Help via Ko-Fi

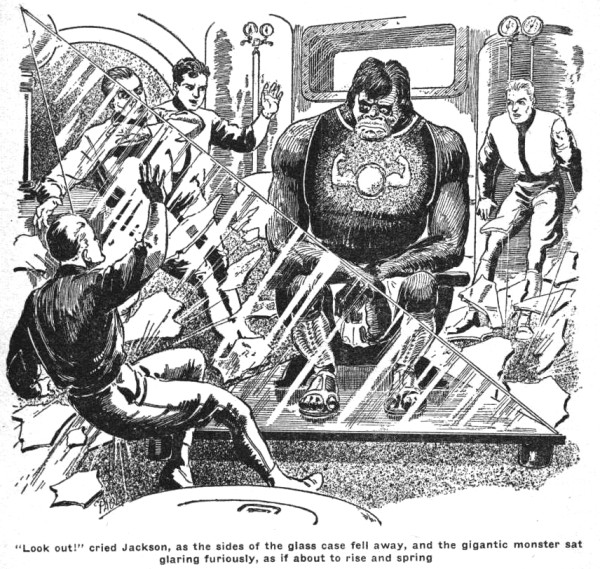

| All powerful Strokor, the iron-voiced dictator of Mercury when the Earth was young, wanted Ave, the girl who was different, to be his wife and mother a new race. Edam, the dreamer, the man who looked like Ave, Strokor feared not—and that was his fatal mistake. |

The Lord of Death

By HOMER EON FLINT

Author of "The Planeteer," etc.; co-author of "The Blind Spot"

A Complete Novelet

Part I

The Discovery

CHAPTER I

THE SKY CUBE

THE doctor, who was easily the most musical of the four men, sang in a cheerful baritone:

"The owl and the pussycat went to sea

In a beautiful, pea-green boat."

The geologist, who had held down the lower end of a quartet in his university days, growled an accompaniment under his breath as he blithely peeled the potatoes. Occasionally a high-pitched note or two came from the direction of the engineer; he could not spare much wind while clambering about the machinery, oilcan in hand. The architect, alone, ignored the famous tune.

"What I can't understand, Smith," he insisted, "is how you draw the electricity from the ether into this car without blasting us all to cinders."

The engineer squinted through an opal glass shutter into one of the tunnels, through which the anti-gravitation current was pouring. "If you don't know any more about buildings than you do about machinery, Jackson," he grunted, because of his squatting position, "I'd hate to live in one of your houses!"

The architect smiled grimly. "You're living in one of 'em right now, Smith," said he; "that is, if you call this car a house."

Smith straightened up. He was an unimportant-looking man, of medium height and build, and bearing a mild, good-humored expression. Nobody would ever look at him twice, would ever guess that his skull concealed an unusually complete knowledge of electricity and mechanisms.

"I told you yesterday, Jackson," he said, "that the air surrounding the earth is chock full of electricity. And—"

"And that the higher we go, the more juice," added the other, remembering. "As much as to say that it is the atmosphere, then, that protects the earth from the surrounding voltage."

The engineer nodded. "Occasionally it breaks through, anyhow, in the form of lightning. Now, in order to control that current, and prevent it from turning this machine, and us, into ashes, all we do is to pass the juice through a cylinder of highly compressed air, fixed in this wall. By varying the pressure and dampness within the cylinder, we can regulate the flow."

The builder nodded rapidly. "All right. But why doesn't the electricity affect the walls themselves? I thought they were made of steel."

The engineer glanced through the dead-light at the reddish disk of the earth, hazy and indistinct at a distance of forty million miles. "It isn't steel; it's a nonmagnetic alloy. Besides, there's a layer of crystalline sulphur between the alloy and the vacuum space."

"The vacuum is what keeps out the cold, isn't it?" Jackson knew, but he asked in order to learn more.

"Keeps out the sun's heat, too. The outer shell is pretty blamed hot on that side, just as hot as it is cold on the shady side." Smith seated himself beside a huge electrical machine, a rotary converter which he next indicated with a jerk of his thumb. "But you don't want to forget that the juice outside is no use to us, the way it is. We have to change it.

"It's neither positive nor negative; it's just neutral. S0 we separate it into two parts; and all we have to do, when we want to get away from the earth or any other magnetic sphere, is to aim a bunch of positive current at the corresponding pole of the planet, or negative current at the other pole. Like poles repel."

"Listen easy," commented Jackson. "Too easy."

"Well, it isn't exactly as simple as all that. Takes a lot of apparatus, all told." And the engineer looked about the room, his glance resting fondly on his beloved machinery.

The big room, fifty feet square, was almost filled with machines; some reached nearly to the ceiling, the same distance above. In fact, the interior of the "cube" had very little waste space. The living quarters of the four men who occupied it had to befitted in wherever there happened to be room. The architect's own berth was sandwiched in between two huge dynamos.

He was thinking hard. "I see now why you have such a lot of adjustments for those tunnels," meaning the six square tubes which opened into the ether through the six walls of the room. "You've got to point the juice pretty accurately."

"I should say so." Smith led the way to a window, and the two shaded their eyes from the lights within while they gazed at the ashy glow of Mercury, toward which they were traveling. "I've got to adjust the current so as to point exactly toward his northern half." Smith might have added that a continual stream of repelling current was still directed toward the earth, and another toward the sun, away over to their right; both to prevent being drawn off their course.

"And how fast are we going?"

"Four or five times as fast as mother earth; between eighty and ninety miles per second. It's easy to get up speed out here, of course, where there's no air resistance."

Another voice broke in. The geologist had finished his potatoes, and a savory smell was already issuing from the frying pan. Years spent in the wilderness had made the geologist a good cook, and doubly welcome as a member of the expedition.

"We ought to get there tomorrow, then," he said eagerly. Indoor life did not appeal to him, even under such exciting circumstances. He peered at Mercury through his binoculars. "Beginning to show up fine now."

THE builder improved upon Van Emmon's example by setting up the car's biggest telescope, one of unusual excellence. All three pronounced the planet, which was three-fourths "full" as they viewed it, as having pretty much the appearance of the moon.

"Wonder why there's always been so much mystery about Mercury?" pondered the architect invitingly.

"Mercury is so close to the sun," answered the scientist, "that he's always been hard to observe. For a long time the astronomers couldn't even agree that he always keeps the same face toward the sun, like the moon toward the earth."

"Then his day is as long as his year?"

"Eighty-eight of our days; yes."

"Continual sunlight! He can't be inhabited, then?" The architect knew very little about the planets, but he possessed remarkable ability as an amateur antiquarian.

Dr. Kinney shook his head. "Not at present, certainly."

Instantly Jackson was alert. "Then perhaps there were people there at one time?"

"Why not?" the doctor put it lightly. "There's little or no atmosphere there now, of course, but that's not saying there never has been. Even if he is such a little planet—less than three thousand, smaller than the moon—he must have had plenty of air and water at one time, the same as the earth."

"What's become of the air?" Van Emmon wanted to know. Kinney eyed him in reproach. He said:

"You ought to know. Mercury has only two-fifths as much gravitation as the earth; a man weighing a hundred and fifty back home would be only a sixty-pounder there. And you can't expect stuff as light as air to stay forever on a planet with no more pull than that, when the sun is on the job only thirty-six million miles away."

"About a third as far as from the earth to the sun," commented the engineer. "By George, it must be hot!"

"On the sunlit side, yes," said Kinney. "On the dark side it is as cold as space itself—four hundred and sixty below, Fahrenheit."

They considered this in silence for some minutes. After a while the builder came back with another question.

"If Mercury ever was inhabited, then his day wasn't as long as it is now, was it?"

"No," said the doctor. "In all probability he once had a day the same length as ours. Mercury is a comparatively old planet, you know; being smaller, he cooled off earlier than the earth, and has been more affected by the pull of the sun. But it's been a mighty long time since he had a day like ours. Before the earth was cool enough to live on, probably."

"But since Mercury was made out of the same batch of material—" prompted the geologist.

"No reason, then, why life shouldn't have existed there in the past!" exclaimed the architect, his eyes sparkling with the instinct of the born antiquarian. He glanced up eagerly as the doctor coughed apologetically and said:

"Don't forget that, even if Mercury is part baked and part frozen, there must be a region in between which is neither." He picked up a small globe from the table and ran a finger-completely around it from pole to pole. "So. There must be a narrow band of country where the sun is only partly above the horizon, and where the climate is temperate."

"Then"—the architect almost shouted in his excitement, an excitement only slightly greater than that of the other two—,"then if there were people on Mercury at one time—"

The doctor nodded gravely. "There may be some there now!"

CHAPTER II

A DEAD CITY

FROM a height of a few thousand miles Mercury, instead of the craters, which always distinguished the moon, showed ranges of bona fide mountains.

The sky-car was rapidly sinking nearer and nearer the planet; already Smith had stopped the current with which he had attracted the cube toward the little world's northern hemisphere, and was now using negative voltage. This, in order to act as a brake, and prevent them from falling to destruction.

Suddenly, Van Emmon, the geologist, whose eyes had been glued to his binoculars, gave an exclamation of wonder. "Look at those faults!" He pointed toward a region south of that for which they were bound; what might be called the planet's torrid zone.

At first it was hard to see; then, little by little, there unfolded before their eyes a giant, spiderlike system of chasms in the strange surface beneath them. From a point almost directly opposite the sun, these cracks radiated in a half-dozen different directions; vast, irregular clefts, they ran through mountain and plain alike. In places they must have been hundreds of miles wide, while there was no guessing as to their width. For all that the four in the cube could see, they were bottomless.

"Small likelihood of anybody being alive there now," commented the geologist skeptically. "If the sun has dried it out enough to produce faults like that, how could animal life exist?"

"Notice, however," prompted the doctor, "that the cracks do not extend all the way to the edge of the disk." This was true; all the great chasms ended far short of the "twilight band" which the doctor had declared might still contain life.

But as the sky-car rushed downward their attention became fixed upon the surface directly beneath them, a point whose latitude corresponded roughly with that of New York on the earth. It was a region of low-lying mountains, decidedly different from various precipitous ranges to be seen to the north and east. On the west, or left-hand side of this district, a comparatively level stretch, with an occasional peak or two projecting, suggested the ancient bed of an ocean.

By this time they were within a thousand miles. Smith threw on a little more current; their speed diminished to a safer point, and they scanned the approaching surface with the greatest of care.

"Do either of you fellows see anything green?" demanded the engineer, a little later. They were silent; each had noticed, long before, that not even near the poles was there the slightest sign of vegetation.

"No chance unless there's foliage," muttered the doctor, half to himself. The builder asked what he meant. He explained: "So far as we know, all animal life depends upon vegetation for its oxygen. Not only the oxygen in the air, but that stored in the plants which animals eat. Unless there's greenery—"

He paused at a low exclamation from Smith. The engineer's eyes were fixed, in wonder and excitement, upon that part of the valley which lay at the joint of the "L" below them. It was perhaps six miles across; and all over the comparatively smooth surface jutted dark projections. Viewed through the glasses, they had a regular uniform appearance.

"By Jove!" exclaimed the doctor, almost in awe. He leaned forward and scrubbed the deadlight for the tenth time.

All four men strained their eyes to see. It was the architect who broke the silence which followed. The other three were content to let the thrill of the thing have its way with them. Such a feeling had little weight with the expert in archeology.

"Well," he declared jubilantly in his boyish voice, "either I eat my hat or that's a city!"

AS SWIFTLY as an elevator drops, and as safely, the cube shot straight downward. Every second the landscape narrowed and shrunk, leaving the remaining details larger, clearer, sharper. Bit by bit the amazing thing below them resolved itself into a real metropolis.

Within five minutes they were less than a mile above it. Smith threw on more current, so that the descent stopped; and the cube hung motionless in space.

For another five minutes the four men studied the scene in nervous silence. Each knew that the others were looking for the same thing—some sign of life. A little spot of green, or possibly something in motion—a single whiff of smoke would have been enough to cause a whoop of joy.

But nobody shouted. There was nothing to shout about. Nowhere in all that locality apparently was there the slightest sign that any save themselves were alive.

Instead, the most extraordinary city that man ever laid eyes upon was stretched directly beneath. It was grouped about what seemed to be the meeting-point of three great roads, which led to this spot from as many passes through the surrounding hills. And the city seemed thus naturally divided into three segments, of equal size and shape, and each with its own street system.

For they undoubtedly were streets. No metropolis on earth ever had its blocks laid out with such unvarying exactness. This Mercurian city contained none but perfect equilateral triangles, and the streets themselves were of absolutely uniform width.

The buildings, however, showed no such uniformity. On the outskirts the blocks seemed to contain nothing save odd heaps of dingy, sun-baked mud. On the extreme north, however, lay five blocks grouped together, Whose buildings, like those in the middle of the city, were rather tall, square-cut and of the same dusty, cream-white hue.

"Down-town" were several structures especially prominent for their height. They towered to such an extent, in fact, that their upper windows were easily made out. Apparently they were hundreds of stories high!

Here and there on the streets could be seen small spots, colored a darker buff than the rest of that dazzling landscape. But not one of the spots was moving.

"We'll go down further," said the engineer tentatively, in a low tone. There was no comment. He gradually reduced the repelling current, so that the sky-car resumed its descent.

They sank down until they were on a level with the top of one of those extraordinary skyscrapers. The roof seemed perfectly flat, except for a large, round, black opening in its center. No one was in sight.

When opposite the upper rows of windows, at a distance of perhaps twenty feet, Smith brought the car to a halt, and they peered in. There were no panes; the windows opened directly into a vast room. But nothing was clearly visible in the blackness save the outlines of the openings in the opposite walls.

They went down further, keeping well to the middle of the space above the street. At every other yard they kept a sharp lookout for the inhabitants; but so far as they could see, their approach was entirely unobserved.

When within fifty yards of the surface, all four men made a search for cross-wires below. They saw none; there were no poles, even. Neither, to their astonishment, was there such a thing as a sidewalk. The street stretched unbroken by curbing, from wall to wall and from corner to corner.

As the cube settled slowly to the ground, the adventurers left the deadlight to use the windows. For a moment the view was obscured by a swirl of dust; raised by the spurt of the current. Then this cloud vanished, settling to the ground with astounding suddenness, as though jerked down by some invisible hand.

Directly ahead of them, perhaps a hundred yards, lay a yellowish-brown mass of unusual octagonal shape. One end contained a small oval opening, but the men from the earth looked in vain for any creature to emerge from it.

The doctor silently set to work with his apparatus. From an airtight double-doored compartment he obtained a sample of the ether outside the car; and with the aid of previously arranged chemicals, quickly learned the truth.

There was no air. Not only was there no oxygen, the element upon which all known life depends, but there was no nitrogen, no carbon dioxide. Not the slightest trace of water vapor or of the other less known elements which can be found in small amounts in our own atmosphere. Clearly, as the doctor said, whatever air the astronomers had observed must exist on the circumference of the planet only, and not in this sun-blasted, north-central spot.

On the outer walls of the cube, so arranged as to be visible through the windows, were various instruments. The barometer showed no pressure. The thermometer, a specially devised one which used gas instead of mercury, showed a temperature of six hundred degrees, Fahrenheit.

No air, no water, and a baking heat; as the geologist remarked, how could life exist there? But the architect suggested that possibly there was some form of life, of which men knew nothing, which could exist under such circumstances.

They got out three of the suits. These were a good deal like those worn by divers, except that the outer layer was made of nonconducting aluminum cloth, flexible, airtight and strong. Between it and the inner lining was a layer of cells, into which the men now pumped several pints of liquid oxygen. The terrific cold of this chemical made the heavy flannel of the inner lining very welcome; while the oxygen itself, as fast as it evaporated, revitalized the air within the big, glass-faced helmet.

Once safely locked within the clumsy suits, Jackson, Van Emmon, and Smith took their places within the vestibule; while the doctor, who had volunteered to to stay behind, watched them open the outer door. With a hiss all the air in the vestibule rushed out; and the doctor earnestly thanked his stars that the inner door had been built very strongly.

The men stepped out on to the ground. At first they moved with great care, being uncertain that their feet were weighted heavily enough to counteract the reduced gravitation of the tiny planet. But they had been living in a very peculiar condition, gravitationally speaking, for the past three days; and they quickly adapted themselves.

After a little shifting about, the three artificial monsters gave their telephone wires another scrutiny. Then, keeping always within ten feet of each other, so as not to throw any strain on the connections, they strode in a matter-of-fact way toward the nearest doorway.

For a moment or two they stood outside the queer, peaked archway, their glimmering suits standing out oddly in the blinding sunlight. Then they advanced boldly into the opening. In a flash they vanished from the doctor's sight, and the inklike blackness of the opening again stared at him from that dazzling wall.

CHAPTER III

THE HOUSE OF DUST

THE geologist, strong man that he was, and by profession an investigator of the unknown—Van Emmon—took the lead. He stalked straight ahead into a vast space which, without any preliminary hallway, filled the entire triangular block. Before their eyes were accustomed to the shadow-"Pretty cold," murmured the architect into the phone transmitter. It was fastened to the inside of the helmet, directly in front of his mouth, while the receiver was placed beside his ear. All three stopped short to adjust each other's electrical heating apparatus. To do this, they did not use their fingers directly; they manipulated ingenious nonmagnetic pliers attached to the ends of fingerless, insulated mittens.

Before they had finished, the builder, who had been puzzling over the extraordinary suddenness with which that cloud of dust had settled received an inspiration. He was carrying notebook and camera. With his pliers he tore out a sheet from the former, and holding book in one hand and the leaf in the other, he allowed them to drop at the same instant.

They reached the ground together.

"See?" The architect repeated the experiment. "Back home, where there's air, the paper would have floated down. It would have taken three times as long for it to fall as the book."

Smith nodded, but he had been thinking of something else. He said gravely: "Remember what I told you—it's air that insulates the earth from the ether. If there's no air here"—he glanced out into the pitiless sunlight—"then I hope there's no flaw in our insulation. We're walking in an electrical bath."

They looked around. Objects were pretty distinct now. They could easily see that the floor was covered with what appeared to be machines, laid out in orderly fashion. Here, however, as outside, everything was coated with that fine, cream-colored dust. It filled every nook and cranny; it stirred about their feet with every step.

The geologist led the way down a broad aisle, on either side of which towered immense machinery. Smith was for stopping to examine them one by one; but the others vetoed the engineer's passion, and strode on toward the end of the triangle. More than anything else, they looked for the absent population to show itself.

Suddenly Van Emmon stopped short. "Is it possible that they're all asleep?" He added that, even though the sun shone steadily the year around, the people must take times for rest.

But Smith stirred the dust with his foot and shook his head. "I've seen no tracks. This dust has been lying here for weeks, perhaps months. If the folks are away, then they must be taking a community vacation."

At the end of the aisle they reached a small, railed-in space, strongly resembling what might be seen in any office on the earth. In the middle of it stood a low, flat-topped desk, for all the world like that of a prosperous real-estate agent, except that it was about half a foot lower. There was no chair. For lack of a visible gate in the railing, the explorers stepped over, being careful not to touch it.

There was nothing on top of the desk save the usual coat of dust. Below, a very wide space had been left for the legs of whoever had used it. And flanking this space were two pedestals, containing what looked to be a multitude of exceedingly small drawers. Smith bent and examined them; apparently they had no locks. He unhesitatingly reached out, gripped the knob of one, and pulled.

Noiselessly, instantaneously, the whole desk crumbled to powder.

Startled, Smith stumbled backward, knocking against the railing. Next instant it lay on the floor, its fragments scarcely distinguishable from what had already covered the surface. Only a tiny cloud of dust arose, and in half a second this had settled.

The three looked at each other significantly. Clearly, the thing that had just happened argued a great lapse of time since the user of that desk officiated in that enclosure. It looked as though Smith's guess of "weeks, perhaps months," would have to be changed to years, perhaps centuries.

"Feel all right?" asked the geologist. Jackson and Smith made affirmative noises; and again they stepped out, this time walking in the aisle along the outer wall. They could see their sky-car plainly through the ovals.

Here the machinery could be examined more closely. They resembled automatic testing scales, said Smith. The kind that are used in weighing complicated metal products after finishing and assembling. Moreover, they seemed to be connected, the one to the other, with a series of endless belts. These, Smith thought, indicated automatic production. To all appearances, the dust-covered apparatus stood just as it had been left when operations ceased, an unguessable length of time before.

SMITH showed no desire to touch the things now. Seeing this, the geologist deliberately reached out and scraped the dust from the nearest machine. To the vast relief of all three, no damage was done. The dust fell straight to the floor, exposing a streak of greenish-white metal.

Van Emmon made another tentative brush or so at other points, with the same result. Clean, untarnished metal lay beneath all that dust. Clearly it was some nonconducting alloy. Whatever, it was, it had successfully resisted the action of the elements all the while that such presumably wooden articles as the desk and railing had been steadily rotting.

Emboldened, Smith clambered up on the frame of one of the machines. He examined it closely as to its cams, clutches, gearing, and other details significant enough to his mechanical training. He noted their adjustments, scrutinized, the conveying apparatus, and came back carrying a cylindrical object which he had removed from an automatic chuck.

"This is what they were making," he remarked, trying to conceal his excitement. The others brushed the dust from the thing, a huge piece of metal which would have been too much for their strength on the earth. Instantly they identified it.

It was a cannon shell.

Again Van Emmon led the way. They took a reassuring glance out the window at the familiar cube, then passed along the aisle toward the farther corner. As they neared it they saw that it contained a small enclosure of heavy metal scrollwork, within which stood a triangular elevator.

The men examined it as closely as possible, noting especially the extremely low stool which stood upon its platform. The same unerodable metal seemed to have been used throughout the whole affair.

When they returned to the heap of powdered wood which had been the desk, Smith spied a long workbench under a nearby window. There they found a very ordinary vise, in which was clamped a piece of metal. But for the dust, it might have been placed there ten minutes before. On the bench lay several tools, some familiar to the engineer and some entirely strange. A set of screwdrivers of various sizes caught his eye. He picked them up, and again experienced the sensation of having wood turn to dust at his touch. The blades were whole.

Still searching, the engineer found a square metal chest of drawers, each of which he promptly opened. The contents were laden with dust, but he brushed this off and disclosed a quantity of exceedingly delicate instruments. They were more like dentists' tools than machinists', yet plainly were intended for mechanical use.

One drawer held what appeared to be a roll of drawings. Smith did not want to touch them; with infinite care he blew off the dust with the aid of his oxygen pipe. After a moment or two the surface was clear, but it offered no encouragement; it was the blank side of the paper.

There was no help for it. Smith grasped the roll firmly with his pliers—and the next second gazed upon dust.

In the bottom drawer lay something that aroused the curiosity of all three. These were small reels, about two inches in diameter and a quarter of an inch thick, each incased in a tight-fitting box. They resembled measuring tapes to some extent, except that the ribbons were made of marvelously thin material. Van Emmon guessed that there were a hundred yards in a roll. Smith estimated it at three hundred. They seemed to be made of a metal similar to that composing the machines. Smith pocketed them all.

Under the bench they discovered a very small machine, decidedly like a stock ticker, except that it had no glass dome, but possessed at one end a curious metal disk about a foot in diameter. Apparently it had been undergoing repairs; it was impossible to guess its purpose. Smith's pride was instantly aroused; he tucked it under his arm, and was impatient to get back to the cube, where he might more carefully examine this find with the tips of his fingers.

It was when they were about to leave the building that they thought to inspect walls and ceiling.

"Look at that dust again! How'd it get there?" Van Emmon paused while the others, the thought finally getting to them, felt a queer chill striking at the backs of their necks. "Men—there's only one way for the dust to settle on a wall! It's got to have air to carry it! It couldn't possibly get there without air!

"That dust settled long before life appeared on the earth, even! It's been there ever since the air disappeared from Mercury!"

CHAPTER IV

THE LIBRARY

"I THOUGHT you'd never get back," complained the doctor crossly, when the three entered. They had been gone just half an hour.

Next moment he was studying their faces, and at once he demanded the most important fact. They told him, and before they had finished he was halfway into another suit. He was all eagerness; but somehow the three were very glad to be inside the cube again, and firmly insisted upon moving to another spot before making further explorations.

Within a minute or two the cube was hovering opposite the upper floor of the building the three had entered. With only a foot of space separating the window of the sky-car and the dust-covered wall, the men from the earth inspected the interior at considerable length. They flashed a searchlight all about the place, and concluded that it was the receiving room, where the raw iron billets were brought via the elevator, and from there slid to the floor below. At one end, in exactly the same location as the desk Smith bad destroyed, stood another, with a low and remarkably broad chair beside it.

So far as could be seen, there were neither doors, window-panes, nor shutters through the structure. "To get all the light and air they could," guessed the doctor. "Perhaps that's why the buildings are all triangular; most wall surface in proportion to floor area, that way."

A few hundred feet higher they began to look for prominent buildings.

"We ought to learn something there," the doctor said after a while, pointing out a particularly large, squat, irregularly built affair on the edge of the "business district." The architect, however, was in favor of an exceptionally large, high building in the isolated group previously noted in the "suburbs." But because it was nearer, they maneuvered first in the direction of the doctor's choice.

The sky-car came to rest in a large plaza opposite what appeared to be the structure's main entrance.

The doctor was impatient to go. Smith was willing enough to stay behind; he was already joyously examining the strange machine he had found. Two minutes later Kinney, Van Emmon, and Jackson were standing before the portals of the great building.

There they halted, and no wonder. The entire face of the building could now be seen to be covered with a mass of carvings; for the most part they were statues in bas relief. All were fantastic in the extreme, but whether purposely so or not, there was no way to tell. Certainly any such work on the part of an earthly artist would have branded him either as insane or as an incomprehensible genius.

Directly above the entrance was a group which might have been labeled, "The Triumph of the Brute." An enormously powerful man, nearly as broad as he was tall, stood exulting over his victim, a less robust figure, prostrate under his feet. Both were clad in armor.

The victor's face was distorted into a savage snarl, startlingly hideous by reason of the prodigious size of his head, planted as it was directly upon his shoulders; for he had no neck. His eyes were set so close together that at first glance they seemed to be but one. His nose was flat and apelike in type, while his mouth, devoid of curves, was revolting in its huge, thick-lipped lack of proportion. His chin was square and aggressive; his forehead, strangely enough, extremely high and narrow, rather than low and broad.

His victim lay in an attitude that indicated the most agonizing torturer his head was bent completely back, and around behind his shoulders. On the ground lay two battle-axes, huge affairs almost as heavy as the massively muscled men who had used them.

But the eyes of the explorers kept coming back to the fearsome face of the conqueror. From the brows down, he was simply a huge, brutal giant; above his eyes, he was an intellectual. The combination was absolutely frightful. The beast looked capable of anything, of overcoming any obstacle, mental or physical, internal or external, in order to assert his apparently enormous will. He could control himself or dominate others easily.

"It can't be that he was drawn from life," said the doctor, with an effort. It wasn't easy to criticize that figure, lifeless though it was. "On a planet like this, with such slight gravitation, there is no need for such huge strength. The typical Mercurian should be tall and flimsy in build, rather than short and compact."

But the geologist differed. "We want to remember that the earth has no standard type. Think what a difference there is between the mosquito and the elephant, the snake and the spider! One would suppose that they had been developed under totally different planetary conditions, instead of all right on the same globe.

"No; I think this monster may have been genuine." And with that the geologist turned to examine the other statuary.

Without exception, it resembled the central group; all the figures were neckless, and all much more heavily built than any people on earth. There were several female figures; they had the same general build, and in every case were so placed as to enhance the glory of the males. In one group the woman was offering up food and drink to a resting worker. In another she was being carried off, struggling, in the arms of a fairly good-looking warrior.

Dr. Kinney led the way into the building. As in the other structure, there was no door. The space seemed to be but one story in height, although that had the effect of a cathedral. The whole of the ceiling, irregularly arched in a curious, pointed manner, was ornamented with grotesque figures. The walls were also partially formed of squat, semihuman statues, set upon huge, triangular shafts. In the spaces between these outlandish pilasters there had once been some sort of 'decorations. A great many photos were taken here.

As for the floor, it was divided in all directions by low walls. About five and a half feet in height, these walls separated the great room into perhaps a hundred triangular compartments, each about the size of an ordinary living-room. Broad openings, about five feet square, provided free access from one compartment to any other. The men from the earth, by standing on tiptoes, could see over and beyond this system.

"Wonder if these walls were supposed to cut off the view?" speculated the doctor. "I mean, do you suppose that the Mercurians were such short people as that?" His question had to go unanswered.

They stepped into the nearest compartment, and were on the point of pronouncing it bare, when Jackson, with an exclamation, excitedly brushed away some of the dust and showed that the presumably solid walls were really chests of drawers. Shallow things of that peculiar metal, these drawers numbered several hundred to the compartment. In the whole building there must have been millions.

ONCE more the dust was carefully removed, revealing a layer of those curious rolls or reels, exactly similar to what had been found in the tool chest in the shell works. A careful examination of the metallic tape showed nothing whatever to the naked eye, although the doctor fancied that he made out some strange characters on the little boxes themselves.

His view was shortly proved. Finding drawer after drawer to contain a similar display, varying from one to a dozen of of the diminutive ribbons, Van Emmon adopted the plan of gently blowing away the dust from the faces of the drawers before opening them. This revealed the fact that each of the shallow things was neatly labeled.

Instantly the three were intent upon the fresh clue. The markings were very faint and delicate, the slightest touch being enough to destroy them. To the untrained eye, they resembled ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. To the archeologist, they meant that a brand-new system of ideographs had been found.

Suddenly Jackson straightened up and looked about with a new interest. He went to one of the square doorways and very carefully removed the dust from a small plate on the lintel. He need not have been so careful; engraved in the solid metal was a single character, plainly in the same language as the other ideographs.

The architect smiled triumphantly into the inquiring eyes of his friends. "I won't have to eat my hat," said. he. "This is a sure-enough city, all right, and this is its library!"

Smith was still busy on the little machine when they returned to the cube. He said that one part of it had disappeared, and was busily engaged in filing a bit of steel to take its place. As soon as it was ready, he thought, they could see what the apparatus meant.

The three had brought a large number of the reels. They were confident that a microscopic search of the ribbons would disclose something to bear out Jackson's theory that the great structure was really a repository for books, or whatever corresponded with books on Mercury.

"But the main thing," said the doctor enthusiastically, "is to get over to the 'twilight band.' I'm beginning to have all sorts of wild hopes."

Jackson urged that they first visit the big "mansion" on the outskirts of this place; he said he felt sure, somehow, that it would be worth while. But Van Emmon backed up the doctor, and the architect had to be content with an agreement to return in case their trip was futile.

Inside of a few minutes the cube was being drawn steadily over toward the left or western edge of the planet's sunlit face. As it moved, all except Smith kept close watch on the ground below. They made out town after town, as well as separate buildings. And on the roads were to be seen a great many of those octagonal structures, all motionless.

After several hundred miles of this, the surface abruptly sloped toward what had clearly been the bed of an ocean. No sign of habitation here, however. So, apparently, the water had disappeared after the humans had gone.

This ancient sea ended a short distance from the district they were seeking. A little more travel brought them to a point where the sun cast as much shadow as light on the surface. It was here they descended, coming to rest on a sunlit knoll which overlooked a small, building-filled valley.

According to Kinney's apparatus, there was about one-fortieth the amount of air that exists on the earth. Of water vapor there was a trace; but all their search revealed no human life. Not only that, but there was no trace of lower animals; there was not even a lizard, much less a bird. And even the most ancient-looking of the sculptures showed no creatures of the air; only huge, antediluvian monsters were ever depicted.

They took a great many photos as a matter of course. Also, they investigated some of the big, octagonal machines in the streets, finding them to be similar to the great "tanks" used in war, on earth, except that they did not have the caterpillar tread. Their eight faces were so linked together that the entire affair could roll, alter a jolting, slab-sided, flopping fashion. Inside were curious engines, and sturdy machines designed to throw the cannon-shells the visitors had seen. No explosive was employed, apparently, but centrifugal force generated in whirling wheels. Apparently these cars, or chariots, were universally used.

The explorers returned to the cube, where they found that Smith, happening to look out a window, had spied a pond not far off. The three visited it and found, on its banks, the first green stuff they had seen; a tiny, flowerless salt grass, very scarce. It bordered a slimy, bluish pool of absolutely still fluid. Nobody would call it water. They took a few samples of it and went back.

And within a few minutes the doctor slid a small glass slide into his microscope, and examined the object with much satisfaction. What he saw was a tiny, gelatin-like globule; among scientists it is known as the amoeba. It is the simplest form of life—the so-called "single cell." It had, been the first thing to live on that planet, and apparently it was also the last.

CHAPTER V

THE CLOSED DOOR

AS THEY neared Jackson's pet "mansion" each man paid close attention to the intervening blocks. For the most part these were simply shapeless ruins; heaps of what had once been, perhaps, brick or stone.

Apparently the locality they were approaching had been set aside as a very exclusive residence district for the elite of the country. Possibly it contained the homes of the royalty, assuming that there had been a royalty. At any rate the conspicuous structure Jackson had selected was certainly the home of the most important member of that colony.

When the three, once more in their helmets and suits, stood before the low, broad portico which protected the entrance to that edifice, the first thing they made out was an ornamental frieze running across the face. In the same bold, realistic style as the other sculpture, there was depicted a hand-to-hand battle between two groups of those half savage, half cultured monstrosities. And in' the background was shown a glowing orb, obviously the sun.

"See that?" exclaimed the doctor. "The size of that sun, I mean! Compare it with the way old Sol looks now!"

They took a single glance at the great ball of fire over their heads; nine times the size it always seemed at home, it contrasted sharply with the rather small ball shown in the carvings.

"Understand?" the doctor went on. "When that sculpture was made, Mercury was little nearer the sun than the earth is now!"

The builder was hugely impressed. He asked, eagerly: "Then probably the people became as highly developed as we?"

Van Emmon nodded approvingly, but the doctor was opposed. "No; I think not, Jackson. Mercury never did have as much air as the earth, and consequently had much less oxygen. And the struggle for existence," he went on, watching to see if the geologist approved each point as he made it, "the struggle for life is, in the last analysis, a struggle for oxygen.

"So I would say that life was a pretty strenuous proposition here, while it lasted. Perhaps they were—" He stopped, then added: "What I can't understand is, how did it happen that their affairs came to such an abrupt end? And why don't we see any—er—indications?"

"Skeletons?" The architect shuddered. Next second, though, his face lit up with a thought. "I remember reading that electricity will decompose bone in time." And then he shuddered again as his foot stirred that lifeless, impalpable dust.

As they passed into the great house the first thing they noted was the floor, undivided, dust-covered, and bare, except for what had perhaps been rugs. The shape was the inevitable equilateral triangle. And, here, with a certain magnificent disregard for precedent, the builders had done away with a ceiling entirely, and instead had sloped the three walls up till they met in a single point, a hundred feet overhead.

In one corner a section of the floor was elevated perhaps three feet above the rest, and directly back of this was a broad doorway, set in a short wall. The three advanced at once toward it.

Here the electric torch came in very handy. It disclosed a poorly lighted stair, way, very broad, unrailed, and preposterously steep. The steps were each over three feet high.

"Difference in gravitation," said the doctor, in response to Jackson's questioning look. "Easy enough for the old-timers, perhaps." They struggled up the flight as best they could, reaching the top after over five minutes of climbing.

Perhaps it was the reaction from this exertion; at all events each felt a distinct loss of confidence as, after regaining their wind, they began to explore. Neither said anything about it to the others; but each noted a queer sense of foreboding, far more disquieting than either of them had felt when investigating anything else. It may have been due to the fact that, in their hurry, they had not stopped to eat.

The floor they were on was fairly well lighted with the usual oval windows. The space was open, except that it contained the same kind of dividing walls they had found in the library. Here, however, each compartment contained but one opening, and that not uniformly placed. In fact, as the three noted with a growing uneasiness, it was necessary to pass through every one of them in order to reach the corner farthest from the ladderlike stairs. Why it should make them uneasy, neither could have said.

WHEN they were almost through the labyrinth, Van Emmon, after standing on tiptoes for the tenth time, in order to locate himself, noted something that had escaped their attention before. "These compartments used to be covered over," he said, for some reason lowering his voice. He pointed out niches in the walls, such as undoubtedly once held the ends of heavy timbers. "What was this place. anyhow? A trap?"

Unconsciously they lightened their steps as they neared the last compartment. They found, as expected, that it was another stairway. Van Emmon turned the light upon every corner of the place before going any further; but except for a formless heap of rubbish in one corner, it was bare as the rest of the floor.

Again they climbed, this time for a much shorter distance; but Jackson, slightly built chap that he was, needed a little help on the steep stairs. They were not sorry that they had reached the uppermost floor of the mansion. It was somewhat better lighted than the floor below, and they were relieved to find that the triangular compartments did not have the significant niches in their walls. Their spirits rose perceptibly.

At the corner farthest from the stairs one of the walls rose straight to the ceiling, completely cutting off a rather large triangle, The three paid no attention to the other compartments, but went straight to what they felt sure was the most vital spot in the place. And their feelings were justified with a vengeance when they saw that the usual doorway in this wall was protected by something that had, so far, been entirely missing everywhere else.

It was barred by a heavy door.

For several moments the doctor, the geologist, and the architect stood before it. Neither would have liked to admit that he would just as soon leave that door unopened. All the former uneasiness came back. It was all the more inexplicable, with the brilliant sunlight only a few feet away, that each should have felt chilled by the place.

"Wonder if it's locked?" remarked Van Emmon. He pressed against the dust-covered barrier, half expecting it to turn to dust; but evidently it had been made of the time-defying alloy. It stood firm. And it seemed nearly airtight.

"Well!" said the doctor suddenly, so that the other two started nervously. "The door's got to come down; that's all!" They looked around; there was no furniture, no loose piece of material of any kind. Van Emmon straightway backed away from the door about six feet, and the others followed his example.

"All together!" grunted the geologist; and the three aluminum-armored monsters charged the door. It shook under the impact; a shower of dust fell down; and they saw that they had loosened the thing.

"Once more!" This time a wide crack showed all around the edge of the door, and the third attempt finished the job. Noiselessly—for there was no air to carry the sound—but with a heavy jar which all three felt through their feet, the barrier went flat on the floor beyond.

At that same instant a curious, invisible wave, like a tiny puff of wind, floated out of the darkness and passed by the three men from the earth. Each noticed it, but no one mentioned it at the time. Van Emmon was already searching the darkness with the torch.

Apparently it was only an anteroom. A few feet beyond was another wall, and in it stood another door, larger and heavier than the first. The three did not stop; they immediately tried their strength on this one also.

After a half dozen attempts without so much as shaking the massive affair—"It's no use," panted the geologist, wishing that he could get a handkerchief to his forehead. "We can't loosen it without tools."

Jackson was for trying again, but the doctor agreed with Van Emmon. They reflected that they had been away from Smith long enough, anyhow. The cube was out of sight from where they were.

Van Emmon turned the light on the walls of the anteroom, and found, on a shelf at one end, a neat pile of those little reels, eleven in all. He pocketed the lot. There was nothing else.

Jackson and Kinney started to go.

"Look here," Van Emmon said in a low, strained voice. They went to his side, and instinctively glanced behind them before looking at what lay in the dust.

It was the imprint of an enormous human foot!

THE first thing that greeted the ears of the explorers upon taking off their suits in the sky-car, was the exultant voice of Smith. He was too excited to notice anything out of the way in their manner. He was almost dancing in front of his bench, where the unknown machine, now reconstructed, stood belted to a small electric motor.

"It runs!" he was shouting. "You got here just in time!" He began to fumble with a switch.

"What of it?" remarked the doctor in the bland tone which he kept for occasions when Smith needed calming. "What will it do if it does run?"

The engineer looked blank. "Why—" Then he remembered, and picked up one of the reels at random. "There's a clamp here just the right size to hold one of these," he explained, fitting the ribbon into place and threading its free end into a loop on a spool which looked as though made for it. But his excitement had passed; he now cautiously set a small anvil between himself and the apparatus. And then, with the aid of a long stick, he threw on the current.

For a moment nothing happened, save the hum of the motor. Then a strange, leafy rustling sounded from the mechanism. Next, without any warning, a high-pitched voice, nasal and plaintive but distinctly human, spoke from the big metal disk.

The words were unintelligible. The language was totally unlike anything ever heard on the earth. And yet, deliberately if somewhat cringingly, the voice proceeded with what was apparently a recitation.

As the thing went on the four men came closer and watched the operation of the machine. The ribbon unrolled slowly; it was plain that, if the one topic occupied the whole reel, then it must have the length of an ordinary book chapter. And as the voice continued, certain dramatic qualities came out and governed the words, utterly incomprehensible though they were. There was a real thrill to it.

After a while they stopped the thing. "No use listening to this now," as the doctor said. "We've got to learn a good deal more about these people before we can guess what it all means."

And yet, although all were hungry, on Jackson's suggestion they tried out one of the "records" that was brought from that baffling room. Smith was very much interested in that unopened door, and he and Van Emmon were in the midst of discussing it when Jackson started the motor.

The geologist's words stuck in his throat. The disk was actually shaking with the vibrations of a most terrific voice. Prodigiously loud and powerful, its booming, resonant bass smote the ears like the roll of thunder. It was irresistible in its force, compelling in its assurance, masterful and strong to an overpowering degree. Involuntarily the men from the earth stepped back.

On it roared and rumbled, speaking the same language as that of the other record; but whereas the first speaker merely used the words, the last speaker demolished them. One felt that he had extracted every ounce of power in the language, leaving it weak and flabby, unfit for further use. He threw out his sentences as though done with them. Not boldly, not defiantly, least of all, tentatively. He spoke with a certainty and force that came from a knowledge that he could compel, rather than induce his hearers to believe.

It took a little nerve to shut him off; Van Emmon was the one who did it. Somehow they all felt immensely relieved when the gigantic voice was silenced; and at once began discussing the thing with great earnestness. Jackson was for assuming that the first record was worn and old, the last one, fresh and new; but after examining both tapes under a glass, and seeing how equally clear cut and sharp the impressions all were, they agreed that the extraordinary voice they had heard was practically true to life.

They tried out the rest of the records in that batch, finding that they were all by the same speaker. Nowhere among the ribbons brought from the library was another of his making, although a great number of different voices was included. Neither was there another talker with the volume, the resonance, the absolute power of conviction of this unknown colossus.

This is not place to describe the laborious process of interpreting these documents, records of a past which was gone before earth's mankind had even begun. The work involved the study of countless photos, covering everything from inscriptions to parts of machinery, and other details which furnished clue after clue to that superancient language. It was not deciphered, in fact, until several years after the explorers had submitted their find to the world's foremost lexicographers, antiquarians and paleontologists. Even today some of it is disputed.

But right here is, most emphatically, the place to insert the tale told by that unparalleled voice. And incredible though it may seem, as judged by the standards of the peoples of this earth, the account is fairly proved by the facts uncovered by the expedition. It would be only begging the question to doubt the genuineness of the thing. And if, understanding the language, one were to hear the original as it fell, word for word from the iron mouth of Strokor the Great (in the Mercurian language, strok means iron, or heart)— hearing that, one would believe; none could doubt, nor would.

And so it does not do him justice to set it down in ordinary print. One must imagine the story being related by Strokor himself; must conceive of each word falling like the blow of a mammoth sledge. The tale was not told—it was bellowed; and this is how it ran:

Part II

The Story

CHAPTER I

THE MAN

I AM Strokor, son of Strok, the armorer. I am Strokor, a maker of tools of war; Strokor, the mightiest man in the world; Strokor, whose wisdom outwitted the hordes of Klow; Strokor, who has never feared, and never failed. Let him who dares, dispute it. I—I am Strokor!

In my youth I was, as now, the marvel of all who saw. I was ever robust and daring, and naught but much older, bigger lads could outdo me. I balked at nothing, be it a game or a battle; it was, and forever shall be, my chief delight to best all others.

'Twas from my mother that I gained my huge frame and sound heart. In truth, I am very like her, now that I think upon it. She, too, was indomitable in battle, and famed for her liking for strife. No doubt 'twas her stalwart figure that caught my father's fancy.

Aye, my mother was a very likely woman, but she boasted no brains. "I need no cunning," I remember she said. She was a grand woman, slow to anger and a match for many a good pair of men. Often, as a lad, have I carried the marks of her punishment for the most of a year.

And thus it seems that I owe my head to my father. He was a marvelously clever man, dexterous with hand and brain alike. Moreover, he was no weakling. Perchance I should credit him with some of my agility, for he was famed as a gymnast, though not a powerful one. 'Twas he who taught me how to disable my enemy with a mere clutch of the neck at a certain spot.

But Strok, the armorer, was feared most because of his brain, and his knack of using his mind to the undoing of others. And he taught me all that he knew; taught me all that he had learned in a lifetime of fighting for the emperor. Of mending the complicated machines in the armory, of contact with the chemists who wrought the secret alloy, and the chiefs who led the army.

When I became a man he abruptly ended his teaching. I think he saw that I was become as dexterous as he with the tools of the craft, and he feared lest I know more than he. Well he might; the day I realized this I laughed long and loud. And from that time forth he taught me, not because he chose to, but because I bent a chisel in my bare hands, before his eyes, and told him his place.

Many times he strove to trick me, and more than once he all but caught me in some trap. He was a crafty man, and relied not upon brawn, but upon wits. Yet I was ever on the watch, and I but learned the more from him.

"Ye are very kind," I mocked him one morning. When I had taken my seat a huge weight had dropped from above and crushed my stool to splinters, much as it would have crushed my skull had I not leaped instantly aside. "Ye are kinder than most fathers, who teach their sons nothing at all."

He foamed at his mouth in his rage and discomfiture. "Insolent whelp!" he snarled. "Thou art quick as a cat on thy feet!"

But I was not to be appeased by words. I smote him on the chest with my bare hand, so that he fell on the far side of the room.

The time came when I saw that my father was reconciled to his master. I saw that he genuinely admitted my prowess; and where he formerly envied me, he now took great pride in all I accomplished, and claimed that it was but his own brains acting through my body.

I must admit, too, that I owe a great deal to that gray-beard, Maka, the star-gazer.

I MET Maka on the very morn that I first laid eyes on the girl, Ave.

I was returning from the northland at the time. A rumor had come down to Vlama that one of the people in the snow country had seen a lone specimen of the mulikka. Now these were but a myth. No man living remembers when the carvings on the House of Learning were made, and all the wise men say that it hath been ages since any being other than man roamed the world. Yet, I was young. I determined to search for the thing anyhow; and 'twas only after wasting many days in the snow that I cursed my luck, and turned back.

I was afoot, for the going was too rough for my chariot. I had not yet quit the wilderness before, from a height, I spied a group of people ascending from the valley. Knowing not whether they be friends or foes, I hid beside the path up which they must come; for I was weary and wanting no strife.

Yet I became alert enough when the three—they were two ditch-tenders, one old, one young, and a girl—came within earshot. For they were quarreling. It seemed that the young man, who was plainly eager to gain the girl, had fouled in a try to force her favor. The older man chided him hotly.

And just when they came opposite my rock, the younger man, whose passion had got the better of him, suddenly tripped the older, so that he fell upon the ledge and would have fallen to his death on the rocks below had not the girl, crying out in her terror, leaped forward and caught his hand.

At once the ditch-tender took the lass about the waist, and strove to pull her away. For a moment she held fast, and in that moment I, Strokor, stood forth from behind the rock.

Now, be it known that I am no champion of weaklings. I was but angered that the ditch-tender should have done the trick so clumsily, and upon an old man, at that. I cared not for the gray beard, nor what became of the chit. I clapped the trickster upon the shoulder and spun him about.

"Ye clumsy coward!" I jeered. "Have ye had no practice that ye should trip the old one no better than that?"

"Who are ye?" he stuttered, like the coward he was. I laughed and helped the chit drag Maka—for it was he—up to safety.

"I am a far better man than ye," I said, not caring to give my name. "And I can show ye how the thing should be done. Come; at me, if ye are a man!"

At that he dashed upon me; and such was his fear of ridicule—for the girl was laughing him to scorn now—he put up a fair, stiff fight. But I forgot my weariness when he foully clotted me on the head with a stone. I drove at him with all the speed and suddenness my father had taught me, caught the fellow by the ankle, and brought him down atop me.

The rest was easy. I bent my knee under his middle, and tossed him high. In a flash I was upon my feet, and caught him from behind. And in another second I had rushed him to the cliff, and when he turned to save himself, I tripped him as neatly as father himself could have done it. So that the fellow will guard the ditch no more, save in the caverns of Hofe.

I laughed and picked up my pack. My head hurt a bit from the fellow's blow, but a little water would do for that. I started to go.

"Ye are a brave man!" cried the girl. I turned carelessly, and then, quite for the first time, I had a real look at her.

She was in no way like any woman I had seen. All of them had been much like the men; brawny and close-knit, as well fitted for their work as are men for war. But this chit was all but slender; not skinny, but prettily rounded out, and soft like. I cannot say that I admired her at first glance; she seemed fit only to look at, not to live. I was minded of some of the ancient carvings, which show delicate, lightly built animals that have long since been killed off; graceful trifles that rested the eye.

As for the old man: "Aye, thou art brave, and wondrous strong, my lad," said he, still a bit shaky from his close call. I was pleased with the acknowledgment, and turned back.

"It was nothing," I told them; and I recounted some of my exploits, notably one in which I routed a raiding party of men from Klow, six in all, carrying in two alive on my shoulders. "I am the son of Strok, the armorer."

"Ye are Strokor!" marveled the girl, staring at me as though I were a god. Then she threw back her head and stepped close.

"I am Ave. This is Maka; he is my uncle, but best known as a stargazer. My father was Durok, the engine-maker."

"Durok?" I knew him well. My father had said that he was quite as brainy as himself. "He was a fine man, Ave."

"Aye," said she proudly. She stepped closer; I could not but see how like him she was, though a woman. And next second she laid a hand on my arm.

"I am yet a free woman, Strokor. Hast thou picked thy mate?" And her cheeks flamed.

Now, 'twas not my first experience of the kind. Many women had looked like that at me before. But I had always been a man's man, and had ever heeded my father's warning to have naught whatever to do with women. "They are the worst trick of all," he told me; and I had never forgot. Belike I owe much of my power to just this.

But Ave had acted too quickly for me to get away. I laughed again, and shook her off.

"I will have naught to do with ye," I told her, civilly enough. "When I am ready to take a woman, I shall take her; not before."

At that the blood left her face; she stood very straight, and her eyes flashed dangerously. Were she a man I should have stood on my guard. But she made no move; only the softness in her eyes gave way to such a savage look that I was filled with amaze.

And thus I left them; the old man calling down the blessing of Jon upon me for having saved his life, and the chit glaring after me as though no curses would suffice.

A right queer matter, I thought at the time. I guessed not what would come of it; not then.

CHAPTER II

THE VISION

'TWAS a fortnight later, more or less, when next I saw Maka. I was lumbering along in my chariot, feeling most uncomfortable under the eyes of my friends; for one foot of my machine had a loose link, and 'twas flapping absurdly. And I liked it none too well when Maka stopped his own rattletrap in front of mine, and came running to my window. Next moment I forgot his impertinence. "Strokor," he whispered, his face alive with excitement, "thou art a brave lad, and didst save my life. Now, know you that a party of the men of Klow have secreted themselves under the stairway behind the emperor's throne. They have killed the guards, and will of a certainty kill the emperor, too!"

"'Twould serve the dolt right," I replied, for I really cared but little. "But why have ye come to me, old man? I am but a lieutenant in the armory; I am not the captain of the palace guard."

"Because," he answered, gazing at me very pleasingly, "thou couldest dispose of the whole party single handed—there are but four—and gain much glory for thyself."

"By Jon!" I swore, vastly delighted; and without stopping to ask Maka whence he had got his knowledge, I went at once to the spot. However, when I got back, I sought the star-gazer. I ought to mention that I had no trouble with the louts, and that the emperor himself saw me finishing of the last of them. I sought the star-gazer and demanded how he had known.

"Hast ever heard of Edam?" he inquired in return.

"Edam?" I had not; the name was strange to me. "Who is he?"

"A man as young as thyself, but a mere stripling," quoth Maka. "He was a pupil of mine when I taught in the House of Learning. Of late he has turned to prophecy; and it is fair remarkable how well the lad doth guess. At all events, 'twas he, Strokor, who told me of the plot. He saw it in a dream."

"Then Edam must yet be in Vlama," said I, "if he were able to tell ye. Canst bring him to me? I would know him."

And so it came about that, on the eve of that same day, Maka brought Edam to my house. I remember it well; for 'twas the same day that the emperor, in gratitude of my little service in the anteroom, had relieved me from my post in the armory and made me captain of the palace guard. I was thus become the youngest captain, also the biggest and strongest; and, as will soon appear, by far the longest-headed.

I was in high good humor, and had decided to celebrate with a feast. So when my two callers arrived, I sat them down before a magnificent meal.

Edam was a slightly built lad, not at all the sturdy man that I am, but of less than half the weight. His head, too, was unlike mine. His forehead was wide as well as tall, and his eyes were mild as a slave's.

"Ye are very young to be a prophet," I said to him, after we were filled, and the slaves had cleared away our litter. "Tell me, hast foretold anything else that has come to pass?"

"Aye," he replied, not at all boldly, but what some call modestly. "I prophesied the armistice which now stands between our empire and Klow's."

"Is this true?" I demanded of Maka. The old man bowed his head gravely and looked upon the young man with far more respect than I felt. He added:

"Tell Strokor the dream thou hadst two nights ago, Edam. It were a right strange thing, whether true or not."

The stripling shifted his weight on his stool, and moved the bowl closer. Then he thrust his pipe deep into it, and let the liquid flow slowly out his nostrils. (A curious custom among the Mercurians, who had no tobacco. There is no other way to explain some of the carvings. Doubtless the liquid was sweet-smelling, and perhaps slightly narcotic.)

"I saw this," he began, "immediately before rising, and after a very light supper; so I know that it was a vision from Jon, and not of my own making.

"I was standing upon the summit of a mountain, and gazing down upon a very large, fertile valley. It was heavily wooded, dark green and inviting. But what first drew my attention was a great number of animals moving about in the air. They were passing strange affairs, some large, some small, variously colored, and they were all covered with the same sort of fur, quite unlike any hair I have ever seen."

"In the air?" I echoed, recovering from my astonishment. Then I laughed mightily. "Man, ye must be crazy! There is no animal can live in the air! Ye must mean in the water or on land."

"Nay," interposed the stargazer. "Thou hast never studied the stars, Strokor, or thou wouldst know that there be a number of them which, through the enlarging tube, show themselves to be round worlds, like unto our own.

"And it doth further appear that these other worlds also have air like this we breathe, and, that some have less, while others have even more. From what Edam has told me," finished the old man, "I judge that his vision took place on Jeos (the Mercurian word for earth), a world much larger than ours, according to my calculations, and doubtless having enough air to permit very light creatures to move about in it."

"Go on," said I to Edam, good humoredly. "I be ever willing to believe anything strange when my stomach is full."

THE dreamer had taken no offense. He went on, "Then I bent my gaze closer as I am always able, in visions. And I saw the greenery was most remarkably dense, tangled and luxuriant to a degree not ever seen here. And moving about in it was the most extraordinary collection of beings that I have ever laid these-eyes upon.

"There were some huge creatures, quite as tall as thy house, Strokor, with legs as big around as that huge chest of thine. They had tails, as had our ancient mulikka, save that these were terrific things, as long and as big as the trunk of a large tree. I know not their names. (Probably the dinosaur.)

"But nowhere was there a sign of a man. True, there was one hairy, grotesque creature which hung by its hands and feet from the tree-tops, very like thee in some way, Strokor. But its face and head were those of a brainless beast, not of a man. Nowhere was there a creature like me or thee.

"And the most curious thing was this: Although there were ten times as many of these creatures, big and little, to the same space as on our world, yet there was no great amount of strife. In truth, there is far more combat and destruction among we men than among the beasts.

"And," he spoke almost earnestly, as though he would not care to be disbelieved, "I saw fathers fight to protect their young!"

I near fell from my stool in my amaze. Never in all my life had I heard a thing so far from the fact; "What!" I shouted. "Ye sit there like a sane man, and tell me ye saw fathers fight for their young?"

He nodded his head, still very gravely.

"Faugh!" I spat upon the ground. "Such softness makes me ill! I'll be glad I were born in a man's world, where I can take a man's chances. I want no favoring. If I am strong enough to live, I live; if not, I die. What more can I ask?"

"Aye, my lad!" said Maka approvingly. "This be a world for the strong. There is no room here for others; there is scarce enough food for those who, thanks to their strength, do survive." He slipped the gold band from off his wrist, and held it up for Jon to see. "Here, Strokor, a pledge! A pledge to—the survival of the fittest!"

"A neat, neat wording!" I roared, as I took the pledge with him. Then we both stopped short. Edam had not joined us.

"Edam, my lad," spake the old man, "ye will take the pledge with us?"

"I have no quarrel with either of ye." Edam got to his feet, and started to the door. "But I cannot take the pledge with ye.

"I have seen a wondrous thing, and I love it. And, though I know not why, I feel that Jon has willed it for Jeos to see a new race of men, a race even better than ours."

I leaped to my feet. "Better than ours! Mean ye to say, stripling, that there can be a better man than Strokor?"

I fully expected him to shrink from me in fear; I was able to crush him with one blow. But he stood his ground; nay, stepped forward and laid a hand easily upon my shoulder.

"Strokor—ye are more than a man; ye are two men in one. There is no finer—I say it fair. And yet, I doubt not that there can be, and will be, a better!"

And with that such a curious expression came into his face, such a glow of some strange kind of warmth, that I let my hand drop and suffered him to depart in peace. Such was my wonder.

Besides, any miserable lout could have destroyed the lad.

Maka sat deep in thought for a time, and when he did speak he made no mention of the lad who had just quit us. Instead, he looked me over, long and earnestly, and at the end he shook his head sorrowfully and sighed:

"Thou art the sort of a son I would have had, Strokor, given the wits of thy father to hold a woman like thy mother. And thou didst save my life."

He mused a little longer, then roused himself and spake sharply:

"Strokor, thou hast everything needful to tickle thy vanity. Thou hast the envy of those who note thy strength, the praise of them who love thy courage, and the respect of they who value thy brains. All these thou hast, and yet ye have not that which is best!"

I thought swiftly and turned on him with a frown: "Mean ye that I am not handsome enough?"

"Nay, Strokor," quoth the stargazer. "There be none handsomer in this world, no matter what the standard on any other, such as Edam's Jeos.

"It is not that. It is, that thou hast no ambition."

I considered this deeply. At first thought it was not true; had I not always made it a point to best my opponent? From' my youth it had been ever my custom to succeed where bigger bodies and older minds had failed. Was not this ambition?

But before I disputed the point with Maka, I saw what he meant. I had no final ambition, no ultimate goal for which to strive. I had been content from year to year to outdo each rival as he came before me. And now, with mind and body alike in the pink of condition, I was come to the place where none durst stand before me.

"Ye are right, Maka," I admitted. Not because I cared to gratify his conceit, but because it were always for my own good to own up when wrong, that I might learn the better. "Ye are right; I need to decide upon a life-purpose. What have ye thought?"

The old man was greatly pleased. "Our talk with Edam brought it all before me. Know you, Strokor, that the survival of the fittest is a rule which governs man as well as men. It applies to the entire population, Strokor, just as truly as to me or thee.

"In fine, we men who are now the sole inhabitants of this world, are descended from a race of people who survived solely because they were fitter than the mulikka, fitter than the reptiles, the fittest, by far, of all the creatures.

"That being the case, it is plain that in time either our empire, or that of Klow's, must triumph over the other. And that which remains shall be the fittest!"

"Hold!" I cried. "Why cannot matters remain just as they now are?"

"That," he said rapidly, "is because thou knowest so little about the future of this world. It is now known that the sun is a very powerful magnet, and that he is constantly pulling upon our world and bringing it nearer and nearer to himself. That is why it hath become slightly warmer during the past hundred years; the records show it plain. And the same influence has caused the lengthening of our day."

He stopped and let me think. Soon I saw it clearly enough; a time must come when the increasing warmth of the sun would stifle all forms of vegetable life, and that would mean the choking of mankind. It might take untold centuries. Yet, plainly enough, the world must some day become too small for even those who now remained upon it.

Suddenly I leaped to my feet and strode the room in my excitement. "Ye are right, Maka!" I shouted, thoroughly aroused. "There cannot always be the two empires. In time one or the other must prevail; Jon has willed it. And"—I stopped short and stared at him—"I need not tell ye which it shall be!"

"I knew thou wouldst see the light, Strokor! Thou hast thy father's brains."

I sat me down, but instantly leaped up again, such was my enthusiasm. "Maka," I cried, "our emperor is not the man for the place! It is true that he was a brave warrior in his youth; he won the throne fairly. And we have suffered him to keep it because he is a wise man, and because we have had little trouble with the men of Klow since their defeat two generations gone.

"But he, today, is content to sit at his ease and quote platitudes about 'live and let live.' Faugh! I am ashamed that I should even have given ear to him!"

I stopped short and glared at the old man. "Maka, hark ye well! If it be the will of Jon to decide between Klow and the men of Vlamaland, then it is my intent to hasten this decision!"

"Aye, my lad," he said tranquilly. And then he added, quite as though he knew what my answer must be: "How do ye intend to go about it?"

"Like a man! I, Strokor, shall become the emperor!"

CHAPTER III

THE THRONE

A SMALL storm had come up while Maka and I were talking. Now, as he was about to quit me, the clouds were clearing away and an occasional stroke of lightning came down. One of these, however, hit the ground such a short distance away that both of us could smell the smoke.

My mind was more alive than it had ever been before. "Now, what caused that, Maka? The lightning, I mean; we have it nearly every day, yet I have never thought to question it before."

"It is no mystery, my lad," quoth Maka, dodging into his chariot, so that he was not wet. "I myself have watched the thing from the top of high mountains, where the air is so light that a man can scarce get enough to fill his lungs. And I say unto you that, were it not for what air we have, we should have naught save the lightning. The space about the air is full of it."

He started his engine, then leaned out into the rain and said softly: "Hold fast to what thy father has taught thee, Strokor. Have nothing to do with the women. 'Tis a man's job ahead of thee, and the future of the empire is in thy hands.

"And," as he clattered off, "fill not thy head with wonderings about the lightning."