Help via Ko-Fi

THERE was no space in the tiny cabin for nervous pacing. A scant eight feet separated the hallway entrance from the small porthole that showed the dull black of space; and across, the distance from the locked door on one side wall to that on the other could have been spanned by the young man's arms. Only his eyes were free to roam the narrow room, and they were tired with endless repetition.

For a moment, his gaze rested idly on the porthole, and he stared outward through the cold and the darkness to the tiny point of light that was Earth; but there was no conscious recognition of what he saw. His eyes dropped back to the shelf that held his manuscript. his ink, and the purple, untouched candle. And it was only as he picked up the lump of wax with slow, reluctant fingers that he thought of the valley in the hell world that had produced it....

THE MAN'S shoulders were bowed under the grim weight on his back, and the alpine stock trembled in his grasp. But he fought upwards over the last remaining feet until he was at the top of the pass, and the wastelands were behind. Even then, he could not trust the weight of his burden to his shaking hands, but sank carefully to a sitting posture until it touched the ground, and he could ease his arms out from the straps. Finding a reasonably portable generator to replace the one they could patch no more had been a miracle, and he had no faith in a second one.

For a time he lay quietly, breathing in ragged gasps and staring into the valley that was cut o? completely from the world by the surrounding mountains, except for this one narrow pass. Dirty snow straggled down to blend with leprous, distorted scrub trees and run down to flat land. And there, a few log and stone buildings stuck up uncertainly among crumbling ruins, to mark the last failing outpost of the human race, three centuries after the Cataclysm. The man grimaced, and began to pull himself to his feet.

Then an answering clatter of stones sounded from around a rock, and Gram was beside him, pulling him upright and massaging his still trembling shoulders with gentle hands. Her seamed old face broke into a brief flicker of perfect teeth, and her fingers were unsteady, but there was no emotionalism in her voice. "I saw your smoke signal last night, so I've been waiting. I guess I must have been catching a catnap, though. You've been gone a long time, Omega. Okay?"

"Okay, Gram. The generator's in there, and enough fluorobulbs to light all the huts. But I'm glad I didn't have to stretch rations another day. I had to work my way clear to old Fairbanks to find it. That wasn't pretty! They knew it was coming hours before the stuff hit them!"

"Umm. Here! I figured you'd be hungry. As for the bulbs—" She shrugged and pointed to the purplish plants that grew all around, a mutation as deadly as the hard radiations that had produced them. "I'll stick to sprayberry-wax candles. They have other uses; at least Peter thought so." So gentle, patient old Peter was dead, and there was only an even dozen of them now! But Omega was too tired to care much about anything except the food Gram held out. She watched him wolf it down, and her face lighted faintly as she dropped beside him.

"Eleven worn-out old people and you, now. The last dozen poor supermen," she said with a nod toward the valley; and her voice was filled with the same grim humor that had made her christen him Omega when his mother committed suicide over the rock-mangled body of his father.

But Omega knew it was more than humor. In a normal world, with a decent background and half a chance, they might almost have passed for supermen; except that no such world could have produced them! That had required an Earth left wrecked by the Cataclysm from a cold and casually unjust universe—a world where hard radiations made every birth a mutation and where every undesirable change was savagely purged from the race.

IN A WAY, it was ironic that men had barely avoided wrecking the planet themselves with plutonium, the lithium chain reaction, or the final discovery of a modified solar-phoenix bomb. But somehow they had eliminated that danger at last, and found their triumph useless.

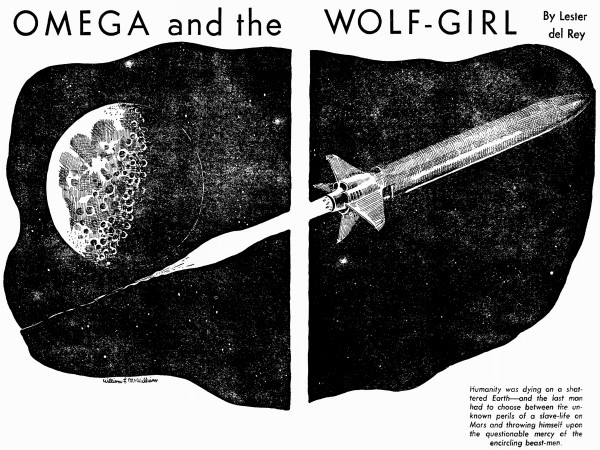

It had been a simple communique from the new Lunar Observatory, at first; they had spotted a meteor having a paradoxically weak but impossibly hot level of radiation that indicated contra-terrene, or "inside-out" matter. The second announcement spoke guardedily of the danger of grazing contact. And fifteen minutes later, the moon ripped apart as electrons cancelled out positrons into energy, and left a great flood of unattached and destructive neutrons.

Surprisingly, there were survivors of the rain of hell-fragments that fell to the earth. Near the poles, a few deep and narrow valleys were only grazed slightly, and where three contained mines or caverns to offer some protection against the radioactive dust that fell everywhere, a measure of life went on after a fashion, and a thousand or so survived. Now three centuries had whittled down the number, and wild mutations and a ruthless survival of the fit had compressed a thousand generations of evolution into one.

There was Gram, who might have saved the race, if her cell structure had appeared in time. Like the wolves and the rabbits that had inherited the earth, her cells had finally found the mutation of totipotency that defied all but the most intense concentration of radiation to burn them or cause further mutations. When a wild new plague had wiped out her people in another valley, she had taken the boy who was to become Omega's father, a rifle, and a sled, and set out through a roaring blizzard to cross four hundred miles of hell to this place. Now, sixty years later, she could still outwork any man in the valley, except for Omega's maternal uncle, Adam, on the rare occasions when he exerted himself.

For Adam had specialized in pure laziness and purer logic that seemed to leap from isolated hints of facts to full-blown knowledge without effort. He had slouched in when Omega was fumbling over calculus, and his eyes had lighted with sudden interest in the books he had never troubled to read. Hours later, he had been explaining and making clear the complex mathematics which his mind had carried beyond the wildest dreams of the pre-chaos scientists. But it required more than such wild talents to separate a group of freaks from supermen; it took background, opportunity, racial culture, and a future. And in those things, the wolves were their superiors.

SUDDEN light flashed up from the valley, disappeared, and returned to hover beside them. Then the spot wobbled erratically across the pass and came to rest against a flat, shaded rock, danced crazily, and steadied down to business. Below, the thin, lanky hands of old Eli must have been using the big mirror on a long board to give the microscopic leverage that was all he needed. His talent lay in a coordination and control of nerves and muscles so nearly perfect that he could shape and handle the infinitesimal tools needed to manipulate individual microorganisms within the field of a microscope. Now the spot of light fluttered, but its motions were clear enough to spell out letters.

"Hurry, need generator," Gram read, and chuckled. "Sure you found one, eh? Let them-uh!—Wolf—girl—located!"

A gamut of expressions washed over her face, giving place to sudden determination. "Come on, Omega! You can rest later. Here, let me help you with that pack!"

"Why the hurry, and what's all this wolf-girl stuff about?" After the short rest, the pack weighed a ton, and the pass looked ten miles long. No wolf was that important, whatever it had done.

Gram slowed up a little. "Something we never meant to bother you with—Ellen's baby—your cousin. Grown up now, must be. We saw her with a wolf pack once before when you were away, but thought she'd died later. Oh, come on, before they start a search without shields. I'll tell you some other time."

"They won't start without shields," he assured her. "She was living with wolves, Gram?"

"Must have been. And they'd start, all right. Tom and Ed died out there last time before you invented shields! When it comes to race preservation, they'd all rather burn than see you go unmated! Will you hurry?"

He hurried; nobody disobeyed Gram. But there was a picture of what a wolf-girl would be in his mind, and the idea of such a mating sat heavier on him than the pack. And he'd thought the old fires of racial preservation were dead!

Adam met 'them, took the pack, kicked aside one of the shaggy, huge-cared pigs, and paced beside Gram without a trace-of laziness. Its squeals gave the boy time to get over the shock of that before his uncle answered Gram's questions.

"Jenkins—off by himself as usual—went to sleep at the far end. Early morning a howling woke him, and there she was with a couple of wolves. He got a good look—human all right, stick in her hand. Time he got there, she was gone, but he saw the direction; reckon I know where she lairs. Came in half an hour ago, fagged out. Soon as he told us, we signaled."

"Umm. Wonder where she's been since we saw her the other time, Adam?"

"Off somewhere. Studied wolves when I was a kid—they wander all over. And with your blood, so could she. Lucky she's back." They reached the powerhouse, and Adam shut up, while Eli began bolting down the generator on a rough base and connecting it to the old water wheel. There was a glow on his face that was new to Omega, and it was reflected by the faces of the rest of the group.

THEY were all there, except for Jenkins, whose green pigmentation and chromosomes that came in triplets instead of pairs represented the only remaining physical abnormality. With that had gone a whole host of wild extrasensory talents that made him fully aware of the unpopularity they won him. Of the others, Eli, Adam, and Simon were already harnessed into the shields. A product of Adam's mathematics, Eli's amazing workmanship, and some of Omega's ideas, they made space a nonconductor of all radiation beyond a certain energy level. They also distorted gravity slightly for some reason, but it was the only way the others could travel in the outlands.

Simon snapped the last battery in place as it finished flash-charging, while Gram made a hasty inspection. "Omega's worn out, and I don't want her to remember me as the one who caught her, if I'm to handle her, so it's up to you. Think you can do it, Adam?"

"I figured some on it. We'll get her."

"Good." She watched them start, and turned back to her hut. "Let the others gaup, Omega, but we're eating, and then you're going to bed... after I tell you about Ellen and the girl."

It wasn't much of a story. Besides Omega's father, Gram's hitherto unmentioned baby daughter had survived the plague and the trip. She'd grown up, married Simon after Omega was born, and there'd been a baby coming. Jenkins, who would know, had said that he could tell it was to be a girl.

But some accident on the hellish march had twisted Ellen's mind, and she grew up as an insanely religious fanatic. Apparently the thought of her baby marrying a cousin had been a heinous sin in her eyes. Anyway, they found a wild note, but they had never been able to trace her despite their searches.

"God knows, we tried." Gram's soup was untouched before her. "You never spent years praying for just one girl-child—one fertile girl in a world dying of sterility, Omega! Just one, because the hard rays couldn't trap your kind from the world anymore. My line's fertile, and the baby would have been.... You're too young to understand, but the old need babies; when you're close to death, you need proof that you're physically immortal through the race—not just soul-stuff. Oblivion's close and taut around you when there's nobody left to remember.... Oh, go to bed before I start blubbering!"

"Can they catch her alive?" he asked as Gram began drawing the pig's-wool blankets up over him.

"They'll do it, somehow; we made an agreement to that. Either they come back with her alive, or they rot out there!"

She closed the door quietly behind her, and Omega was alone to wonder at the savage drive that had lain dormant and unknown so long around him. But no thoughts could keep a man awake after the grueling trek he'd just finished, and somewhere in the middle of the thought, he blanked out.

THE SEARCHERS were already in sight when Gram awakened him, two of them staggering under the twisting gravity inside the shields; but Adam apparently was able to predict the shifting force, and the leading figure was steady and resolute. Between the others, there was a covered figure on a long pole, and the tiny clan was gathered outside the but in a shouting group. But by the time Omega had doused his head in water and joined them, they were silent again. The three were closer now, and their faces and the pose of their bodies could be seen, even in the gathering twilight.

They dropped their burden in the same rigid silence, and Simon, who had been Ellen's mate and father to the child, turned, motioned to his twin sister, and went off toward their hut. The others waited uncertainly. until Adam bent down to pull the blanket from the figure on the ground. "Wrong word accented on wolf-girl, Gram, but here she is. Now what?" And he yanked the cover from the forlorn creature that lay bound by its feet to the pole.

It was a wolf; strange and odd of form though she was, there could be no shadow of doubt as to her lupine origin. The teeth that gleamed through the ropes around her jaws were wolf fangs, and the tail settled any further question.

Yet it was easy to see how Jenkins could have thought her a woman in the dim starlight, for the mutation that had somehow produced her in spite of her parental totipotency had shaped her into a mockery of human form, and she was as anthropoid as wolfish. Her rear legs were long, and her short front ones ended in lengthened toes to caricature human hands. Her forehead bulged, and her jaw was foreshortened, while the mane on her neck might have been mistaken for a head of hair if she stood upright. And because she was built in a woman's shape, there was something pitiful about her as she lay glaring up at them.

Jenkins felt it first, and his sigh broke their silence; he pushed forward, his shy, fearful eyes half-filled with tears. For a second, he hesitated, before his hands ripped aside the cords that bound her mouth. Her lips drew back, but she made no move to snap at him as he faced the others, his quavering, timid voice filled with bitterness and apology.

"The ropes cut her lips, Gram. Her mind's all dark and swirling fog, hard to see, but she's crying. Not for herself, but for her babies back there, little ones like her. Do we have to kill her, Gram?"

Gram shook her head to clear it, and her voice was as low as his, and as uncertain. "But you saw the wolf-girl carrying a stick. Can we be sure...? Look further into her mind."

"We found the stick," Adam answered for him. "She'd need one, with her build. Couldn't run on all fours, not quite ready to go upright very long. Jenkins, what's her name?"

"Her name? I—I can't see very well. Something about hunger—pain, I think."

"Bad-Luck. Called that because of the way she's built, I guess. Not much of a language. unless they changed it since I was a kid. Better'n your telepathy, though. You read off what I think, while I try her."

HIS LIPS contorted out of shape. and a queer, wailing whine slid eerily out. The wolf-girl's head jerked around, and her eyes shot behind him, to come back reluctantly to his as he called again. At the third try, her own lips parted in an effort, closed, and opened in sounds between a growl and a whine, yet somehow articulated and hopeless. Perhaps the sight of a man and a wolf-mutation talking was as logical an ending for the day as any other; at least, the little audience watched in unchanging dull listlessness.

Jenkins' voice droned forth, reading the meaning from Adam's mind. "Surprised at him... not mad at us, why should she be... hunting's natural.... Is he man or wolf?... Yes, she'll answer his questions. No, never saw any human shes outside the valley... no baby shes.... When are we going to eat her?"

"Ugh! I suppose.... Oh, let her go! I wish I'd never known she could talk, Adam, but now—" Gram sighed, staring about for suggestions and finding none. "Tell her we'll feed her, since we ruined her hunting, and let her go; but she's to keep out of our valley and let our stock alone. I guess that's all we can do now. Can you tell her that in her language?"

"Say it all right—they've improved it some; but for her to understand's another thing. Translate the Bible to wolfish, if I had to, but it wouldn't mean much to her. Takes semantic training to work out much with a hundred odd words, though it can be done. Umm!" He frowned, considering, and little Jenkins, again conscious that his gifts were unwelcome among normal minds, slipped away quietly before Adam began.

It took longer this time, and there could be no doubting the surprise and slow dawn of hope on the creature's face as the meaning finally sank in. She lay quietly, her eyes riveted on his as he untied her; but it wasn't until he placed a frozen leg of pork in her oddly human hands that she believed him. Then she was gone at a jerking run.

But she stopped, hesitantly, as a high wail broke from him, and paused long enough to answer his cries. before her figure faded away into the twilight. He grinned crookedly at Gram, and shrugged. "No smell of people outside that she knows of."

"No." Gram sighed again, and pushed the door open. "Come on inside, Adam, Omega. The rest of you go back to your huts. There's no good to be had from freezing out here. We had our fun, but it's over now. and we can forget the wolf-girl idea."

In that, she was wrong. It was less than three hours later when a subdued howl from outside drew Adam up from the table and out into the night. Outlined in the dim light of the open door, Bad-Luck had returned, and beside her hovered an old and grizzled wolf, with raised hackles and bared fangs, but motionless as the feared man-beast approached.

Their conversation was erratic and uncertain, with long silences, but eventually Adam nodded, and the wolves melted into the darkness. He came back to the hut with a shake of his head and a strange smile, and dropped onto the stool to watch Grants hands go on remorselessly with her Canfield.

"The old wolf is their Far-Food-Sniffer; keeps in touch with all other packs, I gather. Anyhow, no wolf on the whole planet knows the smell of men, except here.... Funny! Nature seems to be cooking up replacements for us, and not wasting time. Came a long way since I studied them. Ethics!"

Gram nodded wearily, and -dead, dull silence settled over the hut, relieved only by the monotonous slap of the cards.

IT WAS barely past noon when Simon and his sister were found the next day, deep in the catalepsy of sprayberry poison. Within them, the incredibly slowed labor of breath and heartbeat would go on for hours longer, but it was too faint to be detected, and their bodies were already cool to the touch. Yet they could still be revived, and Omega turned automatically to get the neutralizing dye. Adam's hand stopped him.

"No use, boy. There's always more poison." He looked around the room once more, taking in the magnificent paintings the twins had done, then pulled the door shut behind them and began nailing boards over it. Wooden steps carried them back to the cold-frames where Gram and Eli were at work setting cabbage seedlings. But the hammering had carried the news before them, and no comments were made.

The only sound was a distant drone, like an early swarm of bees, and it disappeared as Omega dropped to the cold earth, and began replanting. How many, he wondered, would live to eat the plants when they were grown? There were only ten now!

Then the buzzing was back, and Gram was dragging the others up to face the sky, where a roaring something grew out of emptiness, flashed over, and faded away again. "A ship! A jet plane!"

It couldn't have been, and yet it was. There was no habitable land below 60° South Latitude; one colony of the original three had reported itself dying of famine; Gram's had perished in the plague; and the wolves knew of no smell of men outside the valley!

But they were already at the powerhouse, and Eli's hands flipped over the switches of the crude spark-gap transmitter the first survivors had built, and the current danced between the electrodes in code so rapid it was like a steady crackle. He waited futilely for an answer from the humming speaker, and began transmitting again.

Then the roar was back, and they had only time to look out before a flash of metal screamed down, wriggled, zipped up across the pass, and was gone again. Gram lifted her fist. "The dirty spalpeens! Making fun—"

Before she could complete the gesture, a young masculine voice but-bled out of the speaker. "Hi, people! Took a little time to find and match your frequency—your signal sprays all over the kilocycles. I can't understand that greased lightning c. w., though. so give me three slow dots if you can receive modulated stuff.... Fine! Sorry I couldn't land with my fuel reserves, but I'll be back. Meantime, take a look at the film I dropped. Planet Mars, signing off!"

Mars! They'd been almost ready for that, but.... And the voice had been filled with a strange quality that instinct recognized as youthful enthusiasms and sure self-confidence. It must be nice-

Jenkins interrupted their reverie by laying a package on the bench. That would be the film, though he alone had seen it fall. For the first time any of them could remember, Eli's hands fumbled as he ripped at the junk wound hastily around the thing, and it was Adam who finally freed the little machine and found the light switch. He focused it carefully against the gray stone wall, located another but-ton, and sat back to watch the moving scenes.

They were obviously conventionalized drawings, at first, but they were clear enough. A man labelled Mason stood in the port of a crude rocket ship with his young wife, while a crowd cheered and drew back. They waved, shut the port, and lifted on a jet of flames.

The Earth shrank behind, while the moon slid into view and went quickly past. But Mason was framed in a porthole, just as the moon broke loose in lancing hellfire. Scenes showed his wife trying to nurse his burned body. and frantically fighting to bring the ship down on Mars in a crumpled landing. And then, furry, four-armed anthropoid things came out to take Mason and his wife down to a strange underground and primitive world.

After that, Mason was their teacher. They had been dying for lack of power, but now the ships' atomotors gave them the margin they needed to rush upwards to a self-sustaining civilization that could even bake air and water out of the dead crust of the planet.

Mason grew older, and six girls were born to him. But careful schematics showed that the moon-blast had rendered his male sperm cells sterile, and there were no boys. They stored his superfrozen spermatozoa and sought valiantly for a cure, but they had not succeeded when the screen portrayed his funeral procession.

The final scene showed a glorified statue of Mason, holding a book in one hand and stretching a symbolic atom upwards with the other. Below, eight young and human women were grouped about a great rocket, with their faces turned to the sky and their arms lifted in mute appeal. Then the film ended.

OMEGA wasted no time on the others' comments. The boards on Simon's door came ripping off under his straining muscles, and he was inside and forcing black liquid down the throats of the twins. The vegetable dye they used to color their clothes and serve as their writing ink had revived poisoned pigs before and should serve equally well for men. It did. The late afternoon sun saw twelve of them again, watching as the ship settled downward on its jets a hundred yards away.

A thin, four-armed, furry figure came out, to be followed by two apparently identical others. And then, while the dozen waited in tense expectancy, the door closed firmly and they headed toward the group—three Martians and no Earthmen! Beside him, Omega heard Gram's breath whistle out heavily, and an animal snarl from Jenkins. Only Adam seem unruffled and unsurprised as he sauntered forward to grasp their leader's hand and make proper introductions.

Jaluir's furry face remained expressionless, but his voice was the warmly enthusiastic one that had come over the speaker. "So you really do exist? Where the deuce were you last winter? There wasn't a sign of life that we could see."

"Holed up. Snow gets twenty feet deep down here—covers everything. We seal up and hibernate in the caverns back there till after the spring floods. Explore all nonradioactive areas?"

"All seventeen. This one came last, and our plane broke down for a month, or we'd probably have found you." He shrugged, a gesture that must have come down from Mason. "After that, we gave up hope until I made a forced landing in old Fairbanks. I was pretty sure someone had been there recently, and Commander Hroth let us stay over another week. But it was a devil of a job locating your campfire sites to get a fix."

"Why bother? You didn't come just to see us—not with people of our kind on Mars!" Gram's voice was suddenly old, tired, and suspicious, and the Martian blinked in surprise.

"We needed some metals, of course —but we wouldn't have crossed space yet for just that." He hesitated, and his next words were fumbling and uncertain. "The girls who saw us off—we failed, in spite of them—they are the last. We had only the Prophet's male germs.... We have taboos, too, ma'am, but—well, we had to do what we could. Now, when our hopes were gone, the gods have given us life again!"

"Urnm. Well, you might mean it. You and your friends had better come inside. No use standing out here."

"If it's all the same, I'd rather see that radio transmitter of yours," he answered.

GRAM nodded grudging approval, and Omega was glad of the excuse to rescue him from their frozen faces. It didn't make sense. When even a Martian crossed forty million miles to pay a neighborly visit, he deserved a little warmth in his reception. Instead, Gram was adopting the same attitude with which she'd greeted Adam's proposal to scrap English and switch to a fully semantic language of his devising. The boy fell into step with the alien, while the others followed.

The transmitter held Jaluir's attention for only a minute before his eyes began traveling over the rest of the powerhouse. The crude Millikan microscope Adam had designed from the fruits of Omega's wanderings was inspected more thoroughly, to be followed by one of the little radiation shields.

"Cuts off high energy radiation," Adam volunteered, and his eyes were speculative, in spite of his easy grin. "Take it along if you can use it."

The Martian nodded and dropped it into a pouch on his belt—his only article of clothing. "Simple after someone else discovers the principle. Thanks! We certainly can use it.... We wondered how you reached Fairbanks!"

Gram grunted. "Nonsense! Omega and I don't need contraptions; we're naturally immune to radiations!"

"Zot luill! You're—!" The face that he turned to the boy now was no longer expressionless. It held a burning excitement that no alienness could conceal. He twisted on his heel and snapped out syllables in a strange tongue that sent the other two Martians toward their ship in a clumsy run. But when he faced them again, his emotions were under control, and his voice was quite even and friendly.

"Sorry, but I've got to go back to the ship for a few minutes. Look, let's get down to brass tacks, shall we? How soon can you leave?"

"For Mars?" Gram asked.

"For Mars. It'll be five hundred years before Earth is really habitable again, at least! And you can't go on in these little valleys. What better sanctuary than a grateful Mars? Of course, you'll need a little time—but talk it over until I get back."

And he was gone after his companions.

GRAM sighed wearily, and the stiffness drained out of her body. "Sanctuary—or slave pen? He seemed nice enough, but—"

"He's a monster!" Jenkins' normal meek whisper was distorted into a savage, hate-filled wheeze. "An inhuman monster! His brain is blank—all blank. I can't even feel it."

Adam's cool voice cut into his ravings. "Take it easy! If you can't snoop in his mind, you don't know what he is. And you don't hate a man for that—or do you? Personally, I liked Jaluir."

"So did I," Gram admitted, but there was no lifting of the frown on her face. "We would! You can't catch a wolf without something attractive for bait. And maybe he is all sweetness and light. The missionaries meant to help the Aztecs, until they found gold and Cortes came. And our ancestors made slaves of the black people, and tried to exterminate the Jews for not being exactly like them-selves-and Mars is a lot stranger to us than anything we found here. Maybe we're gods to them, as he says; and maybe we're animals."

Their doubts were growing by a process of mutual induction, until even Omega's-ideas began to veer toward them. But his words carried no conviction in either direction. "Of course, we can't be sure; we have only the evidence they designed for us. But he seemed friendly."

"Why shouldn't he, when our planet's loaded with minerals they need? We're used to gravity that makes them uncomfortable, and we can stand the radiations, now. He liked that part a little too much!"

Gram hesitated, and her gaze turned to the east where her native valley lay. "We always took even better care of our animals than ourselves. I know, because we had horses when I was a girl-until a careless fool left a gate open and our two stallions were killed by wolves. He tried to hide the evidence, because he knew what we'd do to him. But I saw it all, and I was young enough to carry tales. Poor devil! They turned him out to the wolves, eventually.... Men will do strange things for beasts of burden, Omega."

"Or for pets." Adam added thoughtfully. "Vote?"

But no vocal poll was needed. Simon and his sister moved toward the door, and his sad, dulled eyes were quietly reproving as he looked at Omega. Gram turned from one to another, and at last she nodded quietly and went out toward the huts. In a moment, only Adam and Omega were left in the building.

Jaluir found them there, and the lilting jingle on his lips broke off in a sudden puzzled grunt. Adam chuckled wryly. "Gone! Took a vote, after a fashion. It's a lousy world, Jaluir, but we're staying. And don't ask why, because I don't know."

"But you can't—you're.... All of you? Omega too?"

"That's up to him; he didn't vote. Rest of us stay, anyhow.".

"Oh." Jaluir considered it, shrugged, and gave it up as a hopeless riddle. "I won't pretend I can understand, but if that's the way you really want, it, I'll explain it to Commander Hroth somehow. Anyway, I've got to return to the main ship before it gets dark, so I'd better shove off now. But I'll be back in the morning to pick you up, Omega."

He grasped the hand Adam held out and was gone, to take off a minute later in a?aming roar and go speeding over the mountains. Adam slumped against the door for a few seconds, then came in and began quietly buckling on a radiation shield.

"Going up to talk with the wolf-girl," he volunteered with deliberate casualness as he finished. "Curiosity. If I don't get back in time to see you off—"

"Who made up my mind I was going—Jaluir or you?"

"Fate! If they're nice people, you should; if not—well, they'll have weapons and ways. Good luck, son!" He slapped his nephew's back lightly, grinned, and went sauntering off, leaving Omega alone with his thoughts. They were not good company.

But Adam's logic was unanswerable, and Omega's packing was done in the morning when he awoke from fitful slumber to see the plane already landed and waiting beside the row of silent, boarded-up huts. He had helped Gram nail them shut during the night, and he knew that only Gram and he were left, besides Adam, still among the wolves. Even little Jenkins and his queer twisted talents! Gram's eyes, red with lack of sleep, followed his gaze.

"Forget them, boy. Jenkins was always a little crazy, and Eli was dying of cancer, anyhow. The rest were—useless! Sometimes I used to wonder about such things—the warped, strange ideas of isolated little communities, and the references in the psychology books to contagious suicide during times of trouble. But there's something more."

She shook her head wearily, drawing her hand across her forehead. "It's a curse, a will to death that made them Sterile because they wanted to be, and made them die whenever they had an excuse—no matter how much they refused to believe it. Call it a mutation that crept in unnoticed, or say the whole race gave up and went quietly insane after the hell years. They could have built some kind of glider-plane and kept contact between the valleys, if they'd had the spunk, and none of this would have happened. Anyway, there's a curse on the valleys.... You'd better go now, Omega. Don't keep Jaluir waiting too long."

There were words inside him, but they wouldn't come out. Gram laid her brown old hand gently on his mouth, and the ghost of a smile appeared on her lips. "No, just go. And sometime, if you have children—not slave children, Omega, but men—tell them of me. I'd like that!"

The door was closed when he looked hack, and the valley was strange and oppressive. Jaluir motioned him to a seat beside a window away from the huts, and he sat staring at the instrument board for what seemed hours while the plane waited. Then the jets screamed out, and they were airborne after a brief run.

"Below," the Martian said softly, and pointed.

TINY but distinct against a patch of snow, a figure stood waving up at them surrounded by dark dots that must have been the wolves. Jaluir dropped the plane and circled as close as he could, and for a moment Adam's easy smile was visible. Then he turned and slipped into a cave with the pack, and there was only the Martian's silent grip on the boy's shoulder and the sound of the jets as they sped off across the wastelands.

The warmth of his hands had softened the purple wax, and he sat molding it idly, while his eyes remained unfocused on the shelf before him. Now Earth was faint in the distance, with Mars looming up large and red before them, but he was less certain than before of what awaited him there. Sanctuary or slavery—he could not tell. Somewhere within the notes before him must lie the answer; but his mind went on pacing an endless circle, unable to break from the ruts it had worn, and the key eluded him.

When he began his manuscript a week before, it had seemed so simple, and the ink and candle were still there to remind him of the plan. Among men, it might have worked. But even human motives were uncertain, and these strange men from Mars were of another race. He had mixed with them, supped with their quiet commander, and listened to the tales of Mars that Jaluir told so well. But he did not know them; nor could he hope to before his children were old enough to curse or bless him for the outcome; and that would be too late. With a sudden sweep of his arm, he knocked the things from the shelf into a trash container, and swung around—just in time to see one of the side doors swing open quietly, and an old and familiar figure slip from behind it.

"Gram!"

"Naturally. Who else would spend twelve days watching you through a one-way mirror to see whether she had a fool for a grandson?" But the strain in her voice ruined the attempt at humor, and she gave it up. "I found the candle in your -bag, Omega, and I knew you'd find other ways if I destroyed it. So I made an agreement with Jaluir and my stuff was on the plane when you awoke.... And yet, at the end, I wouldn't have saved you. If there's any difference, I'd rather See my descendants slaves than cowards!"

Omega shook his head dully. "It wasn't suicide, Gram. I thought they might dump me and my notes at once if they were slavers, like the man in your story who tried to cover up and escape punishment for carelessness. Or if they were friends, they'd wait until they read my notes and found out how to revive me."

"Umm. And you'd have no responsibility either way, eh? No, boy. Men could have colonized the planets ten years before the Cataclysm; but they were too busy with their fears. Until the last minute, they were so afraid of war that all they could do was prepare for it, and nothing else. The survivors could have found ways to get to all the valleys and multiply again, but they gave up and sat blubbering about the dirty trick fate played on them. We've been a race of irresponsible, sniveling brats! And now it's time we grew up out of our nightmares and accepted our responsibilities."

Gram shrugged, dismissing the subject, and turned toward the doorway to the hall. "Come on, boy. Jaluir says we're almost there, and we might as well see what it looks like."

But Omega could not dismiss the subject so readily. It was good to have her old familiar strength beside him, but in the final analysis, she could not help. The decision he had been forced to make was his responsibility, and no other could share it. Men had had their faults, and they were great ones. They had come up too fast, and their cleverness had outstripped their wisdom. But no single individual could deny the race one more chance for the good that was in it.

Three centuries of bitter hibernation had burned away some of their childhood, and they could start anew to learn the lessons they had neglected, if they had the courage and were given the chance. The hard radiations that had come, like the rain from heaven on Sodom and Gomorrah, had left gifts to replace the things they burned away, and it could be a great race—almost a new one. Together with another people and another culture to temper its faults and encourage its virtues, it could develop beyond the dreams of all the poetic prophecies.

But would it happen that way, or would men become only the cunning vassals of an alien lord?

"I am Alpha and Omega—the Beginning and the End," Gram quoted softly, as if reading his mind. But the words that should have been encouraging were grim and foreboding. For she had named him Omega, and he was the last of the Earth race. But there was no one to call him Alpha or to promise that he was the beginning of a new race, no longer Earth-bound.

Now they reached the end of the passage, and already the red disc of Mars was pushing back the cold and the darkness of space before them. Omega sighed gently. He could only pray that it was an omen of the future—and wonder.

Perhaps he would never know.