Help via Ko-Fi

HE SAT ALONE at his table, alone and lonely, and his thoughts and memories drifted, drifted, long ago and far away. His lips twisted in a wry grin as he lifted his goblet of wine. The touch of the vessel was cold to the skin of his fingers—and yet, he noted almost unconsciously, there were no beads of condensation upon the smooth surface of the glass. It offended his sense of the fitness of things. This minor irritation sewed to drag his mind away from the irrevocable past, back to the things in the here and now.

He looked around him, trying to find something of glamor in his surroundings, something of interest, something to shake him out of the black mood into which he had fallen. But this was, he thought, the drabbest world to which he had ever come in all his long career as an interstellar navigator. The drabbest world, and the drabbest people. Outside—the mud, and the low, unlovely buildings, and the eternal mists that forever drenched this small, unimportant planet and forever hid from view its dim, ruddy sun. And inside—a reaction from the all-pervading humidity.

The Martian Room they called it. this place in which he was spending this evening of his shore leave. The Martian Room—and in all probability he, alone of all those present, was the only one who had ever visited that planet. But the name Mars was a part of the language of Man no matter where he might be, no matter upon which of the Man-colonized worlds in even the remotest sectors of the Galaxy he might be living. For Mars had been the first world other than his own to hear the thunder of his rockets, had been the first world outside of Earth on which he had lived, and died—and been born. Tenacious is the memory of the race, and long the memory of those early struggles before ever the interstellar drive had been conceived. And so it is that in the language of Man, anywhere, the word Mars has become synonymous with dryness.

Save for the fact that he would have required neither furs nor respirator, a Martian colonist could have found no fault with this Martian Room. The air was dry, dry, with an aridity that tickled the skin and rasped the throat. The walls were cunning three dimensional murals of desert, and flimsy, attenuated cacti, and low red sandstone cliffs. Overhead a white, shrunken Sun, together with a few of the brighter stars, blazed in an almost indigo sky.

And the music was dry, arid, a dead rustle of strings and a brittle rattling of drums. The dancer on the little stage had consummate skill, had grace of a sort. But she was—or so thought Pierre Leclerc—no more than a sere, withered leaf drifting aimlessly before the wind, before the Autumn wind, down-whirling into drab and dusty oblivion.

Leclerc shuddered, looked away from the stage. He thought almost longingly of his cosy cabin aboard Pegasus, of the warm wardroom, of the pleasant company of his shipmates who had been too lazy, or too wise, to brave the damp misery of the night for the sake of such dubious, overpriced pleasures as this unimportant city of an unimportant planet had to offer. Leclerc sipped his wine, shrugged his shoulders almost imperceptibly. He knew that the mood which was robbing his evening of enjoyment would have done so anywhere, in almost any company.

And there was no company here that would, or could, interest "him. His uniform—that of an offices of one of the rare interstellar ships—had attracted attention, would have served as sufficient introduction at any of the other tables. But he had already rejected overtures of friendship, had refused invitations to join parties. The men in the place were a pallid, bloodless lot, withered almost, deadly drab. They must, thought Leclerc, smiling faintly at the conceit, breathe through silica gel filters....

The women would have been—possible. But there was something blatant about them, some hint of a desperate hunger, that repelled him. He was very much of the cat this night-Kipling's cat that walked by its wild lone through the wild, wet woods. He sat by himself, small, dark and self-sufficient, cloaked with an arrogance, a prickly inviolability, that hid a nameless, indefinable need.

LECLERC looked away from the stage, looked towards the door. Something, not quite presentiment, not quite hope, had told him that, just possibly, somebody of importance might he coming in. He distrusted the extrasensory warning, sneered at himself for heeding it, yet looked. And the attendant at the door, uniformed in a flimsy imitation of Martian furs and breathing mask, flung it open.

The woman entered first, and, a pace or so behind her, the two men. She was tall, this woman, and silver-blonde, and she carried herself like a queen. The face was too strong for conventional prettiness, and the mouth too wide, the cheekbones too prominent. The skin of her shoulders was in dazzling, creamy contrast to the black gown that did little to hide the well rounded, graceful strength of her figure.

The two men, also, were in black, but their clothing, although absolutely plain, had all the severity of a uniform. And they were armed; from belted holsters protruded the butts of some kind of hand weapon. They walked warily, but with something of the arrogance of the professional bully. Their pale eyes shifted continually in their pale, hard faces and their hands never strayed far from the pistol grips of their weapons.

An obsequious waiter fluttered before the woman, led her to a vacant table not far from Leclere's. She said. "Yes, this will do," and sank into the chair that had been pulled out for her. Her voice was cold, and clear, and gave the impression of perfect control. The two men—bodyguards?—took stations behind her chair. One of them glared at Leclerc, who realized that he must have been taking an unmannerly interest.

But he wasn't the only one. The music was still playing, the dancer was still jerkily posturing on the little stage, but all the little hack-ground noises of the place, the tinkle of glasses, the low murmur of conversation, the occasional shuffle of feet, had died. There was a tension in the air, a hushed expectancy, and....

The darkness came with the impact of a physical blow. It came with the vicious crackle of hand weapons, was broken, briefly and terrifyingly, by livid stabs and bursts of flame. There was the crashing of overturned tables and chairs, there were shouts and screams. Somebody was trapped among the percussion instruments of the orchestra, and the wild clashing of cymbals matched and augmented the growing panic.

There was the smell of ozone.

There was the smell of burning.

And there was another smell, dank, dead yet alive, sickly sweet.

Somebody found the light switch. The glare of the concealed lights, of the imitation Sun in the high ceiling, was dazzling, painful. It showed confusion, terror, smashed glassware, overturned furniture, frightened people cowering behind the pitifully inadequate cover of chairs and tables. It showed charred, still smouldering scars on floor and walls and ceiling.

Leclerc got unsteadily to his feet. The shooting seemed to be over—and, it seemed, those who had been doing the shooting would never shoot again. The two men in black were sprawled upon the floor, motionless. Their still-smoking blasters were grasped in their hands, but those hands looked, somehow, very dead. Leclerc was curious. And he wondered, too, where the woman was. She Thad not looked the type to bolt for cover as soon as trouble started. And she had not looked the type to desert her friends, or servants, whatever they had been. He went down on his knees beside the nearest of the two bodyguards, turned the body over from a prone to a supine position. It was limp in his hands, cold. The face was unmarked, but the man had died in a spasm of pain and fear that had contorted the features into a terrifying mask.

The spaceman shuddered, turned away from the unpleasant sight. He found himself looking at the polished surface of the table at which the woman had been sitting. It was misted faintly with some dampness that was fast vanishing' in the dry air. And scrawled in the mistiness were words, fading fast, but still barely legible.

"Follow," he read. "Mount Tannenburg...."

And that was all.

And then the police arrived and took charge.

LECLERC stood in the muddy road outside Police Headquarters. It was dark, and the street lamps were mere, diffuse blurs of light, confusing rather than aiding vision. The air was full of the not unmusical sound of water trickling from roofs and walls, along the deep gutters on either side of the roadway. A helicopter threshed overhead, flying low, audible but invisible.

The navigator thought of walking to the nearest automatic beacon and calling an air taxi to take him back to the spaceport, to his ship, but it was only a half-hearted desire and it took no great effort of will for him to overcome it.

His mood, in the main, was one of indignation. He had been ready, as a matter of course, to help the local police force in their investigation of the murders and the kidnaping, but he had first been treated as a suspect and then snubbed, insulted.

So, he thought bitterly, I am to mind my own business. I am to go back to my ship and stay there. I am to take orders from a fat, hick policeman.... He grinned. If he'd had the manners to provide me with transport back to the ship I might have gone.... Now....

His grin faded. What, he wondered, was he to do? What could he do?

A figure loomed out of the fog, stopped before him. From beneath a weatherproof cowl peered a woman's face. The woman said, "It is you. The little of?cer from the interstellar ship. I hoped I would find you here."

Leclerc bowed.

"You have found me, Mademoiselle," he agreed amiably. "What now?"

"Just this. What did Alina write on the table?"

"I would suggest that you call in there," he gestured towards the dimly lighted doorway from which he had come, "to enquire."

"You know, or should know, how much use that would be. But others in the Martian Room saw writing on that table, although you were the only one close enough to read it before it faded. They saw you read it. What was it?"

Leclerc countered with another question.

"Have you a Spurling?" he asked. "Or any kind of flying machine, with maps and instruments? It is too late to think of hiring one at this time of night, even if I had the necessary money on me for the deposit...."

"You didn't answer my question."

"Lend me something that flies, and I will."

The woman smiled. In the, dim light Leclerc saw that it was a hard smile, and reckless, yet not unattractive. And her voice, when she replied, had softened. She said:

"I can see that you want to help Alina. Very well, you shall. But you must let me know what it was that she wrote."

"I will, when I'm sure that you're on the same side as I, as she. I feel that the message that she left was for me, and that I should be letting her down if I passed it on to the wrong people. I feel, somehow, that I have done so already. Those policemen—I did not trust them...."

"How right you were. But—what was the message?"

"I told you my terms."

"Very well."

She raised her right hand. Leclerc, fearing a weapon, jumped back, but it was only a small silver whistle that she held, that she brought to her lips. Hardly had its thin, sweet blast sounded than a. dozen forms materialized out of the mist, rushed in upon him from all sides. He tried to fight, but when his first blow landed he automatically checked himself. His reason told him that this was one of the occasions when it would be in order to strike a woman, but by the time that his natural chivalry saw sense it was too late for him to do anything about it. His captors, all women, hustled him away from the dangerous vicinity of Police Headquarters, down a side turning. There was something standing there, something huge and dim with great, spreading vanes. He was pushed into the cabin, shoved on to a seat with three of the women piled on top of him. Under its whirling vanes the 'copter lifted.

"All right, girls," said the pilot, "let him up now. But keep him covered."

Leclerc, disheveled and embarrassed, levered himself to a sitting position. He looked into the pilot's cabin, saw by the dim light from instruments and radar screen that the woman who had met him outside Police Headquarters was at the controls. Her face was serious, grim. She turned to face him and said, "Pm sorry, but there's no time to lose. Really, there's not. You must believe me."

"Where are you going now?"

"To the airport. I—we—have a Spurling there. After that, you give the orders."

"Mount Tannenburg," said Leclerc suddenly.

"All of five thousand miles," said the woman. "We must hurry." Then, "She should have told us, but she liked playing a lone hand. And she should have known that those two pet gorillas of hers were no protection."

THERE was surprisingly little delay at the airport. There were, of course, the inevitable forms to fill in, the inevitable questions to answer. But the sleepy officials on duty seemed to see nothing strange in a visiting spaceman being dragged off on an aerial sightseeing trip by his hostesses. Nor, in fact, was there. Leclere had known parties with much wilder aftermaths.

The Spurling rose vertically on its turret drive, then leveled off. The lights below them faded fast into the mists. There was mist above them, all around them. The woman—the boss woman was how Leclerc was thinking of her—busied herself at the controls, setting the course for Mount Tannenburg. Then, with the automatic pilot functioning sweetly, she came aft into the main cabin. She said, "My name is Marilyn Hall."

"And mine," said Leclerc, "is Leclerc, Pierre Leclerc...." He slightly accented the given name.

"These five others, Leclerc," said Marilyn, "are Peters, Magrath, Fantozzi, Andrevitch and Connor...."

The spaceman bowed to the women, thinking that Marilyn Hall might have told him their names more fully. Not that it mattered. At a time like this social niceties were unimportant. He concentrated his attention on Marilyn Hall, rather liking what he saw. She was a redhead, with good teeth, an almost translucent skin and a sprinkling of freckles. Her figure was good, and her dress was not trying very hard to conceal the fact.

He said, "Now, what cooks?"

"It's not too long a story, Leclerc, and we'll have time to tell it properly. These ladies here, and myself, and, of course, Alina Rae, are members of a more or less secret society. Alina was our president. We haven't bothered with any fancy names. We've had our passwords, of course, we've had to have them. We've had to work underground. And the only men who have, officially, known of our existence have been those two bodyguards of Alina's.

"But I may as well start at the beginning. This world, as you probably know, has been colonized for about two hundred years. When we came here it was, to all intents and purposes, just a dead ball of inorganic matter revolving around its primary. And yet conditions were suitable for life as we l-mow it. So plant and animal life were imported together with the first "human colonists.

"It isn't—wasn't—a bad world. You, I know, wouldn't think much of it, ever. But it's what we're used to. We were happy here. Until...."

HER face clouded. Leclerc watched her hands, her fists clenching and unclenching. He wondered what it was that she hated so. The viciousness in her last few sentences had rather shocked him.

"I was to be married," she said. "Oh, he was nothing wonderful. Just a Junior Meteorologist in the Weather Bureau. But we were rather badly in love. You know what it's like, or don't you? You make plans for the future, either absurdly ambitious ones or very sensible, strictly down-to-earth ones. But, whichever way. it's fun. And you get to the stage where conversation isn't really necessary and some kind of limited telepathy comes into operation, and it's all a matter of feeling rather than speaking and hearing....

"Then, quite suddenly, he changed. It was hard to define, that change, but that beautiful sense of oneness was gone. And I sensed that he was giving me his time, his precious time, more out of loyalty than because of love. He just wasn't interested any longer. And yet, try as I might, I couldn't discover any rival. Not any human rival.

"I suppose that between me and-whatever it was he must have been in a little, private hell of his own. And perhaps I helped to stoke the fires up a little. Anyhow, one fine morning he stepped over the parapet of the Met. Bureau observation tower, and that was that.

"I—oh, skip it. It doesn't matter. But I began to find that I wasn't the only one who'd been through that particular mill. There's Alina Rae—her husband's still alive, still around, but he wants nothing of "her. There are our friends here, and all the other women, some in our organization, some not. But we—those of us who organized—have been investigating. And we've found.... We've found.... How can I tell you? You'll think us mad.

"Leclerc, you've traveled. You've been everywhere. Can there be such a thing as an intelligent gas—and could it take the form of a woman? A desirable woman?"

"I don't know. I've never heard of it, but that need not mean that there's no such thing. There are the gaseous entities of Fomalhaut VIII, and they have sexes, of a sort. But it seems to be a matter of electrical attraction and repulsion so far as the scientists can make out. Some of the entities carry a negative charge, and some a positive. There's some kind of union, with thunder and lightning—oh, it's all very much according to the handbooks of physics. But it seems to work at least as well as our way of doing things does."

"So it is—possible. Now, this is what we know. One of our members walked out on her husband. She walked out, but she left something behind in the apartment. A concealed camera, set to start up as soon as her husband came in that night. The film, at first, was boring, just a man alone in the house, doing all the silly things that men do when they're alone. And then he did something exceptionally silly. He opened the window, sat down by the open window in his easy chair.

"The fog came in, of course, and something more than the fog. It was a dim, shimmering shape—it could have been roughly human in form, but that isn't important. It seemed, according to the film, to have its own luminosity. But I wish that we could have seen it as he seemed to be seeing it. I wish that any of us could bring such a look to a man's face. It settled around him, that cloud of gas or whatever it was, as he sat in his chair. And that was all there was to it. After a while it went, and left him sleeping.

"That was just the beginning. But, with that as a guide, we found out that these... mist people, or whatever they are, were responsible for all of our miseries. Once a man has known them he forgets us. No, not for-gets, perhaps, but his attitude is-how shall I put it?—one of contemptuous toleration. Nothing that we can do—and you should know how much a woman can do—will ever change it. And even when the men realize their... guilt, the power of these living mists is enough to stifle any impulse they may have towards faithfulness or decency.

"Well, we worked. It was duh work, checking and rechecking, following every conceivable lead. We had to find out where these things came from. And we 'had, too, to maintain secrecy, for we could no longer trust any of the men of this world.

"You haven't been here long enough to feel the dreadful atmosphere of sex antagonism, of fear and hostility, yet I assure you that it is very real. It is a poison that is making our lives a misery. It is a poison that will mean the end of the race on this planet and on other worlds if it spreads. You haven't been infected yet. You, with your experience, might be able to help us...."

"I will," promised Leclerc. "To the best of my ability. But your leader, Alina? What had she found?"

"We know now. She had discovered where these...things come from. And that knowledge must be important, otherwise she would never have been taken as she was. There had been attempts before at killing her, but they had been made by men, ii you could call them men, by poor crazed creatures completely dominated by the evil thing from Tannenburg. Two of them we handed over to the authorities, and we don't know what happened to them. The third one we questioned ourselves. He was stubborn. And he... died..."

Leclere shivered a little. He felt that this was a war in which any person of sense would remain neutral. He knew women — and; knowing them, was inclined, in his heart of hearts, to fear them. The old poet who had made the crack about the female of the species being deadlier than the male had been right.

FORWARD, in the pilot's cabin, a buzzer started to sound. Marilyn Hall stiffened abruptly, then hurried to her controls. Leclerc went with her. One radar screen showed the territory over which they were flying, lakes and forests and, at wide intervals, the geometric regularities of towns. Other screens covered the ship's surroundings in the vertical plane. And it was on one of these screens that a speck of light was steadily expanding.

"Right astern," whispered the girl. "Fifty miles and coming up fast!"

"Can we get any more speed out of this crate?" asked Leclerc.

"No. And that'll be a police ship after us, and nothing on this world can outrun them...."

The wail of a siren burst from the Spurling's receiver, swelled, filled the cabin with panic inducing waves of sound. It ceased abruptly, and then a clipped, official sounding voice said, "Calling ship ZX509. Calling ship ZX509. Heave to. Heave to at once. Marilyn Hall and Pierre Leclerc, Navigator of the interstellar ship Pegasus, wanted for questioning!"

Leclerc went to the microphone. He said slowly, "Leclerc here. I question your jurisdiction over an Offices of the Federation...."

The speaker laughed nastily. Leclerc could picture the fat police official with whom he had already had dealings chuckling over his microphone. The tinny voice said, "I pack my jurisdiction in six launching tubes. We'll stand for no nonsense. Are you heaving to?"

"No!" declared Leclerc. Then, over his shoulder to the girl, "How far?"

"Thirty miles. Still outside the range of their weapons."

"And about nine hours flying time still to Tannenburg?"

"Correct."

"So...."

"So we have no intention of being blasted out of the sky, Leclerc, but we have every intention of getting to Tannenburg. Better hold on. I'm going upstairs!"

The man staggered as the Spurling's nose lifted sharply. He clutched the back of the pilot's seat, yet still had difficulty in maintaining his balance. Then, with dazzling abruptness, it was light. The ship had burst from the eternal mists, into the thin air above the everlasting overcast. Astern of them the ruddy sun was lifting over a vast, unbroken sea of red-tinged cloud. He looked aft. A long way away, still slightly below them, was something from which the sun's almost level rays were reflected in silver fire.

Still the Spurling climbed. And it seemed to Leclerc that the police ship was lagging, was losing altitude. It puzzled him.

Marilyn Hall, sensing his bewilderment, laughed. "This ship," she said, "belongs to Fantozzi here. Her husband is rich—too much money. And, frankly, our Lisa is a little bit of a snob. No locally made plane was good enough for her. She had to have an imported model. And the most expensive imported models are those from Castor IV. What do you know of Castor IV?"

Leclerc thought, hard. He tried to remember his one visit to that world, many years ago. He succeeded in recalling to his mind's eye a vision of barren, desolate rocks, relieved here and there by the glittering, crystalline domes of the human cities. He saw the black sky, the intolerably bright sun, the unwinking stars. He said, slowly and doubtfully, "No surface atmosphere... no use for regular planes...."

"And rocket drive for above-surface transport. The Castorians have modified the hull design of their export model Spurlings, but not the drive. Our Police Department sticks to locally manufactured ships and ram jets. Given an atmosphere in which to work their athodyds are fast, fast. But we have the heels of them now."

"They've given up," called one of the women.

"No," said Marilyn. "They'll be waiting for us at Mount Tannenburg."

THEY were waiting at Mount Tannenburg. The police ship that had chased them was there, and half a dozen others. One hovered on its turret drive directly above the twenty thousand foot peak, the others maintained a constant patrol over the surrounding terrain. Marilyn Hall picked them up on her screens when she was still outside the maximum range of any of their weapons. She sat over her controls, frowning.

Leclerc, in the co-pilot's chair, looked at her worried face, asked himself what she was going to do, what she could do. And it wasn't as though they knew where to go, what to look for. A message scrawled on a misted table top carried compulsion and conviction when it was first read, but it had told almost nothing.

This Mount Tannenburg was too big, the area covered by it far too vast. The very peak, perhaps, was what had been meant? But this much was certain, there could be no false choices. Once landing had been effected the police ships would be down on them like starving vultures on carrion. Provided, that is, that they weren't shot to pieces on their way to a landing....

Leclerc stared at the radar screen covering the surface below them. He noticed that one little spot on the western slopes of the mountain glowed more brightly than anything around it, stood out like a spark of pallid fire in the green-glowing fluorescence. He said, a little doubtfully, "Metal...."

"So what?" snapped the woman.

"I do not know," said Leclerc slowly, "if the famous female intuition is working or not, but mine is. It seems to me that one would hardly find such a large concentration of pure metal in nature. Its existence bespeaks the artifact, and an artifact means intelligent beings. These shimmering ghosts of yours are, one supposes, intelligent in their way. We will look for them there."

"Are you sure, Leclerc?"

"No. But I am sure that by hanging here we're becoming a temptation to anybody with a large stock of guided missiles at his disposal. Take her down. But fast. Then...."

"All right. But I'm not landing her. We'll tumble out as fast as we can and then one of you, you'll do, Fantozzi, she's your ship, take her and carry on down the mountain, as though you're looking for something. And once the shooting starts getting serious, ditch her and get the hell out!"

The Spurling's nose dipped. The screaming jets in their turret turned through an arc of ninety degrees, the glimmering speck shifted from the horizontal screen to the one covering the forward vertical plane. The cloud surface came up to meet them like a solid wall—and the sun went out like a snuffed candle as they plunged into the mists.

The cabin, which had been almost freezing, became uncomfortably warm. There was the thin, high whistle of tortured atmosphere screaming past and over burnished hull and polished wing surfaces; And there was a great flare in the fog, and a deafening concussion, as the first of the police rockets burst below and to port of them.

By a miracle no damage was done. Down they plunged, and down, pressed back in their seats against the force of gravity. Then Marilyn cut the drive, brought the jets round in their turret to check the mad descent. They blasted out again, and the shock burst safety straps and sent cabin furniture crashing away from its fastenings. The ship leveled 0E, hovering very perilously on her flaming jets.

Marilyn Hall jumped up from the pilot's chair, ran to the door. Leclerc, following, saw the woman called Lisa Fantozzi hastily taking her leader's place.

He jumped, fell to a rough sloping surface, rolled until he was brought up short by some kind of prickly bush. He heard the noise of the jets rise in pitch to an angry scream that sounded almost like that of a living thing, looked around in time to see their ruddy flare fast fading into the fog. There was a muffled explosion in the direction in which the Spurling had vanished, but the noise of her drive was not cut short, diminished slowly with increasing distance.

"Leclerc!" somebody was calling. "Leclerc!"

"Here!" he shouted. "Here, Marilyn!"

"We'll come to you. Are you all here?"

One by one, the girls called their names.

"Where's Helen?"

. There was a short silence. then somebody said, "I...I think she fell under the jets...."

Leclerc felt more than a little sick, but pulled himself together. This was no time for sentimentality. If women chose to play a dangerous game....

MARILYN HALL loomed out of the fog, her arms outstretched. He took one of her hands. It was warm, and firm, an anchor to reality. Then two more women appeared, one of them limping badly. "Janet!" called Marilyn sharply. "Where are you? We're waiting!"

The reply drifted out of the gray formlessness around them, thin, frightened.

"I can't—move—The mists—stopping me...."

Leclerc swore. He started to run in the direction of the voice, dragging Marilyn with him. He tripped and stumbled on the uneven ground but somehow kept his feet.

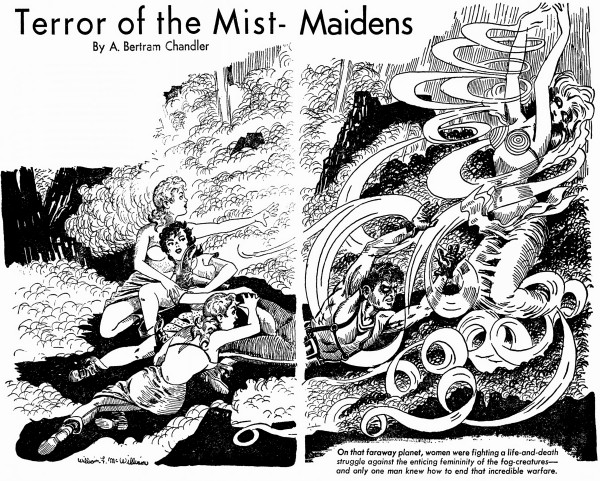

There were no words now coming out of the fog as a guide, no articulate words, just a high, dreadfully thin whimpering. And then he saw the girl. She was standing erect, trying to ward something off with ineffectual hands, and around her swirled a shimmering, silvery vapor. Formless it was, amorphous, yet suggestive in its convolutions, hinting at impossibly perfect curves....

And he felt sudden desire, hot, aching desire—and he felt too that the air was charged with hate, the dreadful, implacable hate of sexual rivalry. And the knowledge of hatred slipped into the back of his mind, and there was only naked desire....

Almost he forgot that here was a woman, one of his own species, in some unspeakably horrible peril. Almost....But with an effort that left him weak and shaken he fought down the imaginings that had come all unbidden to his mind, fought down the urges that strove to inhibit the action his cold intellect demanded.

But he was too late. The solid, flesh and blood woman glimmered and faded, glimmered and faded, and she was gone, and he never knew if the silvery tinkling of laughter came from inside or outside his own brain, the laughter, and the sweet, high woman's voice saying, "She is one of us, now.... And you—will be ours."

And desire came again, and in the shimmering mist, clothed in shimmering mist, was the woman Alina, as he had seen her before, as he had seen her on the night of her vanishing, the same, yet not the same. Her arms were outstretched, and her lips were slightly parted, and "her smile could have been sad, but it was sweet, sweet....And there was fulfilment there, and peace, and all that a man wants and all that can never be given in its entirety by any living woman....

He started forward. He pushed, without comprehension, at the barrier that was holding him from the consummation of his desires. He felt a mouth on his, warm, urgent. He felt a firm body against his own. But the kiss was not what he wanted, not that kiss. He fought against it. But this strange desire was even stronger than his own desire, and it was familiar, and against his will, mind and body, he started to slip down what was, to him, a well-worn path.

And the shimmering mist was just—a strange, shimmering mist, and he was looking into the eyes of Marilyn Hall who was standing pressed against him, her arms around him, and on either side he was encircled by the arms of the other two women.

"A man," said Marilyn bitterly. "I thought that you...." She left the sentence unfinished....

The mists swirled and advanced, hemming them in.

"Fight," muttered the woman. "Fight, damn you! The three of us together might hold it off. And you, Leclerc, no more treachery!"

Again the air crackled with hostility, with bitter, naked hate. The tension rose to a pitch so unbearable that Leclerc wanted only to get away, to run somewhere and hide, to leave these rival manifestations of the female principle to fight it out without his aid or intervention, either one way or the other.

His reason told him that the human, flesh and blood women were right, that they were all the things for which Man has worked and fought and died throughout the long, long ages of his history, home and family and continuity.... And, he couldn't help thinking, his chains.

But they stumbled on, and before them, through the fog, loomed a high wall of metal. It was a ship, he realized dimly, but her plates were crumpled and torn, the double hull pierced in a score of places by the rocks on to which she had crashed. And she was old, old, and must have been here since before the first colonization.

Interest conquered emotion and he raised his eyes to read the worn, tarnished letters of the name, but this, Helen, told him nothing except that she was from long, long before his time, from the days when those who christened ships had drawn heavily upon Greek mythology.

"It is in here," said Marilyn.

"What is?" asked the man.

"I don't... know. But I feel, somehow, that the answer is here.... And keep close to him, you two. Don't let him away! And keep on fighting!"

THICK and thicker swirled the mists, solid almost, yet always receding before the implacable hatred of the three slowly advancing women. Leclerc deliberately shut his eyes, and the images, the shapes of aching, unfulfilled desire, were gone, but in his ears still sounded the voices, and every word was a caress and a promise, and he hated the women who were holding him captive in the drab, gray world that they alone would rule.

Into the ship they went, stumbling over broken plating, their uncertain way lit by a pocket torch that one of the three had produced. They ignored the tattered, formless heaps that had once been bodies, pressed on through riven bulkheads and over dangerously sharp-edged wreckage. At last they came to the Control Room and could go no further.

There was all manner of debris at their feet, and there was a book, and the torch was shining full upon it. By some freak the lettering on its cover was still legible. "Log of the Interstellar Ship Helen...." read the girl with the torch slowly. "From—from Fomalhaut VIII to Sol III...."

"So!" In spite of himself Leclerc was excited. His intellect was functioning once more, and taking a keen delight in the way that the pieces of the puzzle were falling into place. "You remember, Marilyn, what I told you on the way here? About the gaseous entities of Fomalhaut VIII? I begin to understand!"

The mists swirled about them, viciously hostile, and their hostility was no longer only for the women but also for the man who was now their ally. Leclerc stiffened, joined the driving force of his hate to that of the others, and hated himself for ever having fallen under the unholy spell of these creatures of fog and raw desire. He cried:

"There is more here, in this ship! More, much more, that they do not wish us to find! And we will find it!"

"Where?" gasped Marilyn.

"Try aft, the cargo spaces!"

And they fought their way through the broken ship, meeting hate with hate, weakening all the time before the intensity of the raw emotion that swirled about them, that broke against them like the waves of some incredibly storm-tormented sea.

They were weak when they found the cylinders, weak and streaming with perspiration. They stared at the two cylinders with dim, unseeing eyes. There was something they had to do, and they did not know what it was, and almost they did not care. They sat there, huddled together upon a ruined bale, weakly fighting back the forces that strove to overwhelm them.

But still fighting.

"We," gasped Marilyn, "will keep them off. Somehow. You, Leclerc, see what is to be done...."

Secure, but how long? Within the circle of the arms of the three women Leclerc looked at the seemingly innocent metal containers. One was marked with the symbol of Mars, the symbol that has also a biological significance. The other was marked with the Crux Ansata, for Venus.... And that one was open.

It was Nature herself who had opened it. It was the steady dripping of water through a gap in the torn hull plating, for all of two centuries, that had eroded the tough steel. Leclerc shuddered, picturing the hungry entity—or entities—that had emerged, picturing the nature of that hunger, and the way in which it had been satisfied....

He thought of man-eating tigers back on Earth, and the legend saying that once the carnivores had tasted human meat they would touch no other....

But whatever was in the unbroken cylinder had never tasted human flesh....

He whispered, "You'll have to let me go. I have to break the other cylinder...."

SLOWLY, reluctantly, the women's arms fell from him. He picked up a short bar of metal from among the wreckage, raised it to attack the sealed valve, the valve that he could never open otherwise without the proper tools. And the mists surged in to the attack, and, for him, they had abandoned the weapon of hate, and it was the woman Alina who was standing before him, and her eyes were pleading and sorrowful, and her smile was tremulous....

"Don't," she was saying. "It will be murder and worse.... And I am human.... I was human, and now I can give you more than ever woman could...." Her voice trailed off.

He hated the three who still sat on me ruined bale-the three coarse, silly women with their ridiculously strained faces, their evil desire to kill something so much finer than themselves. He knew that there was only one thing to do. He raised the bar again, but this time it was not the gas cylinder that he was going to attack.

Unafraid, even smiling, Marilyn got to her feet. Before he could bring the bar crashing down upon her coppery hair her arms were around him. "My dear," she said, "this is reality, here in my arms...." And it was reality, of a sort, and he despised himself for accepting it as such even while all his body recognized and acknowledged the urgency of hers.

"Take the bar," he gasped, "smash the cylinder!"

"No. You must, my darling. You must!"

And the naked triumph in that last sentence was shocking, obscene.

With a strangled sob Leclerc pushed himself out of Marilyn's arms. The glimmering wraith that was Alina stood before the cylinder, all sweet allure, all that any woman could ever be to any man—and more. But the bar drove down through the living mist, and with the first blow the valve cracked open. With explosive violence what was inside rushed out a shimmering vapor, a cloud of glittering particles, dreadfully alive and urgent.

And of that union Leclerc remembers little, neither Leclerc nor any of the three human women. There was lightning that flared and crackled all around them, there was the thunder that brought the searching police ships down upon them at last. It was a miracle that they survived. but survive they did, seared and shaken in the fused and twisted wreckage of the ruined ship.

It was Marilyn Hall who went to meet the policemen.

She held herself erect, arrogantly. stood on the hillside and let the men come to her. They stumbled up over the rough ground, through the fog that no longer swirled, living and shimmering, that was now dead, gray, and utterly formless.

"You are too late!" she cried.

"Too late?" echoed one of the men. "What...?"

"Yes!" she shouted triumphantly, "too late to stop one silly cloud of gas from being annihilated by another, even sillier! Fools!"

Leclerc came out from the wreckage, pushed past the contemptuous. blatantly exultant woman. He grabbed one of the policemen by the arm. He said, "Get us out of here. Get us back to the city. I can't stand any more."

Marilyn came and stood beside him, took his arm possessively. "Yes," she said. "There is no more danger. Take us back."

Nobody questioned her right to give orders. Leclerc felt sorry for the men of this world. For generations they would pay for the wrong that they had done the women, and for generations the women would crack the whip. He was very glad that he did not have to stay here, and hoped with all his heart that he would never come here again.

It was here that he had been faced with the choice between shadow and substance, and—

"Either way," he whispered to himself, "I was doing the wrong thing."

Marilyn dropped his arm, and between them was a taut, injured silence. He knew that once the police plane should have carried them to the city he would never see her again.

And he was not sorry.