Help via Ko-Fi

The Red Germ of Courage

By R. F. STARZL

AS THE people of the Twentieth Century had crowded the docks at the sailing of great ocean liners, so now in the latter years of the Twenty-second did they swarm to the broad paved fields in the center of which, in an endless line, stretched the launching pits of the space rocket liners.

These travelers of the freezing outer spaces stood glistening in the sun, their conical tops reared proudly to heights of a thousand feet or more. Their silvery sides were lined with observation ports, but were otherwise smooth except for the scant dozen hooded openings used for navigation only. Strong, sharply cut atmospheric vanes, with the electronic nozzles at their tips, were spaced at regular intervals at their sides.

They presented a spectacle of majesty, confidence—the highest pinnacle of man's achievement—and some of this impressed itself on the sea of humans which fluttered with handkerchiefs and bright ribbons or banners, contributing to the general animation.

The young man who skirted the edge of the crowds had no eye for the beauty of the scene, however. He was hardly more than a boy, just twenty-two, and he was on his way to the freight pits, still a good half-mile away, where the squatty, businesslike space tramps were discharging or receiving cargoes.

Syl Webb's object was to get a job at which to make a living, since the income left him by his father had been swept away by the new taxes. But he had another and greater object—to prove for himself the manhood which had struggled vainly for expression, in his pampered life as a member of the leisure class.

He arrived at length at the end of the glistening new vitricate-paved way, and the small truck which had been dogging his footsteps came to a determined stop, its chimes sounding insistently. Persons who passed the boundaries could not expect porter service. Syl placed a coin in the slot. The machine said "'kyou!" re-released the elegant trunk to its owner, and turned back.

Syl passed several of the rusty or black-painted ships carrying the trunk on his back, until weariness forced him to put it down and sit on it, A calculating-looking petty officer, chancing to see him, left his toilets and accosted him.

"Lookin' for a job, hey?"

"Yes, sir."

"Y' don't look very strong."

Syl flushed. He was of medium build, well-knit, and the tanned legs under his short breeches were well developed. But in comparison to the other's powerful figure he seemed almost puny.

"I can work, sir."

"Where y' get them duds?"

"Why, they're my regulars."

"Aw-gawan! Them's capitalist duds!" He was filled with the vast scorn of the industrial class for members of the coupon-clipping, aristocratic, capitalist caste.

"I am—well—I was a capitalist."

The other bailed a big fist. He suspected he was being made fun of. But Syl's evident refinement convinced him, and a new light glittered in his beady eyes, and a sneer came to his cruel, hawk-like face. There was. triumph in it, and hate, for he had been born on the wrong side of the ever widening social gulf.

"So they've taxed down one more of the damn' parasites! Good for the commission! Well, m' fine lad, you're hired!"

So saying, he reached out a powerful hand and seized Syl's wrist. With a deft twist he forced Syl's thumb into a little oval aperture of the sealograph strapped to the officer's waist. A tiny camera inside the device clicked, and Syl Webb, former capitalist gentleman, was legally made' an employee of the Neptune & Uranus Trading Co., labor division.

THE new recruit looked puzzled.

"Come on, snap 'round!" his new boss commanded. "Get your duffel in an' report fer duty."

"But I don't think I want to. I want to look around—"

"So!" With a hoarse roar. "Insubordnation! Well, any damned time Mark Gunning can't handle a mutinous ground-slob—"

A cloud of fists descended on Syl. He knew a little of the science of boxing—was, in fact, quite proficient—but that was not the same as the fighting of Mark Gunning, cargo master of the Pleadesia. In a few seconds Webb was lying on the ground, his head a mass of contusions. and coughing dizzily from a foul blow to the throat.

With a stream of practiced curses, Gunning picked up his victim and sent him rolling and tumbling down the gangplank toward a cargo door. He picked up the trunk and tossed it after its owner. It missed the plank and fell fifty feet to the bottom of the pit, where it split open. Instantly half a dozen dust-and-sweat-streaked men pounced on the gay-colored synthetic silk shirts and the swank useless harnesses of dyed leather. Donning them in grotesque parody of pleasure-villa nymphs, they danced around under the spouts until driven to their work again by the curses of a port overseer.

Syl lay inside the ship where he had rolled, at the bottom of a steep metal ladder. His head had been cut by a sharp projection somewhere, and blood was beginning to mat his dark, wavy hair, His eyes were puffed shut, and there were tears in them—not tears of pain, but tears of mortification and anger. Somewhere under the soft padding laid on his being by generations of genteel civilization, stirred a feral, blind lust to go back up there—to bite—to gouge—

"Hurt, lad?"

Though Syl had been a recruit just a few minutes, the cultured accents sounded strange to him. With difficulty he opened his eyes enough to see. A man of about fifty was looking through the square opening in the floor above. He was a small man, and rather thin. His neck was scrawny, with a prominent Adam's apple. Graying hair fringed his bald head, and his rather weak mouth was partly concealed by a scraggly mustache, white, and stained blue with merclite, the intoxicating chewing gum.

"It'll wear off," the man said, with a sympathetic grin. "Want to come up to the galley? I'm cooky here."

With assistance, Syl climbed the ladder, and after passing several doors, reached the galley fifty feet above The room was wedge-like in shape, with one end conforming to the arc of the outside shell. Unlike the rest of the ship that Syl had seen so far, it was scrupulously clean. The cook applied hot compresses to the bruises.

"Name's Splade," he volunteered. "Used to be a capitalist, like you. They taxed me down about ten years ago. You get used to it. I'm a good cook—they admit it, and treat me pretty well. Forgotten, most of them have, that I ever clipped coupons. But it may be a little hard on you, lad."

A small bell tinkled, and in an instant Splade dived to the floor, carrying Syl with him. Before the latter could remonstrate, the floor came up as if trying to crush him. It was as if his weight had been increased many fold. There was a dull roaring, which ceased almost immediately, and the abnormal floor pressure gradually diminished.

It was a new experience to Syl. He had traveled in the superbly engineered passenger ships, whose graduated acceleration caused hardly any discomfort, but this expensive refinement was unknown on the freighters.

Splade grinned and rose. "We're 'way above the atmosphere, hell bent for Titan, sixth satellite of Saturn. Going to stop at the mines."

SYL shivered. Before this definite sundering of the earth ties he had entertained, deep in his subconsciousness, some idea of desertion. Now he was irrevocably bound to the ship for at least four months, possibly longer, depending on the length of the stop at the mines.

Like all space freighters, the Pleadesia consisted of a large number of cargo compartments, arranged compactly around a central well which extended from the bottom to the top, ending in a hatchway to the observation and navigating room in the ship's nose. Automatic mechanism, set to the proper co-ordinates, attended to the routine, so that except for supervision the presence of the officers was not really necessary.

Full details of the power rooms, which were located in the thick, stubby vanes above the electron-ejector nozzles, were shown the officers by selective televisor tabs. The navigator foci from the hooded ports, and the usual amplifying auditory systems to all parts of the ship, were provided them also. In the top of the navigating room, at the very tip of the conical nose, was the emergency outlet.

Below the navigating room were the eight or ten cabins used by the officers and occasional passengers. Below these were the cargo holds, galley, hospital and supply rooms though the Pleadesia did not carry a doctor. At the very bottom were the laborers' quarters. The ship rotated in flight, and by centrifugal force generated a fictitious gravity. This enabled one to walk up and down the sides of the well, ignoring the ladders, when out in gravity-less space.

Syl did not descend to the crew's quarters until he had exchanged his tattered silks for coarse fibroids, fatigue clothes loaned him by the cook. A strong bond had formed between them. As representatives of the small leisure class, they belonged to the doomed. Their kind were ground between the upper and nether millstones—the scientifically trained technicists, and the laboring class.

"If you say you came here to get a job, I believe you," said the older man as Syl prepared to leave, "but tell me, you don't plan to be a 'mug,' do you?"

Syl thought of the brutalized crew and shook his head.

"You probably won't understand me," said the new recruit, "but I want to prove my place in the world as a man. I've done nothing but useless things all my life. I've felt the futility of it—but like a fool, I wasted the time I might have been preparing to be a technicist. I could be wearing the gold braid up above if I hadn't."

"But there's the Records Office!"

Syl laughed scornfully. It was well known to everybody in twenty-second century civilization that the government Records Office was a sort of pensionary where those who had been taxed down could eke out a shabby-genteel existence. He had visited it once—had memories of young-old men sticking useless pins into futile maps. Of women, bred for generations to lives of gentle leisure, compiling statistics that would remain unused.

"Yes, I know the Records Office. It's the government's way of saying what a hopeless breed we coupon-clippers are. I'm going to prove they're wrong if I get killed for it. I'm starting with the toughest and the worst of them. I'll study, and win a technicist's school appointment!"

"Yes?" Splade smiled sadly. "That's what I thought; but I was too old, and they found out I could cook." Yet there was-class pride in his bearing as he watched Syl walk down the well.

THERE were about twenty labor mugs in the Pleadesia's crew. They were under the discipline of Mark Gunning. cargo master. This, by the way, was not a regular officer's rating, which, perhaps, accounted for his bullying tactics. Yet, if his was a hard discipline, the crew was hard. The labor mugs, unskilled, usually physically powerful, treacherous and wild, were the skimmings of half a dozen interplanetary ports.

There was Mnig Tah, the Martian. (His Terrestial grandparents had helped colonize that turbulent red planet.) A short quiet man, with tremendous limbs, deep, hairy chest, a habit of looking sideways at a person addressing him. He had the typical swarthy complexion of the human Martian, He was wanted for murder at Marsumium, and wisely refrained from signing on for any freight trips to his native planet, There were the four from the Rio Bias country. Small, lithe, with quick white smiles as they fingered their daggers behind their backs. Even Gunning feared them a little and had made up his mind that something would happen presently.

Or Wannol, the lone representative of Venus—easy going, indolent, whose tremendous arms could, and did on occasion, break a man's back. His thick skin, flabby even to the top of his hairless head, was burned a metallic bronze. Wannol believed himself to be handsome, and it behooved others not to dispute with him.

But most of the mugs were earthmen. Bred in environments of misery, suspicion and hate, they rioted through life, brawling. Most of them were wanted for some crime or other. But no one looked too closely at the labor mugs. They were essential to this age of metal and of science, to do the hard, dirty work which could not be done more cheaply with machinery.

Gunning set them to work scraping the cargo holds which were to receive the concentrate at the mines. Syl Webb was paired off with a black named Hoyden, a grinning, hulking fellow clad, by preference, only in a G-string.

"You not ve'y big," Hoyden said ingratiatingly when they reached the hold assigned to them, "Take bucket, me take scrob." With the toothed chisel he began to scrape the scale off, and as the stuff loosened and "fell" to the curved wall—flung there by the rotation of the ship—Syl Webb picked it up and put it into his bucket. It was the first useful, manual work he had ever done in his life. Despite his aches, he felt almost contented.

The cordial relations between him and Hoyden did not last very long. The big Negro soon begged for some merclite, and as Syl had none, not using the stuff. Hoyden became very much out of humor. He even started a backhand swing, but Syl stepped aside, and there was something in his eyes, suddenly gone steely-gray between their puffy lids, that made Hoyden pause.

The twenty-four hour day, based on Earth time, was in force in the space lanes. When the faraway whine of the annunciator proclaimed eighteen o'clock—six P.M., old style—the men were marched down to the mess room where food, sent down a tube in canisters, awaited them. Begrimed, Syl had begun to resemble his companions. There were some malicious remarks directed at him, which he thought it best to ignore, but mostly the men wolfed their food and said little. The talk veered to a battle royal the night before with another crew on one of the forbidden intoxicating gas chambers that flourished under cover, and Syl was forgotten.

He was very tired, and sought the sleeping cabin, with its tiers of metal bunks. They were all more or less filthy, but he found one near the ceiling, under an air duct from the chemical plant. He did not hear the men quarreling all night over a gambling game that derived from the old-fashioned "craps", nor did he notice the odor of men's sweaty bodies long unused to water. He slept as he never had before.

The next morning an order came down from above for a man to polish the metal work in the upper well.

"Get on up there, you, Webb!" Gunning ordered. "'At's about all you're good for, y' lazy swab." He leered at the savage faces. "Got a loidy up there. Oh, di-mi! Gotta send up a reefined mug. Oh, yeh! Get on up there, y'bum!"

SYL WEBB found some rags and polish and left. There was no one in the upper well to direct him, so he started to polish the nearest bright surfaces. The ordered neatness here, after the filth below, soothed him, and at the same time filled him with regret as he thought of the assured young technicists of whom he might be one.

They passed him by, one by one, sprightly, secure in their positions, masters of this complex mechanical age, before whose guilds even the few invulnerable tax free capitalists respectfully bowed. The chemist, the powermen, the astronomical mathematician passed on their way to and from their stations as the watches were changed, and "Mug" Webb's polishing strokes slowed as he thought of the times when he, on some passenger flyer, had sat at table as social equal of men such as these.

Following a handrail, he came to a narrow lateral passageway ending in an observation bay, the only one in the Pleadesia. He caught his breath at the beauty of the scene. They were passing Mars on its sunward side. It filled a quarter of the unfathomable black space-vista. By contrast the reflected sunlight was dazzling. For once the incessant red dust storms were absent, and the canals, like delicate lacework, could be seen unobstructed.

"Beautiful!" he exclaimed.

"Oh, I love it!"

Beside him, rapt eyes on the spectacle, stood a girl who put the beauties of the celestial voids to shame. She was about twenty, possibly a little less. Her slender young body was wrapped in the gossamer long robe of the era, that concealed and yet maddeningly accentuated the delicate feminine curves of her figure.

Her uncovered head in its amber nimbus of silky hair was thrown back. She gazed at the spectacle under long lashes that left her eyes, dark blue, deep in shadows. The deep aesthetic emotion had brought bright spots of color to her cheeks that, in their perfection, defied the glaring light streaming into the window.

"Beautiful!" she breathed.

"Very beautiful!" Syl said devoutly, looking at her.

"It always affects me the same way," she said. "There's no more lovely sight in the solar system."

"Nor in heaven!"

She turned, smiling, for she was not unused to gallantry; but when she saw him her expression changed to horror. Her white hand flew to her throat and she stood as if paralyzed for a moment. Then she was gone.

Syl was puzzled. Then the realization of his position came to him. For a moment he had forgotten that he was no longer an aristocrat, but a mug. How his bruised, unkempt appearance must have shocked her!

In a bitterly unhappy mood he finished his task, then sought out Splade in his galley to tell him what had happened.

The little cook surveyed him with horror, a trickle of blue-tinted merclite saliva running unheeded out of the corners of his mouth.

"You fool!" he blurted. "That's Maida Stanley, daughter of the chief technicist at Titan! Of all the fool things you could have done, why did you have to speak to her? Man, don't you realize you're a mug now? If she reports you, you'll spend the rest of your life in the ore docks."

Syl did not think of what would happen if she reported him. He thought of the gentle line of her white throat in the garish light of Mars, of the thrilled, impulsive words she had spoken to him. He thought long of her that night, lying on his metal shelf, one arm over his stubbly face.

THE next three weeks were the most miserable and the most satisfying in Syl's hitherto protected life. He resolutely banished thought of the girl to the back of his mind, where her memory tormented him only occasionally. With conscious purpose he identified himself with the mugs, became one of them in their rough ways— even learned to think like them.

In the backbreaking hours of labor he liked to think of his fight with Naylor Bey, the giant Mazurian, that first week, Naylor Bey had his own style of fighting. He tried to shove his wirelike whiskers into Syl's throat as he held him in a bear's hug. But Syl evaded him time and again, cut him to pieces with scientifically spaced punches, knocked him, bleeding, into a corner. Bey regarded him after that with puzzled wonder, and showed no resentment. Splade, who had received the details of that fight from one of the mugs on an unauthorized visit to the galley, exclaimed enthusiastically as he taped up a cracked rib:

"You're showing 'em, boy! You're showing 'em! The mugs are more'n half for you. Oh, if I was only your age!"

Syl Webb smiled, but said nothing. A little later, swaggering down the well, he met Mark Gunning. who accorded him a grudging, half friendly nod Syl did not go looking for trouble. With all his flowering self-confidence he had also acquired an atavistic cunning. To live long one must not be too pugnacious.

He learned to play the mugs' games, and to chew merclite in moderation, A goodly supply of this dangerous solace had been smuggled aboard by a member of the crew, and was for sale. He acquired only a slight liking for the acrid, heady gum.

For the time being, of necessity he put aside thoughts of becoming a technicist. He had no books, could not get any nor did he know where to begin. Time enough for that when he would he discharged at the home port, with a half year's wages in his pouch. It was more entertaining, anyway, to loll on his bunk and listen to the wild tales of adventure, of unrecorded battles, of shady deeds.

He began to feel a real fellow-feeling for the mugs. He well knew now how hard it would be to rise from the stratum into which they had been born and he had been forced by circumstances.

He began to feel a vague resentment against the ranks of the capitalists which he had so recently quitted. It seemed natural to hate them, and also, in a different way, the technicists, whose supercilious superiority rankled in his heart.

They were no better than he! Just luckier. Up there they posed around in their brass and broadcloth, while here below were men, just as good as they, sweating in this filthy hole!

This resentment was a stage he would outgrow, for he knew at heart that the techlicists had studied and worked for their rank. But now he was not backward in sharing his thoughts with the other mugs, and they replied in kind. So it came that Salvader, one of the Rio Blas men, arose from a whispered conference back of a bulkhead and approached him.

"We thought we have to keel you, but now maybe we no need," he remarked pleasantly.

Syl Webb felt a queer little thrill of fear. All eyes were on him not unfriendly, not friendly either. Merely speculative. They were weighing in their minds whether or not it would be advisable to kill him; weighing the question impersonally, calmly dispassionate.

"No, y' can't get out the door," Mark Gunning remarked evenly, interpreting Syl's quick glance. "I got a squizzle." He held up a small ionic projector, whose sizzling beam carried death.

"Well, what is the proposition?" Syl asked calmly.

"You see," Salvader explained frankly, "in ordinar' case, we keel you anyway, but for thees, we need you. For to get by the Interplanetary Flying Police we need man weeth—weeth—"

"Eddication," Gunning supplied? "In two days we hit the outer Saturn guard. Can't none o' us fool them birds. You, Webb, gotta get in the nav'gation room, put up a front—let 'em see y'—talk to 'em over radio."

MUTINY! Such things still happened. Syl found himself accepting the thought equably, but deep within him protest stirred. The fate of the officers was foregone.

"Going to kill the technies?"

"Sure!" Gunning grinned, "We can run the ship. Some of the mugs have picked up a bit, here'n' there. I can read the coordinate tables. We got all we need but a front. You're the front. Wear the Old Man's brass, speak the I. F. P. When we pass the Outer Guard we'll parabola back to the inner lanes. Swing 'round Saturn, y' see, to save power. Then plenty ships, plenty loot, plenty"—he looked around at the glistening-eyed mugs—"plenty women."

Syl was very close to death at that moment. Mutiny, murder and piracy. He had become calloused enough to view brutality with a certain equanimity. But the vision of the girl in the Mars-light by the port came back with a rush, swept away the savage, resentful mists of class hatred with which he had deliberately befogged his mind. Through a red blur he saw the cynical, leering face of Mark Gunning, the circle of predatory faces with their calculating eyes.

As from a distance he heard his own voice, casual, cool: "Uh-huh. And the girl up above?"

There was a roar of laughter, approving, understanding.

"Got your eyes on her already, hey? The gyp's a snaky bargainer, hey?" Gunning grinned, looking back over his shoulder. He took Syl's hand and shook it, his grin changing to a sneer.

"You shall have 'er, fellow," he promised. "After me."

Syl tensed; but he knew his one chance of saving her lay in not resenting that threat—yet.

Admitted to the full counsel of the mutineers, Syl wondered that they should take his acquiescence so much as a matter of course, until he came to realize that in their warped, ignorant morality such action was the most natural in the world. Kill or be killed, eat or be eaten—that was the rule.

He had been spared for the sole reason that he might be useful. That he should purchase his life at the price of a few others was normal. The only sane thing to do, in mug philosophy.

From the very first flash of understanding his human decency had overcome his sympathy for the mugs. His course seemed absurdly simply: merely to report to the captain. Warned, the crew of eight technicists and the two officers' stewards, with the high-powered projectors stored above, could easily overpower the mutineers and hand them over to the Interplanetary Flying Police when hailed by them.

But Gunning was of the stuff of which leaders are made. On Syl's first attempt to edge casually toward the technicists' quarters, Webb was suddenly pricked by keen knife points in four separate places on his back, The Rio Blas men let him feel the keenness of their weapons, then ironically stood aside to let him go back.

"To keel you, mister sir," Salvader purred, "we would regret veree much! Veree much we would regret him!"

Gunning came out of a hold.

"No use yer tryin' to squeal. Or maybe y' wasn't?"

"Of course not! I was just looking the ground over."

"Yeah?" Gunning's beady eyes bored into his own. "Well, y' can find out more in the cabin."

Closely guarded, Syl was returned to the crew's quarters. Strong, thin arm and leg irons were clamped on him, attached to such short chains that he could not lie down in the corner to which they were fastened. On space ships no waste space is available for use as a brig—hence the sleeping quarters are used, and they are bad enough.

Cramped and uncomfortable as he was, Syl's misery was enhanced by the planning of the mutiny. He could, of course, hear every word, and the lecherous references to the lone woman passenger roused him to rage. Yet he maintained his cynical. mocking attitude, hoping they would release him while there was still time. He wondered if he could attract Splade's attention. Splade did not mingle much with the mugs. He would therefore be loyal.

In fact, he soon knew Splade was loyal, for the little Eurasian, Tiang, was delegated to kill him as the signal.

The plan of the mutineers was compact and direct. Bell 23, about fourteen hours hence, was the time. That would be an hour before the changes of the watch. All on the ship would be sleeping except the officers on duty. Tiang, having: killed Splade, was to wait in the galley to answer, after a fashion, any chance call from above.

Gunning, Hoyden and the Martian Tah, were to creep up to the navigating room. Only one officer would be there—Captain Kellerman himself. Epstan, the mathematician, and cocky young Arberson, the chemist, would be sleeping. And four of the powermen.

That would leave two powermen on duty, one on each side of the ship, in the hooded cubicle from which he controlled the propulsion jets on that side. The power cubicles presented a real difficulty. According to the Spatial Acts they must be locked on the inside. Only the captain and the powermen on duty had keys, and even the captain's key would not open the doors. it the powermen set the emergency bars.

The powermen, once apprised of what was happening through their televisor tabs, could cripple the ship and deliver it eventually into the hands of the Interplanetary Flying Police. But because the powermen could he depended on to be brave men, the mug strategists planned to use that bravery.

If Captain Kellerman were murdered, tortured perhaps, wouldn't these brave young men dash out to assist him? A sweep of the hissing projector, in the comparative darkness of the well, would dispose of that question.

THE mugs awaited the fatal hour with grim anticipation, This was a desperate game they were playing. About that they had no illusions. Failure, or discovery by the I. F. P. before they could set up the heavy projectors included in the cargo to be used for the defense of the mines, meant only one thing—and it was unpleasant to contemplate.

A summary court-martial. Then a knot of struggling men, half insane with fear, forced into the airlock. A few seconds of silence after the thud of the inner lock— then to be spewed, instantaneously bloated corpses, tumbling, falling free, oozing blood frozen on their skins—to swing for eternity in their lonely orbit or to plunge into the sun.

Such was the fate of pirates caught in the space lanes, and the mugs, knowing, approached their battle for a well-armed ship and the prospect of possible years of space marauding, with a certain cold ferocity, Syl was never left alone for a second. All of his simulated hope for the success of the mutiny failed to win for him a moment's freedom.

"Y' get yer chance when y' speak the I. F. P.," Gunning told him grimly. "If y' as much as bat an eye—" He touched meaningly the small projector hanging at his belt.

At last the annunciator whined out Bell 23.

As silently as a panther pack of Venus, the mugs faded from the cabin, leaving Syl alone. The door slammed, He tried violently, as he had before surreptitiously, to release himself.

No use.

The mugs were armed with knives, clubs, cargo hooks. Gunning alone had a modern weapon. Treading softly, they started up the well, walking on the sides like flies, for there was no gravity-only the slightly centrifugal force of the ship's axial rotation. Tiang darted out GT the galley, where he had crept shortly before. He whispered excitedly. Mark Gunning grunted.

"Nev' mind. We'll get Splade with the rest, He'll be up there som'rs."

The cabins of the sleeping powermen were unlocked. Furtive figures crept in. A little farther up was Epstau. His door opened, too, letting in the gray light of the well.

The massacre was over in a few seconds. Acting with rehearsed precision, the murderers snapped on the light switches, dispatched their victims while they were still dazzled by the glare. The lights were darkened again, and slinking figures with dripping knives joined their fellows. Arberson happened to be in the chemical room, cursing the leaks. He gave them a game fight, but he was soon overwhelmed.

Gunning listened at the door of Maida Stanley's cabin. She was sleeping, and would keep till later. One cabin door was locked. This undoubtedly held the all-important controls of the heavy projectors. It also could wait.

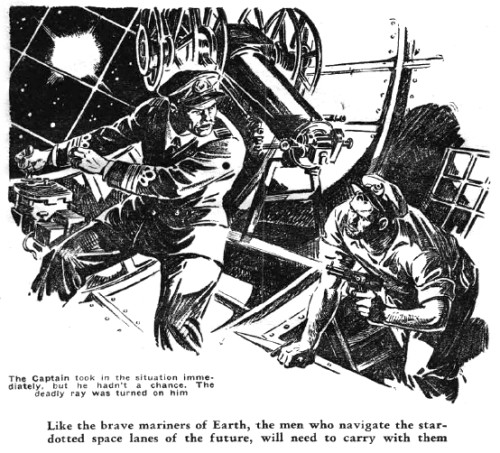

Overhead was the glassed grating of the navigating room. The old man was operating the automatic bearing connotator. Gunning crept up the short ladder. Gently he pushed the grating, swinging it on its pivots.

He had it half open when it creaked slightly. Captain Kellerman jumped up, overturning his chair. He took in the situation instantly, and leaped to the wall for the projector hanging there. But before he could turn, Gunning's beam fell on him. The black hole through his body smoldered as he sprawled on the floor.

Gunning leaped off the ladder to station himself at the well-head, weapon ready. Channing, starboard powerman, leaped out of his cubicle, roaring his rage. He was weaponless, and Gunning cut him down without mercy.

Up above was a slight commotion. Two officers' stewards had been found hiding in a chest, and several of the mugs, amid much laughter, were dragging them to the airlocks, along with the bodies of the murdered technicists. Fearing Gunning, no one had touched the girl. Her white, frightened face had appeared at her cabin door for an instant. Then she had locked herself in.

But Helgrim, the port powerman, was not only brave—he was prudent. He saw the murder of Captain Kellerman on his televisor tab, and like Channing, felt the impulse to dash out of his locked cubicle. But unlike Channing, he had been a mug himself before his long, arduous climb to his present position. Many mugs could operate the power generator, but few had Helgrim's shrewdness that enabled him to break into the close corporation of the technicist guild.

Instead of following his impulse to dash to the rescue, he paused with his hand on the lock and listened. A few moments later, faintly hearing the noise of the triumphant mugs, he took a long chance. He threw the port jets into full reverse.

It was a foolhardy thing to do, only justifiable in this extreme emergency, for the tremendous strain might easily have carried away the port vanes, and the power cubicle, too.

Under the terrific reaction of the electronic blast, in which millions of horsepower was expended in a few seconds, the huge ship flipped over and over, Before he could remove his hand from the control, Helgrim was thrown against the roof of his cubicle, His desperate grip was torn loose, but just before he lost consciousness he saw a blinding flash. The activator fuse had blown.

Immediately the ship's automatic course director took charge again, the auxiliary circuit taking up the load, and brought the Pleadesia back on an even keel, But Helgrim's desperate expedient, as he had hoped, seriously disorganized the pirates. As they had all been in the forward part of the well, with nothing at hand to hold on to, they had been flipped about sixty feet, to land in a heap against the upper grating. Salvader's skull was crushed, and some of the others were badly injured.

Cursing, and reckless in their rage, they began to assemble one of the heavy projectors to burn down the port power door, battering down the cabin doors in their search for the parts. They were risking everything to gain speedy control of the ship, for they might very easily breach a hole clear through the outer skin, letting their precious air escape into space.

HELGRIM'S forceful methods had done more than the mugs knew. They had shaken out from his burlap bales in the hold next to the galley a rather thin elderly man with graying hair, weak chin and pale blue eyes. Splade had taken leave of his work before the regular time, and had been wafting gently among the airy fantasies of a merclite dream.

Weaving on unsteady legs, he started up the well toward the lighted grating some three hundred feet away. He saw, or thought he saw, hurrying figures, and heard a great deal of noise.

He was almost within the lighted area when he bethought himself of his condition. Guiltily he started back.

"Mus'n' let a tec—tec—technie see me like thish! Get a ticket for it, prob'ly."

A moment later, as the ship yawed in a course adjustment, he was thrown of his feet and tumbled a dozen yards further toward the base.

"Must've chewed too mush! Yes, sir! Man shouldn't chew too mush! Never made me feel like thish before. Rotten stuff they're selling us nowadays!"

Communing with himself, he brought up at last against the dirt-encrusted base of the long cylindrical hull.

"Hanged'f it don't 'make me hear things!" he exclaimed then, for he thought there had been a call for help beyond the metal-studded door of the crew's cabin It sounded like Syl Webb's voice.

Weak rage flared up in him.

"Nice boy!" he croaked. "If them so-and-sos are horsin' him!" Fists raised in what he believed to be a pugilistic attitude, Splade kicked open the door and staggered in.

Leaning against the wall to which he had been chained, Syl looked as if he had been horsed very much indeed. There had of course, been no opportunity for him to be thrown as the mutineers had been, but he had been viciously shaken, and the blue light disclosed the ghastly pallor of his face. At Splade's appearance, however, a flush of joy overspread his features.

"Splade! Get a key and take these irons off me!"

Splade blinked. "Let me at them mugs!" He milled around with his fists.

"Splade!" Syl strained at his chains. "You fool! They're murdering the technies! And the girl's up there. Get a key—take these things off."

The cook finally saw his friend, tried to bend over him, fell on him instead. Syl heaved him off impatiently. But Splade's senses were slowly rallying. He drew a hand across his eyes.

"The key, huh,"' he muttered. "Gunning's got it. I'll get it from him."

"No!" The younger man drew heavily on his newly learned mug profanity. "You'll get knifed. Find a chisel and a hammer. Cut the chain. Understand, cut the chain!"

Splade shuffled out to the tool room. He returned presently with a maul and chisel, and proceeded to cut one of the chains. Although the metal was light, hardly more than wire, it was very tough and time seemed endless before Syl's arm was free save for the light metal cuff. There was the ever present danger that one of the mutineers might come back.

Syl wielded the maul after that, Splade holding the chisel, and under the former's purposeful blows the three remaining chains soon lay on the floor. A moment later, through the half-open door, they heard footsteps.

"QUICK!" Shoving the shaking Splade into one of the higher bunks, Syl leaped up to the next one. Here they were a couple of feet over the heads of men standing in the room. They were barely in time, for four of the mugs crowded in.

Foremost was Wannol, his wainkled bronze head flecked with tiny specks of blood. Behind him were Tweedy, a rat-faced little renegade from the Clyde, and two coppery, coarse-haired Indians who were naked save for torn strips of gold braid ripped from the murdered technicists' uniforms. Blood-lust glistened in the eyes of all.

"Says it's under the bottom bunks," Wannol rumbled. "Get under there, you swabs!"

The others started to haul out a heavy coil of insulated cable. But in a moment Tweedy snapped defiantly upright.

"An' who are yew to order us 'round?" he rasped.

Wannol advanced ominously, his enormous shoulders hunched. Tweedy, who had seen that look before, blanched. His hand slipped furtively to his belt, to the hilt of his curved thin-bladed knife. But Wannol, like a human avalanche, enveloped him. There was a dull crackle, a relaxed sigh, and the limp body of Tweedy sank to the floor. Wannol contemptuously plucked the knife out of his fat shoulder and threw it rattling on the floor plates.

"Now!" he growled looking at the Indians.

With little trace of their traditional stolidity they bent their backs to the load and staggered out of the door.

Wannol started to follow them, when his glance suddenly rested on the severed chain ends.

It was some seconds before his slow brain functioned. He glared around and then his red-rimmed opaque brown eyes fell on the crouching form of the missing prisoner. With a bellow he charged, his terrible arms upraised, his inhumanly powerful hands clutching, talonlike, for the kill.

But they never closed on their victim. Syl balanced himself on the edge of the bunk, drew up his powerfully muscled legs, and at precisely the right moment let drive with all his strength. His heavy-soled work shoes struck squarely in the bronze-mottled face of the man of Venus, with all the power of his clean young body now tempered and hardened by labor.

The blow did not kill Wannol, for he was extraordinarily tough, but it stunned him. Syl tied him with a short length of cable that the Indians had overlooked. Then he looked out into the well.

At its forward or upper end he saw knotted around a squat contrivance mounted on skids, with a large tube, the counterpart of the small hand projectors.

Syl guessed correctly at the reason for his recent shaking up. The brave powerman was shortly to be burned into eternity.

At that moment of realization a plan sprang full-grown in Syl Webb's brain. A plan so utterly hazardous and foolhardy that the best he could hope for if he succeeded was death—a swift and merciful death. for himself and the girl.

SWIFTLY and efficiently he stripped Tweedy's body of his gaudy orange fibroids. Picking up Tweedy's knife he plunged into the well, ran swiftly toward the lighted part where the big projector was ready to start. Those who glanced at him thought he was Tweedy, for the light was poor and their minds were on the projector.

Gunning sighted, set the intensity control at low. Back came the lever. With a roar like a giant blowtorch the projector threw its powerful beam against the metal door of the power cubicle. In a few seconds though it was heavily armored, that door would crumble like a rag. The mutineers involuntarily retreated a few paces.

As they did so a figure separated itself from them—a figure in gaudy orange fibroids. Swift as light the narrow blade leaped in, straight to the lever slot in the control box, slashed into the delicate maze of platinum wires. There was an instantaneous flash, and a ball of fire leaped out. The tube glowed white, collapsed.

Gunning and Syl had both leaped to safety.

"You've killed us all!" Gunning roared, snatching out his hand weapon. He pointed it at the supposed Tweedy, but sheer amazement halted his finger on the button.

"So! You!" His weapon flashed—a puny beam compared to the heat of the self-destroying great projector. The heat was intense in the confined space. Syl had not been hit. His jump had carried him to the forward side of the scintillating mass, and the mutineers could not even see him.

Back of him a door opened. The heat, penetrating the walls, had driven the girl out. There was a slight bruise on her temple. Her face was pale, but she faced death with the courage of the finely bred.

Syl threw off his cap, and wiped his grime-and-sweat-streaked face with his sleeve, She recognized him, gave him a brave smile. With true instinct she guessed the facts of the present situation, She offered no resistance as he led her up to the grating into the deserted navigation room.

That inescapable inferno would never stop until the proton container was empty. Long before then the ship would be but a globe of molten metal.

"The controls are shorted," Syl said gravely to the girl. "No human being can get close enough to throw the switch. You know what that means."

"Yes." There was the barest possible tremble in her voice as she looked him full in the face.

Unpremeditatedly, reverently, his arm went around her lissome waist, and he kissed her once on the upturned mouth. Then he would have released her, but she clung to him, pressed her body against his, so that the delicate fabric of her robe was soiled by the grime of him.

"We have only a few minutes to live," she whispered "I have thought of you often since the day you spoke to me, though you frightened me. Hold me."

They moved over to the wall, where the terrible cold of space relieved the acrid heat pouring in through the grating. The howl of the mutineers came to them.

"Animals!" exclaimed Syl Webb. "They fear death. They cannot die bravely."

"Who says 'brave'?" The face of Mark Gunning appeared over the floor edge. He was a horrible sight, Nearly all the clothing was burned off his body, the hair was scorched from his head. He was a living cinder. His cracked, baked skin smoldered and gave off a sickening odor. His sneering face, shockingly seared beyond human semblance, was the face of a damned soul rising out of hell.

"Who says 'brave'?" shouted Mark Gunning. He held up his right arm, charred off at the wrist. "See that? Me, Mark Gunning—reached in there and turned it off! Stuck my bare arm into the melted metal 'n' turned th' bar. Who says 'brave'? The woman's mine!"

"He's dying," Syl murmured aside, "He can't last. He'll drop dead in a minute."

But the mug leader's immense vitality would not let him die, Eyes glazed, he stumbled about the room, vainly looking for the girl. The other mugs, however, saved from death by Gunnings superhuman bravado swarmed up the ladder.

SYL, quick to avert the new danger, seized the girl and drew her up the metal rungs to the peak of the chamber, under the emergency exit cap. His hand grasped the lever.

"Fire, or come one step closer, and down comes this lever. Know what that means? We'll all pop out of here like a cork out of a bottle. Understand? One step closer and we're all dead men!"

The mutineers understood. They cursed, they blasphemed, but they dropped their weapons. Their slow retreat became a panicky scramble as Syl, shifting his weight, rested his hand too heavily on the lever for a moment, accompanied by the hiss of escaping air. It mattered not that the same fate probably awaited them as soon as the I. F. P. ships appeared. They cringed before him now in a mute plea for a few hours more of life.

But death, approaching fast for Mark Gunning, granted him a brief respite. His filming eyes cleared, and he saw Syl Webb and the girl. With agony in every movement, he stooped to pick up with his remaining hand one of the projectors dropped by the mugs. Slowly, with infinite effort, he raised it until it was pointed straight at Syl.

At that moment a knife flashed through the air from the group of frightened mugs and buried itself deep in Mark Gunning's throat. As he slipped slowly to the floor, the dark red blood started dripping off the knife handle.

The abject mutineers rushed forward, threw themselves on the floor.

"We surrender!" they chorused.

Syl's voice was edged with disgust.

"Put the weapons back in the rack, and see they're all there. Then get out!"

He kept his hand up until the last man had taken his hasty departure. Then he held out his arms and Maida slipped into their embrace.

But in both of them was a primitive respect for sheer bravery; and when Splade came in, quite sobered, a few minutes later, and started to haul away the charred body of Mark Gunning, a mutineer but a man of courage, they stopped him. They covered the corpse with a synthetite drape torn from the wall, before letting the cook bear it to the airlock. Not until, a few minutes later, they heard the dull thud of the lock's closing, did Maida's arms go around her lover again.