Help via Ko-Fi

"SIGHT depends upon the etheric vibrations which we are wont to denominate light, said Professor Xenophon Xerxes Zapt, the eminent investigator of the unknown (sometimes called "Unknown Quantity Zapt" by his associates by reason of the double "X" in his name. He spoke from the reading chair wherein he had been browsing over the pages of a scientific journal, in the living-room of his home.

"Good thing it does, too," declared Bob Sargent, fiancé of the professor's daughter Nellie, surveying the young woman in appreciative fashion. "If it didn't, I suppose we couldn't see a thing."

"Exactly." The professor nodded. "There are times, Robert, when you have a gratifying manner of perceiving the main point of a deduction to be arrived at by the consideration of already established facts. Light being the main instrument of vision, its absence from the scheme of things would rob us of one of the five recognized senses beyond a doubt."

"And yet," said Bob, "they tell us that black is an absence of light, don't they, professor? So if they're right why is it we can see a negro—"

"Wait." The professor held up a slender hand. "We were speaking of light, not color, Robert."

Bob nodded. "Well, yes. But if black is an absence of color, why call the negro a colored man?"

Xenophon Xerxes Zapt indulged in a frown. Displeasure shone in his spectacled eyes. There were times when he disapproved strongly of Nellie's choice of a future husband—when he was more than a little annoyed by the particular sense of humor possessed by the young attorney. And now that annoyance flamed. "If it were not for the facetiousness you at times exhibit, Robert," he said with a sudden stiffness, "I would be far more satisfied as to the amount of light contained in what you are pleased to consider your mind. There are occasions, when in endeavoring to discuss some scientific problem in your presence, I am reminded of the saying in regard to casting pearls of price before—er —porcine appreciation. Levity is the last characteristic of personality with which we should approach the consideration of natural problems." He reached up and began pulling at the graying muttonchop whiskers on either side of his cleanly shaven chin.

Nellie gave Bob a warning glance, though her blue eyes were dancing.

And Sargent heeded the sign. "Well, really, professor," he said, "I had no intention of acting like the proverbial swine. Just what's the notion, will you explain?"

"Invisibility!" Xerxes Zapt pronounced the word with a force hardly to be expected from a man of so slight a frame. He was a little fellow, was the professor, customarily clad as now in baggy trousers, a loose coat and roomy slippers, in which he went puttering about the experiments that had won him a certain sort of fame.

"Invisibility," he repeated, eying Sargent. "Have you any conception, Robert, of all that may be embraced in that term?"

"Why—er," said Bob; "if a thing's invisible you can't see it—like a gas, or—"

"Exactly," the professor helped him out; "or the workings of some people's brains. Invisibility is the state wherein a substance defies the operation of the visible sense. What, then, if instead of arriving at such a state through the vaporization process as in the instance of a gas, substances should be rendered invisible, and at the same time their solidity were to be maintained?"

"It would be rather awkward, wouldn't it," Sargent suggested. "People would always be bumping into things."

"Eh?" Once more Xerxes Zapt eyed him in an almost suspicious manner.

"Well, perhaps—perhaps they would, Robert. And in that fact lies the advantage to be gained. Now this article on camouflage, I have been reading would make it appear that camouflage depends on the ability of man to present a baffling aspect of ordinary appearance to the perceptive centers of the brain, through the visual function of the optic nerve. Am I plain?"

"I believe that is the generally accepted explanation," Sargent assented weakly.

"Exactly. But what if, instead of changing the aspect of natural objects, they were rendered incapable of being seen?"

"Holy smoke!" said Bob and paused in sudden comprehension. "I guess I begin to get your notion."

Xenophon Xerxes Zapt leaned forward. "It would revolutionize the entire system of defense which might be employed by a nation. It would enable a fleet of an army to disguise its presence completely. I think it was known to the ancients. Merlin, whom Tennyson mentions, had a cloak of invisibility, you remember. Robert—my mind is made up. I am going to do it."

"Make things invisible?" Sargent questioned.

"Exactly." The professor rose and shook down his baggy trousers. "And when it is accomplished I am going to give it to this nation. The United States of America is going to be rendered—"

"Not invisible!" Robert interrupted.

"Certainly not." Zapt gave him a withering glance. "I was about to say that to Xenophon Xerxes Zapt it was reserved to render his nation impregnable from attack."

"By Jove, professor, that's a wonderful thing if you can do it," Robert exclaimed.

"If—if?" the professor bridled. "just so. In all ages progressive minds have had to contend with the doubt of scoffers."

Having delivered that parting shot, he turned and stalked from the room.

"Well"—Sargent looked at Nellie—"as long as he doesn't render you invisible, sweetness."

Miss Zapt glanced down at Fluffy, the beautiful Angora cat she was holding in her lap, tweaked one pink-tipped ear with her fingers and—flushed.

"If you don't quit making him cross he's apt to squirt some of it on you when he gets it finished," she cautioned.

Bob laughed. "Small danger. He's too wise. If he did that he couldn't tell when I was hanging around the prettiest little brown-haired girl in town."

And after that—well, quite a while after that—he said: "Good night."

Yet late as he departed, a light still burned in the room Professor Xenophon Xerxes Zapt had converted into a laboratory of sorts, on the second floor of his home.

A month went by, however, before anything came of the professor's scheme, and Sargent had put the thing completely out of his mind. Then on a certain evening he mounted the steps of the Zapt residence, found the door open, and save for the unguarded condition of the house, no sign of anybody home.

With the freedom of long acquaintance, he stepped inside and glanced around.

The sound of a soft voice calling struck his ears. "Fluffy—Fluffy—kitty—kitty— come here—come on and get your supper, honey. Drat it—where has the creature gone?"

Sargent grinned in pleasurable anticipation, and followed the sound to the rear. "Won't I do as well?" he questioned, entering the kitchen where Nellie was standing with a brimming bowl of milk in her hands.

"Oh, hello, Bob," she answered, turning toward him. "I can't imagine where she is. It's time she was fed, but she doesn't come when I call her."

"Oh, well, she'll come back. It's a way with cats," Bob told her. "Put the milk on the floor where she can get it when she does. I've got something for you."

"What?" Miss Zapt set down the bowl as he had suggested, and came to stand beside him, as he produced a box from his pocket, and from the box a ring.

"You said you admired it the other day when we saw it in a window."

"Bob!" Miss Zapt seized it and slipped it on a different finger from the one where her betrothal solitaire already blazed. And then she put her arm around Bob's neck and stood on tiptoe to kiss him.

Sargent met her halfway, lifted his head and stiffened a trifle, and stood holding her still in his arms, until at length he let out a slow ejaculation: "What the deuce!"

"What's the matter?" Nellie raised her eyes, then turned them in the direction his were already staring, to find them resting on the bowl she had placed on the floor.

And that was all—except that for some unaccountable reason—the milk was disappearing! Even as she stood as rigid now as Sargent—it's blue-white level went down!

"Bob!" she whispered in a tensely sibilant fashion; "do—do you see it?"

"That's the trouble," he said rather thickly. "I don't see a thing, and yet— that bowl of milk is going to be empty pretty soon."

And then as they stood arrested, scarcely breathing, it must be confessed, in the face of the inexplicable thing occurring before them, if they were to accept the evidence of their senses, Nellie's ears caught a faintly rhythmic sound.

"Listen!" Her blue eyes widened. Her hand crept up and laid hold of Sargent's fingers.

"Lap, lap—lap, lap." The milk sank lower and lower.

"Fluffy!" said Nellie all at once.

"Fluffy?" Bob repeated.

"Yes." Nellie set her soft pink lips together. "She's there—drinking that milk. I've got to catch her, but—don't you let go of my hand."

She began to tiptoe forward, and Sargent followed. "Fluffy," she wheedled softly. "Fluffy—honey." She bent her knees and reached out groping fingers. And suddenly she tore her hand from Sargent's grasp and made a swiftly clutching gesture. "I've got her," she announced and straightened.

"Where?" said Bob a trifle blankly.

"Right here. I'm holding her in my hands. Never mind, Fluffy—muddy's got you."

"Well—" Sargent accepted the information. "You sound like it, and you look as if you were holding something, but darned if I can see her."

"Of course not." Miss Zapt's tone was one of quickening exasperation. "Silly, don't you understand?"

"No, I don't," Bob said rather shortly, hesitated briefly and went on again in dawning comprehension. "Unless it's some more of your father's—"

"It is," Nellie declared with conviction. "That invisibility stuff he was talking about last month. And he's—he's tried it on Fluffy, and—" Her voice began to quiver.

"Good Lord! " Bob gasped. "Well, never mind, sweetheart. If he did it he can undo it. Where is he?"

"I don't kno-ow!" said Nellie in a fashion suddenly savage. "But—I'm going to find him and make him bring back my cat!" She turned and ran out of the kitchen, into the hall that led to the front of the house.

Sargent caught up with her in' a stride. For a moment he had felt shaken, by the uncanny way in which the milk had vanished, but now that he knew the explanation, the whole aspect of things was altered. He grinned as Nellie raced ahead, apparently holding nothing to her bosom. And then he put out a hand and drew her to a stand.

"Listen!" he said.

"Swish! Swi-i-ish!" A fresh sound broke upon their ears.

"What is it?" Nellie questioned as the thing continued.

Bob shook his head. "If you ask me, somebody's washing the front of the house with a hose."

"Father!" Miss Zapt emitted the one brittle word, shook off Sargent's detaining hand and darted toward the swishing noise.

Bob followed—just as he had been following Nellie ever since he knew her first. Side by side they reached the front door.

Side by side they paused and gasped as a sweeping spray of fluid met them.

"Swish! Swi-i-i-ish!" Again the deluge.

"Get back!" Half-blinded, Bob reached for Nellie, caught her and dragged her to him. "Get back!"

As he turned to regain the protection of the hallway, he had a blurring vision of a slender figure with muttonchop whiskers and spectacle-rimmed eyes, playing the drenching liquid toward them from a length of rubber tubing; then—

"Swish! Swi-i-i-ish!" The stream caught them again—this time in the back, and— he found himself apparently still holding Nellie's arm, but—Miss Zapt had disappeared.

"Nellie!" he faltered. It was unbelievable. He could touch her, but he couldn't see her!

"Bob—oh, Bob—where are you?" He heard her.

"Right here," he said as a horrible thought laid hold upon him. "Nellie—can't you see me-dear?"

"No-o-o. I can feel your—fingers," she whimpered. "But—I—oh, Bob—I'm so wet and—frightened. You—you just faded out —all at once, after—father—"

"Father? Yes, father," was the answer.

Sargent saw the whole thing all at once. Father had decided to make a. practical demonstration of his new invention or discovery, or whatever one wanted to call it—and he had started spraying the infernal stuff on the house. Well—it was his house, and he could do what he pleased about it, but when it came to using the thing on human beings—

Father's voice cut into his swirling consideration: "Robert—am I right in thinking I saw you and Nellie on the porch just now?"

Bob turned. The little man had switched the direction of his hose and was staring toward the house with nearsighted eyes.

"You're dead right, you saw us," he flung back a none-too-gentle answer. "But you can't see us now. You turned that confounded stream into our faces, and—"

"Why bless my soul—I didn't see you," said Zenophon Xerxes Zapt; "not until it was too late—that is—then I thought I saw you—and then you disappeared."

"Exactly," Bob agreed, very much as Zapt himself might have done it. "That's exactly what we did."

"Tum around then, Robert," the professor advised. "The substance only blots out what it touches."

"We did that, too. We turned around and were blotted out about the time you gave the porch its third dose," Bob rejoined, and paused in consternation. All at once he became aware that he couldn't see the porch floor or the steps, or Nellie, or himself. About all he seemed able to see was the little man standing there on the lawn squirting some sort of diabolical fluid out of the hose he now perceived came down from the laboratory window. And without the least warning he found that the sight filled him with a sort of quickly upflaring rage.

In a rush he was off the porch, which seemed to be there, whether he could see it or not, and flinging himself toward the source of his and its disappearance.

"Put down that hose!"

"Robert, to whom are you speaking?" Professor Zapt peered toward the changing sound of Sargent's voice.

"I'm speaking to you," Bob told him almost roughly. "Put down that hose or turn it off, or—something."

"Remarkable—remarkable," said the professor, smiling. "Robert, I cannot see you, though I hear you plainly. You appear to be actually very near me. If anything had been needed to clearly demonstrate the unqualified success of my recent investigations, this—"

"Put down that hose!" Bob said it for the third time and seized the rubber tubing in his hands.

And for some reason best known to himself, Professor Xenophon Xerxes Zapt chose to resist. He struggled to retain possession of the hose, exerting his frailer strength against that of the unseen, yet stronger man who was dragging on it. He tugged and Bob tugged, and all at once the professor lost his balance and sprawled upon the ground, while the nozzle released from his controlling guidance, whipped round like a serpent striking, and drenched him to the skin.

"Oh, I say, professor, I didn't mean to do that," began Bob, and broke off—because apparently he was speaking to nothing. Professor Xenophon Xerxes Zapt had vanished.

From the porch where she had been an unseen watcher Nellie screamed the one word "Father!"

Sargent put down the hose and groped toward where he had last seen "father" on the ground.

"Father!" Once more Miss Zapt was calling.

And Sargent's fingers made contact with something clammily wet and very active that bounced away from his touch and emitted a most irascible exclamation. "There, now, you impudent young whelp, see what you have done!"

"I—I can't—professor," Bob stammered, straightening and drawing a hand across his seemingly useless eyes. "I can hear you all right, but I can't see you."

"Father!"

"Yes, yes," Zapt answered his daughter's frantic query. "I'm—I'm all right, my dear."

"But—I can't see you—or Bob—or myself. Where are you?"

"Here. Sargent, where are you?"

"Here."

"Why bless my soul," said the professor. "We'd better get into the house and talk this over. Nellie where are you?"

"Right here where Bob left me," said Nellie in a tone of incipient hysterics.

"Well, stay there, and we'll come to you," Sargent advised her. "I can't see the porch or the steps, but I can make out the door. Are you there, professor?"

"Of course I'm here," Zapt assured him none too sweetly.

"Then come along." Bob began moving toward what was still visible of the house, feeling with shuffling feet for the vanished steps, in order to ascend them to the equally vanished porch, where Nellie waited, to all appearances no more than a disembodied voice.

"Bob!" that voice came to him.

"Here—coming," he answered, and found the steps, and went gropingly up, hands outstretched before him. "Nellie?"

"Here!"

Beside the door he found her. She gasped as he touched her.

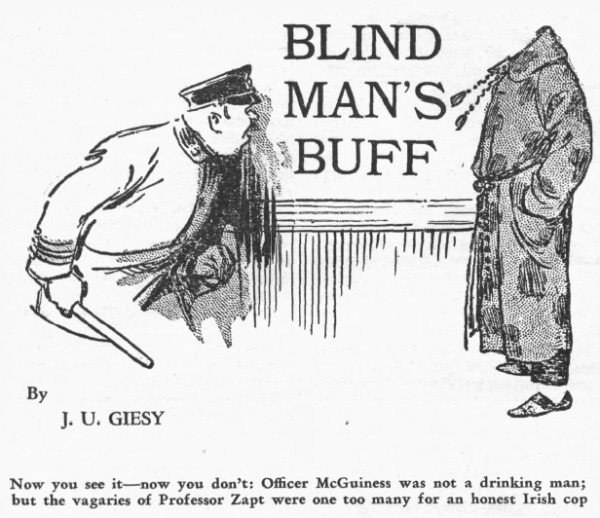

"It's all right now," he said, "I've got you. Talk about blind-man's buff!"

Behind him came a sound of two objects colliding, and the professor cried: "Ouch!"

"Father!" Miss Zapt stiffened inside the arm Bob had slipped about her; "did you hurt yourself?"

"Not irreparably, my dear," said Zapt in somewhat sarcastic fashion. "And I trust I have not badly damaged the steps. Where in thunder are you?"

"Right here by the door."

"Huh!" The sound of tentative footsteps came nearer. "All right—now I touch you."

"As a matter of fact," said Sargent, "that's my hand you're holding, but it's all the same. I'm holding Nellie. We'd better stick together."

The professor grunted and removed his clutching fingers. "We'd better get some place where we can locate ourselves by means of definitely known objects. Go into the living-room," he said.

They passed inside. At least they could now see where they were going. They gained the door of the living-room and passed through it. Bob led Nellie to the couch and seated himself beside her.

"Father, where are you?" she inquired. "Here," came the voice of the professor. "In my usual chair, my dear. I presume you can see it, at least. Sargent, what are you doing?"

"I'm holding Nellie's hand." Bob told him the literal truth.

Xenophon Xerxes Zapt quite audibly sniffed. "At least," said he, "I can't see you."

"Well—you've nothing on me there, professor," Bob retorted. "Here's a pretty kettle of fish."

"Exactly," complained the protessor. "If you young people hadn't interfered—"

"That's hardly the point now," Sargent interrupted. "The question now seems to be, how do we get rid of the stuff?"

For a time Xerxes Zapt made no answer, and then he sighed. "That is the point, Robert, of course," he assented. "But you see, I hadn't gone into it fully, and—"

"Father!" Nellie's voice cut into his confession.

"See here," Sargent half rose and sank back as her panic-tightened fingers held him. "Do you mean we've—got to stay-like this, till you think up an answer?"

"That's it, Robert," said Xenophon Xerxes Zapt in a tone he plainly strove to make soothing. "I think that I had—er—that I had better try to think."

Nellie began laughing. There was nothing of humor in the sound. It was just the cachinnation of jangled nerves and ended in a sob.

Bob put his arms about her and drew her head against his shoulder.

"Don't leave me, Bob," she murmured. "Promise me not to leave this house till I see you again."

"I won't," said Sargent. "I won't leave till your father has thought of something to get us all out of this fix." He drew his arms tightly about her shaking figure, and held her. The situation was rather eerie, to say the least. He could see everything in the room quite plainly—everything, but the professor, and Nellie, and himself.

And yet the sound of another sigh wafted to him from the reading chair beside the table, where presumably Zapt was thinking. It was followed by mumbled words: "Milk?—no—certainly not. Benzine?—scarcely. Ether?—"

"Ether ought to do it," Sargent caught up the suggestion. "You said it was etheric vibrations that were responsible for sight."

The professor grunted again, but made no further comment. Silence came down again. Dusk had fallen. The sound of shuffling footfalls struck on Sargent's ears—he snap of a switch. A sudden illumination filled the living-room and hallway. Plainly Zapt had turned on the lights. Bob listened while he padded back again to his chair and sank into it with a creaking of springs.

And then Zapt was speaking: "All things considered, Robert, I think we had best go upstairs and change our clothes."

"Simple? It was as simple as that. Bob saw it in a flash. "Of course," he exclaimed, as Nellie stirred in his embrace at her father's words, "that will be all right for you and Nellie, but I haven't any extra clothes here, myself."

"I can lend you a bathrobe, Robert," Zapt replied. "Such a step will at least give us an opportunity to once more establish ourselves. The solution being mainly on our clothing, either their removal or their covering with an unsaturated texture, will render us visible in a major extent, even if it does not restore the visibility of our faces and hands. And, of course, I shall think of something in time. Alcohol might do it—"

"Exactly." Judging by sounds, the professor rose. "You will come with me, Robert. Nellie will go to her room."

"Come, dear," Robert prompted and helped Nellie to her feet. And then, as the fall of a heavy body, followed by inarticulate grunts and mouthings and mumbles came from the front porch, he paused.

The sounds went on. They might have been a scuffle to judge by their nature, or they might have been occasioned by some object trying to right itself. There was a clumping reminiscent of heavily shod feet —the rasp of stertorous breathing—then—

"Phwat th' divil?" a self-interrogation.

"Sssh!" One could fancy Xenophon Xerxes Zapt was the source of the sibilant warning. "Officer McGuiness. He's noticed the house, confound him. Quick now before he comes inside! Upstairs!"

In his last statement, Professor Xenophon Xerxes Zapt had been absolutely right. Danny McGuiness, large, florid, Irish, and a careful officer, had noticed the house, as a matter of course—as during his hours of duty patrolling the street on which it stood, he noticed it and half a hundred others every time he passed. And tonight as he approached it, just after dusk and the assumption of his tour of duty, he had noticed something about it, such as he had never beheld in all of his life.

He came to a halt and stared. And then quite slowly he lifted a massive hand and passed it across his eyes. Seemingly, he was gazing upon the roof and the second story of a house, without visible means of support, as the judge of the city court was wont to say of certain individuals brought before him. The roof and the upper story were quite familiar. Danny had seen them every night for many months, since the night he saw them first, but—the rest of the picture had disappeared. Everything below that strangely buoyant part of the structure was seemingly wiped out, very much as a drawing might have been sponged from a slate.

Hence Danny's instinctive gesture to his eyes. He knew he couldn't be seeing what they said he was. He had heard of such catastrophes overtaking a man in the past. Hemi—or semi—or something like that, the doctors called it. Anyway, a man saw only half of what he looked at, and quite plainly he was seeing—or he wasn't seeing—something like half of Professor Zapt's house.

He put down his hand and laid hold of the fence that ran in front of Professor Zapt's yard. All at once, regardless of the roof and upper story of the mansion at which he was staring, Danny felt a need of support. For a moment he stood clinging to it, and then—he decided on a test. Slowly he turned his vision away from the floating superstructure of a modern residence, and directed it across the street.

Then he let go of the fence and drew a long breath. He could see the other side of the street all right-all of it. Under such conditions his eyes did nothing by halves. He could see the houses from top to bottom, the boles as well as the tops of the street-fringing trees. Then-what in the name of all sense was the answer? Perhaps a temporary seizure merely—something he had eaten, maybe, that had caused a passing semiblindness. He turned back and once more faced in the original direction, and stiffened before the original effect.

"Well, sa-a-y!" said Officer McGuiness, and decided that the trouble must be with the house and not himself. He decided, also, to investigate.

He knew Xenophon Xerxes Zapt. Several times before he had known the professor to produce some odd results by his experiments—had even profited by them to some extent, when Zapt had seen fit to hand him sundry bits of neatly engraved paper, as a mark of appreciation of the interest Danny had displayed. Having recovered from his first shock of surprise, McGuiness was half-minded that he was facing some such condition now.

"Funny little feller," he muttered to himself, as he went up the walk from the gate. "Always fussin' wid some sort of contraption. Lookit this now, wull ye—lookit—hull bottom of th' house gone —rest of it floatin'—"

Abruptly he collided with something and sprawled forward on what felt, even if it did not look like the steps of the missing porch.

For a moment he lay with the breath nearly shaken out of him, and then he began to feel tentatively about.

"They're here—even if I can't see 'em," he decided at last, the conviction driven into him by his fall and the verdict of his groping touch. "They're here, but—phwy is ut, I can't see 'em? Shure, now I'm here, I'll mention ut to th' perfissor. 'Tis a dangerous state of affairs indade, whin an honest man can't see where he's goin', an' moighty near breaks his neck."

Whereupon McGuiness got up and felt his way with searching feet to the top of the steps, and across the equally invisible porch, to the oblong of the door, beyond which glowed the lighted hallway. It was all most peculiar to be walking on something he couldn't see, and despite him, it affected Danny oddly.

"Phwat th' divil?" he voiced his bewilderment in a heavy rumble and stiffened in his tracks at a warning "Sssh!"

It was a sound of caution—a sibilant plea for quiet.

Danny considered quickly. His official instincts wakened. He strained his ears. The rasp of whispering came to him.

"Sssh! is ut—whisper—whisper? Be gob there's somethin' moighty funny goin' on about this house." Danny thought the words rather than spoke them, gave over his first intention of ringing the bell if he could find it, laid hold of the screen door and dragged it open and stepped inside.

The hall ran straight back before him. He saw the upward sweep of a flight of stairs. To the right lay an archway giving into a lighted apartment. McGuiness turned toward it, made his way into the living-room and gazed about him. So far as he could see he stood alone in a room otherwise deserted, and yet-dimly it seemed to him that he detected a sound of suppressed breathing.

He frowned. It was like being in a darkened room with some unknown person— only this room was brilliantly lighted and still he could perceive no one. A peculiar tingling, prickling sensation began to run up and down his spine. Somebody had whispered, and they must have been close indeed, for him to have heard it—somebody or something was breathing not ten feet from him. He was sure of it now.

The pad of a careful footfall! He whirled, tightening his grip on his club-to find nothing at all—or at least no one, before his starting eyes.

And yet that softly padding sound went on. It was as though unseen enemies were creeping upon him. Tiny drops of moisture started on his cleanly shaven upper lip. He spun about again at a rustle of movement from a new direction. His respiration quickened. A few moments ago his eyes had tricked him and now, seemingly, he couldn't believe his ears. Or could he? Those whispers—of breathing—of unseen footfalls were all about him. Surely someone or something was moving in the room. Something? McGuiness began to lose some of his ruddy color. He wasn't a coward, but this unseen, this unknown, this apparently unknowable thing was getting on his nerves.

"Father?"

He jerked himself up at the sound of the articulated word—no more than another sibilant sighing, but none the less something within his comprehension.

"Sssh!"

There it was again—that plea for silence—caution—from the hallway now, or else his ears had utterly failed him.

He twisted himself toward it. "Perfissor —are ye there, perfissor?" he questioned hoarsely and advanced on legs that shook the least bit for all his dogged effort to control them. At the worst, he told himself now, he was facing something human.

And yet, when he reached the hallway and groped along it, searching, searching heavily for what he couldn't see, there was no one, and—a stairboard creaked. He lifted his eyes quickly. He could see the stairs and—there was nothing on them!

All at once McGuiness found himself shaken by something like a chill, and clenched his teeth.

"Aw go to th' divil," he snarled a gritting surrender, "shure an' I wasn't hired to go chasin' after ghosts."

A giggle—an unmistakable giggle—was wafted to him from the second story. And yet to his baffled imagination it was the gibbering of a disembodied something. Kicking open the screen door he stepped outside, removed his helmet to draw a none too steady. hand across a sweat-dampened forehead, and took a deep and somewhat uncertain breath. Then very slowly he found the steps and went down them, retraced his way along the walk to the street, and turned to look back at what he could see of the house.

It was just the same as it had been, only now McGuiness knew that no matter how it appeared, the bottom part was there, and—it wasn't the same after all—there was a light upstairs!

He regarded it for several minutes before he understood. When he had gone inside it had not been there—and there was that creak on the stairs! Somebody had whispered "father," and somebody had "sshed" the speaker into silence, and— somebody had giggled when he said he wasn't chasing ghosts—and the recollection of that giggle wasn't at all the same now as it had seemed inside the house. It had been a sound of amusement with nothing of menace about it. The officer was greatly puzzled.

All at once Danny McGuiness set his Irish jaw in determination. "Begob," he declared to no one but himself, "I'm go-in' to get to th' botthom of this now, do ye moind. I couldn't see anywan at all, at all, but—by th' same token I couldn't see th' steps. An' yit, I found thim."

Jerking open the gate, he found the steps again with groping feet, went up them and reached the door and let himself once more inside.

Upstairs, he told himself. Upstairs he would find them. He would go up, and this time he'd demand an explanation. Sshes would not deter him any longer. There was somebody up there. Ghosts didn't turn on lights. He'd go up and find the lighted room, and—

Something brushed against his leg!

He started, checked himself, and stooped swiftly with reaching fingers. They closed on something furry—something silken soft—something that drew back and emitted an unmistakable hiss.

"A cat!" said Danny. "A kitty, d'ye moind now—an' I can't see her—I can't see her any more than I could thim steps— but—I can feel her—or I could. Kitty-kitty—come here, kitty." Still bent he began feeling in all directions, turning on heavy feet as he sought to come once more in contact with her. "Come, kitty—come to Officer McGuiness. Where th' divil did you go to?"

"Why, officer, such language! I'm surprised."

McGuiness straightened slowly. He glanced upward, quite to the head of the stairs—and remained staring while his heavy jaw sagged.

Because something stood then—only it was hard to say what it was—except that it appeared like the dress of a woman—just that—just a dress leaning a little toward him across the railing. Or no. There seemed to be a pair of feet beneath it-a pair of feet, but neither hands nor head! There was nothing at all above the neck of the garment save a little triangular spot, as white as—as white as a virgin reputation. And that was all. There wasn't anything else. There was just that tiny white triangle, and a pair of feet, and the dress.

So much he saw and then the dress was joined by two other garments—a jerkily moving bathrobe and a suit of clothes. The three formed a group and began descending.

"Whuroo!" Danny let the sound out of his chest in a sighing exhalation and stood watching. But it wasn't a battle-cry of combat—it was just the last stand of conscious volition. And after that, as the three headless figures marched down the stairs toward him, Officer Danny McGuiness was volitionally paralyzed. He stared with a never-shifting vision, but he neither spoke nor moved. He was past all speech or movement, until, suddenly—the lady's garment laughed.

"Why, officer," it said, "you look as if you were seeing a ghost."

Hope waked anew in Danny McGuiness's breast. He stiffened his shaking knees. The voice had nothing of whispers, of "sshes" about it. It had a distinctly human note. It sounded suspiciously like that of Professor Zapt's daughter.

"Shure, I—I don't know what I'm seein'," he stammered. "Fer th' lasht fifteen minutes ut's been pretty much now you see it an' now you don't wid me, miss-but mostly don't."

"Of course." And surely that was Xenophon Xerxes Zapt's voice emerging from the suit of clothes. "That's the substance on our faces, McGuiness. Come into the living-room and I'll explain the matter to your better understanding."

"All roight, perfissor," Danny assented. "It is yersilf, isn't ut, per?ssor?"

"Of course," said the suit of clothes. "An—th'—th' bathrobe?" Danny questioned.

"Mr. Sargent," said the lady's garment.

"Av course," accepted Danny. "I moight hov knowed it, if I hadn't been so—surprised."

"Come on in and sit down while father explains it," the bit of rayon crepe said. And Danny followed while it led him in and gave him a chair, and seated itself on the couch at the bathrobe's side.

"You see, officer, I have discovered a substance which, applied to any object, nullifies sight," began the suit of clothes.

McGuiness nodded. "Shure, I don't know phwat nullyfies means, unless you put ut on th' steps, an' used phwat was left on yersilves an' th' cat."

"Exactly," the suit of clothes responded. "I suppose you noticed the house?"

"I did thot-phwat there was of ut, so far as I could see," said Danny. " 'Twas that made me come in to see was I goin' bloind or phwat. Was ut you sshed when I was standin' on th' porch?"

"Yes," the suit of clothes replied. "We were just going upstairs to get some fresh garments so we could see ourselves, at least in a measure." They went on and explained fully what had occurred.

Danny grinned when the narrative was finished. "D'ye mean," said he, "thot you don't know yit phwat wull take ut off?"

"Exactly," the suit of clothes admitted in a somewhat apologetic manner.

"Nellie seems to be coming out of it better than the rest of us, anyway," the bathrobe suggested. "I can see her nose."

"I—I powdered it! " The lady's garment giggled.

"Powdered ut?" All at once Danny chuckled. That explained the white triangle above the garrnent's neck. Everything was coming clear at last.

"But see here, perfissor," he inquired, turning to where the suit of clothes was sitting rather limply in the chair beside the table. "Won't ut wash?"

"Wash?" the suit of clothes made irascible rejoinder. "Of course it will wash. It has to wash. I've been thinking about whether it will wash best in a solution of naphtha or gasoline. I—"

"But—I was speakin' of wather," Oificer McGuiness interrupted.

"Water!" The suit of clothes literally bounded upright. "Why—why bless my soul! I dissolved the reagents in water. Water will take it off, of course! Here-" There was a brief pause and suddenly a neatly engraved bit of paper was seemingly floating just below the end of a sleeve extended in Danny's direction. "McGuiness, you're a wonder. Take this as a little mark of my appreciation of your assistance. I er—frankly, McGuiness, I never before realized that you had a scientific mind."

Officer McGuiness took it. He rose. "I'll be gettin' back on my beat now," said he. "But I'm shure glad to have been of assistance to ye, perfissor, an' I'm glad I understand th' sityation, or I reckon I'd be spendin' this here now to have a. doctor examine my eyes."

"Well—all's well that ends well," remarked the bathrobe.

Danny, moving toward the hallway, paused.

"Thrue for ye, Mister Sargent, an' if you'll accept th' suggestion—maybe besides washin' yer hands an' faces, ut would be as well to use a little wather on th' front of th' house."