Help via Ko-Fi

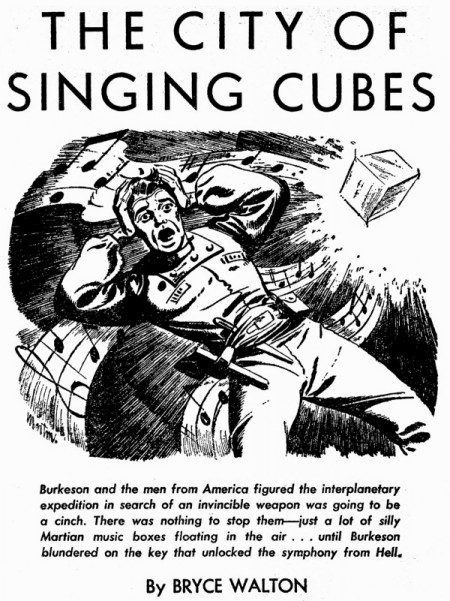

THE CREW was gone. Captain Ballance, and Lt. Dobson, and Clevenger and Ferrell and Hopkins, all of them gone. Burkeson sat in the rockets shadow and thought about them; and, hearing the rapid change in the city's symphonic voice. Burkeson knew that soon he would go. and then the rocket would go. And after that—

His laughter was shrill in the thin Martian night, echoing against the rocket's skin, and drifting off across the red desert. In his laugh was 8 crazy climbing note of lonely fear.

That mounting thunderous destruction in the music of the city—what an awful difference, he thought wildly and stared into the shadows of distant city spires. It's all through the music now, the corruption and hate, and it's growing and growing, and we taught them—

The symphony's theme was changed, forever, to the horror that never existed here before the rocket came. Harmonies and sustained notes in the Minor were creeping in. The sombreness of the key of G, the brutal sinister and gloom dramatic violence of C, and the sad agitation of E.

He wondered how long before it changed enough to be able to destroy him, too, with its hate.

It was funny, he thought, but that first night, when we landed, none of us, except Clevenger, knew why we were here, but they sensed the purpose. And at first, no one knew what to do, and no one was aware of the music. . . . "

FIRST, the necessary routine stuff. The testing of atmosphere, and the observation of surrounding terrain from the safety of the rocket's interior. There was the familiar Canal, the distant city, the barren mountains, dead sea-bottoms. And that was all. No eight-legged beasts or giant birds under the double moons.

Then they got out and stretched and breathed the clean crisp air, and looked at each other as though not quite sure they actually had arrived and were on the Martian desert, or whether they were merely ghosts of an idea.

They were spared the excitement of surprise at finding the canals and the city, for that had been observed and charted through the Palomar eye. Burkeson felt the music at once, but remained silent as he tried to analyze it. The others didn't seem to hear it. His hypersensitive and musically trained inner ear registered the sounds that were apparently inaudible to the others. A delicious alien sensation seemed to swim through him with his throbbing blood.

Captain Ballance, a blond, neatly uniformed giant, stood and looked at the distant spires of the gleaming city.

"The big question is," he said, "—life." And the others were obviously thinking of that too. Burkeson's head was cocked to one side, puzzled wonderment in his eyes. No one noticed his odd reaction. Burkeson was an oddity anyway, a dreamer, an unrealistic sort, except in his specialized field of audio engineering, and electronics.

Ferrell, the atomics man, was sifting sand through his fingers and noticing that it felt much like any other sand would feel anywhere, on Manhattan or Long Beach. Lt. Dobson was breaking out a case of rations for a little celebration, though no one seemed festive. Ferrell walked over beside Burkeson and Ballance. He also looked at the distant city. Its softly shifting pastel harmonies flickered in the moonlight.

"Beautiful," Burkeson whispered.

Ferrell said. "The question is, how alien is life here likely to be?" His small fat body shivered, and he folded his arms. "Maybe we can't get along with 'em. Maybe they'll be super-intelligent, or savages. In either case, maybe they'll be so different, we'll never be able to get anyplace with 'em."

Capt. Ballance's cold hard face turned to the big neutron cannon mounted between the rocket's two skin casings. His voice was grimly final. "We're not worried, Ferrell."

Burkeson said softly. "But where would we want to get with them? That's the thing I want to know. There hasn't been any enthusiasm here like you'd expect on a first flight to Mars. It's all too grim! I want to know what we're doing here?"

"Why do humans do anything?" Ballance said. "Might as well ask that. Why did western culture expand, and murder primitives by the millions just to expand? Who the devil knows? Economics, instinct, geography, a complexity of causes. There may not be any general reason we're on Mars now, except that it's just a way-station to keep on expanding."

Clevenger came up with a bottle of beer in his white hand and a thin smile on his sardonic face. Clevenger, the North American Defense Federation Representative, whose presence lowered Ballance's title of captain to only a name. As a representative of the NADF, Clevenger was part owner of half the world, and his words directly affected the private and general lives of billions.

Clevenger said. "You spoke with broad generality, Captain. Now that we're here, and not just because our aesthetic comrade, Burkeson, has specifically asked for it, I think we should all know why we're here. Get any romantic nonsense out of your heads, men. This is business." He looked at the city. Hungrily, Burkeson thought.

"We're here to see if there's anything we can use," Clevenger said softly. "Especially in the way of—weapons."

BURKESON was sick. For a second, he forgot the strange music from the city. All this planning, and expense, and the dreams man had always had of going to the stars—the great black mystery of space, broken—and for what? A better weapon!

Oh Lord, he thought, what could be more horrible than that, more of an indictment! He noticed that none of the others seemed to care about Clevenger's disclosure. A lifetime of militarized regimentation had dulled their imaginative faculties. This thing was routine to them! It was incredible to Burkeson, sickening.

He said. "It seems very quiet and peaceful, but it isn't. Can any of you hear anything? There's music, very muted and slow and much of it lost to our hearing because of frequency, but it fills the air."

He leaned toward the city. The others stopped whatever they were doing and listened. Perhaps they still didn't notice as strongly as did Burkeson, but as they listened, they began to hear shades of what Burke-son had been hearing.

For awhile no one said anything, then Clevenger smiled thinly and arrogantly, and said:

"Probably got a big hand out to welcome us. Probably terrified at our landing, might even think we're gods or something. I'd suggest that we break out weapons from the arms locker, Captain, and trek over to the city and see what's what. The city actually might support some kind of life that knows we've landed, and are preparing a little surprise welcome for us!"

Burkeson closed his eyes. Oh, Lord. A band! His compatriots didn't understand at all, They haven't any idea what it is, this music, nor what kind of highly evolved aesthetics are necessary to create such glorious sound.

Ballance nodded the necessary orders. Two men remained to guard the rocket. The rest moved on to the city, armed with neutron rifles and revolvers, and one man carrying a compression gun firing atomic warhead shells.

As they approached the city, the music seemed to swell until Burkeson felt that he was breathing it. Ecstasy trembled through him so that he could hardly force himself to walk on toward the heart of the sound.

He knew now that he never really had heard music before, but only the most awkward ignorant primitive attempts to create it. He had a vague and magnificent hint now of what music was.

But—it was too perfect, too big and too beautiful for human senses. He grabbed Ballance's arm so that the captain stopped and consequently the group stopped.

"I don't think we should go any further, Sir."

"What's that, Burkeson?"

"I don't think it's safe. That sound's the result of highly specialized development, Sir. It's a kind of perfection that maybe the rest of you haven't sensed as easily as I have. I'm trained for sound. I've a faint idea what mastery of audio engineering is necessary to produce a symphony like this. It means they're way ahead of us in sonic science, which could mean they're away ahead of us, period. They might be hostile, and unwilling to waste time in getting acquainted. I'd suggest that we wait and try to figure out exactly what we're really up against."

Clevenger laughed. Hatred for him and his egotistical laughter hit Burkeson, hard.

"What kind of so-called logical reasoning is that, Burkeson? If you're afraid, admit it. But we can't afford to. If there's any intelligent life here» we've got to impress them with our lack of fear, our superiority. And we've got to maintain that impression even if we have to put on a demonstration of force!"

Several voices shouted agreement. All the voices joined in with a roar of agreement, except Burkeson. Someone sneered at him.

They walked on toward the city, though more slowly now. The volume of delicate yet voluminous sound swelled. And inside Burkeson the ecstasy grew with it. And also a hint of fear.

DELICATE RIBBONS of blue pastel highway curved into the city. There were no gates, no walls around it. There weren't any cannon on the parapets, nor any sign of armed men on guard. There is just a city, Burkeson thought, and the music.

"No trouble here," Clevenger said triumphantly. "If there are people here, I've an idea they'll be malleable. It's obvious they're not set up for any kind of defense. Probably in some stage of decadence. Civilized and progressive peoples are always set up to defend themselves against any at-tack."

The words grated in Burkeson's mind.

Then they stood in the center of a curving avenue in the moonlight and looked and listened and wondered. Spontaneous unease filtered among them. Ballance stared into the soft architectural beauty of the city, and had his rifle pointing into the purple shadows. Clevenger was analyzing what he could through his eyes alone, ignoring the music which was meaningless to him and the others.

He said. "I don't see any signs of life. just that longhair noise! Maybe there isn't anything alive, and something's been playing this highbrow racket mechanically for centuries!"

Ballance said. "Whoever built this city was advanced all right, like Burkeson said. I hope there isn't any life here. Make it easier for us, I guess, to get what we need and get out."

Clevenger said. "They must have developed some pretty good weapons too. Any highly civilized race has terrific weapons. We'll find such weapons, whether there's any life around or not!"

Something moved past them. It moved noiselessly, gliding over the gently curving walkway and into the purple shadows. Ballance crouched. Every man stood with weapon ready, tensed and waiting. Very coolly, Clevenger said:

"It was a cube, about half my height, wasn't it? It looked like metal or some kind of shiny plastic, same as the buildings. Wait, we won't follow it up yet. Take it easy. If they show us any signs of trouble, blast! Psychologically, we've got to show them their place from the start."

Burkeson gagged. He stared past Clevenger after the disappearing cube. As it moved past, the cube had glowed and pulsed with ever changing monochromatic light harmonies which, Burkeson thought, would correspond to the sound it was giving off in the form of music.

Burkeson knew that part of the great orchestration rising from the city came from this cube. It was an instrument. He felt that it was alive, that it was Martian life. He felt strange because he seemed to know. He didn't see how he could know.

He thought of a cube blasted with neutron rifles, that instrumental perfection exploding, and the coloration fading to corpse gray and freezing there while the vast orchestration over the city lost part of its completeness.

Weapons! Always looking for better and bigger weapons. Clevenger represented North American Defense Federation. The other half of the world, the Asian Defense Union, hadn't been quite fast enough, and NADF was on Mars first. Advanced weapons that would break the balance-of-power deadlock between the defense zones was sought.

Bitter hate hit Burkeson again and again as he listened to the swelling music around him, the peaceful stability of the city. He felt like a beast stalking into a patio, dripping bloody saliva over a garden.

Burkeson had never thoroughly conformed to regimentation. And he had always expressed, in any small individual way he knew, his intense hatred for the prison militarism had made of the world. All-out defensive militarization had made people fit into the machine, regardless of their natural abilities. Burkeson was an audio engineer, an electronics man, and he had been a composer until the big draft. Since then, very little devotion to music. He knew he hadn't been adjusting any too well to his frustrations.

Everyone lived always with but one thought: wait and prepare because someday they'll attack. We must be ready. And the other half of the world lived always with but one thought: wait and prepare because someday they'll attack. We must be ready.

It didn't make any sense of course, Burkeson knew, because someday, no one had any idea when, the delicate balance of fear would topple one way or the other and—poof! But no one ever thought about that much any more.

It was always: invent a weapon a little more horrible and gigantic than they've got, so they'll be afraid to attack us. And so the weapons got bigger and more horrible on both sides. The only thing was, there began to be a limit on what innovations could be dragged up by physicists and biochemists and biologists and the fear-making psychologists. The point was reached Where there was the search for one ?nal weapon, capable of completely wiping out the others, without also destroying the entire earth and everything on it.

So come clear to Mars to find it, Burkeson thought. And he smiled, his mouth stretching taut like fine dark wire. And if we don't find the super super weapon here, go on and on, and explore the stars clear to Centaurus. Find something more super than anyone on Earth can create.

So they looked for the super super weapon.

And the only thing they could find was—music.

THE CUBES seemed to ignore them, or else didn't sense their presence at all. Communication with the cubes was attempted, and abandoned. Everyone but Burkeson decided they weren't alive. But no one paid any attention to Burkeson, for a while. His aesthetic philosophy was too unrealistic and introverted, they thought. But he did know his field very well, sonics. And they finally realized that if anything was to be found out about the city, Burkeson was the only one qualified to do it.

They moved into a large beautifully constructed hall in the heart of the city, with plenty of equipment, setting up headquarters for exploration, for testing or attempting to test the unknown elements of which the city was built. And always trying to figure whether the cubistic things that moved silently over the floors and along the shaded streets were intelligent, whether they were alive, or organic, inorganic, or semi-organic, colloidal. Or what.

They glowed with ever-changing color. And music came out of them, always. For miles around and beyond the city the giant orchestrations could be heard. And in the city itself the sound became something taken for granted and almost unnoticed. Except for Burkeson. He sat hour upon hour, eyes closed, listening, his mind reeling in clouds of magnificent sound.

Ballance called him in the next afternoon. And Clevenger was there to ask questions and demand answers. Clevenger sat with his feet propped up on a glowing cube that was conveniently not moving at the moment. As Burkeson came in and saluted, Clevenger deliberately ground his cigarette out on the side of the cube. A piercing pain hit Burkeson as though he had felt the burning coals. The cube's coloration flickered with momentary ugliness.

Burkeson gasped. He leaned over and almost grabbed Clevenger's arm. Clevenger grinned.

"It's alive!" Burkeson whispered. "I've told all of you that. These cubes make the music we hear. This is their city."

Ballance said. "That isn't the question, Burkeson."

Clevenger said. "We need your advice. Looks as though this city is geared strictly for sound. That's your department. You mentioned that these people—you call them that—are masters of sound. Could you elaborate?"

Ballance said. "You mentioned to Ferrell about communicating with them."

"I don't know," Burkeson said stiffly. "Given time, I think we could. I believe they're of a much higher intelligence than we'll ever be."

Clevenger started, flushed slightly, and his fingers started drumming on the cube. "Matter of opinion of course. I'm a little too proud of being human to admit that. All I want to know is, how do they function? Alive or not, I'm sure no human will ever find any emphatic response to them, whatever they are."

"Maybe not," Burkeson said. "But it seems to me it should be obvious that they're intelligent, that this is their city. I think we could recognize them as being entitled to our respect. They didn't invite us here. This is their planet, their city. They've found a kind of ultimate peace and beauty we'll never be able to find."

Ballance coughed. "We're not interested in sociological problems now, Burkeson. We've taken plenty of photographic reels, and sound tracks. But we've found no machinery, no power plants. No evidence of atomic or electrical power. We believe the cubes contain the secret, but so far we've hesitated about tearing one down to see what makes it tick. You suggested ultrasonics—"

Clevenger leaned toward Burkeson. "I know a little about audio engineering. I know our scientists have been working in that field for years, looking for weapons. Ultrasonics in solids. I believe these cubes are animated machines. My idea is that they're machines that can keep themselves going by hidden sonic power. That they're robotics of some kind, left by a dead civilization. What do you think of that possibility, Burkeson?"

Tear one of them down. Music like this—out of a machine—tear. . . .

Somehow, Burkeson remained calm, and underneath, he wanted to kill. His hand shook, and he felt perspiration crawling down his face.

"I've told you my opinion, Sir. I think they're alive and highly intelligent. And so far above us that they may not even realize yet we're here. They're masters of ultra-and super-sonics. City and individual life here is supported by it. I think they communicate with each other by music, a small part of which is audible to us."

HE GOT UP then and stood so that the cube was between him and Clevenger. The individual instrumental music from the cube seemed to envelope him in a separate cloud of sound.

He said. "They've developed along much different lines than we have. My idea is that now that we've started exploring space, we can't keep on looking down on everything that's different than we are. Maybe these cubes are partly mechanical in structure. This whole city is structured for a vast communal interrelated ultrasonic life. I can explain something about what controlled and focused vibration can do to solids, what ultrasonic potentials are.

"But I'm afraid you would find it rather technical. For example, the acoustic material of this city has been chosen and built so as to make the reverberation time the same for all frequencies, resulting in the loudness of all frequencies decaying at the same rate. The acoustic material shows a variation of absorption coefficients. In other words, they've done what our scientists could scarcely imagine. This city and the cubes are in tune, you might say.

"I think each cube is living and intelligent, and is also a part of a vast ultrasonic social culture, all working in complete vibratory harmony to create and sustain their own existence, to create music that's literally an endless joyous sensual life for them. It's beauty that our senses can't imagine.

"I've gotten an idea of what's been perfected here. These cubes can do almost anything through their control of vibration, that's the way I've got it figured. You know yourselves how we can use it for measuring, detecting flaws, in processing foods, drugs and chemicals, and as a catalyst to speed up chemical reactions. You know about the crystal type of ultrasonic unit that uses electrical energy instead of air as a source of power, and quartz crystals transform electrical energy into mechanical vibrations. Maybe these cubes operate on somewhat the same principle, infinitely complicated. I don't know.

"I know about all that humans have found out so far about ultrasonics. Which is to say, practically nothing. These cubes know everything about it.

"All I say is that I think these cubes are alive, and that they've mastered ultrasonics as well as the secret of living in harmonious beauty. Through extreme specialization, I think they've completely mastered their environment."

Clevenger said. "Very interesting speculation. Except that now we're part of their environment. Say, where does all this humility come from, Burkeson? Don't you like being human?"

Burkeson didn't answer that. He could have. He could have said that during the last few hours, that question had been bothering him. He was uncertain.

Ballance said. "Anything else, Burkeson? About the cubes?"

Burkeson shrugged. "My interest in them is their complete mastery of music. My interest, as you may remember, was composing, before the draft. I can tell you this to illustrate their mastery of music, though this is only a small part.

"For example, to fairly represent even the crudest kind of music, the range of frequencies should be from 40 to 60, to 14,000 or 15,000 cycles. And the acoustic power range above the threshold of hearing should be from 0 to 70 decibels without distortion. Yet these people have gone so far beyond these ranges that my instruments are not worth anything. And yet, I can understand something of these people, and their culture."

"But it's completely alien, isn't it," Clevenger smiled. "And there should be no more hesitation about-tearing these cubes down than in tearing down a highly specialized anthill to study it."

Burkeson felt his hands clench to wet fists. "I'd rather try to work out some means of communicating with them, learn their secrets that way. Maybe by subjective harmonics, and nonlinear response. If you want that explained further—"

"No! Forget explanations now." Clevenger was on his feet. His face was drum tight with anger. "This is your specialty. We have only a few more days here. And regardless of your attitudes, we're going to tear down these cubes, Burkeson! And you're ordered to oversee the job!"

He breathed deeply, then said. "If they've developed this fantastic mastery of ultrasonics that you say they have, then certainly these cubes contain the secret of some kind of ultrasonic weapon. And that would be exactly what we need to finish the Asians. There'd be no defense against ultrasonics. Specific vibration could destroy any defense. Our scientists have been working on ultrasonics. looking for a way to utilize sound waves as a weapon, for a long time. They haven't gotten anyplace. Why is that, Burkeson?"

BURKESON felt nauseous weakness. He leaned against the desk. He put out a hand and touched the cube, and suddenly a strange thrilling strength seemed to flow through him.

He said. "The difficulty is in narrowing the destructive vibration waves down to concentrative focus. Waves have a tendency to spread. If a way could be found to funnel the sound waves into concentrative focus, anything could be shaken to pieces, completely destroyed, by finding specific vibratory rates."

Clevenger said. "And these cubes should have that secret shouldn't they?"

"I don't—know," whispered Burkeson.

"Then," Clevenger said, "I think you'd better start looking into the cubes and finding out. The secret of one of these cubes might very well give us the drop on the Asians, enable us to destroy them all, and all their works. I'm afraid the NADF will hear of your uncooperative attitudes, Burkeson, unless you show a great deal of change."

Clevenger said to Ballanee. "I'd suggest that you put Burkeson in charge, with Ferrell and Hopkins to assist, at once. We'll take several of the cubes back to the ship and tear them down. If the job seems too difficult, and looks like it might take too long, we'll take a cube or two with us back to Earth. Whatever there is to learn is in the cubes anyway."

Burkeson was dismissed. Ferrell was sent to the ship after a small power car to mantle and bring back to the city for hauling cubes. Burkeson went outside into the cool shaded street. And he sat down beside a cube to wait. He sat in the shade cast by the cube, and buried his face in his arms.

Reality seemed slowly to fade. It became as though he were swimming in an endless sea of glorious sound, and that he was Orpheus, or the angel Israfel.

He had felt without knowing how. Now he knew. Their music was language, and he understood its broadest semantic meanings. He had always thought that if man would find a universal language, it would be in the realm of basic, vibratory harmonies that even in their crudest form had such profound and deep effects on the senses.

Chance didn't move Beethoven to select the key of E flat for the Heroic Symphony, Burkeson thought, and that of F for the Pastoral. It was in obedience to that mysterious law which assigns to each key a peculiar aspect, a special color.

There would be slight variations according to temperament and conditioned responses, but basically it was a physical law of general reactions. A certain vibration must inevitably have specific effects on physical structure.

Wrapped in that surrounding symphony of sound, Burkeson began to feel that he was in general contact emotionally with the cubes' mental world. Not with any individual cube, but with the whole interrelated sound structure of each cube and the city itself. And it seemed that as a result, entire emotional messages impinged on his nervous system, flooded his brain with understanding. It was a hind of ultimate method of comprehension, of evaluation, that one could term semantic.

And they were in touch with him, and their music was a language that he felt in great floods of understanding. And they understood his own anguished outpourings of feeling.

He felt the resulting horror as they absorbed his emotions. There was retreat, then mote absorption, then shock, then slow horrified comprehension. Burkeson clutched his head suddenly, as if invisible hands were poised to strike. His body began to shake.

He staggered to his feet, screaming with pain and horror as their emotional reaction poured back upon him. He stood swaying, pressing his temples with shaking hands, his head rocking.

The pain slowly faded. He stood with his eyes closed. And then he felt the change begin in the music of the city. Major chords began to mingle and seek to establish themselves.

The doleful anxiety of A♭. The funereal and mysterious pathos of B♭ crept in, retreated, moved in slowly to remain. G, sombre. C, brutal, sinister. E, sadness and agitation. C. gloomy, dramatic, violent. F—hate, hate, HATE! C and F. Hate, destruction, hate, destruction.

E♭, profound sadness of realization.

Then, C and F. Hate, hate, hate. Destruction.

KILL. KILL.

Burkeson yelled hoarsely. He turned and lurched back through the arched doorway; he screamed at Clevenger. He screamed at Ballance.

THEY straightened up quickly, and Qlevenger licked his lips slowly as he saw Burkeson's twisted face. Burkeson started babbling. He screamed at them, insults and threats, but he wasn't making much sense, Clevenger thought. Ballance looked meaningfully toward the two guards with rifles by the door. They nodded, and their rifles swung around.

"Psycho," Clevenger said.

Ballance's hands fumbled around his desk, came up with a revolver. He pointed it at Burkeson who didn't seem to notice, or care particularly.

"Burkeson!" Ballance shouted crisply. "Snap out of it, man. That's mutiny you're talking! Insubordination! Guards, take him back to the rocket to the Doc, give him a hypo and—"

Burkeson laughed. "Fools, fools!" He laughed until he cried. "Poor proud fools!"

Clevenger waded through a. pile of pneumatic cushions, piles of tape recorders and tape and files. He yelled at Burkeson.

"What happened to you? You go outside, then you come back in a few minutes later, with your top blown. What's eating you, Burkeson?"

Burkeson staggered. The muscles of his face twitched. He opened his eye slowly and there was something leaden and dying in them.

"We're humans," he said, "and we can't help what we are. Maybe we got off on the wrong track somewhere. I don't know. I don't blame you, Clevenger, for being power-mad, and never able to think about anything except how you can destroy half the world and kill off billions of people. . . ."

"Burkeson!"

"No, you're just something that happened, like everything else. I don't blame you, Clevenger. Or you, Ballance. I don't blame anyone. I just feel sorry for everyone now. I'll say goodbye now, because any minute the Cubes are liable to start doing what we've taught them to do. To hate. And—kill." .

"What're you talking about?" Clevenger stepped back. His eyes flick-cred.

Ballance said. "Explain yourself. Or you'll go back to the ship under guard. and you'1l be put in solitary until you get back to Earth for a trial."

Burlrcson shivered. "Maybe it's better this way. We've gotten this far. Maybe we'd go on and on and whereever we'd go, we would always be superior. Top dog." Any race that didn't look like us—they'd be like ants in an ant-hill, like you said, Clevenger. Wherever we'd go, we'd take hatred with us, and suspicion, and contempt, and the ability to conceive and wage mass warfare, total slaughter. And who knows, Clevenger, maybe we're the only race in the Universe who can even think of such a thing. No other animal on Earth ever thought of it. Maybe what the Cubes are doing is all right. I don't know. It's too late now to care."

Burkreson raised a hand and leaned against the wall. His face was drawn tight, and perspiration made a stream down his throat. The two guards shifted uneasily, their rifles trained on his stomach. The weapon in Ballance's hand wasn't steady. He looked at Burkeson.

"All right, I'll tell you," Burkeson whispered. A curious coolness slid along his spine.

"We're all going to die. Maybe if we start right now, we could get out of the city. The Cubes don't understand yet, all of the meaning of what they got out of me. They've learned about hate, and the idea of killing for self protection. They've learned the art of killing to keep from being killed. It may be a little while yet before they're able to convert their faculties to techniques of killing. But there might be a chance. So maybe if we get out of the city fast, we can make it—"

Clevenger smiled thinly. "We don't run from a bunch of cubes, Burkeson. You're crazy, that's the size of it. That sensitive, artistic, mind oi yours has cracked wide open. That music has been too much for you. Go on back—"

"Wait a minute!" Ballance got up. He moved around the desk in quick tense strides. "Maybe Burkeson does know something. These men are under my command, and I'm responsible for their safety. I can't afford to overlook a possibility of danger. After all, Clevenger, we're in alien surroundings. We shouldn't gamble with these men's welfare."

"It's too late," Burkeson whispered harshly. "The game's over."

"What?"

One of the guards covering Burkeson screamed shrilly. He was on his knees screaming. The other guard had disappeared. His rifle lay on the floor. The second guard sprawled out flat, screaming hysterically, pounding his closed hands against the smooth glistening floor.

"He fell apart, all at once, and nothing's left of him. He fell apart, crumbled away in the air. He fell—"

Ballance yelled into his wrist radiolal phone. "Attention! Attention! The Cubes are attacking us. Shoot your way out of the city now! Now! Every Cube is your enemy. Fire full neutron charge into every cube encountered. . . ."

Ballance was still giving out orders, and running toward Burkeson when he crumbled away to drift like dust on the air. The coiled revolver thudded and spun across the floor. And suddenly the revolver also disintegrated completely, leaving no trace.

CLEVENGER was staring at the remaining guard's sprawled body as it was shaken to pieces, vibrated out of existence. The two guards' rifles followed, into the air it seemed, as Clevenger watched.

He moved in short jerky steps toward Burkeson, and he slid the heavy coiled weapon from its case and leveled it. His eyes were dark and hot and saliva quivered on his lower lip.

His whisper was dry. "You told the Cubes! Didn't you? You let them know why we're here! You little sniveling, crawling quisling!"

Burkeson shook his head slowly, sadly. "No. No, they found out from me, but I don't know how. A universality of musical language maybe. Or maybe just a coincidence that the cubes had an emotional evaluation set to music that is somewhat similar to ours. Anyway they found out. Just as I found out things about them.

"Clevenger—they knew only beauty and peace—until now. Maybe they did know other things way back somewhere in their beginning, but it was almost gone as a racial memory until now. We revived it, gave it stark meaning. We've changed the music of their language, Clevenger. Can't you hear the thematic change? Can't you feel it?"

Clevenger's eyes fled wildly around the hall. His skin was gray and his eyes were hot and black. There were two lines, thin ugly lines, crawling down his cheeks to his mouth. He wet his lips carefully, and the coiled revolver shook in his hand.

"They've learned from us," Burke-son whispered, "a new theme. And they might have forgotten the meaning of fear and hate and kill. They knew what we felt. They know that more and more rockets would come, if they let them come. And that more and more hate and contempt would come with the rockets, and finally destruction. So they're stopping us. Now."

Clevenger yelled something. "They're stopping us now, in the only way we can understand."

Clevenger screamed. "We're not finished yet! Maybe they'll get us, but there'll be more rockets all right! Thousands and thousands! Looking for revenge for what the Cubes are and what they've done to us. They'll atom-bomb this city to dust! All right, so the Cubes'll get me! But I'm going to have the satisfaction of getting you, Burkeson, my way. You dirty little quisling!"

Clevenger started to fire the coiled revolver. The revolver and his right arm disappeared. Clevenger stared at the emptiness. His face was a terrible sculpture in wet, shiny putty.

Burkeson gasped. "No! I don't think any more of our rockets will ever land here now, or even get within bombing range of Mars. Not now. The Cubes have mastered ultrasonics and supersonics; they can do things our science won't reach for a million years. They can even induce high frequency focused waves far out in space to disintegrate any approaching rockets. That's what I'm wondering about now, Clevenger:

"What is their limit? What is the range of their ultrasonic power?"

Perhaps, Burkeson thought, Clevenger was wondering about that too when his body crumbled away and drifted across the room in a cloud of dissipating dust.

BURKESON staggered into the Martian afternoon. He walked down the wide beautiful street, alone. He knew he was the only one left alive now. Molecules shattered into invisible forms by tremendous acceleration, by forces no human mind could understand.

A human body changed almost immediately by ultrasonic frequency so high there was no accompanying noise or vibration audible, into particles so small they floated in air, and were of colloidal dimensions.

And he felt the growing momentum of the change in the musical voice of the city.

He walked stiffly, dazed and numb with shock, and with the other feelings, too. Of resignation, and a sense of the incredible beauty around him, not quite drowned yet by hate.

He sat down in the shade cast by the rocket and waited. There was nothing else to do, nothing else he particularly wanted to do. He knew that after a while, the music would alter its theme to such an extent that there would be no longer any sympathy with him. Then they would get him too, as they had the others.

Their hate would rise and rise until he and the ship would become its objects. So Burkeson sat and looked at the distant Martian city spires fingering the moonlight of Phobos. And as he sat and waited, the symphony from the city gradually fell into the sombreness of Flat and Minor keys. It lost slowly and forever its radiance and warm joyousness of B, and the gay brilliance and alertness of D, and the noble elegance and grace of Bl'.

Flats and Minors dominated completely, and the brooding thundering hate rolled through the dark. Sadness and agitation, and doleful anxiety changed to brutal, sinister, funereal and violent hate.

What is the range of their ultrasonic radiative power, Burkeson was thinking. He looked up. He tried to pick out which of the stars in the sky was Earth. But he was no astronomer, and maybe that wouldn't make much difference either.

The Cubes had learned the value of aggression. That complete sudden devastating offense was the only defense. Again he looked at the stars, at a probable Earth, If the Cubes could focus and funnel enough power —that far. If they could, they would not wait for any more rockets to cross that space. . . .

He stood up, and raised his hand. Their theme was altered now. He whispered. "Good-bye, beautiful people."

A few hours before the Cubes night have understood this sentiment. But not now. Burkeson's last sensory impression was of a small lonely chord in the Major key of E, trying to be radiant and warm and joyous, and dying in a rising roar of thundering discordancies.