Help via Ko-Fi

ACCUSTOMED as we are to our world in which the laws of nature are well-known to us, we are apt to forget that what seem to be absolute laws are really only approximations. Since cause and effect seem to follow with precise regularity, we construct from them laws of nature.

The truth is that our laws of nature are just convenient explanations of things. But it is possible that the real and ultimate laws of the universe might be very much different than we imagine. Our universe might stand in the same relation to the universe of reality, as the universes of microscopic creatures stand to us. As Alphonse Berger said, writing in Candide (Paris) recently, "By the side of the microphysics of the infinitely little, we have a cosmophysics of the infinitely great. And beyond? May not our universe itself, huge as it seems, be for some vaster being nothing but an aggregation of molecules, of which each is a solar system? What unimagineable physics must govern the movements of the vast solid made up of such units? But is it not fine that the brain of man is able to rise to the height of such thoughts?" The present story dealing with this theme is one of the most unusual we have read.

ABOVE the subdued din around the dinner-table wherein the fashionable evening clothes of the day were gathered all white people worthy of note in Cairo, could be heard the dictatorial voice of Mr. Parling, the mathematician. Broad-shouldered, stout but not fat, with legs set wide apart like the Colossus at Rhodes, he dominated the company and delivered his speech with the gusto and rhetoric of an orator. He was s perfect type of dinner guest. He would emphasize a point of his discourse with a blow of his fist on the table which threatened to spill the wine.

Opposite him with glowering eyes sat Dr. Klington, philosopher and amateur archeologist. His lean hard frame, long ascetic features, and hair of the colour and texture of fine copper wires, were in utter contrast to the appearance of the speaker.

For more years than either of them would care to admit, they had waged a wordy War, mainly through the medium of the press. Few were the scientific controversies in which the one participated without the opposition of the other, and now for the first time they had encountered each other in person. The guests who were "in the know" smacked their lips in anticipation.

Their amiable host had realised too late and with a deep sense of chagrin the the trouble he might cause by inviting them both to the same dinner. He trembled at the thought of the con-sequence of this tactless act. What nonsense was Mr. Parling saying now?—

"...and it is my firm opinion, based upon irrefutable theory, that our universe is composed of a great number of three-dimensional worlds existing side by side in a fourth dimension, just as the two-dimensional leaves of a book lie side "by side in a third dimension.. "

Mr. Parling droned on while the host wondered if his new social idea of allowing everyone present to speak upon his own special subject hobby was as good as he had first thought it. His mental peregrinations were suddenly terminated by the sound of a low, highly-cultivated, insistent voice; the inevitable had happened at last. Dr. Klington had interrupted the thread of Mr. Pauling's discourse.

"I beg to question that latter statement of yours, Mr. Parling. Such an utterly absurd idea can have no foundation when opposed by the doctrines of the very keenest brain of the last century, I mean the eminent and profound scientist, the Frenchman Henri Poincaré!"

"Henri Poincare! He was a mathematician, yet he was also a philosopher, and like all philosophers he was a dreamer!"

A buzz of excited voices swept around the table for this was a direct attack upon Klington.

Developments after that threatened to depart from a mere discussion and become a brawl, in which the excited guests did not hesitate to join. The affair promised to be a welcome relief from the boring speeches which had hitherto marred the evening. Mine host's voice was heard occasionally above the tumult, pleading but futile, "Now, gentlemen, do be a little more quiet, please!"

Events were brought to a sudden silent standstill, broken only by faint whisperings, by the booming voice of Parling. "Stop!" he cried.

"Dr. Klington," he said in a quieter tone now that silence had been restored, "would direct experimental evidence convince you of the truth of my assertion?"

Klington smiled sarcastically. "It certainly would."

"If you care to call at my bungalow tomorrow morning I shall be pleased to offer you such evidence."

* * *

Klington did not fail to keep the appointment. He was let into the bungalow by Parling himself. They were both a little stiff and cold in manner as they walked to the sitting-room and Klington haughtily took a seat.

He was instantly aware of a strange sweetish aroma which faintly prevaded the atmosphere of the room, but on looking around he could not see its source. His antagonist stood before him in the characteristic Rhodian attitude, legs wide apart, and began to speak.

"You probably know that the firm of constructional engineers for which I work is at present building a dam across the White Nile in order to facilitate irrigation."

The philosopher nodded assent.

"While excavating for the foundations on the bank of the river, the workmen came across a sealed chamber hollowed out in a rock face, and within the chamber was discovered a sarcophagus. It was temporarily transported to my bungalow, en route to the British Museum. There it is, behind your "chair."

KLINGTON turned his head and perceived the origin of the odor. It was a stone burial receptacle of the usual type. An inspection of the interior showed nothing more startling than mummified remains and a scroll of some material, probably papyrus, with an inscription on the outer surface.

"I understand you know something about archeology," said Parling. "Can you tell me what these hieroglyphics mean?"

"Certainly. Hum. This is rather strange. It means—Before Isis existed this was. Very peculiar. But what has this got to do with the question?"

"You will soon see."

Parling took the scroll, unrolled it and revealed within a flexible bar of some bright purplish material, about three feet long and two inches wide. One end of the bar was fitted into a small transparent globe containing a yellow liquid. The bar could apparently slide right through the globe, a groove having been made for it.

Parling had assumed a confident overbearing manner and the light of triumph was in his eye. He pushed the rod till the end projected about four inches beyond the other side of the globe.

"I found it entirely by accident," he said.

"Found what?" said Klington, manifestly puzzled and a little contemptuous.

"The secret, of course," said the other. "Now watch the end of the bar carefully."

With these words he continued slowly to push the rod through the bowl. And then it was that Klington began to think he was being hypnotised. He could no longer see the end of the rod. Up to four inches from the bowl there was firm solid matter, but beyond that, nothing!

Parling chuckled at his astonishment.

"You're wondering where the end of it has gone, eh? Well, you see it's perfectly flexible? Just where it ends off it has undergone a double right-angle bend. And through some unique property conferred upon it, no doubt, by the presence of the liquid in the globe, one of those bends is in the fourth dimension. The other bend naturally brings it into some other world parallel to our own. It certainly is not in our world,"—and he passed his hand through the space where the missing end of the bar would normally have been. "I defy you to explain the phenomenon in any other way."

Klington was decidedly sceptical. "How do I know you are not tricking me?" he said.

Parling scowled and thrust a finger before the other's eyes. It was stiff, lifeless and almost brittle.

"See this finger? I had placed my hand on the rod and moved it along towards the vanished end in order to attempt to follow the bend into another world. I succeeded!—to my cost. The chances against the other end of the rod being on the surface of a planet were billions to one, so it is not surprising that my hand emerged into the frightful cold of the outer space of some other world. I quickly withdrew it, but the result is as you see."

Klington's lean face showed a curious mixture of expressions as doubt struggled with conviction. Parling was speaking again while he clamped the rod and globe to a mechanism on the table.

"With the aid of this vernier arrangement I can project the bar along the fourth dimension any desired distance correct to a ten-thousandth part of a centimeter. I rigged it up this morning in preparation of your coming. In order thoroughly to convince you, I propose we make a journey into one of the many universes parallel to our own. Is your philosophic courage equal to such a trip?"

There was only one answer which a man like Klington could give to such a challenge.

"But how can you be sure that the world we enter will be hospitable? It is not just necessary to land on the surface of a planet; it will have to be moving at about the same rate as ours and in the same direction, or else it will be impossible to transfer from one to the other. Also, of course, the correct atmospheric and temperature conditions will have to be found."

"That's easily arranged. Nothing simpler. We'll first of all fix the end of the bar at a certain distance and slide a thermometer along it, and other instruments of course such as a barometer, a container to get a sample of the air to be analysed, and a camera to see how for from the surface of the planet we are. That universe not being suitable, we'll simply alter the distance by means of the vernier and try another. Shall we start now?"

And so they began the hunt for a suitable cosmos. Klington very soon lost the last traces of doubt, and the two men forgot all their former antagonism in the common interest of the search. They became, in fact, as enthusiastically excited as a couple of schoolboys.

The method adopted for projecting the thermometer along the fourth dimension was at once ingenious and simple. A loop of cord was passed round the rod and attached to the instrument; with the help of a close-fitting flexible sleeve around the bar the thermometer could easily be pushed along it without the hands of the operator coming in contact with the other world. Since the thermometer was bound to the bar, it was forced to follow the bend into the fourth dimension. Other objects were treated similarly.

In all the first few attempts, the mercury in the thermometer was frozen solid. After a week's work they found a small piece at the end of the bar was melted clean off. Apparently the last attempt had projected it into the interior of a sun.

By this time the sarcophagus had been removed, but Parling secretly retained the purple rod and globe in order to continue the experiments.

At last they discovered a world whose temperature was quite tolerable, only eight degrees Centigrade. Disappointment awaited them on analysing a sample of the atmosphere, however. An uncomfortably large percentage of chlorine was present. But this did not deter them. Klington suggested obtaining gas masks with small tanks for liquid oxygen. On taking a photo with a clockwork-shuttered camera weighted so as to swing the lens towards the centre of gravity of the new world, a firm greyish ground was perceived about forty feet away, with long slender black stems growing ten feet high and five yards apart. The clearness of the print indicated that the ground was almost at rest relative to our earth.

Having obtained a rope ladder, they came to their final difficulty. The flexible bar could not possibly hear their weight. This was overcome in the following manner:

All the ladder except about a foot of one end was projected into the outer world. The visible end of the ladder was then fastened to a stout stanchion in the wall, and disengaged entirely from the bar.

The vertical in the other world was inclined at an angle of thirty degrees to that of the earth. To transfer themselves from one world to another, all our dimension-travellers had to do was to grasp the visible rope of the ladder, feel along it with their hands till they came to the next invisible rung, grasp it, and pull.

A fortnight after their first meeting all was ready for the journey of exploration they intended. They donned their masks with eager haste, strapped on haversacks containing a fortnight's supply of food and also oxygen tanks, and attached leaden weights to their feet in order to counteract the effect of the small amount of gravitation in the new world.

Parling stood by the ladder. "Are you ready?" he enquired of Klington who nodded, too excited for words. Parling fumbled about for a moment with invisible hands for ‘the invisible rung, gave a tug, and vanished silently.

After an instant of hesitation, Klington followed.

CHAPTER II

The New World

THE first sensations Klington experienced were the change of direction of the pull of his weight through an angle of thirty degrees, and an immediate drop in temperature As he clambered down the ladder swaying with the motions of Parling below him, he became aware how necessary was the thick coat he had brought with him. Rung by rung he advanced towards a land never trodden before by earthly feet. The chlorine gas present in the atmosphere, though not sufficiently dense to prevent distant vision, gave to everything an unearthly green tinge. Shortly the tops of the forest of black stems became apparent, and he observed that the tip of each stem branched off into several short and pointed spikes.

A few more rungs, and with a thrill of anticipation Klington stepped from the ladder to the ground. Vision was remarkably clear except for the upper heavens which were blotted out completely with clouds of green.

The widely separated black growths offered almost no obstruction to the view. The ground was pitted with innumerable straight deep ruts, varying in width from eight to ten feet, and leading in every direction. Where two ruts ran together, there occurred a circular pit whose depth could not be estimated owing to the jet blackness of the interior.

Some indefinable quality of strangeness about the landscape seemed just to be eluding his attention. Something was puzzling him, and he could not locate it, something that was entirely differentiated from anything he had previously experienced. His confused mind groped as if in blindness; be turned to express his bewilderment to Parling, and found him closely examining the nearest black hole.

Its texture was smooth and glossy, its width a mere inch, surprisingly thin for such a length, and every few seconds it quivered gently. Were they plant growths? If so, they had no terrestrial counterpart.

Parling cautiously put out his hand and felt the velvety surface. With a cry of affright he recoiled suddenly, but loo late. The thing gave a sudden tremor and lashed about with irresistible violence. Parling was instantly flung off his feet and precipitated over the edge of a circular fissure behind him!

Klington rushed to the hole and peered over the edge. Nothing was visible but he heard a curious slithering sound,—and a despairing voice.

"Quick, Klington, for God's sake help! I'm on a kind of slippery ledge and I can't hold on much longer!"

Now the ladder was a hundred feet long in case by chance this new world they had entered moved away relatively to the earth. With great presence of mind, Klington flung the loose end into the pit, and held it firm while Parling clambered up, none the worse for his scare.

"Phew! What kind of a plant is that? Was that a reflex action?" said Parling. "That darkness has reminded me. Wait here a minute."

Parling climbed up the ladder and vanished into the world of their birth, shortly reappearing with two electric torches remarking that they might require them. Despite all of Klington's philosophy, he could not forbear a twinge of uneasiness as he waited along in this world of unknown perils. Suppose Parling, prompted by their former antagonism, pulled the ladder back into the bungalow, leaving Klington stranded? But Parling's immediate return put his thought to shame.

All was now in readiness to start a tour of exploration. Before they left. Parling attached a large white sheet to the top portion of the ladder, to serve as a guide on their return journey. Then from a point half way up the ladder the surrounding land was surveyed to determine the direction they should take.

"Notice anything peculiar about the horizon?" asked Parling.

That was it, the horizon! It was that which had been puzzling him! There was no horizon! The desolate plain on which they were situated moved upwards in front and behind and on the right in a great concave sweep,—and never ended. It continued on and on, mounting higher, until hundreds of miles away it was lost to view in the green mists of the sky. Only on the extreme left was there a short semblance of a horizon, where a definite edge could be seen. This was assuredly no ordinary planet which they were visiting. There was no sun in the heavens, but a brilliant glow on the left, which lit up everything clearly, seemed to proclaim the presence of some solar body below the brief horizon.

PARLING discerned a mighty chain of mountains on the right almost having the appearance of hanging over their heads, about fifty miles away as near Es could be judged, and it was towards these that they finally decided to make their way.

With their rifles and a plentiful supply of ammunition, they set off. Walking was by no means difficult; the fissures were easily cleared at a step owing to the fact that the leaden weights were insufficient completely to supply the gravitational deficit, and it was simple to avoid the widely spaced stems. They covered about twelve miles without a single mishap or an encounter with any inhabitant of this desolate region, and then called a halt for a meal.

Perhaps it should be explained that the masks Parling and Klington were wearing were quite different from the type used in the Great War. They permitted free movement of the mouth and were adjusted Ill a moment.

After a short meal the march was resumed, and within an hour they emerged from the forest of black boles and found themselves on a gently sloping plain,—tirely free of fissures and of a much harder, though not rocky, character, which led directly towards the foot of the mountains.

These latter far surpassed any earthly heights, and formed a tremendously awe-inspiring spectacle. Composed of a dazzling smooth white material, they rose sheer in an absolutely vertical line from the plain to s height of at least twelve miles.

Imagine the confoundment of our little terrestrials at this breathtaking revelation. Consternation, dismay, terror, admiration, seized them in turn as ‘they gazed upon the glorious albous magnificence of those sharp peaks crowned in green mists. In perfect order they stood, in a straight line, all of similar shape, like a line of guards shielding the mysteries of the land beyond. Broad at the top as at the bottom, many overlapped or were in actual contact in parts, and at most only a narrow crevice separated them. Each peak was of a uniform width of four or live miles, and seemed exceedingly thin (as measured in the direction in which the travellers were going) for their height.

Parling and Klington pushed on rapidly across the plain with burning curiosity to discover the secret of those celestial crags. What manner of world was this in which Nature was so lavish, and so—regular?

Such was the slightness of gravity that by the time (as indicated by Klington's watch) Cairo was in darkness, they were but a mile from the nearest peak. Speechless with astonishment at the close view of the monstrous mass and weary with exhaustion, they struck camp on the plain and composed themselves to sleep. All this time the brilliancy of the illumination had neither diminished nor increased.

Parling was suddenly awakened by a hissing whisper from Klington.

"Parling! Sh! Lie quite still and on me what you hear!"

A moment of silence.

"Not the slightest sound!"

"Put your ear on the ground, then."

"Yes! Yes! A faint thudding sound."

There could be no doubt about it. Every thirty seconds a distinct booming noise was heard, and—was it imagination?—the ground appeared to rise and fall gently at each noise? Did this portend the approach of some unknown danger?

Attacked!

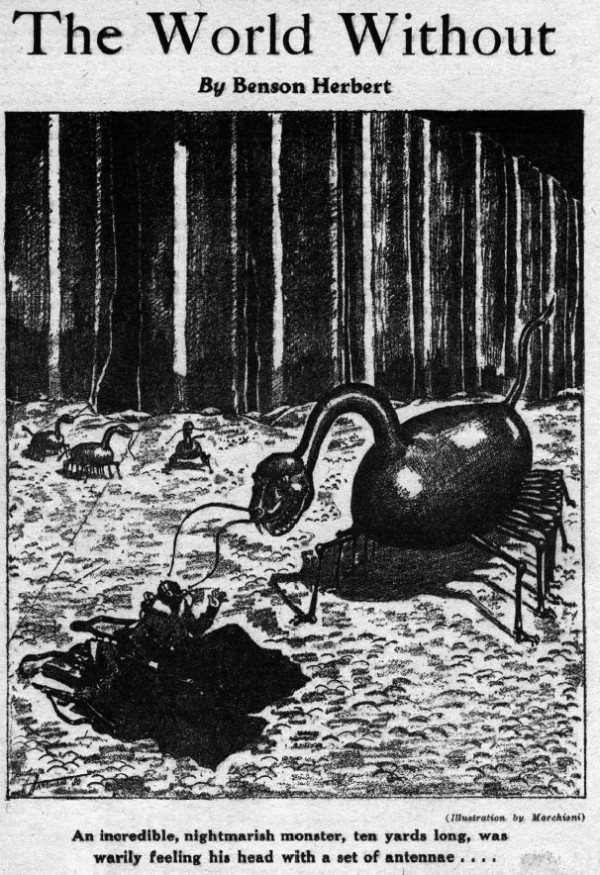

BARELY had they fallen asleep again when Parling was aroused by a peculiar sensation on his brow. He opened his eyes and started up in horror, unable to utter warning to Klington, his vocal cords momentarily, paralysed. An incredible nightmarish monster, ten yards long and with ten spidery legs on each side, its head set on a long thin arching neck, was warily feeling his head with a set of antennae emanting from the place where its nose ought to have been!

Parling stumbled over Klington, instantly awakening him, obtained his rifle and fired haphazardly. The Stygian beast immediately turned and galloped with tremendous velocity towards a crevice between two mountains, and vanished. The two men gaped for a full minute before recovering their wits. Then Klington spoke, shakily.

"Well that's the first sample of Otherworld animal life we've had, and if the rest are like that, we shan't have to protract our visit too long!"

After that, one watched while the other slept. The lack of fuel was much regretted for the cold seemed more intense when lying still.

At six A.M. Cairo time they prepared to set off once more. Parling stood up and faced Klington.

"We have a choice before us," he said. "We can either return at once to the ladder or continue to the other side of the barrier through the crevice, where we will meet heaven knows what perils. For myself, I am extremely curious to discover what lies behind that white wall, but seeing that the object of our expedition is accomplished, namely that you are thoroughly convinced of the truth of my theory, lam quite willing to retrace our steps if you do not care to proceed."

Klington's answer was brief and to the point.

"I move that we push on at once," he said calmly.

That settled the question. In a few minutes they were at the foot of the nearest mountain and examining with great wonder the smooth polished surface thereon. The wildest imaginings filled the brains as they surveyed the colossal structure.

"Surely this must be artificial," said Parling in an awed tone, as Klington tested its hardness by kicking it.

"An artificial barrier ten miles high is quite incredible," retorted Klington.

"Nevertheless we have seen many incredible things in the last few hours. It is my opinion that on the other side we shall find the builders of this wall. Think what a tremendous degree of civilisation they must possess for their engineers to construct such a huge barrier!"

Before he could theorize further the two were fighting for their lives. A horde of creatures similar to the one previously seen, were rushing down upon them from the mountain pass. Useless to flee—they were galloping along at over two hundred miles an hour. The terror of despair gripped the hearts of the Terrestrials as they fired into the midst of the advancing mass. As if by magic, the leviathans instantly dispersed to all sides and sought shelter. It was apparently the sound of the explosions that they could not withstand.

Frequently in their journey through the pass the travellers were attacked by these horrible denizens of the mountains, but noise never failed to frighten them off.

The way through the pass was rough and difficult. Often Parling and Klington could barely scrape through between the two crag-sides. The path moreover was steep and rose to an elevation of several hundred feet about half-way and descended as steeply on the other side. if it were not for the advantage of lesser gravity they could never have performed the feat. As it was, over five hours were required to pierce to the other side. The latter portion of the journey was beset with dangers owing to the increasing slipperiness and unevenness of the road.

Then at last their arduous trouble was rewarded. They safely maneuvered a tortuous gully, wedged themselves through a narrow cleft, and came in sight of the concealed domain behind the barrier.

CHAPTER III

Where Red Ruled

THE most striking thing about this new territory was the fact that every object in it, except the cliffs behind. was red. A great red plain stretched before the daring Terrestrials, traversed by numerous folds, and covered with a low, red, bushy vegetation in which swarmed a myriad forms of almost microscopic life not unlike mundane insects—but all red. Each step they took a squelching noise and a red viscous ooze emerged in slow trickles from beneath the vegetation. Several miles away from the cliffs the land appeared to he in deep darkness.

Of Parling's anticipated mighty civilisation and great engineers, there was to his keen disappointment, not a single sign. He still hoped, however, that they might live underground, or else how to explain the regular beating sound they had heard on the grey plain, apparently emerging from the bowels of the earth?

While Parling was cogitating thus, Klington suddenly became alarmed and, seizing his pair of binoculars, he stared intently through them vertically upwards at the green sky.

"Parling, look straight up," he said tensely, "there's a vast white thing falling through the green clouds!"

Parling, extremely startled, looked up also. Were his senses playing him tricks? Had his mind given way under the strain of the recently uncanny happenings? If so, how did it come about that Klington's illusion was the same as his? The appearance took the form of a line of huge white cliffs hanging upside-down in the sky at least fifty miles away, and falling straight towards those other cliffs below, which they so greatly resembled. He was also conscious that the illumination which up to now had remained steady, was gradually fading. What could this new development mean? Were they to be plunged into darkness and crushed helplessly beneath countless tons of rock? And where was the rock falling from? A sudden fantastic thought entered his tortured mind, almost too bizarre for utterance.

"Klington," gasped Parling, seizing him fiercely by the arm and slowly pointing upward with the gestures of a fanatic, "Klington, it is as if—as if a colossal mirror were falling above our heads, and what we are seeing is the reflection of the white ranges we have just passed through!"

Indeed, Klington readily imagined that one was the reflection of the other, so alike were they in every visible detail. All at once he sprang to life. "Come," he said, and spun Parling round, "we have no time to lose. If the apparition is really a rock falling from an immense height, it will take over an hour to reach the ground. We required five hours to pierce the pass; to return is therefore foolhardy. Only one way lies open to us, and that is directly across this red plain away from the mountains. It is our only hope of life. We must flee as far as possible from here before the catastrophe occurs! Come!"

And the two dispensed with some of their leaden weights and began to run across the red ooze in mighty leaps of fifty yards each. The seeming utter impossibility of what they had witnessed had staggered their minds; all logical connected thinking ceased; a dull apathy settled upon them, and only the motor centre of their brains kept their leg muscles in feverish activity. Onward they progressed in Herculean strides; they did not even dare stop" for meals, but ate as they ran.

No word, but only unpleasant squelching sounds, broke the silence; they reserved all. their breath for running. Ever the light continue to fade, ever they approached the dark shadows of the farther side of the plain. But what was the use of their flight? Such a mass crashing down from the skies would shake the whole planet to its very foundation. Anything was better than inactivity; to stand still and watch an awful doom approaching would have been inviting madness. Often Klington and Parling wondered if they were not already insane, and undergoing illusions rivalling those of an opium dream.

SUDDENLY they were both flung on their faces by a terrible continuous cracking noise interspersed with frightful peals of thunder, as if Thor were splitting the earth in twain with his hammer. They were unable to do anything but cling hard to the vegetation and stare at the monstrosity in the heavens while the medley of sounds accompanied by a terrific blast of hot air swept over them. Had the falling rock at last reached the ground? But no! They goggled in their amazement. The line of rocks, now only half a mile from the topmost peaks, were no longer accelerating but were actually slowing down! Their speed now was reduced to not more than a few feet a second.

Whence then came the awful sound and the wind? The last vestige of reality left the scene as the lone human beings stared about with frightened eyes and failed to perceive the origin of the dread tumult. There was a vague mass faintly in sight far away to the left, and shadowy outlines above in ‘the skies indicated something huge like a canopy as if supporting the suspended rocks. The light, now reduced to a mere dim twilight, gave them no cheer. They had been saved for the nonce by a miracle so incredible that their benumbed wits had not as yet even realised the situation.

Then as suddenly as it had begun, the deafening din ceased, but the warm blast continued blowing, without noise, and left the world once more a wilderness of silence. The men staggered to their feet and found that they were just within the region of dense shadow they had perceived before. Seeing that all immediate danger was apparently over, they decided to recuperate their fatigued bodies with sleep and food.

Parling was the first to awake. While his fellow-voyager slept on, he occupied himself in throwing away an empty oxygen tank and replacing it with a full one.

An Unexpected Peril

KLINGTON was aroused from his deep sleep by a light touch on his shoulder. He opened his eyes, stared upwards at Parling, and grunted interrogatively. Parling had unconsciously assumed the old familiar attitude, legs stiffly apart like a statue; his arm outstretched pointed over Klington in the direction of the white mountain-chain. "Look," he whispered. The other slowly got up and turned around. The two simply stood and watched, absolutely incapable of further wonderment, while the new danger rapidly advanced.

A wall of some liquid, apparently water, at least a mile high and so long that it stretched out of sight on either hand, was bearing down upon them with the velocity of a tidal wave. With one accord they turned and fled into the darkness.

They soon found themselves going steeply downhill, and it became so black that it was necessary to use the torches. The latter saved them from countless mishaps as they sped through the gloom in gigantic leaps. Their velocity was now almost equal to that of the oncoming wave, but how long would it be before they tired and their doom overtook them? They were now practically "falling down the precipitous grade, and making good progress, but while the slope no doubt aided them, it also speeded the water behind them. The swishing and roaring of its passage had just become audible when the ground suddenly smoothed out to a gentler slope.

Gasping for breath, they raced on side by side, and ever as one stumbled, the other tarried to help him up. After many weary miles were covered in this manner, their overworked muscles were forced to slow down. Not so the waters, however, which inexorably swept on. The latter could no longer be seen, owing to the dense blackness, but their nearness was easily judged by the increasing noise they made. Dully Klington and Parling realised that their adventure was at an end and their story would never reach the world.

But wait! Klington had an inspiration. "Parling," he sobbed almost incoherently, "turn the oxygen regulator throttle full on!"

No sooner had they done so when renewed life flowed through their veins. They felt rejuvenated, intoxicated. Once more they struggled onward, with the roar of the waters always present in their ears, like monstrous grasshoppers advancing inexorably.

The respite was brief, however; for a time it worked well, but the extra flow of the life-giving fluid used up their energy at an enormously increased rate, with the result that after a short interval of superhuman activity, they fell inert to the ground utterly exhausted. Nothing now could possible save them, it appeared. As they lay groaning in the oozing vegetation, waiting hopelessly for the end, they became once more conscious of that regular booming sound emerging from the bowels of the earth, which they had remarked before, but now at a greatly increased volume.

And now the mighty swirl of waters was upon them, and all wild speculations as to help from the originators of the mysterious beating were engulfed in the lashing fury of the wave. Up, up, it swept them right to the top of its lofty crest. Klington, feebly trying to float on the smoother upper surface, felt himself borne along irresistibly, whither? His torch was still firmly grasped in his hand, as the drowning man is supposed to clutch the straw, and the ray inadvertently fell upon Parling, a few feet away.

Klington could barely credit his senses. Surely the weird effect of the solitary gleam playing about in a sea of darkness, combined with the fatigue of his faculties, was deluding him. With an effort he swung the torch round until it again illuminated the figure of Parling. No, it was impossible, impossible! He was reminded of the days of his far-off childhood, when the old Bible tales of long ago were related to him.

For an amazing miracle was being enacted before his very eyes! Parling, who appeared quite as startled as himself, was actually—walking the waters. Klington's blood ran cold as he turned his attention to himself and realised that so far he had never yet been submerged. In fact he was merely lying on the surface as naturally as one lying on a couch. He stood up and began to walk towards Parling.

Imagine, if you may, the amazement of that incredible meeting! These two, who had never expected to see each other again in the flesh, bad once more been saved in a miraculous fashion!

THEY walked to each other, shook hands, and grinned in delighted astonishment! Then it was noticed that the water gave way a little under their feet, but that the surface was not even broken. It was as if a tight impenetrable skin was stretched over the entire seething liquid.

It was comparatively quiet up here, so far above the noisy tumult where the water came in contact with the ground, and conversation was unrestricted. The inklings of a great idea had come to Parling when first the wave swept him up in its embrace, and now he became wildly excited, whooped with joy, and slapped Klington on the shoulder so that he fell flat, for it was a difficult task to keep one's feet on the smooth skin-surface. "I have it!" I have it!" he cried, in tones suggestive of a man who has suddenly solved an almost insoluble problem.

"Have what?" enquired Klington, rather annoyed at his companion's unaccountable exuberance.

Parling calmed down somewhat, then said grandiloquently, "With all your philosophy, you have no doubt been unable to see the explanation of all the mysterious occurrences which we have recently undergone?"

Klington assented bewilderedly.

"Ah, Klington, it must be due to bad training in your youth! Your philosopher-masters have told you that everything is relative, and you believed them, but such is your mind that you are unable to apply it in even simple cases! Klington, it requires the mind of a mathematician to do that! My explanation, at once elementary and logical, embraces everything from the black forest to the flood which now carries us along! And if it is true, then it also indicates another danger ahead, far more terrible than the ones we have yet experienced—", and Parling stopped for a moment and peered into the gloom ahead.

Before he could say another word, before the astonished Klington could utter a single question, the surface of the water tilted and assumed an angle so steep that it was no longer possible to remain upright. Klington and Parling instantly were upset upon their backs and began glissading down to a fate that was, at least to Klington, unknown.

They had no time to remark upon this frightful contretemps; it was as much as they could do to keep their feet foremost. But extinction was not yet to be theirs. The waters swept round a gradual curve to the left, ever steepening, but the Terrestrials, since they were not actually immersed in the fluid, did not partake of its friction and hence careened on in a straight line, owing to their own inertia, in the direction of the tangent. They were crushed with staggering force against a rocky rough mass—the first elevated land they had encountered since leaving the albous mountains—jutting up out of the water to a considerable height.

With the energy born of despair they clung with all their weight to the slightest projections the island afforded, and Klington with great difficulty managed to haul himself upon a narrow ledge, in the process dropping his lamp, which was instantly swept away in the current.

Parling's torch, however, indicated the precarious position of his companion, who had obtained a grip on the ledge but could not pull himself up. Klington carefully made his way along the ledge, bent over and removed the torch from Parling's grasp, placed it in a cranny so that it shone upon Parling, and heaved him out.

A few feet further on the ledge abruptly terminated, so they were obliged to walk along it in the other direction. Not far, however, had they progressed when they were forced to stop. An impassable wall blocked the way, and they stood, helplessly flashing the torch around. Yet there was still a hope. The beam revealed no passage round the obstruction, but about twelve feet above their heads the ledge seemed to continue.

Klington, the lighter of the two, climbed upon Parling's shoulders and thus enabled him to reach the upper ledge. It was then an easy matter to help Parling up the rock-face. The new ledge sloped steeply upwards, and the slipperiness and narrowness of the path made it extremely difficult to walk. For an eternity they plodded onwards in silence, broken only by a disconcerting gurgling sound that became louder and louder as they mounted.

The path took a sharp turn to the left, following the contour of the island, and the travellers, weary and hungry, found themselves on a wide platform surrounded by rock on three sides and having blank space on the other. Klington and Parling shuddered with horror as a flash of the light revealed a ghastly pit of unestimable depth into which the waters plunged in the form of a vast whirlpool, originating the gurgling noise. But for the timely intervention of this island, they would now be lost in its depths.

"As I thought! Just as I thought!" said Parling, gazing into the abyss.

CHAPTER IV

An Explanation and a Tragedy

WHEN the Terrestrials had made themselves as comfortable as possible on the rockbound square and partaken of food, they slept for some six hours. Parling refused to say a word until he had rested. As for Klington, his mind was in a whirl at the anticipated explanation. Had Parling really the solution to all the peculiar phenomena which they had seen?—the lack of horizon, the sensitive black holes, the interlacing regular furrows, the unchanging illumination, the abrupt and orderly white mountains, the hideous denizens of the pass, the strange underground beating with its accompanying quake, the plain where everything was red, the falling rocks which never reached the ground, and lastly this turbulent sea sprung from nowhere?—or were the hints he had thrown out merely the gibberings of a maniac?

In the morning, or rather, when he awoke, he was agreeably surprised to find that the lamp was now unnecessary. The light, though faint, was good enough to enable him to perceive nearby objects. He aroused Parling, and after they had eaten he immediately enquired of that which he was intensely curious to know.

"It is really very simple," said Parling, "in fact, almost obvious, at least to a discerning intellect like mine!"

Klington was much too interested to parry, and Parling went on.

"The key to the mystery lies in this-we are not on a planet at all!"

An exclamation escaped from Klington. Parling rose up and stood on the edge, his back to the gulf, in his favorite attitude of emulation of the Rhodian Colossus. He was the triumphant man now.

"No," he said dramatically, "we are not upon a planet—but on the skin of a monstrous, Gargantuan animal! Is it not obvious? We landed on the lip of the beast, where sensitive stems no doubt were analogous to down in our world, and travelled down to one side of the lip. There was no horizon almost on every side because we were on the slope nearest the mouth, and the ground curved upwards all around until it was out of sight. You can understand that, at least.

"The mountains we encountered, Klington, were indubitably teeth! And I suppose the large swift-footed organisms we met there can be likened to the bacteria in our own teeth which cause decay if not removed by toothpaste. Well, we journeyed between two of the teeth of the monster, and thus entered its mouth. Time and space seem both to be greater in this universe than in ours, for the heartbeats we heard were quite slow.

"The similarity between the creature and humanity is so great that the interior of its-mouth is red, as we saw. The sea that swept us here is, of course, merely saliva, and the cracking sound we heard during the gale must have been some titbit the monster was crunching at the other end of its mouth! We shall soon see it."

"But how do you explain the miracle of walking on the waters?" interposed Klington excitedly.

"I don't quite understand that," said Parling slowly, as if unwilling to divulge any flaw in his theory.

They fell silent for a moment. Klington was reflecting deeply. Suddenly his face lit up. "I've got it!" he cried.

~ "Why, it's quite obvious, and is a strong corroboration of your idea."

It was now Parling's turn to be confused. "Indeed," he said.

"Yes," said Klington, "it was due to surface tension! Have you ever seen a microphotograph of a fly crawling on the surface of a stream? The surface tension, common to all fluids, gives the appearance of a tight elastic skin stretched over the water,—just the effect we observed. Compared to this Brobdingnagian animal, we were much less than any insect. The phenomenon is not due, of course, to the large volume of liquid present—or else no boat on an ocean could ever sink on our earth—but to the fact that the molecules themselves composing the saliva are correspondingly bigger than earthly molecules."

PARLING was pleased at this support of his theory.

"The philosopher's mind," he said, ‘scan lead on to fresh facts, once the mathematician has shown the way.

' "The apparently ‘falling rocks' which caused us to depart in such a hurry, as I suppose you have guessed by now, were none other than the upper set of teeth of the monster."

Parling turned around and pointed to the tremendous hole below him.

"And this, Klington, is undoubtedly the creature's throat! Think of it, man, think of it! It must be at least five hundred miles deep!"

Then swift and sure, on the heels of this statement, came death. The island which had stood them in such good stead, gave a sudden spasmodic twitch as if revolting at the thought of these presumptuous and daring mortals from another world. With a terrible despairing cry, Parling, who had been standing on the very edge, toppled over, hands madly clutching at empty space, and vanished into the boiling maelstrom!

Klington was flung against the hard sidewall and knocked unconscious by the shock. When his senses revived, the light was as bright as day. No doubt the monster was. again opening its mouth. For several minutes he lay dully, while slow realisation came to him of the loss of his companion and of the fact that he was now absolutely alone in a strange world, aye, imprisoned in the jaws of a nightmare animal!

How long he remained there he had no means of telling, for his watch had stopped at the impact. Many times the island was shaken by spasms, but none so violent as the first. He kept as near to the inner wall as possible, in fear of sharing the fate of the unfortunate Parling. Then came the dread moment when he fitted the last oxygen cylinder to the breathing tube, and still the waters had not subsided. He remembered Parling's haversack, which lay where Parling had had his last sleep. To his joy it contained a plentiful supply of the essential cylinders. At that instant the roaring of the waters ceased, and he went to the brink and looked over. The whirlpool was now reduced to a mere trickle. It was necessary to go at once before a second deluge appeared.

Klington fastened his haversack, replenishing his diminished supplies with those of Parling, and, climbing down the narrow ledge, jumped up to the floor of the mouth. He had gone but half a mile up the slope towards the white barrier far away in the distance when a fresh surprise greeted him. The ground curved upwards much steeper than he had observed it before to a height of several miles, and ran flat for a time until it encountered the tops of the white mountains!

He could not imagine what had occurred for a considerable period, then it came to him in a flash. The monster had merely raised its tongue, the tip of which was now resting on its teeth!

It was no good climbing to the top of the teeth, so he made a detour to the left, in which direction he thought lay the nearest edge of the tongue.

After a journey of many miles, he came at last to the edge, clambered down the rough side, and stood upon the mouth-floor proper. He continued along the five-mile wide channel between the cheek and the tongue until he came to the teeth. The short journey over, in the pass between two of them, where he encountered the ‘usual microbe-like creatures, he stood on the clear plain which alone separated him from the vicinity of the one link with the earth.

Klington raised a powerful pair of prismatic binoculars lo his eyes, and scanned the forest of black stems for the white sheet which indicated the position of the ladder. Imagine his horror and dismay when it was nowhere to be seen! For half an hour he searched, while a cold tightening grip at his heart made itself more and more felt.

Then to his great surprise his attention was attracted upwards. With an unpleasant jolt he perceived that some chance movement of the beast which bore him had caused the ladder to ascend to a height of four or five miles. It was also much nearer thaulbefore; he could even make out the end of the rod beside the rope ladder‘ and the sheet. What a terrible predicament he was in! Hope seemed lost as he gazed with hungry eyes at the precious connection to his world.

Desperate Moments

IT was moving so quickly that he could just perceive its motion. It was almost half way between its former site and the nearest tooth. A faint hope surged in his breast. It was his only chance for life, for soon the last of the oxygen would be utilized. If the motion continued in that direction, the ladder would shortly be close to the peak of the tooth. Instantly, for no time was to be, lost, he flung away much of his provisions, and all the leaden weights, retaining however the remaining cylinders, and returned through the gap in huge hops.

Without a pause he trekked alongside the tongue until it was near enough to the ground to make the ascent practicable. Without daring to delay for meals on he climbed up the steep difficult slope of the lower portion of the tongue, until he arrived at the flatter upper portion. Here going was much facilitated, but he did not relax his efforts, and by exercising his willpower to the utmost, he forced his tired limbs toward the tip of the tongue.

While down in the pass below, he had noted the tooth towards which the ladder was moving, and counted how many teeth lay between it and the end of the row. With this to guide him, he hurried on, hunger now added to the fatigue.

Within five hundred yards of the tip, he paused and flung himself prostrate with a cry of despair. The tongue had been slowly contracting and arching upwards and now the tip was a good eight hundred yards from the opposite peak! As if in mockery, there dangled the ladder above the tooth, just within reach of a vertical jump! By the time the ladder passed over the tongue, it would be too high!

Klington stood up with sudden firm resolve. There was but one thing to do. Casting away his haversack he ran to the very tip and flung himself bodily through the air in a mighty attempt to span the gap.

The feat was by no means impossible, but there was a large element of risk for a man in Klington's weakened state, despite the slight gravity. Up, up he rose to the top of the parabola and then began to fall with a slow acceleration. His mind reeled at the thought of the terrible gulf of twelve miles which lay below him, but he determined not to look downward.

Presently his heart froze with horror as he realized that he could never attain the opposite side. His weary limbs had failed him at the last! He would fall short by about three yards! A small distance, true, but as good as infinity in his present condition.

He had but two or three seconds in which to consider the position before he passed below the level of the opposing brink. His subconscious mind, or "subliminal ego", unknown to himself, was working with lightning rapidity.

"Suddenly there flashed into his conscious mind two facts which he had learned when a schoolboy. Projectiles have the maximum range when they leave the mouth of the gun at an angle of forty-five degrees to the horizontal," was the first, and the second was the principal of the Goddard rocket—reaction.

The heaviest object he had which could be detached in a moment was the single remaining oxygen cylinder—heavy because it was nearly full of liquid oxygen. Hastily he unfastened it and flung it with all his strength at forty-five degrees downwards, away from the crest of the tooth. The impetus was not great, for his mass was much more than that of the cylinder, but owing again to the slight gravity, it was enough.

Klington's straining fingers were brought just within reach of the edge, and he swung himself on to the flat surface.

Staggering to his feet, he looked round for the ladder, and jumped. The lack of oxygen was already telling. He swayed. The body cannot remain alive for more than three minutes without oxygen, and his lungs were clamouring for the fluid. He gathered himself together and leaped again, with a growing oppression upon his chest.

His hand just grasped the lowest rung!

He was saved!

With-slow, weary steps, gasping for breath, Klington painfully dragged his body up the ladder, and ascended into the kindly world of men.

THE END