Help via Ko-Fi

CHAPTER I

FLIGHT

ALWAYS the drums talked in the distance, ceasing neither by night nor day. He had lost track of time. He knew only that open country lay somewhere to the south. Toward it he drove himself by instinct, draining himself of last reserves of energy that should long ago have been exhausted. He ?ed from the drums and their prophecy of doom, but always they throbbed with a monotonous and maddening beat.

His face was haggard. A wild light shone in his deep-sunken eyes. Beard matted his cheeks, and his hair straggled unkempt. In his blind flight the jungle had tattered his clothing. His sun-baked skin bore the scratches of thorns and the weals of insect bite. Fever consumed him, but not even delirium could end the fear that forced him on to protect the treasure he carried.

He plunged through green nightmare. Only twilight filtered down from the roof of trees and creepers, the tangle of foliage and branches. The vegetation dripped moisture. His feet squashed sodden, decaying matter. The air steamed like a hothouse, with a wet and musty smell.

Amid the half-light, an evil beauty flourished upon death. Immense orchids, black as ebony or blood-scarlet, striped with golden green, purple, or waxy white, reared their fantastically gorgeous blossoms out of slime and rotting mold. Macaws squawked harshly. Hummingbirds and tanagers made streaks of brilliant color. There were mushrooms two feet tall, and mottled with scabrous pink. Malaria mosquitoes and carrion flies droned, while now and then the savage scream of a mandril silenced the monkeys.

Crocodiles chased him when he splashed through a murky pool of the stream he was following. Later he floundered across a swamp, waist-deep in ooze. The slime-covered surface rippled. He felt the touch of soft and horrible things that wriggled.

No sane man could have survived so frightful a passage. He should have died a hundred deaths. He should have left his flesh and bones to rot with all that other decaying matter. He reeled onward.

He passed ancient ruins, engulfed by the tide of vegetation, but still preserving a basic outline. Upon colossal blocks of fallen masonry were incised symbols of a language unknown. He had heard legends of lost cities such as this, but he did not stop to investigate. He clambered across mounds and slippery walls.

And always the drums talked, throbbing afar, surrounding him with doom. The heavy revolver lay ever ready in his hand. He expected each moment to feel a poisoned dart or a spear, to meet a ring of painted and grotesquely masked faces. He saw no one.

A tangible foe would have ended the persistent torture of his nerves. His was the terror of expectancy, of inevitable death postponed from minute to minute. He must keep going, keep going, with the stolen witch-charm his prize if he won out. He stumbled on blindly.

CHAPTER II

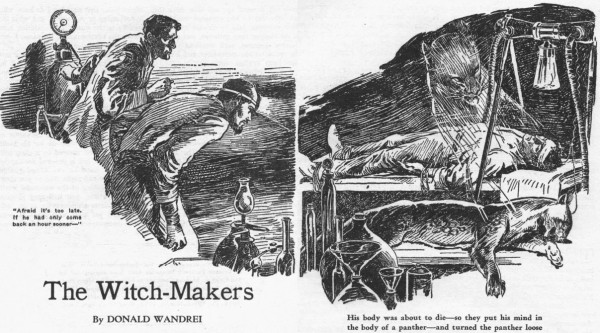

THE WITCH-MAKERS

TWO white men looked down at the cot where the unconscious figure lay bandaged. The younger man, of square build and overweight for his five feet nine, asked in a deep, quiet voice, "What are his chances, Burt?"

"He hasn't any. Oh, the proverbial one in a million at the outside," the older man answered in a dry, rather testy tone. Dr. Ezra L. Burton was a spare and bony scarecrow, his semi-bald head fringed with sandy hair. What was visible of his features looked ruddy, but mostly they were concealed by a black beard of full and alarming proportions. He added, "It's a miracle that the duffer ever got out of the jungle. I've done what I could, but he's dying.

"Travers, I sometimes think that medical science, so-called, is a brutal farce. What was the use of patching him up today so that he can die tomorrow? He's going to die. He should have died days ago, but some silly will to live kept him going until he stumbled into our camp. It would have been better for him if he died in delirium. Now he'll wake up just long enough to know he's dying and to hate himself for it and to hate us for giving him a lease on life just long enough to know he's through."

Travers filled a briar pipe and lighted it.

"There's nothing to identify him except his initials." Burton poked a blunt and gnarled forefinger among the collection removed from the strange's pockets. It included a bandana, cheap watch, magnifying glass, some coins and gold nuggets, pocket knife, cartridge belt, matches, and the .45, with the initials "L. A." carved on its butt. Amid these items lay a remarkable figurine about six or seven inches tall.

A little less than three inches of it represented a misshapen torso and spindly arms and legs of solid gold. The rest was an enormous emerald for its head. Of rectangular shape, it had been beveled to portray a two-faced monster of inhuman and unearthly attributes, suggesting abysmal antiquity, beyond history. The edges of the jewel had rounded from the wear of countless generations of hands.

Burton lifted the weird figurine. "He would seem to have been an itinerant trader. This idol probably is the key to the mystery. It looks like a fetish, some witch doctor's symbol of power or some tribe's emerald god. I suppose the chap stole it. It isn't exactly the kind of thing you expect stray visitors to carry around with them. As to who he is, my guess would be Leif Abbot, but it's only a guess."

"Leif Abbot?"

"I know of him by hearsay. A Yankee trader with a flair for digging into hidden places. In other words, a complete fool or trail blazer, depending on your point of view. Born in the Mid-west, Minnesota or Wisconsin, as I recall, went to Africa a few years ago, fooled colonial officials, tricked the natives, played both ends against the middle, and became a sort of legend. An imaginative cuss with a heart of gold—fool's gold."

Travers asked, "I wonder if he had anything to do with the drums we heard a while back?"

"I meant to find out about them. I'll see what that black thief Mokoalli has to say."

After Burton stalked out of the tent, Travers dropped into a folding chair.

Growls, snarls, and chattering made an uproar outside the tent. It was always thus at nightfall when the jungle creatures could be heard afar, and the captured animals grew restless. Within the camp enclosure, rows of cages held specimens of the district's life. Lion, jackal, ape, and zebra; python and mamba; buzzard, ostrich, even eels and brightly striped fishes lurked in the tanks and cages.

Travers glanced at the stranger, who was breathing heavily with a rattle in his throat.

IN the same tent, looking oddly out of place, stood modern scientific materials of obscure and specialized purpose. A metal operating table rested beside a curious device that had been assembled from numerous parts. These included a small dynamo, some queerly shaped glass tubes and ovaloids reminiscent of X-ray apparatus, and two tiny plates with a mass of wires hanging from each like fine, golden hair.

Travers reached out and picked up the grotesque idol. He hefted it reflectively, fascinated by its eyes in different colors, and the way glimmers of green flame welled from the heart of the great emerald. There might be fifty or a hundred dollars' worth of gold in the idol, but the jewel must be worth a thousand times as much, and the entire object even more as a curio or museum piece.

He continued to inspect the gem when Burton strode in, his black beard waving, while beads of sweat glistened on his ruddy forehead. "Mokoalli is a liar as well as a thief," Burton announced in the tone of a weather report. "He stole one of my best scalpels which I said he could keep if he told me the truth, whereupon he gave me nothing but the most outrageous lies. He said the drums were talking not because the jungle tribes were tracking the fugitive down, but to warn other tribes to keep out of his way! They thought he was bad medicine, driven by devils, and though he'd made off with a powerful charm they were afraid to touch him till the devils consumed him. They were just keeping an eye on him. That's Mokoalli's story. Moko is a liar. I took the scalpel back."

Travers removed the pipe from his mouth. "Did it occur to you that he might have been telling the truth?"

Burton looked surprised. "Why, no, it didn't."

"I think he earned the scalpel."

"He'll steal it again soon enough."

"The savage mind works in queer ways. The emerald that means a fortune to us wouldn't mean a thing to them except as a fetish or idol. If they were afraid of Abbot, they might well have waited until he died before reclaiming the charm. They might even have expected the emerald god to take vengeance and kill him. Then, when he stumbled toward our camp, the drums stopped."

"That's what Moko said. The natives seem to be pretty much afraid of us by now."

"Do you blame them?" Travers, with a glance at the fugitive, suggested, "Let's break camp as soon as he comes around or passes on. We've got our data. There isn't much more we could accomplish here. Our work's done. Another three months of this and I'll be ?t for the booby hatch. Besides, the war zone seems to be creeping up on us. I've seen airplanes in the east twice in the past week. One of these days a bomber may pick us out for target practice or some fancy ground strafing."

Burton tugged at his beard reflectively. He felt the pulse of the patient, listened to his heartbeat, and took his temperature in the course of a careful examination. He shrugged as he turned away. "He's done for. A day or two at most. Even if he recovers consciousness, which is problematical, he's too far gone for recovery. We'll break camp as soon as possible."

"Good."

"But," added Burton with a new note of decision in his voice, "we will immortalize him by using him as our first human control."

Travers frowned. "Why? If he's on the way out? What good would it do?"

"It's his body that's broken down. If he regains consciousness, his mind and intelligence should be relatively unimpaired. It's only his life force, his vital spark, the unit of identity that is his mentality which we need. And we may be able to prolong his life somewhat. In any case, here is an outside chance to obtain data of immense, I might say priceless importance.

"As you say, we've successfully finished our work with the animal controls. The ape-jackal interchange simply corroborated earlier findings. There is nothing more to be learned by duplicating previous experiments. We need a human control. Our next step must involve a human control if we are to open up vast new fields for research.

BURTON'S accents had taken an introspective tone as though he expressed aloud a passionate inner conviction that drove him. "Thus far, we have only objective data. The lower vertebrates couldn't tell us their reactions and experiences in a new environment. Only man can do that for us. We've already made revolutionary discoveries, but we stand on the threshold of a greater miracle than anything we've yet seen or done.

"We interchanged the lives of a monkey and a fox. Do you remember how elated we were with the success of that first experiment? How we watched the fox in the. monkey's body cling to the ground? How the monkey in the fox's body vainly tried to swing through the tree tops? We put the personality of a rhinoceros into the body of a zebra, and that gentle animal became a driving, tearing Juggernaut of death, while the great rhino inhabited by the zebra's spirit ?ed in fear from the lion it could have crushed.

"For weeks and months, Travers, we've torn spirit and flesh asunder. Here in fifty square miles that contain almost every kind of the climate and life of Africa, we've learned more about animal behavior during our three months than all mankind learned in three thousand years. We've stolen a march on evolution. We've knocked the natural selection of species into a cocked hat.

"Why can't we do the same with the spirit of man? Maybe we can't, but we won't know till we've tried. And if we try and succeed, would you even attempt to estimate how much we'll enrich man's imagination and add to his knowledge? Think of what it would mean if we enabled man to look at the world through the eyes of his pets, a dog, or a cat, or a horse! Wouldn't he have a more tender feeling toward them and a more profound appreciation of his own capacities? Isn't it possible that, in course of time, his pets would acquire a new intelligence of the order of humanity? Isn't it conceivable that they could then be trained to speak, with results in strange, unimaginable new friendships?

"And after that, Travers—after that— the transference of intelligence from one man to another! It's a magnificent and terrifying thought, isn't it? If we made it possible, where would it end? In greater peace for mankind? Would he understand his fellow men better and comprehend more fully their weaknesses and follies, their dreams and nobilities? Would he spy upon his friends and try to benefit by what he learned? Would each man cease to be an individual as he gradually absorbed the characteristics and peculiarities of other men? Or would he become more rapacious than ever before, carried away by the thirst for knowledge, made drunk by the infinite capacity for unlimited power?

"I can't answer my own questions, Travers. They're beyond answer except in the fateful mold of experience. But we have it within our hands to take the first deliberate step, the step upon which all else hinges. We'll be tampering with the mysteries of life, yes, but it's life that's hopelessly doomed anyway. Abbot, if he is Abbot, can die unconscious and forgotten, or he can have experiences never dreamed of in his last hours. He can die with the certainty of a posthumous immortality that will never fade until earth itself runs its course or man perishes in the eons of the far future."

"You might at least wait till he comes to. He ought to have his say about whether he wants to be a guinea-pig. And there's the little matter of the emerald." Burton shook his head decisively. His beard jerked like an erratic pendulum. "The emerald? We can donate it to a museum. He won't recover, and as for the experiment, perhaps he would object, if he could. I don't suppose he'll thank us for extending his life under altered circumstances. That is too much to expect. And he's apt to suffer a severe shock when and if he awakens, but he'll recover more quickly and adjust himself better than if he approached the experiment with all the fears his imagination could provide."

"Suppose the one chance in a million pulls him through? What if he survives? He could make it pretty hot for us. Society might not approve of our methods or our goals."

"That's why we're here instead of in a nice comfortable laboratory at home. If all experiments were subject to the whims and censorship of society, civilization would still be in the Dark Ages."

"That won't be answer enough if he survives."

"We'll find answers when the need arises. And while I stand here arguing with you, his hold on life grows thinner, and if we don't act immediately our great opportunity will be gone."

Burton walked over to the dynamo and started it. A low hum like the buzz of a persistent mosquito filled the tent. What looked like mist in one of the oddly shaped tubes glowed with a milky light. The mist became rapidly less opaque until only a softly shimmering radiance remained.

He slipped a metal band around his head. The band had a small bulb and reflector in front. He pressed the switch. A beam of light leaped out. He removed the unconscious man from the cot to the operating table, arranged a number of surgical tools, and pulled rubber gloves over his hands.

Then he left the tent. A few minutes after his return Mokoalli and another native, panting and grunting, brought a cage in. The beast in the cage snarled sullenly.

As the patter of footsteps receded, Burton with a dextrous motion plunged a hypodermic through the bars of the cage. The beast roared and lunged viciously at his arm.

"He almost got you that time," said Travers in a voice of regret.

The guide-light focused on the stranger's head. Burton took a pair of scissors and snipped the hair off the base of his skull.

One by one, the surgical implements grew red. The sound of a man's breathing became harsher, and magnified in the stillness. The air became uncomfortably hot.

The moon rose, and weird noises drifted from the jungle. The animals yowled in their cages. Within the tent, the dynamo droned like a relentless carion fly.

CHAPTER III

STRANGE AWAKENING

LEIF ABBOT passed from one fantastic dream to another. In some he was a boy on the Midwestern prairies, chased by monsters foreign to all the continents. In others he wandered endlessly through forests and jungles, alone and hopelessly lost, or accompanied by dead friends and pursued by invisible terrors. There were periods of blankness and periods of skyrocketing flashes. At times he was almost on the verge of knowing that he dreamed, but then he slipped away again into the phantasmagoria of unconsciousness.

Pain entered his dreams. He was running, running, running, with leaden steps that took him forward more slowly than the progress of tortoises. Balanced upon his head was a great cube of gold that for some reason he could neither touch nor dislodge. He was compelled to stagger onward with that intolerable weight while his shadowy pursuers drew nearer with the speed of hawks. Knives flying in all directions impaled him.

Then the nightmare lay behind him. His head throbbed. He felt stifled and breathed unevenly, but he knew that the dream had ended. He lay still, his eyes closed as he' half-remembered his last hours of consciousness. Buala, the witch doctor—the emerald god that bad passed from tribe to tribe and from father to son through untold ages until it fell into Buala's custody—his days of haggling and cajoling, with Buala adamant in his superstitious faith in the emerald god's magic powers.

Leif Abbot had wanted that treasure. When he couldn't get it by more or less legitimate -means, he took it by theft. In spite of his African adventures, however, he had underestimated the emerald's influence and prestige. He awoke one night to find his own carriers attacking him, and to hear the throb of drums. He escaped with the jewel, but his porters and guides deserted him, taking all his supplies.

He could have followed the river, which would have taken him downstream through hostile villages that he now could not pass through and live. He chose the southward course toward the headwaters and open country, where he had heard rumors about two white men whom the natives called "Witch-Makers." Then came the nightmare of his flight through the green hell, the insect hordes, fever, thirst, hunger, and finally delirium. He remembered nothing from that point on.

His thoughts growing clearer each moment, he opened his eyes. A roof lay curiously near, scarcely a yard above his head. He was lying on his side on the floor. Bars interfered with his vision, but he saw two white men in the interior of the tent, and—lying upon an operating table, his own body!

Leif Abbot closed his eyes in a daze. He must be dead or in the grip of delirium still. An odd panic filled him, a premonition.

He forced his eyes open again and stared at the figure on the table. He was unquestionably looking at his own emaciated, fever-ridden body, with a metallic gleam showing through bandages on its head!

Suddenly afraid, he strove to rise. Unable to balance on his legs, he toppled crazily and fell with a jarring thud. His head throbbed. A moan of pain came from his lips—but to his ears it sounded like the whimper of an animal!

The room reeled around in his vision as he fell. His head lowered, and his stunned gaze fastened upon the padded paws of a beast, and black-furred legs. They seemed part of him. He stretched out a hand, and stared in the hypnotism of horror as a paw scraped the floor where his hand should have been.

FOR a timeless drag of eternity he lay immobile, trying to figure some meaning out of the strange distortion of things. He was not dead, because he was not disembodied, yet he stood apart from his rightful body which lay beyond» the bars. The cage inclosed a beast; and he was the beast.

As his thoughts skittered through this new, waking nightmare he became conscious of a voice. It sounded extraordinarily loud and shrill, like a thunderclap. He realized vaguely that he had difficulty understanding the words, and that the room was filled with a multitude of familiar sounds magnified in volume, while other sounds of which he had never before been aware assailed his hearing. His ears had acquired a preternatural sensitivity. In the amplified breathing of the speaker he heard the lungs expand and contract, the heart beat. He heard a fly crawl on the canvas of the tent. When the second man tilted his pipe, he heard fingers rasp on the bowl, and a rustle as of raindrops when some ashes fell to the floor.

"Leif Abbot, if you are Leif Abbot, can you hear me?" asked the booming voice.

The beast in the cage scrambled to all fours and swayed against the bars. Glaring sullenly out, he lowered and raised his head.

Before the speaker could continue, there came a wild interruption. Leif Abbot, looking through the bars, saw his body stiffen on the operating table. The eyes opened with an expression of animal ferocity. Ropes bound the body, but it burst the ropes with a surge of strength that Leif Abbot in all his life had not equaled.

The mouth parted, but from that human throat came a snarl born of the jungle. The body hurtled across the tent in the spring of an animal, teeth bared, arms outstretched like paws ready to rip and gouge. The white men scattered and for seconds a furious battle raged. The white men won, but only because Leif Abbot's body was too exhausted to endure the terrific strain put upon it by the untamed spirit within.

When the struggle ended, the body lay motionless under the influence of an opiate. The taller of the men, the one with the waving black beard, painted their scratches and wounds with iodine.

After he had finished, he turned again toward the cage. "I am Dr. Burton. My colleague is Dr. Travers, a physicist and biochemist. We have been engaged in experiments here for several months. When you staggered half dead into our camp, we were compelled to adopt extreme measures or you would already be dead.

"Do not be alarmed. Whatever seems incredible to you is really very simple. We have discovered how to separate the life-stream or consciousness or whatever you want to call it from the body to which it belongs, and to effect an exchange with some other body. Thus far we have worked only with the lower vertebrates. In your case, your chances for survival as Leif Abbot were so small that we operated upon the six layers of your cerebral cortex and transferred your identity to the body of a strong and healthy black panther. The panther's identity now occupies your own sick and weakened body. By this interchange we hope to strengthen your body sufficiently so that your identity can later be restored to it, with better chances for your recovery and survival.

"In the meantime the door to your cage is open behind you. Go into the jungle, if you like. You probably will be better off there. You have all the intelligence of man, and all the senses and instincts of the big cats. You should be able to avoid any danger and survive any attack."

Leif Abbot attempted to answer, but only a rumbling growl issued from his throat. His new vocal cords either were not capable of speech or would require long practice.

The greenish yellow eyes of the panther glowered his mute hatred. Burton's glib explanation failed to satisfy him. Not for an instant did he believe Blackbeard and his companion. They wanted the emerald god for which he had risked his life. What poorly paid scientist would pass up such an opportunity for easy wealth? They didn't have courage enough to let him die or to kill him. But it would be murder just the same, in a different form, more protracted, and under the guise of science.

Neither Burton nor Travers spoke again They watched him in silence; and he in turn glared balefully from them to the emerald that still lay among his effects, its glitter matched by the smoldering flame in his eyes.

Turbulent emotions swept him. Hatred rankled at the back of his thoughts. He tried to adjust himself to his weird change of state. He plotted a dozen ways of tricking them in order to regain possession of his treasure, but he hopelessly confused his lost resources as man and his as yet unknown abilities as panther. Forgetting his new form momentarily, he tried to grasp the bars of the cage, but his paws merely slid along the bars. He had no fingers to help him now. He had never before appreciated so fully the infinite utility of hands.

Probably they were merely awaiting his departure into the jungle before killing the panther-spirit that now occupied his real body. And there was absolutely nothing he could do for the present, except take their advice before they changed their minds. He might be doomed to die in the jungle, but while he lived he could scheme ways of vengeance.

He stared for the last time at his captors, then turned and bounded into the darkness outside.

CHAPTER IV

THE BLACK MARAUDER

THE rest of the night, all the next day, and the following night the black panther remained away. Burton and Travers watched the body of Leif Abbot, which seemed to grow stronger under the drive of the fierce animal spirit that now dwelt within it.

Toward dawn of the second day, Burton awakened from a fitful sleep to hear a weight dragging on the ground. He sprang up and flashed a light on it. The panther, its right hind leg broken, and bleeding from numerous wounds, dragged itself forward. It did not whimper. Its glazing eyes still burned with sultry hatred and rebellion though death fast approached.

"Travers, quick!" Burton shouted. "Turn on the psychotransferometer! Get out adrenalin! Scopolamin!"

He leaped to the dying panther and gathered it in his arms. Its savage heart beat heavily. He carried it to the operating table and laid it beside the shackled body of Leif Abbot.

The hum of the dynamo had already begun. Pale, vaporous light shone in the vacuum tube. Burton fastened the silver plate in the panther's skull and the similar plate in Abbot's cranium to wires connected with the transference apparatus.

It was not a torrid night, but sweat glistened on his face. He watched anxiously, tugging at his beard.

Travers shook his head in doubt. "Afraid it's too late. If he'd only come back an hour sooner—"

As though in mockery at his words, the gleam of animal ferocity suddenly returned to the panther's eyes. For a moment it snarled at them and made an effort to attack. It shuddered, while its eyes filmed more swiftly. The brute thirst faded from the eyes of Leif Abbot as his human identity reentered his body. A gleam of sanity and intelligence lingered for seconds, gradually to be replaced by an expression of trance-like repose and suspended willpower when the drugs took effect.

Burton heaved a deep sigh. "A close call, that. A few minutes more and our trouble would have gone for nothing. Too bad the panther died, but we have all the notes we need on its behavior while it occupied Leif Abbot's body. And now let's see if he can or will tell us what he did in the part of a black panther."

He bent over and looked into the subject's eyes. They were wide open, but the hypnotic blankness had grown complete.

"Leif Abbot, can you hear me?"

The lips hardly moved, to give a faint answer, "Yes."

"Last night in the body of a panther you left us. You have been gone for two nights and a day. Where did you go? What did you do? What happened to you after you left? How did you receive the wounds?"

SPEAKING as though from a distance, his unblinking eyes exhibiting no change of expression, Leif Abbot said, "When I crept out of the boma, the moon rode high. It was a red moon. It bathed the plain in blood. Black shadows and scarlet moonlight, all the world was strange. I have never seen so strange a world. It was like the landscape of another planet.

"I heard sounds beyond the range of my normal ears, the wings of night birds, the gliding of a snake, an indescribable chorus of separate sounds around me and drifting from the distant jungle. I heard grass rustle in the faintest of winds. I saw colors that no man has ever watched. They are beyond the spectrum of his eyes, but my panther eyes saw them. I can't tell what they were like, any more than you could describe color to somebody blind from birth. You would have to see those eerie colors for yourselves.

"All my senses were immensely keener. I detected smells of hundreds of different plants, flowers, animals, insects, decaying matter, and other things, where before I had noticed only a sort of general-dank mustiness in the air. I was queerly mixed up. As a panther I noticed all these impressions for what they were. As a man I couldn't identify more than a part of them. I had half-memories that didn't quite bridge the gap between my own knowledge and the panther's instincts and habits. Certain odors made me afraid. The panther knew that they came from poisonous plants.

"I didn't know what to do, at first. For a while I strode around, accustoming myself to going on all fours, and to the movements of unfamiliar muscles. Gradually I got a feeling of power, for there was the strength of several men in that long, sleek, and ripplingly muscled body. I tried crouching and leaping, and found that pounces of twenty feet and more came effortlessly.

"I traveled northward, downhill, toward the jungle. I had some vague idea of hunting for Buala and taking vengeance on his tribe. It was a crazy idea because if any vengeance was to be taken it really belonged to him. At the edge of the jungle I stopped. I could see into it better than I could in the daytime with human vision. It was filled with a kind of grayish green light, more ghostly than twilight; the shadows were blackly green; and the patches of moonlight a sort of ghastly red.

"Maybe that's the way the jungle always looks to the great cats by night. I don't know. That's the way it looked to me and it gave me the creeps. My fears as man carried over into my life as panther. I shied at going into that monstrous tangle.

"Besides, I had an inner pull to travel eastward. I couldn't account for it, unless some latent instinct of the panther was asserting itself. Finally I began to ramble toward the east, keeping at the fringe of the jungle in a long, gliding run that I found easy to maintain.

"I put hours and miles behind me. I followed the instinct that urged me on. While doing so, I became more confident in myself and more sure of my pantherine body.

"Loping through broken, hilly country that was beginning to show a sharp upward rise some hours later, I felt a pull toward the northeast. I turned from my course into the hills and went back to the tangle. I found a dim spoor that lured me on. My surroundings looked as if they ought to be familiar. I almost remembered, but not quite.

"There came a turn in the faint trail I followed. I reached the base of a cluster of rocks. With no intention on my part, a kind of spitting growl broke from my throat. It was instantly answered by a yowl. From a black and cavernous opening that I now noticed, a panther emerged, a female, with a couple of cubs at her heels. I stopped in my tracks.

"For just an instant the creature was on the verge of greeting me home, and I knew that instinct had brought me to the mate of the black panther whose body I had taken possession of. She was deceived only for moments. By whatever subtle or primitive sense, she knew that I was an alien presence, a menace. She came through the air, a snarling fury, with claws raking in an attack that caught me by surprise.

"I suppose I could have put up a battle royal. I didn't. I don't know why. Probably some atavistic feeling of chivalry that was a hangover from my previous life made me turn tail and flee, as if all the devils in hell were yapping at my heels. That female cat was a demon if ever there was one. She ripped a shoulder wide open and took a chunk out of my neck before I got away. Those cursed cubs tumbled around and yowled in glee. I wish I'd knocked the whole litter into kingdom come.

"The sky was turning lighter. I left the denser thickets and ran toward higher ground.

"After that, I decided to go very easy about trusting instincts. I sniffed the air and got wind of a water hole.

"There I drank greedily and shook myself in the tepid water. It soothed the wounds I couldn't reach. There was a rocky ledge beside a trail that animals used in reaching the water hole. I bounded on top of it and lay down to await sun-rise.

"While I rested, a deer came mincing along the trail. It was a beautiful creature, a doe. I watched it drink and admired its graceful motions as it frisked away toward the grazing country to the south; and when it was gone I found that I was ravenously hungry and that I had blithely let my dinner skip off.

"My human scruples did not mean a thing in this case. A panther's body supported me and I had to support it in the manner to which it was accustomed. I waited a half hour before I spotted a wild boar. I made short work of it. Eating meat still on the hoof didn't exactly appeal to me, but my substitute palate gorged itself.

"I felt drowsy then. I turned toward the fringe of the jungle in search of a safe nook for a nap. I was looking for a high ledge or a cave, but didn't find anything with suitable protection. I scouted farther away from the water hole, trekking toward thicker jungle. As I was prowling along the trail, a sudden crackle gave me warning, but not warning enough. The ground opened beneath me. I made a vain scramble but felt myself falling. When I hit bottom, the wind was knocked out of me.

CHAPTER V

THE PANTHER STRIKES

"THOUGH I didn't fall a great distance, I landed on my neck and shoulders with stunning force. I lay there for perhaps a minute before I grew conscious of a pain in my right hind leg. I tried to get up. It was torture beyond me. I squirmed around, and in the dim light saw that the bottom of the pit held fire-hardened stakes imbedded point up. One of these had pierced the leg. It was only pure luck that others hadn't impaled me. I had fallen into an animal trap.

"A quick, careful jerk of the leg brought agony and freedom. I licked the wound. Looking around then, I estimated my chances of leaping from the pit at exactly zero. The stakes had been cleverly placed and the pit so constructed as to make it impossible for any beast to escape. Yet I escaped.

"How? It was absurdly simple for a creature who could think. I took a stake between my teeth and pulled it out. I turned the sharp point toward the earth wall and pushed it as far in as I could with my jaws. Holding the blunt end in my jaws, and pushing at the same time with two paws grasping the stake, I imbedded it for half its length.

"I removed another stake and drove it in beside the first. I continued the process until I had formed a ladder of stakes in pairs as high as I could reach. It took time, and every second I was desperately afraid that the hunters would come for the kill before I got out.

"My wounded leg hurt badly. I fell several times trying to climb the stakes, but on the fourth try I eased my weight onto the top pair. Then I rose in a swift half-turn on my hind legs. The stakes gave, but I had my forelegs over the edge of the pit and pulled myself out with my hind legs shoving and digging into the wall. The pain was intolerable. After I had regained freedom, I rested for several minutes, my ears listening for footsteps. I would have killed any human being that came in sight, if I could. My rage wore off, and I forgot the wound temporarily, when I thought of a sardonic jest.

"I went to work with a will and a vengeance. Ten minutes later I was crouching on the limb of a tree, hidden by foliage, and with the pit barely visible. The jungle steadily grew hotter as the sun mounted higher.

"I was feeling drowsy again when my ears pricked to the sounds of a party approaching. There were seven of them. I watched intently until the first, a strapping young buck with chest and cheeks cicatrised, came into view carrying a long lance. The only other thing he wore besides a loin cloth was a crude bracelet of some sort twisted tightly around his left arm almost at the shoulder. I don't know what it signified or why he wore it there. I noticed it because his left arm flashed up in a signal and he let out a yell you could have heard a mile off.

"The six others gathered around him, all jabbering at once, and all getting more pop-eyed by the second. I chose that instant to do the best I could on a loud laugh, Even to me the result was weird. They fled like so many rabbits.

"They looked scared silly. My jest had been a complete success. I had scraped a patch of ground smooth. Upon it, using my paw as a pen, I had scrawled, 'Yours Truly, The King of the Panthers,' and under the signature I had drawn the rough outline of a panther's head.

"The natives probably couldn't have read anything in any language, but they knew what writing was. They recognized the panther's head. They saw that there were no human tracks in the vicinity except their own. They saw how the panther had escaped from the trap. For the rest of their lives they'll be talking about the panther god or devil that left his signature.

"I drew back to a crotch in the tree and dozed there.

"The sun stood overhead when distant reports that seemed to come from the east wakened me. They sounded like gunshots. I leaped to the ground and limbered up the injured leg. After a first sharp pain, it became manageable, though it remained stiff and throbbed persistently, forcing me to limp a little.

"I kept to higher ground, where I had good vision in all directions. From time to time I saw small parties of natives. Once I heard and saw a squadron of airplanes to the northeast.

"In a couple of hours or so I reached a region of sheer rock escarpments, hills, deep ravines, and narrow passes. There were patches of dense, semitropical jungle around water holes. Elsewhere grew thickets of thorn, stunted trees, and sometimes sparse brown grass. I heard the movements of a considerable force ahead. Guided by the sounds, I struck off at a tangent and hid in the shadow of a large boulder atop a dolomite.

"Over the crest of a hill came native scouts, in advance of a detachment of white infantry and native troops. In all, the raiding party consisted of about two hundred, of whom three-fourths were native troops. They looked like Somalis to me.

"The white men, except for the officers, weren't tanned enough or lean enough to have been hardened by long fighting in the tropics. I judged them to be fairly recent arrivals. All were heavily armed.

"SUDDENLY a rifle cracked, then another. Intermittent shots poured from an ambush ahead. One of the white men fell. A couple of natives staggered when they were hit. The rest was merely efficient slaughter. Two machine guns went into action like magic and peppered the hillside thicket. There were a few answering shots. A few of the black defenders charged into the open. Mowed down by the fusillade, none of them escaped. About a dozen seemed to have been posted in the ambush.

"Red rage seethed inside of me. You have to see things like that in the wild, unknown places of the world to know the seamy side of colonial wars and imperial aggression. Twelve against two hundred—twelve armed with 1876 Springfields and muskets so ancient land rusty that they couldn't tell whether the pin would hit or the cartridge explode when they pulled the trigger—twelve against modern rifles, machine guns and grenades.

"It didn't make any difference that I'd stolen a treasure from Buala when I couldn't get it otherwise. At least I hadn't tried to kick him off of his own land or put a bullet through him when he couldn't see the deal my way. I was mad enough to start a one-man, or rather a one-panther, campaign against the whole detachment Idiotic? Sure. But here's how it worked out.

"I crept down from the dolomite and detoured ahead until I found a suitable spot for my purposes. At a V-neck that the column must pass and where the legend could not possibly be missed, I scratched on the ground:

WARNING! GO BACK!

The King of the Panthers.

"A quarter-mile beyond the V-neck, I jumped to the top of a great pile of fallen rocks, where I could easily be seen silhouetted against the sky. I had not waited long before the scouts found my message and my tracks. One of them ran back to the main body in great excitement. The others noticed me and stared at me. I stared at them. The moment I saw sunlight gleam on a rifle barrel swinging up, I dropped behind the rocks. Bullets whined past. I took a quick peek and saw a cluster of troops gesticulating and waving over my message.

"The native troops had obviously received a scare and the whites were trying to quiet their fears. It seemed as though they all saw me and turned toward me at once. There was a moment's complete silence, while I looked down toward them. Then I slipped away among the fallen masses of rock and the scrub thorn as more lead hornets buzzed.

"I doubled back by much the same route until I was well behind the raiders. Then I started. catching up with them again.

"I singled out a victim at the very tail of the column. Keeping well to the rear, I took advantage of every possible concealment until the right moment came, when he was temporarily cut off from the rest by a twist in the defile. He saw me just before I hit him. His eyes popped. He didn't have time to squawk. I landed on his shoulders, he slammed against rock, and when his skull hit there came the sharp snap of a neck breaking. I lifted his rifle between my teeth and got back in the brush. Then I let out a terrific screech. I watched just long enough to see several white and native troops rush back. Morale took another blow.

"I had the devil of a time lugging that rifle in a circuitous detour toward the head of the column. I had to stay well covered and at a distance or light gleaming on a barrel would have betrayed me. When I reached a vantage point, my leg was throbbing worse. I was striking for the last time in my one-panther campaign, and I determined to make it a telling shot.

"Beyond the V-neck stretched a valley that lay between rock bluffs. A number of mud-holes extended along the valley like beads on a string, each surrounded by grass, dwarf palms, and scrub. I got wind of a village somewhere ahead but the tribe had either moved on or taken to the hills for the time being. I set up shop, so to speak, on the highest of a series of broken and tumbled masses from the cliffs, a couple of miles from the V-neck.

"The sun was westering and the heat had begun to abate. The valley, at least to my eyes, had acquired a sinister reddish hue. In the quiet air, the sounds of the oncoming force gave an effect like the motions of puppets.

"I had laid the rifle between two rocks so that no gleam would show its presence. The rifle, the shadow, and I blended into one. I was amused to notice the newly acquired caution with which the raiding party advanced. I marked the figure which I hoped was the commanding officer.

"GETTING ready to fire that rifle was one of the hardest jobs I've ever tackled. I had no finger to squeeze the trigger. I could not hold the rifle against my shoulder. I couldn't use the sights. But I'd thought about all the difficulties when I was toting it, and I solved them after a sort. I drew back from the rifle and sighted along the rock groove in which it rested. Then I crawled up to it, shifted its angle, and drew back for another estimate until I had it aimed at a spot below a shoulder-high rock that the column would pass. I made these preparations, of course, before the detachment was in range. Then I lay on my side with the stock against my chest and the nail oi a paw hooked around the trigger.

"When the man I had marked stepped into range, I fired. The recoil gave a wallop to my ribs. The officer finished his step, raised a hand toward his ribs, and collapsed. I grabbed the rifle in my teeth and stepped into full view.

"The results were electrical. Silhouetted against the setting sun, I must have presented an awesome appearance. The whole column halted as one, then pandemonium broke out. The Somalis turned retreat into rout. Brave as they were, they couldn't face a panther-devil that wrote warnings and backed them up with deadly marksman-ship.

"Shouted commands were ignored. The officers shot down their own men in an effort to stop the panic. They fired at where I had been, but I had ducked.

"For months to come the survivors of that raiding party will, I hope, break into a cold sweat every time they hear a panther howl.

"My lone campaign struck me as a success, but I was weary, my leg ached severely, and night drew near. I decided to return to camp and see what I could do there. Further foraging in my present condition would have been simple suicidal.

"When the sun was ready to drop below the horizon, I had put several miles of the return trip behind me. I traveled clear of the jungle to make better time. Even so, my injured leg hindered me badly. I tried to keep my weight o? it by trotting along hippity-hop in a sort of three-legged gait.

"I glanced around when I heard the rush of hooves. A one-horned rhinoceros was charging me like a runaway express train. At the moment of impact it flung its lowered head skyward. Its horn, hooked around me, hurled me high in the air and backward. That terrific heave both saved my life and lost it. I went through the air in an arc and crashed among the branches of a low growing tree. I was knocked unconscious, but out of reach.

"When I opened my eyes, night had fallen. I was draped over a limb. The rhino had departed. Its horn had opened a gash in my side, the branches had cut and bruised me, and my right hind leg which had already taken punishment enough was broken.

"As I jumped to earth I gave a screech that would have brought my friend the rhino back in double-quick time if he had heard it. I couldn't help it, so fierce was the agony. All the rest of the night I spent in hopping and dragging my way back to camp. Only the memory of the emerald drove me on. Growing fainter with every step, and losing blood steadily, it was all I could do not to yield to the temptation to crawl into a thicket and die.

"Almost any creature that walked could have beaten me then. The jungle and all its noises, its mysterious life, the strange greenish dusk within it, and the scarlet moonlight filled me with terror. The way back seemed endless. The air smelled sulphurous. I sweltered in that infernal heat. Or perhaps it was only fever that crept over me as I toiled on the long route, fever and the slow finger of death."

In the silence that ensued, Burton, who had taken copious notes on the story, sat brooding for the period in which a man could smoke a pipe. Finally he sighed deeply. "I resent it after a fashion, that he should be first to have so remarkable an experience," he murmured. "By rights you or I should have been elect."

Travers said flatly, "I haven't your skill at surgery. I can't perform the operation and turn you loose, and I won't let you do the job on me."

"I'm afraid you haven't the true instincts of the martyr, Travers. Fame, adventure, pioneering—they mean nothing to you. If I were dependent upon your inclinations, doubtless we might never have passed this milestone on the road of human achievement. It was a stroke of genius, no less, the scientific genius that is today tearing apart the secrets of life, mind, and matter."

"And now that the milestone has been reached?"

"On to the next!" Burton tugged at his beard as he glanced at the sleeper. His expression was curious: a mixture of envy, of regret, and of inhumanly calculating in-tent.

He rose and began to make preparations. Travers did not finish the involuntary phrase that came to his lips. "You mean—?"

CHAPTER VI

THE END OF THE EMERALD GOD

FROM fever and the slow finger of death, from dreams and memories and lost realities hidden in mists afar, Leif Abbot slowly returned to consciousness. He was afraid to open his eyes through fear of what he would find, through fear that it would not be what he hoped to find.

He recalled Buala, the emerald, flight through jungle. The recollection was mixed up with fever and the impression of a nightmare in which he had somehow been imprisoned in the body of a panther. It had been a harrowing nightmare, too graphic and vivid.

Among his haze of thoughts drifted the faces of two white men who proclaimed themselves scientists but who mastered demoniac arts. Leif Abbot had an uncertain feeling that he had talked to them at considerable length, but he could not imagine what he had talked to them about. It was all hopelessly involved. He tried vainly to force the pictures into a consecutive sequence.

When he blinked his eyes open and saw his own body still lying upon the operating table, he felt only the dull unhappiness of one who has already been shocked into numbness. Assailed by forebodings, he looked down. His head moved with singularly abrupt and sudden jerks. When he saw the talons, the thin, horny legs, and the feathered body of a bird of prey, he screamed his fury. The result was a croak, harsh and forbidding.

Travers had left the tent. Burton, who was taking the pulse of the body, looked around when the eagle screamed.

"Awake?" he queried, his eyes alight with excitement. "Another triumph, a complete success! Leif Abbot, your body is mending but it still is not out of danger. You fortunately destroyed the black panther by putting its body to excessive strain. You have a very courageous nature, but you let it run away with your better judgment. We have given you a second temporary body. You have wings. You can fly. The skyways are open to you, while the spirit of the eagle is earthbound in your body.

"When you return, I trust that recovery has progressed sufficiently so that the identity of each can be restored to its rightful abode. The cage door is not locked. If you can hear me you are at liberty to open the door and depart. Return when you will, but I would advise you not to remain away for any extended period."

Leif Abbot had an insensate urge to fly straight at that ruddy face, hook his talons in the bushy black beard, and peck at the man's eyes. But out of the turmoil of his emotions, out of the need for radically readjusting himself to his environment, one thought stood clear. An opportunity other than the one specified had been unintentionally given him.

With mental prayers that Burton. would not divine his purpose, he used his beak to push the cage door aside. He strutted forth and stretched his wings experimentally to get the feel of them. By the easy response, he knew that the bird's natural motions and habits had carried over.

He struck instantly. A swoop brought him over the emerald figurine that lay among his belongings. He hovered, clutched it in his talons, and sailed for the tent flap. Burton lunged after him, shouting, "Come back here! Drop that, you idiot!"

His wingtips grazed the canvas and deflected his course. Burton almost caught up with him, but his outstretched hands just missed the eagle's tail feathers.

Then the bird soared.

A bullet buzzed by. Leif Abbot heard a loud report. He squinted earthward. Travers had appeared from nowhere. Running toward the tent, he whipped out his revolver and was emptying it at the flying target. There could be no doubt of his purpose. Only the emerald could have brought such greed to his eyes. He was willing to kill the eagle and the mortal spirit of Leif Abbot if necessary to prevent the loss of that treasure.

LEIF ABBOT swooped, swerved, darted in erratic arcs, mounted suddenly, side-slipped, nose-dived, and straightened out. No ordinary marksman could have hit so crazily veering a target. Only a miracle could have enabled even a superb shot to halt the eagle. Travers was not the marksman, and chance did not provide him the miracle. His bullets went wide of the bird. With his last triumphant glance and a scream of mirthless mockery, Abbot saw Burton struggling to wrest the pistol from Travers, a useless struggle now that the weapon was empty.

The figurine did not weigh enough to prove a hindrance. After the first thrill of flight and escape, he forgot about his prize. He felt a stronger emotion. A rapture gripped him, an ecstasy unlike anything he had yet known.

Many times during his life, when watching the wild ducks fly south on the Mid-Western prairies in autumn, while staring at seagulls as they circled a ship, or admiring the lightning-like speed of hummingbirds as they darted toward honey-flowers, he had envied the birds their winged freedom. He reveled in that freedom now. He rose ever higher, strong wings beating the way aloft. It took lass effort than he had imagined, for his wings slanted automatically to receive the full lifting power of every gust of wind and utilize each upward eddy.

He felt like a spirit liberated from all earthly ties. The jungle became only a dark mass below him. The landscape unfolded toward farther horizons. Trees, rocks, and water holes lost their individuality.

The ground evolved into masses and areas, a darker carpet for the jungle, a lighter area for the plain, a sun-capped, shadow-filled mass for the mountains.

He found himself flying toward those distant peaks that rimmed the northeastern horizon. In the midst of his breathless enjoyment and elation, he wondered why his course came so easily. Then he remembered a previous experience, and guessed that the nest of the eagle lay somewhere among those towering crags and gorges.

He was about to change his line of flight when his far-sighting gaze was drawn to the puzzling actions of three birds. The birds swooped to earth in single file, rose, looped over, and dipped again. It dawned on him that the birds were airplanes miles distant; and their maneuvers could best be explained if they were indulging in the luxury of ground-strafing.

Fifteen minutes later, drifting at an altitude of approximately a mile, he found his surmise correct. The airplanes, fast bombers equipped with machine guns, had evidently resorted to ground-strafing for lack of any considerable target worth bombing. He estimated the region to lie twenty miles north of where he had met the raiding column the day before. But it was only a guess, for small landmarks could not be distinguished at all from his height, and the large ones he viewed from a different perspective.

Gorges, basaltic extrusions, lava flows, and jagged hills formed the terrain, as though a giant hand had built turrets and scattered massive blocks in random formation. Why any nation should want that lonely, unlovely land mystified him. Even from his height, however, he detected tiny ants here and there on the hilltops, or crawling from bush to bush in the valley bottoms. He heard the stutter of machine guns and saw answering wisps of smoke puff up from the ground. Now and then one of the ants stopped crawling.

He spiraled lower, the peril from stray shots forgotten in the anger that again welled inside of him. Leif Abbot had more than one contradiction in his make-up. As a footloose adventurer and trader, he had always been alert to strike a shrewd bargain when he could; but he was just as eager to leap into fray on the side of the underdog when someone else was taking an unfair advantage.

Still circling downward, he wondered if there was anything he could do about the one-sided battle. His intentness on getting a closer view and his preoccupation with means of counterattack brought him to the danger zone before he realized it. The song of a sky-riding slug passed too close for comfort.

ONE of the bombers completed its power dive and its burst of firing. It zoomed upward for position. Its nose was tilted toward the eagle. Leif Abbot clearly saw the leather helmets of its crew, and a surprised expression behind the pilot's goggles as he noticed the eagle. Leif Abbot dropped the emerald figurine. It fell straight to its target.

There was a crash and a zing. Glittering green fragments and a flash of gold streaked the air. It was as though the propeller had rammed a stone wall.

The bomber leaped under its own momentum, lost speed, and went into a tailspin. It plunged toward the ground from its altitude of only a few hundred feet. The pilot frantically worked the controls and had just got the craft straightened out when it crashed.

All its bombs must have exploded at the instant of impact. A gigantic fountain of flame roared up. Grass and bushes flattened as a wall of wind rushed in. The concussion numbed Leif Abbot even before he felt the skyward surge. The air filled with blasted objects, débris, shards of metal, bits of flesh. The second bomber, diving to do its own ground-strafing in the wake of the first, was caught over that inferno, tossed as by invisible hands. Some hurtling missile must have struck the bomb rack, for the machine disintegrated in another great geyser of flame and smoke and erupting metal.

He never knew the fate of the third bomber. Tossed around in the violent currents from those blasts, he fought for control.

Then the world became quiet. It seemed to reel and grow fuzzy. His thoughts began to wander. How had he managed to hear at all? So far as he knew, birds were not equipped with auditory apparatus akin to man's, yet he had distinctly heard Burton speak.

His wings felt sticky. He wanted to fold them in and plummet to earth. It would be so easy. He could straighten out just before he crashed—but he wouldn't straighten out any more than the bomber. He didn't even know if he was flying in the camp's direction, but he kept to a straight line. The emerald was gone. Why should he go on, with the treasure for which he had endured so much shattered into a million irrecoverable bits? What insane impulse had made him throw it away? At least they wouldn't be able to take it away from him now.

LEIF ABBOT awakened from a dream that he had been flying through the air and sinking toward the green shadows of the jungle. He was not at all sure that he had wakened. Instead of flying, he found himself in suspension. He floated, not in air, but amid a denser medium. He saw the shadowy green twilight, but it was the obscurity of water, not of forests.

Beast, bird, fish—what did it matter? One nightmare was no worse than another. He had survived the others, and he would live through this, until the delirium left him and he opened his eyes again upon the world as he knew it.

Try as he might, he could not close his eyes, now that a measure of awareness had returned. While he was brooding, he was consciousness of somber twilight. As his thoughts became coherent, he was forced to abandon evasions.

Travers and Burton had cheated and betrayed him. They had used their fiendish discovery to deprive him of his rightful body for the third time. They had locked him up in the guise of a fish.

He tried to turn his head to see what sort of finny creature he had become, but his head would not turn. A flip of the fins and he faced the opposite direction. He rose, dived, circled, wriggled, and spun around until he was dizzy with exasperation. His eyes could see only forward and upward. He could not turn his head.

Had they placed him in the headwaters, the ground springs, that formed the source of the river he had followed in his original flight? He became aware of a gentle lazy current, and allowed himself to drift along.

The water swarmed with life. He was appalled by what his human eyes had missed when he had drunk of necessity at tepid pools and streams during his years in the tropics.

A great horror of these strange depths overcame him. He could not follow the stream to the sea. He could never watch beneath or behind. He had no weapon to fight lurking monsters. He had no desire to find out what terrifying life-forms infested the deeper parts of the river, or what rotting hulks and bones littered the sea-bottoms. Once he left his present position, he would never be able to find his way back.

A flip of the tail brought him face about. A fiercer horror assailed him, but he had no voice to cry out, no time to flee. A sort of dumb and paralyzing madness quaked through him as he saw the jaws of the crocodile close—

Burton looked worried. He watched the body of Leif Abbot which was twitching grotesquely. The arms and legs made spasmodic movements. The mouth gaped like that of a fish out of water.

The body ?opped weakly all at once, with a quiver and a horrible ?nality. Burton sprang to his kit, seized drugs, and worked for an hour in sweating anxiety. His e?orts produced no results.

"What happened?" asked Travers.

"I don't know. I'm afraid the vitality of the fish was of too low an order to direct a highly developed and complicated organism."

Travers filled his pipe irritably. "He was done for, no matter what. Why the devil couldn't he have left the emerald?"