours after the start, and since in this time the rocket had covered half of the entire distance to the moon, the arrival at the moon might be calculated for tomorrow morning at about five o'clock (Central European Time). It is to be hoped that the sky will be sufficiently clear for the observation of this sensational event from our Babelsberg Observatory likewise.

"In order to spare our readers a disappointment we warn them beforehand that there is of course no possibility of witnessing this event with the naked eye. Even in the gigantic telescope of the Lick Observatory, with an enlargement of more than a thousand times, the rocket appeared only as a tiny, hardly perceptible dot of light. Accordingly it will be rather pointless to look at the sky during the night with field glasses and opera glasses."

Uncle Sam slowly and carefully folded up the sheet and put it in his pocket. Then he went to a café to refresh himself, mind and body, for further activity.

It was remarkable—eighty hours from the earth to the moon! This was exactly the time required by the Zeppelin sent across the Atlantic in its voyage from Friedrichshafen to Lakehurst.

Was there perchance some one up there in that fragile object, about to visit the moon by morning? Then his thoughts returned to the porter in Uhlandstrasse. What a shameless fellow! Yet Sam bore him no ill will, since he had furnished valuable information. Now he knew that—well, what did he really know? That Mrs. Mertens was Natalka, and Natalka Mrs. Mertens? Was the matter not actually made very involved merely through this "explanation"?

He took out the package of letters. Eight envelopes, all bearing Korf's address in the familiar strong handwriting, all identical, even to the heavy line under the word "Friederichshafen," which was exactly repeated in width and direction. There could no longer be any doubt: all the letters had been written at the same time with the same ink.

"Fine doings!" said Uncle Sam to himself. "Writing a dozen letters at once! No wonder that nothing brilliant results. Still, it indicates energy and persistence."

Then he studied the dates written in the comers where the stamps would be placed. He was interested to note how long a time Natalka had intended these tender attentions to his Gus.

"Great! This woman actually reasons! Of course she could not break off the correspondence suddenly. That would have attracted attention. Accordingly she lets the intervals become greater and greater, and the correspondence gradually goes to sleep. Well! This Natalka is not so foolish as might be expected from the contents of the letters." He had a great desire to open the envelopes. But he did not venture to intrude into the secrets of his brother-in-law. Korf might not like that.

"After all, I can well imagine what there is to read in them," Sam comforted himself. Then he continued with his plans. For a long time he reflected, formed schemes and rejected them, planned like the keenest criminologist, and by the time he left the café had a decision firmly settled.

First he went to a telegraph office, where he sent two telegrams to Budapest and one to Mr. Suchinow, Transcosmos, Bucharest.

After he had procured a berth on a sleeper to ,Vienna, he went to his hotel, told the amazed clerk that he did not require the room he had engaged, and repacked his suitcase.

Whistling merrily, he went to the Silesian railroad station.

CHAPTER V

A Financier's Worries